For two millennia, Euclid’s Elements, the foundational ancient work on geometry by the famed Greek mathematician, was required reading for educated people. (The “classically educated” read them in the original Greek.) The influence of the Elements in philosophy and mathematics cannot be overstated; so inspiring are Euclid’s proofs and axioms that Edna St. Vincent Millay wrote a sonnet in his honor. But over time, Euclid’s principles were streamlined into textbooks, and the Elements was read less and less.

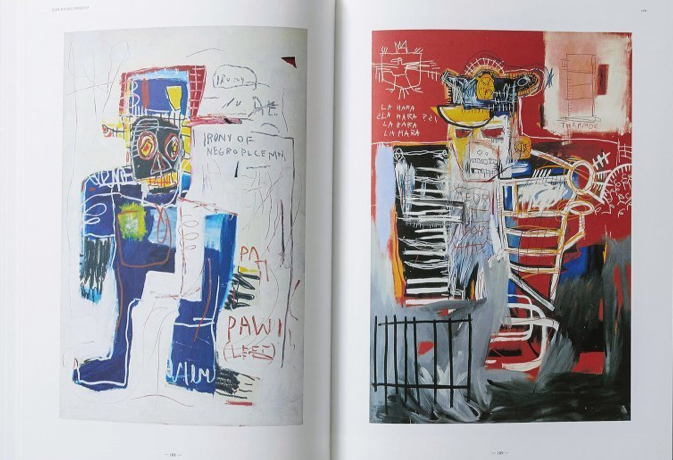

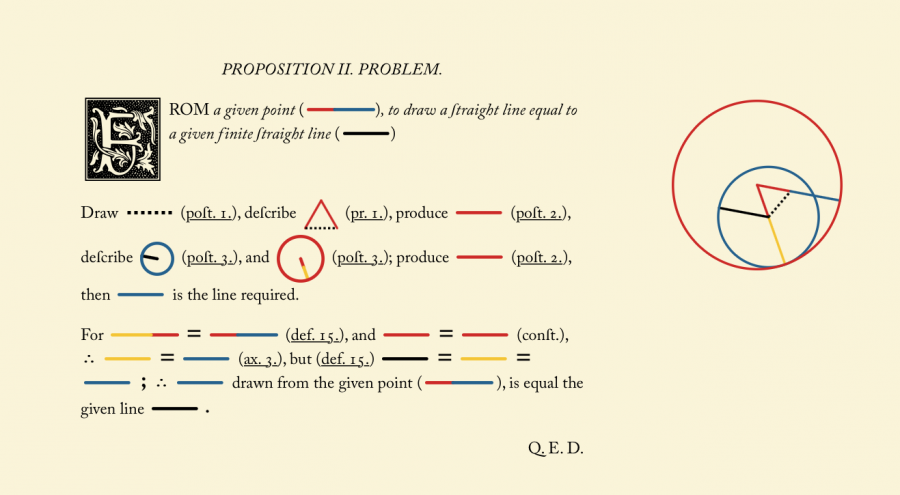

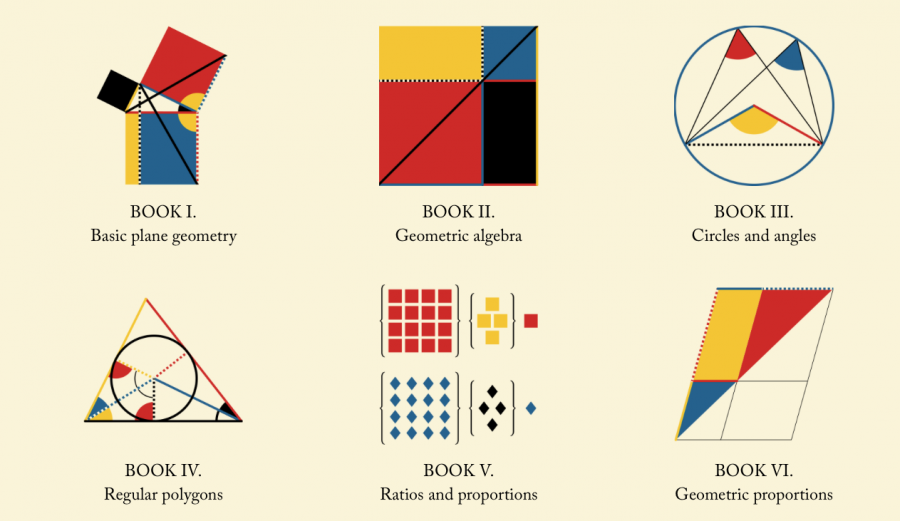

In 1847, maybe sensing that the popularity of Euclid’s text was fading, Irish professor of mathematics Oliver Byrne worked with London publisher William Pickering to produce his own edition of the Elements, or half of it, with original illustrations that carefully explain the text.

