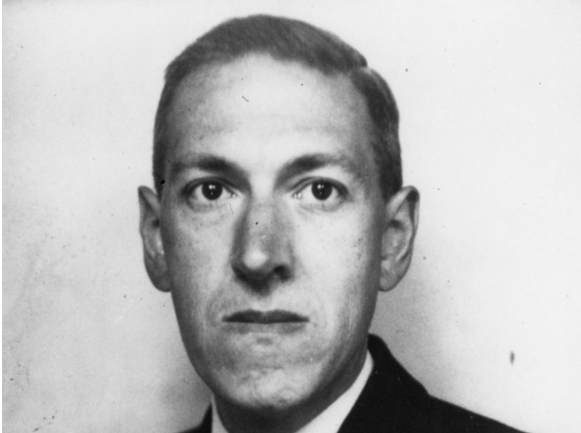

Image by Lucius B. Truesdell, via Wikimedia Commons

Though the term “weird fiction” came into being in the 19th century—originally used by Irish gothic writer Sheridan Le Fanu—it was picked up by H.P. Lovecraft in the 20th century as a way, primarily, of describing his own work. Lovecraft produced copious amounts of the stuff, as you can see from our post highlighting online collections of nearly his entire corpus. He also wrote in depth about writing itself. He did so in generally prescriptive ways, as in his 1920 essay “Literary Composition,” and in ways specific to his chosen mode—as in the 1927 “Supernatural Horror in Literature,” in which he defined weird fiction very differently than Le Fanu or modern authors like China Miéville. For Lovecraft,

The true weird tale has something more than secret murder, bloody bones, or a sheeted form clanking chains according to rule. A certain atmosphere of breathless and unexplainable dread of outer, unknown forces must be present; and there must be a hint, expressed with a seriousness and portentousness becoming its subject, of that most terrible conception of the human brain–a malign and particular suspension or defeat of those fixed laws of Nature which are our only safeguard against the assaults of chaos and the daemons of unplumbed space.

Here we have, broadly, the template for a very Lovecraftian tale indeed. Ten years later, in a 1937 essay titled “Notes on Writing Weird Fiction,” Lovecraft would return to the theme and elaborate more fully on how to produce such an artifact.

Weird Fiction, wrote Lovecraft in that later essay, is “obviously a special and perhaps a narrow” kind of “story-writing,” a form in which “horror and the unknown or the strange are always closely connected,” and one that “frequently emphasize[s] the element of horror because fear is our deepest and strongest emotion.” Although Lovecraft self-deprecatingly calls himself an “insignificant amateur,” he nonetheless situates himself in the company of “great authors” who mastered horror writing of one kind or another: “[Lord] Dunsany, Poe, Arthur Machen, M.R. James, Algernon Blackwood, and Walter de la Mare.” Even if you only know the name of Poe, it’s weighty company indeed.

But be not intimidated—Lovecraft wasn’t. As our traditional holiday celebration of fear approaches, perhaps you’d be so inclined to try your hand at a little weird fiction of your own. You should certainly, Lovecraft would stress, spend some time reading these writers’ works. But he goes further, and offers us a very concise, five point “set of rules” for writing a weird fiction story that he says might be “deduced… if the history of all my tales were analyzed.” See an abridged version below:

- Prepare a synopsis or scenario of events in the order of their absolute occurrence—not the order of their narrations.

This is a practice adhered to by writers from J.K. Rowling and William Faulkner to Norman Mailer. It seems an excellent general piece of advice for any kind of fiction.

- Prepare a second synopsis or scenario of events—this one in order of narration (not actual occurrence), with ample fullness and detail, and with notes as to changing perspective, stresses, and climax.

- Write out the story—rapidly, fluently, and not too critically—following the second or narrative-order synopsis. Change incidents and plot whenever the developing process seems to suggest such change, never being bound by any previous design.

It may be that the second rule is made just to be broken, but it provides the weird fiction practitioner with a beginning. The third stage here brings us back to a process every writer on writing, such as Stephen King, will highlight as key—free, unfettered drafting, followed by…

- Revise the entire text, paying attention to vocabulary, syntax, rhythm of prose, proportioning of parts, niceties of tone, grace and convincingness of transitions…

And finally….

- Prepare a neatly typed copy—not hesitating to add final revisory touches where they seem in order.

You will notice right away that these five “rules” tell us nothing about what to put in our weird fiction, and could apply to any sort of fiction at all, really. This is part of the admirably comprehensive quality of the otherwise succinct essay. Lovecraft tells us why he writes, why he writes what he writes, and how he goes about it. The content of his fictional universe is entirely his own, a method of visualizing “vague, elusive, fragmentary impressions.” Your mileage, and your method, will indeed vary.

Lovecraft goes on to describe “four distinct types of weird story” that fit “into two rough categories—those in which the marvel or horror concerns some condition or phenomenon, and those in which it concerns some action of persons in connection with a bizarre condition or phenonmenon.” If this doesn’t clear things up for you, then perhaps a careful reading of Lovecraft’s complete “Notes on Writing Weird Fiction” will. Ultimately, however, “there is no one way” to write a story. But with some practice—and no small amount of imagination—you may find yourself joining the company of Poe, Lovecraft, and a host of contemporary writers who continue to push the boundaries of weird fiction past the sometimes parochial, often profoundly bigoted, limits that Lovecraft set out.

Related Content:

H.P. Lovecraft’s Classic Horror Stories Free Online: Download Audio Books, eBooks & More

Lovecraft: Fear of the Unknown (Free Documentary)

Stephen King’s Top 20 Rules for Writers

Writing Tips by Henry Miller, Elmore Leonard, Margaret Atwood, Neil Gaiman & George Orwell

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness