The internet, one occasionally hears, has overtaken the function of the library. In terms of storing and making accessible all of human knowledge, the ways in which the capacities of the internet match or exceed those of even the most enormous library seem obvious. In theory, digital libraries don’t burn down, at least when properly set up, nor, with their ability to exist above national boundaries, do they get sacked by invading armies. Even so, as Google recently proved when its years-long book-digitization effort Project Ocean came up against legal obstacles, the physical realm hasn’t quite ceded to the online one.

“When the library at Alexandria burned it was said to be an ‘international catastrophe,’ ” writes The Atlantic’s James Somers in a piece on the ambitious, troubled project. When the court ruled against Google’s version, though, fewer tears were shed.

At least when Heidelberg’s Bibliotheca Palatina, the most important library of the Germain Renaissance, became a piece of booty in the Thirty Years’ War in 1622, its 5,000 printed books and 3,524 manuscripts remained, in some sense, available — albeit split, from then on, between Heidelberg and the Vatican’s Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

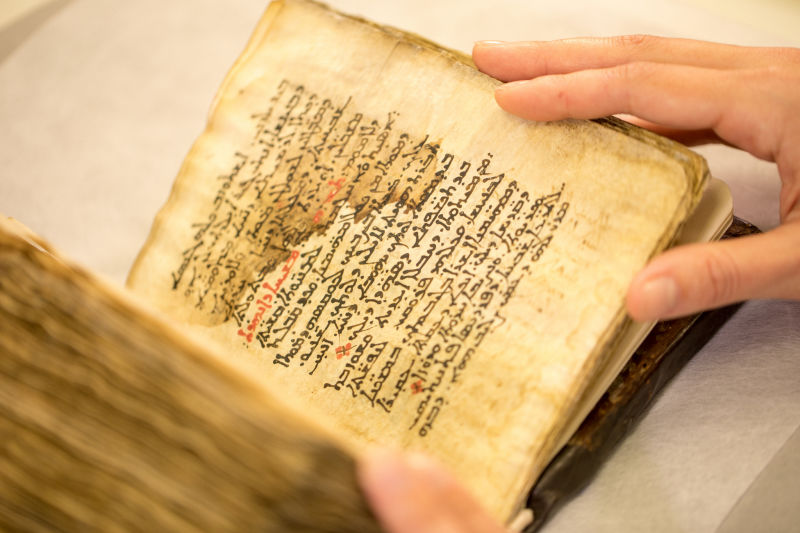

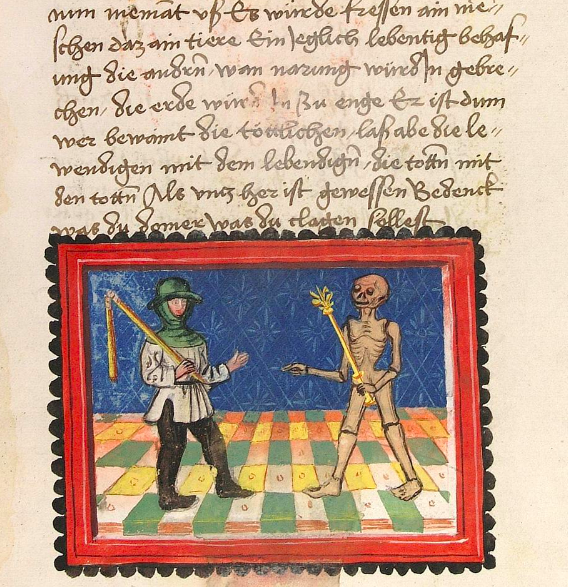

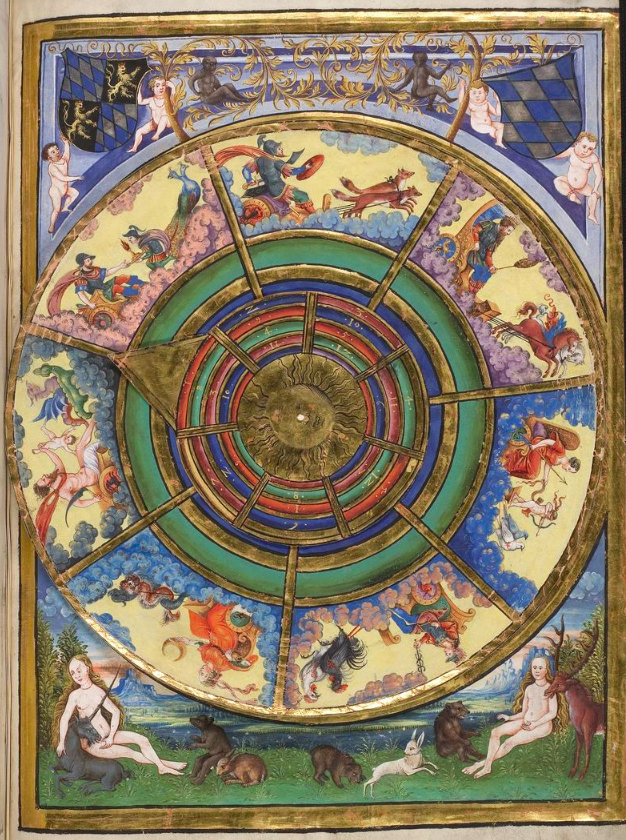

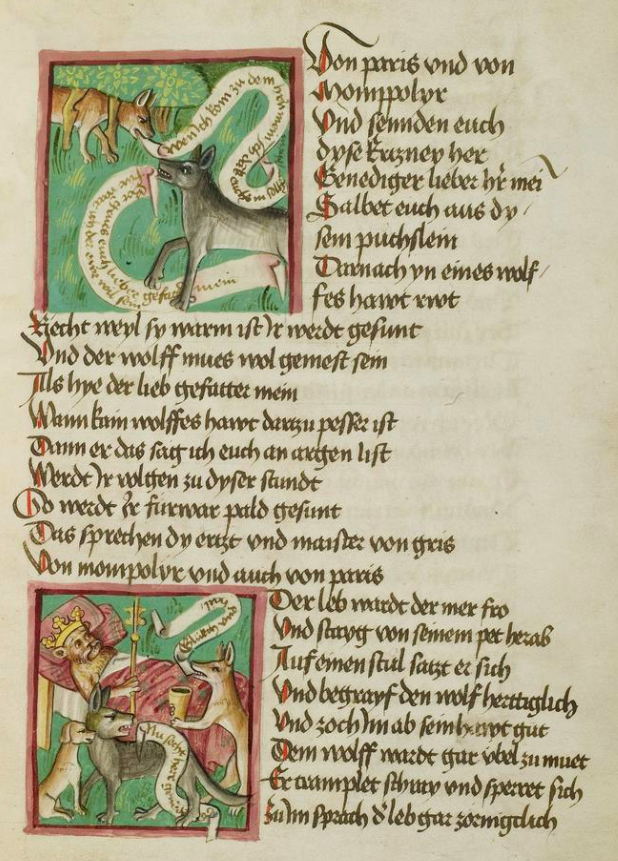

“At the beginning of the 17th century,” says Medievalists.net, the Bibliotheca Palatina “was known as ‘the greatest treasure of Germany’s learned.’ As a universal library, it contains not only theological, philological, philosophical, and historical works but also medical, natural history, and astronomical texts.” Now, its “core inventory” of approximately 3,000 manuscripts has become available free online at the Bibliotheca Palatina Digital. Since 2001, says its site, “Heidelberg University Library has been working on several projects that aim to digitize parts of this great collection, the final goal being a complete virtual reconstruction of the ‘mother of all libraries.’ ”

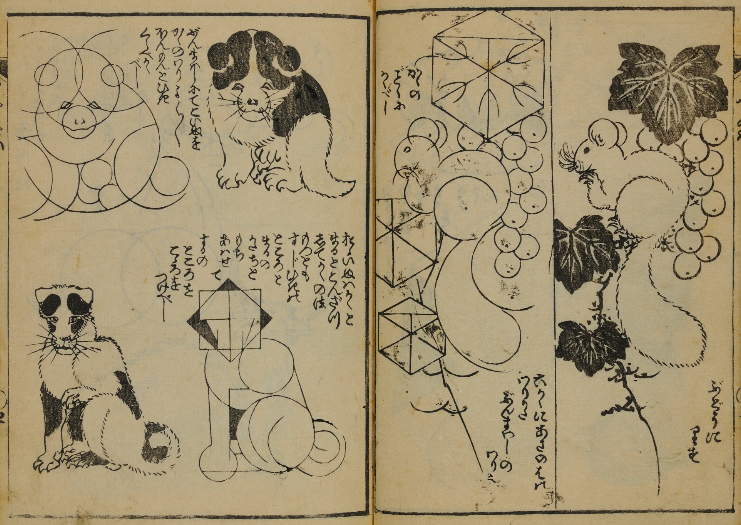

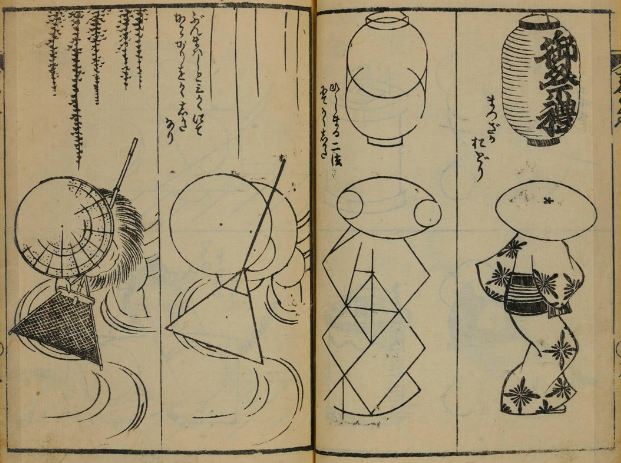

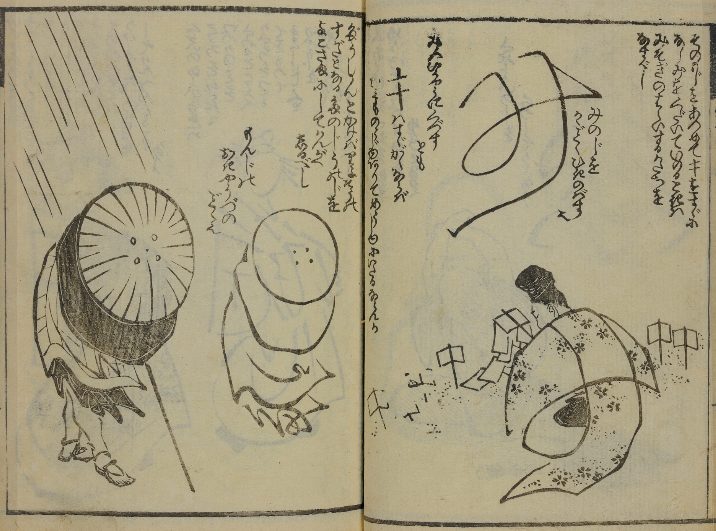

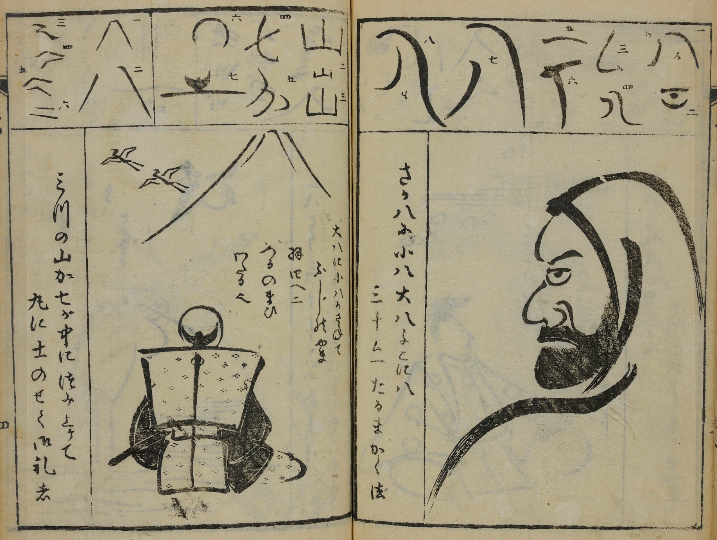

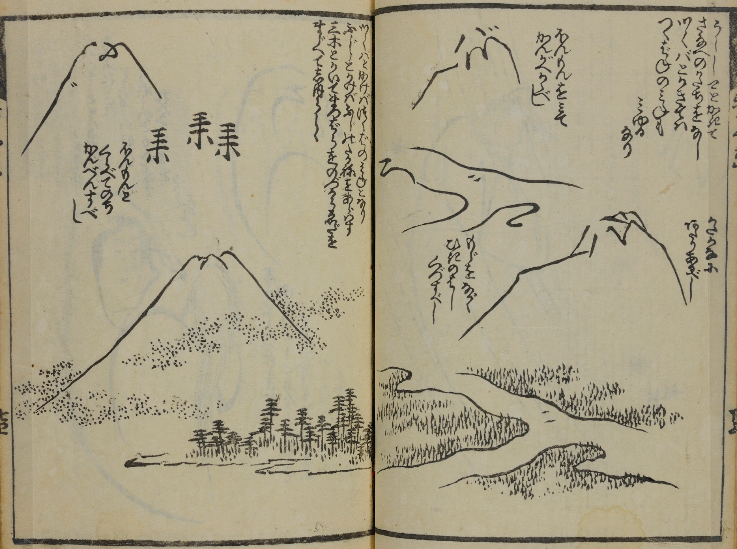

From there you can browse the Bibliotheca Palatina Digital’s Codices Palatini germanici, “the largest and oldest undivided collection of extant German-language manuscripts”; the Codices Palatini latini, where “you will eventually be able to access more than 2,000 Latin manuscripts”; and the Codices Palatini graeci, which houses “digital facsimiles of 29 Greek manuscripts which are now kept in Heidelberg University Library.” It also offers sections on the history of the Bibliotheca Palatina; on the Codex Manesse, “the world’s richest anthology of mediaeval German song”; and (for now in German only) on the manuscripts’ decorations and the insight they provide into “the thematically diverse art of mediaeval book-making.” And none of it subject to sacking — unless, of course, history has a particularly nasty surprise in store for us.

Enter the Digital Bibliotheca Palatina here.

Related Content:

Discover the Jacobean Traveling Library: The 17th Century Precursor to the Kindle

Wonderfully Weird & Ingenious Medieval Books

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.