“Byrne’s edition was one of the first multicolor printed books,” writes designer Nicholas Rougeux. “The precise use of colors and diagrams meant that the book was very challenging and expensive to reproduce.” It met with little notice at the time.

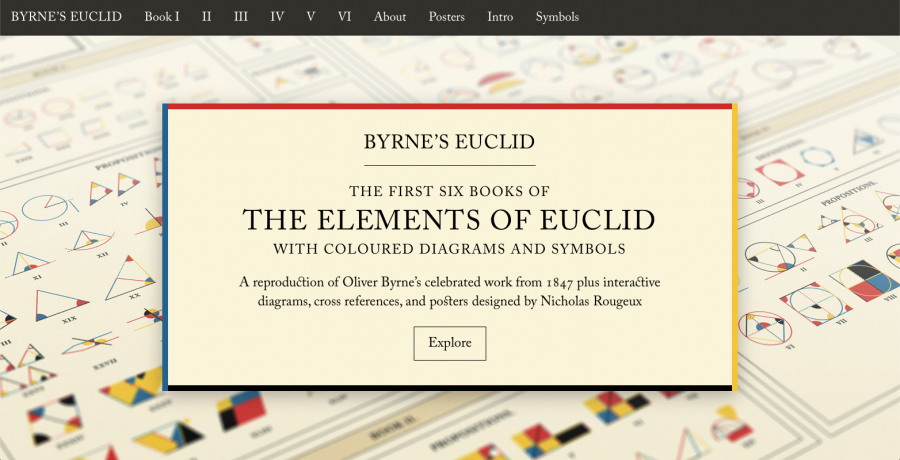

Byrne’s edition—The First Six Books of The Elements of Euclid in which Coloured Diagrams and Symbols are Used Instead of Letters for the Greater Ease of Learners—might have passed into obscurity had a reference to it in Edward Tufte’s Envisioning Information not sparked renewed interest. From there followed a beautiful new edition by TASCHEN and an article on Byrne’s diagrams in mathematics journal Convergence. Rougeux picked up the thread and decided to create an online version. “Like others,” he writes, “I was drawn to its beautiful diagrams and typography.” He has done both of those features ample justice.

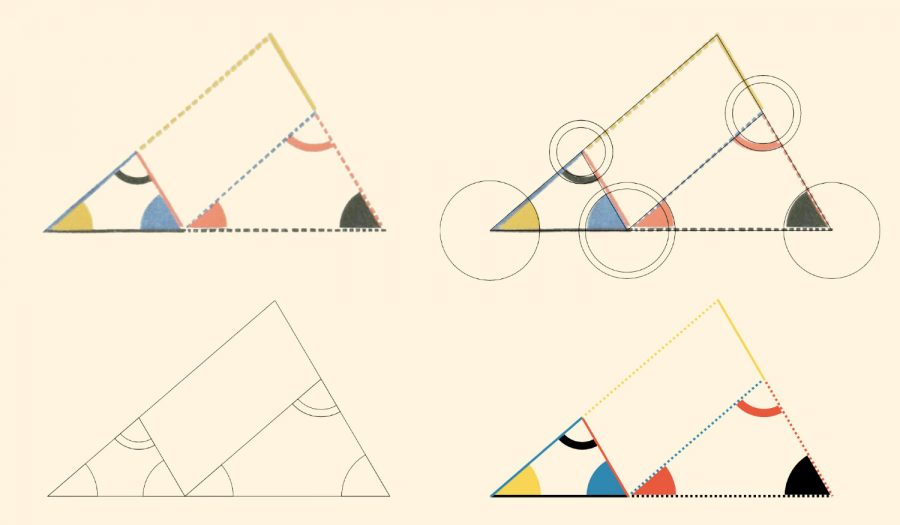

As in another of Rougeux’s online reproductions—his Werner’s Nomenclature of Colours—the designer has taken a great deal of care to preserve the original intentions while adapting the book to the web. In this case, that means the spelling (including the use of the long s), typeface (Caslon), stylized initial capitals, and Byrne’s alternate designs for mathematical symbols have all been retained. But Rougeux has also made the diagrams interactive, “with clickable shapes to aid in understanding the shapes being referenced.”

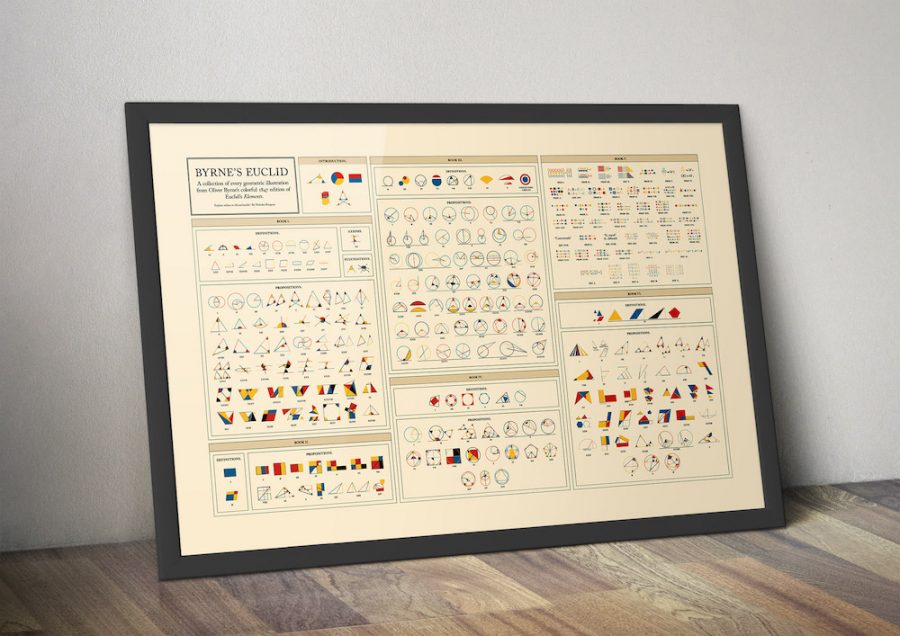

He has also turned all of those lovely diagrams into an attractive poster you can hang on the wall for quick reference or as a conversation piece, though this semaphore-like arrangement of illustrations—like the simplified Euclid in modern textbooks—cannot replace or supplant the original text. You can read Euclid in ancient Greek (see a primer here), in Latin and Arabic, in English translations here, here, here, and many other places and languages as well.

For an experience that combines, however, the best of ancient wisdom and modern information technology—from both the 19th and the 21st centuries—Rougeux’s free, online edition of Byrne’s Euclid can’t be beat. Learn more about the meticulous process of recreating Byrne’s text and diagrams (illustrated above) here.

Related Content:

The Map of Mathematics: Animation Shows How All the Different Fields in Math Fit Together

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness