However detailed they may be in other respects, many accounts of daily life centuries and centuries ago pass over the use of the toilet in silence. Even if they didn’t, they wouldn’t involve the kind of toilets we would recognize today, but rather chamber pots, outhouses, and other kinds of specialized rooms with chutes emptying straight out into rivers and onto back gardens. And that was just the residences. What would public facilities have been like? We have one answer in the Told in Stone video above, which describes “public latrines in ancient Rome,” the facilities constructed in almost every Roman town “where citizens could relieve themselves en masse.”

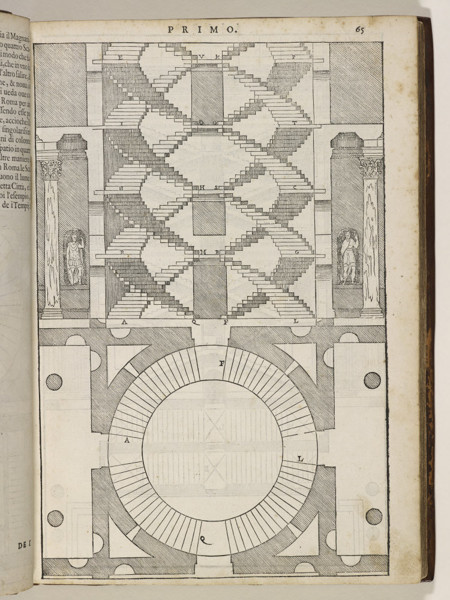

These usually had at least a dozen seats, Told in Stone creator Garrett Ryan explains, though some were grander in scale than others: the Roman agora of Athens, for example, boasted a 68-seater. A facility in Timgad, the “African Pompeii” previously featured here on Open Culture, had “fancy armrests in the shape of leaping dolphins.”

Judged by their ruins, these public “restrooms” may seem unexpectedly impressive in their engineering and elegant in their design. But we may feel somewhat less inclined toward time-travel fantasies when Ryan gets into such details as “the sponge on a stick that served as toilet paper” that remains “one of the more notorious aspects of daily life in ancient Rome.”

These weren’t technically latrines, as Lina Zeldovich notes at Smithsonian.com. “The word ‘latrine,’ or latrina in Latin, was used to describe a private toilet in someone’s home, usually constructed over a cesspit. Public toilets were called foricae,” and their construction tended to rely on deep-pocketed organizations or individuals. “Upper-class Romans, who sometimes paid for the foricae to be erected, generally wouldn’t set foot in these places. They constructed them for the poor and the enslaved — but not because they took pity on the lower classes. They built these public toilets so they wouldn’t have to walk knee-deep in excrement on the streets.”

The problem of large-scale human waste disposal is as old as urban civilization, and Rome hardly solved it once and for all. The Absolute History short above shows how the castles of medieval England handled it, using lavatories with holes over the moat (and piles of “moss, grass, or hay” in lieu of yet-to-be-invented toilet paper). At Medievalists.net, Lucie Laumonier writes that the urban equivalent of Roman foricae were “often built over bridges and on quays to facilitate the evacuation of human waste that went directly into running water.” Innovative as this was, it must have posed difficulties for boaters passing below, to say nothing of the users unfortunate enough to sit on a wooden seat just rotten enough to give out — the prospect of which, for all the deficiencies of Modern Western civilization’s public restrooms, at least no longer worries us quite so much today.

Related content:

Everything You Wanted to Know About Going to the Bathroom in Space But Were Afraid to Ask

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.