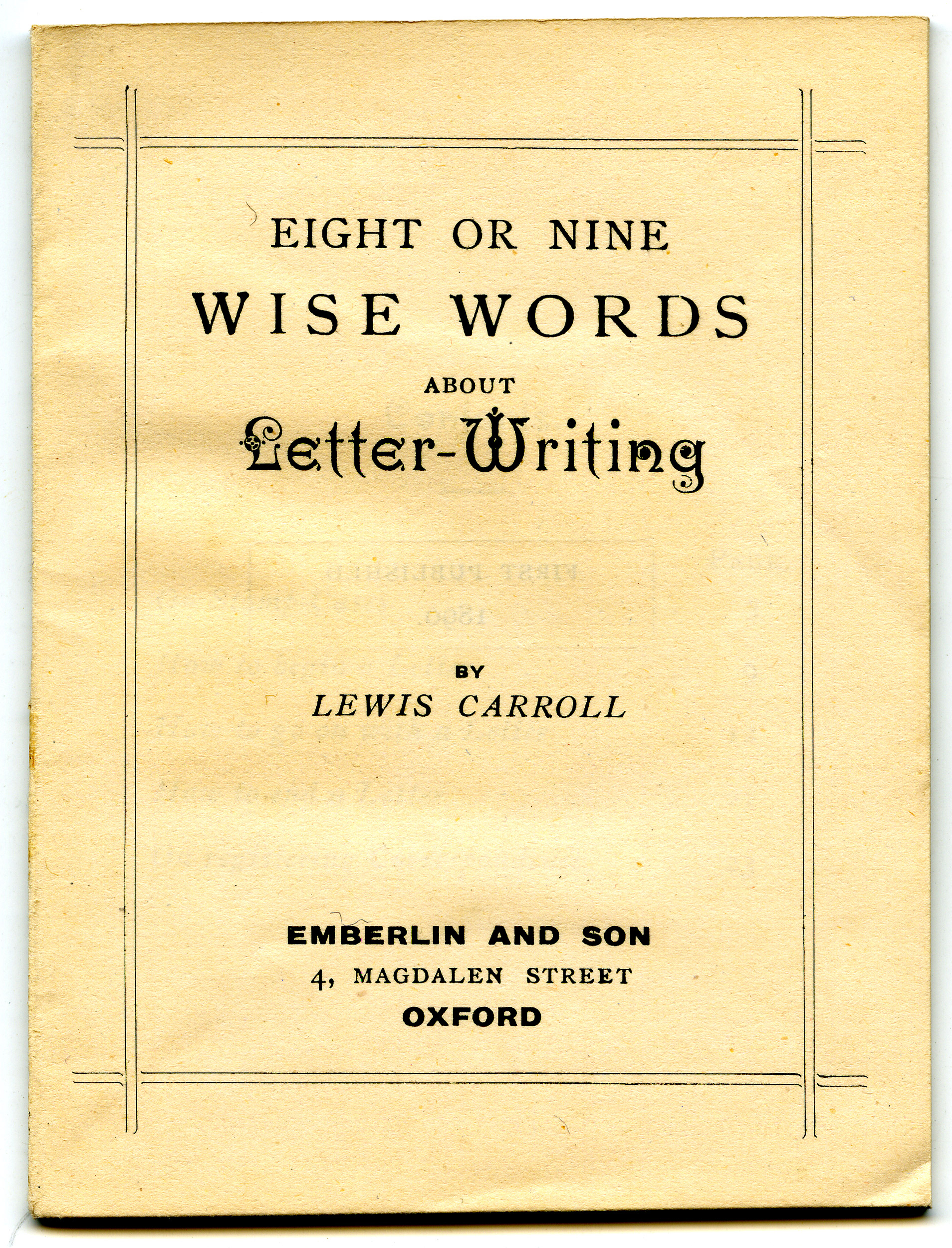

My graduate school supervisor taught me all I know about professional email etiquette. Vague language? Poor form. Typos? Nothing worse. Run-on paragraphs? A big no-no. Spelling your recipient’s name wrong? No coming back from that one. Unfortunately, hastily composed emails and ambiguous phrasing are all too common, particularly with the high volume of emails many people send daily. Skimping on the courtesy and the proofreading, however, is likely to cost you points with your recipient. Thankfully, we’ve provided a list of correspondence best practices, compiled by an authority on letters: Lewis Carroll (who, incidentally, would have celebrated his 182nd birthday today). In 1890, Carroll began to sell a Wonderland Stamp Case, which helped its users to organize their various postage stamps. Paired with the case was a short essay, entitled “Eight Or Nine Wise Words About Letter-Writing.”

The initial guide, of course, refers to pen and paper correspondence. In fact, Carroll’s foremost precept, which instructs one to write legibly, is no longer a concern in the digital age. Nevertheless, the remaining eight rules provide a clear and simple crib sheet for letter-writing that has stood the test of time remarkably well:

1) Start by addressing any questions the receiver previously had - “Don’t fill more than a page and a half with apologies for not having written sooner!

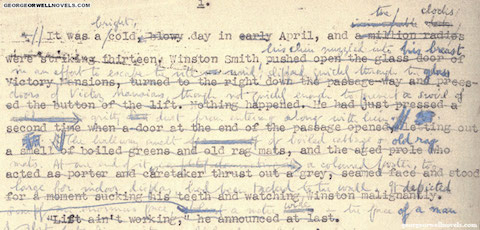

The best subject, to begin with, is your friend’s last letter. Write with the letter open before you. Answer his questions, and make any remarks his letter suggests. Then go on to what you want to say yourself. This arrangement is more courteous, and pleasanter for the reader, than to fill the letter with your own invaluable remarks, and then hastily answer your friend’s questions in a postscript. Your friend is much more likely to enjoy your wit, after his own anxiety for information has been satisfied.”

2) Don’t repeat yourself - “When once you have said your say, fully and clearly, on a certain point, and have failed to convince your friend, drop that subject: to repeat your arguments, all over again, will simply lead to his doing the same…”

3) Write with a level head — “When you have written a letter that you feel may possibly irritate your friend, however necessary you may have felt it to so express yourself, put it aside till the next day. Then read it over again, and fancy it addressed to yourself. This will often lead to your writing it all over again, taking out a lot of the vinegar and pepper, and putting in honey instead, and thus making a much more palatable dish of it!”

4) When in doubt, err on the side of courtesy - “If your friend makes a severe remark, either leave it unnoticed, or make your reply distinctly less severe: and if he makes a friendly remark, tending towards ‘making up’ the little difference that has arisen between you, let your reply be distinctly more friendly. If, in picking a quarrel, each party declined to go more than three-eighths of the way, and if, in making friends, each was ready to go five-eighths of the way—why, there would be more reconciliations than quarrels! Which is like the Irishman’s remonstrance to his gad-about daughter—‘Shure, you’re always goin’ out! You go out three times, for wanst that you come in!’ ”

5) Don’t try to have the last word — “How many a controversy would be nipped in the bud, if each was anxious to let the other have the last word! Never mind how telling a rejoinder you leave unuttered: never mind your friend’s supposing that you are silent from lack of anything to say: let the thing drop, as soon as it is possible without discourtesy: remember ‘speech is silvern, but silence is golden’! (N.B.—If you are a gentleman, and your friend a lady, this Rule is superfluous: you won’t get the last word!)”

6) Humor is hard to translate to writing. Be obvious. - “If it should ever occur to you to write, jestingly, in dispraise of your friend, be sure you exaggerate enough to make the jesting obvious: a word spoken in jest, but taken as earnest, may lead to very serious consequences. I have known it to lead to the breaking-off of a friendship. Suppose, for instance, you wish to remind your friend of a sovereign you have lent him, which he has forgotten to repay—you might quite mean the words “I mention it, as you seem to have a conveniently bad memory for debts”, in jest: yet there would be nothing to wonder at if he took offence at that way of putting it. But, suppose you wrote “Long observation of your career, as a pickpocket and a burglar, has convinced me that my one lingering hope, for recovering that sovereign I lent you, is to say ‘Pay up, or I’ll summons yer!’” he would indeed be a matter-of-fact friend if he took that as seriously meant!”

7) Don’t forget that attachment! — “When you say, in your letter, “I enclose cheque for £5”, or “I enclose John’s letter for you to see”, leave off writing for a moment—go and get the document referred to—and put it into the envelope. Otherwise, you are pretty certain to find it lying about, after the Post has gone!”

8) Using a postscript? Make it short — “A Postscript is a very useful invention: but it is not meant (as so many ladies suppose) to contain the real gist of the letter: it serves rather to throw into the shade any little matter we do not wish to make a fuss about.”

Casual Victorian-era “silly women!” sexism aside, Carroll’s tips are surprisingly fresh and applicable. If you’re planning on engaging in some serious snail-mail correspondence, we suggest you check out Carroll’s complete essay over at Project Gutenberg.

Ilia Blinderman is a Montreal-based culture and science writer. Follow him at @iliablinderman.

Related Content:

See Salvador Dali’s Illustrations for the 1969 Edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

The Real Alice in Wonderland Circa 1862