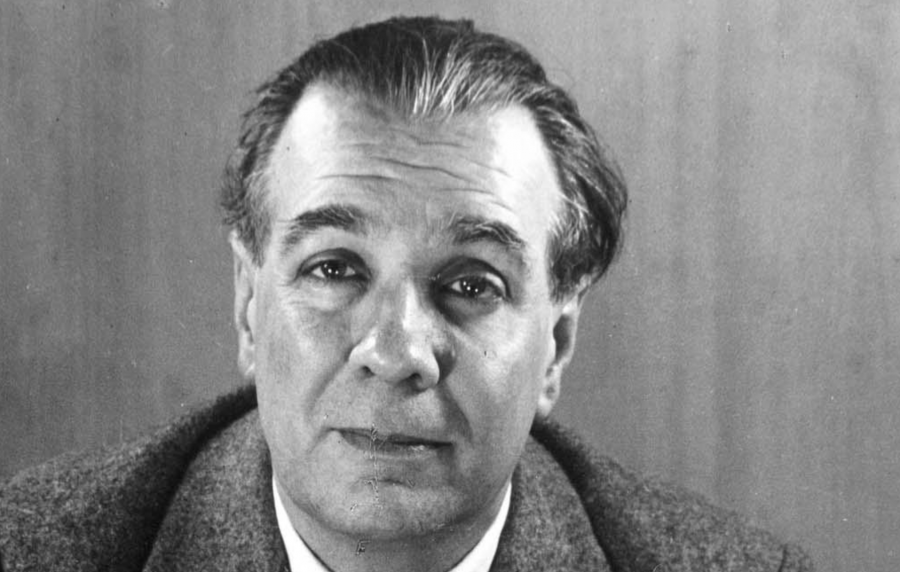

So you want to be a writer? Good, you’ll find plenty of advice from the best here at Open Culture. Oh, you want to be a science fiction writer? The great Ursula K. Le Guin has offered readers a wealth of writing advice, though she won’t tell us “how to sell a ship, but how to sail one.” But wait, you also want to know how to publish, and make a living? For that, you’d better see Robert Heinlein, one of the acknowledged masters of the Golden Age of science fiction and a hugely prolific author who pioneered both popular hard sci-fi and what he called “speculative fiction,” a more serious, literary form incorporating social and political themes.

In his 1947 essay “On the Writing of Speculative Fiction,” Heinlein refers to these “two types” of science fiction as “the gadget story and the human interest story.” The latter kind of story, writes Heinlein “stands a better chance with the slicks than a gadget story does” because it has wider appeal. This advice sounds rather utilitarian, doesn’t it? What about passion, inspiration, the muse? Eh, you don’t have time for those things. If you want to be successful like Robert Heinlein, you’ve got to write stories, lots of ‘em, stories people want to publish and pay for, stories people want to read.

Heinlein spends the bulk of his essay advising us on how to write such stories, with a proviso, in an epigram from Rudyard Kipling, that “there are nine-and-sixty ways / Of constructing tribal lays / And every single one of them is right.” After, however, describing in detail how he writes a “human interest” science fiction story, Heinlein then gets down to business. He assumes that we can type, know the right formats or can learn them, and can spell, punctuate, and use grammar as our “wood-carpenter’s sharp tools.” These prerequisites met, all we really need to write speculative fiction are the five rules below:

1. You must write.

2. You must finish what you start.

3. You must refrain from rewriting except to editorial order.

4. You must put it on the market.

5. You must keep it on the market until sold.

You might think Heinlein has lapsed into the language of the realtor, not the writer, but he is deadly serious about these rules, which “are amazingly hard to follow—which is why there are so few professional writers and so many aspirants.” Anyone who has tried to write and publish fiction knows this to be true. But what did Heinlein mean in giving us such an austere list? For one thing, as he notes many times, there are perhaps as many ways to write sci-fi stories as there are people to write them. What Heinlein aims to give us are the keys to becoming professional writers, not theorists of writing, lovers of writing, dabblers and dilettantes of writing.

Award-winning science fiction writer Robert J. Sawyer has interpreted Heinlein’s rules with commentary of his own, and added a sixth: “Start Working on Something Else.” Good advice. Heinlein’s rule number three, however—“the one that got Heinlein in trouble with creative-writing teachers”—seems to contradict what most every other writer will tell us. Sawyer suggests we take it to mean, “Don’t tinker endlessly with your story.” Writer Patricia C. Wrede agrees, but also suggests that “Heinlein was of the school of thought that felt that ‘good enough’ was all that was necessary, ever.”

Like 19th century writers who churned out novels as serialized stories for the papers and magazines, Heinlein and his fellow Golden Age writers made their living selling story after story to the “pulps” and the “slicks” (preferably the slicks). One had to be prolific, and being “’prolific enough’ often involved not having time to polish and revise much (if at all).” So rule number three may or may not apply, depending on our constraints. The literary market has changed dramatically since 1947, but the rest of Heinlein’s rules still seem nonnegotiable if we intend not only to write—speculative fiction or otherwise—but also to make a career doing so.

Related Content:

Writing Tips by Henry Miller, Elmore Leonard, Margaret Atwood, Neil Gaiman & George Orwell

Ray Bradbury Gives 12 Pieces of Writing Advice to Young Authors (2001)

Stephen King’s Top 20 Rules for Writers

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness