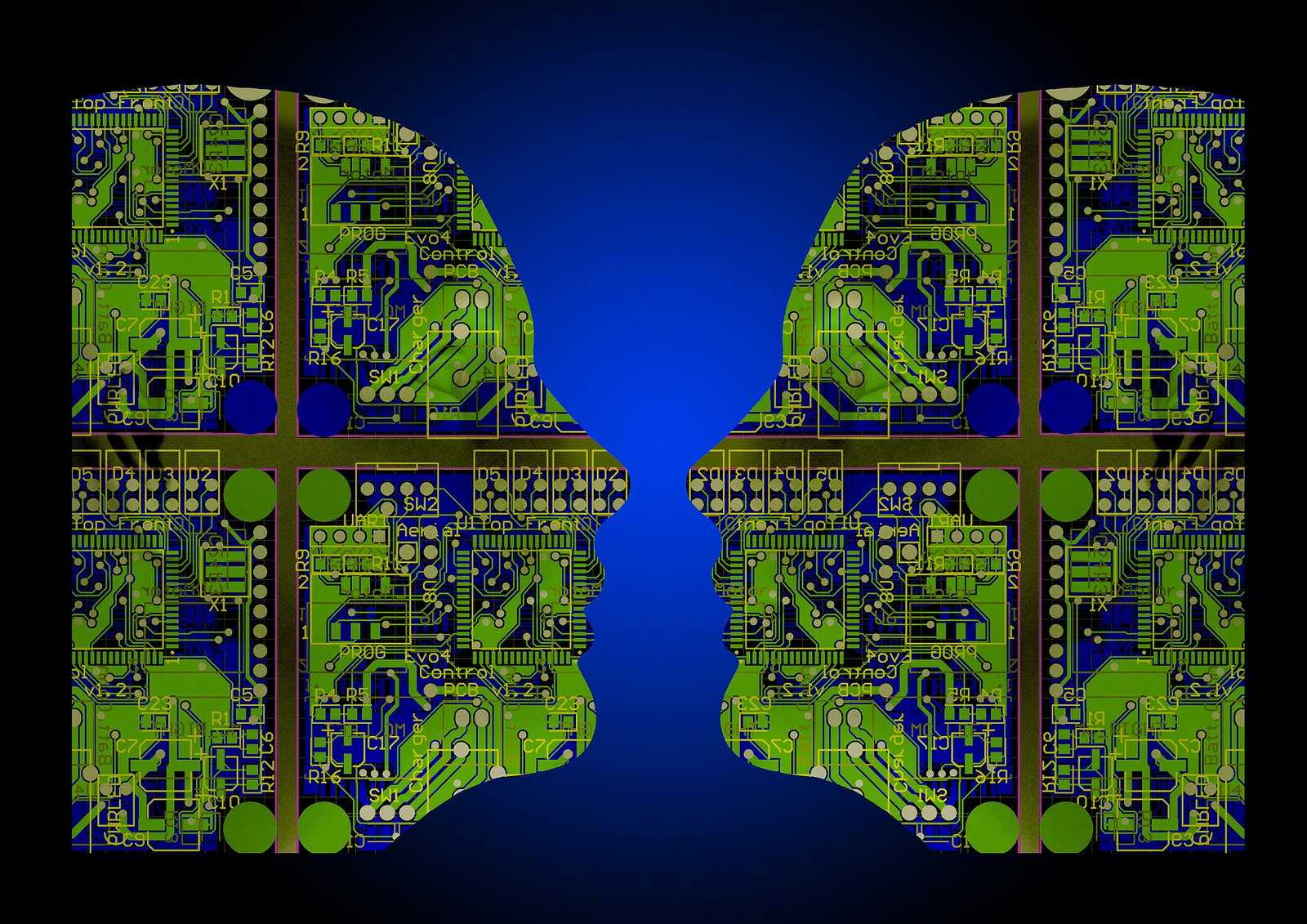

We know they’re coming. The robots. To take our jobs. While humans turn on each other, find scapegoats, try to bring back the past, and ignore the future, machine intelligences replace us as quickly as their designers get them out of beta testing. We can’t exactly blame the robots. They don’t have any say in the matter. Not yet, anyway. But it’s a fait accompli say the experts. “The promise,” writes MIT Technology Review, “is that intelligent machines will be able to do every task better and more cheaply than humans. Rightly or wrongly, one industry after another is falling under its spell, even though few have benefited significantly so far.”

The question, then, is not if, but “when will artificial intelligence exceed human performance?” And some answers come from a paper called, appropriately, “When Will AI Exceed Human Performance? Evidence from AI Experts.” In this study, Katja Grace of the Future of Humanity Institute at the University of Oxford and several of her colleagues “surveyed the world’s leading researchers in artificial intelligence by asking them when they think intelligent machines will better humans in a wide range of tasks.”

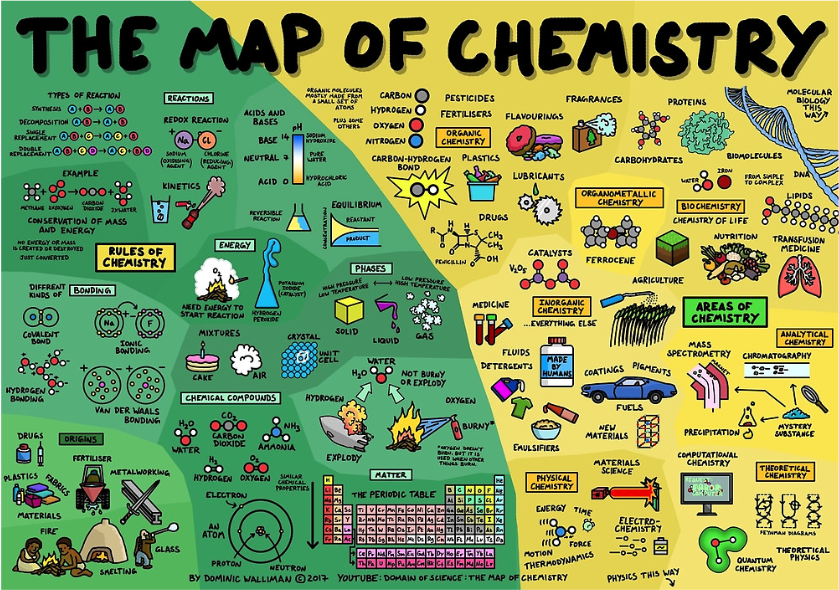

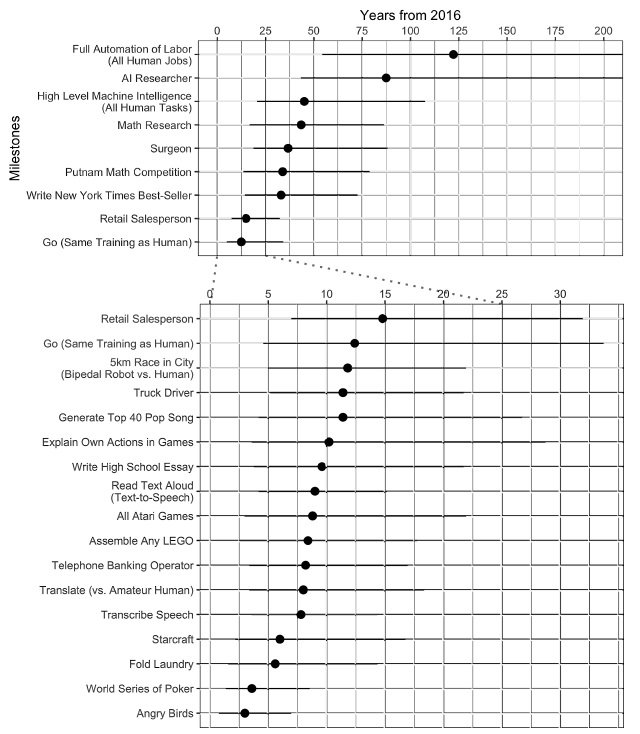

You can see many of the answers plotted on the chart above. Grace and her co-authors asked 1,634 experts, and found that they “believe there is a 50% chance of AI outperforming humans in all tasks in 45 years and of automating all human jobs in 120 years.” That means all jobs: not only driving trucks, delivering by drone, running cash registers, gas stations, phone support, weather forecasts, investment banking, etc, but also performing surgery, which may happen in less than 40 years, and writing New York Times bestsellers, which may happen by 2049.

That’s right, AI may perform our cultural and intellectual labor, making art and films, writing books and essays, and creating music. Or so the experts say. Already a Japanese AI program has written a short novel, and almost won a literary prize for it. And the first milestone on the chart has already been reached; last year, Google’s AI AlphaGo beat Lee Sedol, the South Korean grandmaster of Go, the ancient Chinese game “that’s exponentially more complex than chess,” as Cade Metz writes at Wired. (Humane video game design, on the other hand, may have a ways to go yet.)

Perhaps these feats partly explain why, as Grace and the other researchers found, Asian respondents expected the rise of the machines “much sooner than North America.” Other cultural reasons surely abound—likely those same quirks that make Americans embrace creationism, climate-denial, and fearful conspiracy theories and nostalgia by the tens of millions. The future may be frightening, but we should have seen this coming. Sci-fi visionaries have warned us for decades to prepare for our technology to overtake us.

In the 1960s Alan Watts foresaw the future of automation and the almost pathological fixation we would develop for “job creation” as more and more necessary tasks fell to the robots and human labor became increasingly superfluous. (Hear him make his prediction above.) Like many a technologist and futurist today, Watts advocated for Universal Basic Income, a way of ensuring that all of us have the means to survive while we use our newly acquired free time to consciously shape the world the machines have learned to maintain for us.

What may have seemed like a Utopian idea then (though it almost became policy under Nixon), may become a necessity as AI changes the world, writes MIT, “at breakneck speed.”

via Big Think/MIT Technology Review

Related Content:

Hear Alan Watts’s 1960s Prediction That Automation Will Necessitate a Universal Basic Income

Bertrand Russell & Buckminster Fuller on Why We Should Work Less, and Live & Learn More

Artificial Intelligence Program Tries to Write a Beatles Song: Listen to “Daddy’s Car”

Artificial Intelligence: A Free Online Course from MIT

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness