Napoleon’s Kindle: Discover the Miniaturized Traveling Library That the Emperor Took on Military Campaigns

Every piece of technology has a precedent. Most have several different types of precedents. You’ve probably used (and may well own) an eBook reader, for instance, but what would have afforded you a selection of reading material two or three centuries ago? If you were a Jacobean Englishman of means, you might have used the kind of traveling library we featured in 2017, a handsome portable case custom-made for your books. (If you’re Tom Stoppard in the 21st century, you still do.) If you were Napoleon, who seemed to love books as much as he loved military power — he didn’t just amass a vast collection of them, but kept a personal librarian to oversee it — you’d take it a big step further.

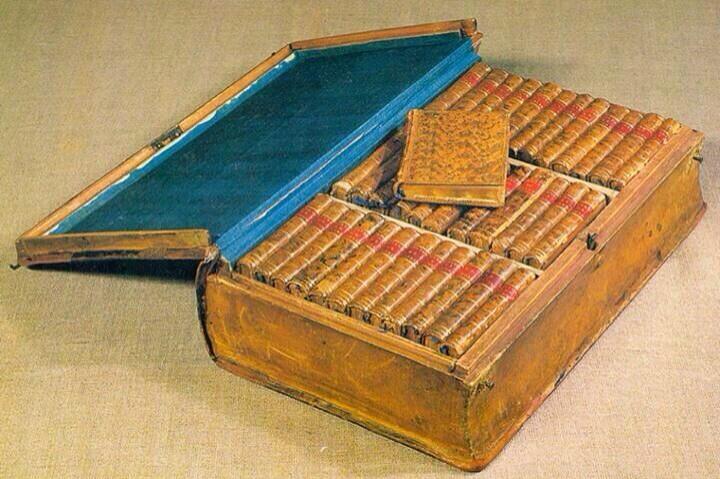

“Many of Napoleon’s biographers have incidentally mentioned that he […] used to carry about a certain number of favorite books wherever he went, whether traveling or camping,” says an 1885 Sacramento Daily Union article posted by Austin Kleon, “but it is not generally known that he made several plans for the construction of portable libraries which were to form part of his baggage.” The piece’s main source, a Louvre librarian who grew up as the son of one of Napoleon’s librarians, recalls from his father’s stories that “for a long time Napoleon used to carry about the books he required in several boxes holding about sixty volumes each,” each box first made of mahogany and later of more solid leather-covered oak. “The inside was lined with green leather or velvet, and the books were bound in morocco,” an even softer leather most often used for bookbinding.

To use this early traveling library, Napoleon had his attendants consult “a catalogue for each case, with a corresponding number upon every volume, so that there was never a moment’s delay in picking out any book that was wanted.” This worked well enough for a while, but eventually “Napoleon found that many books which he wanted to consult were not included in the collection,” for obvious reasons of space. And so, on July 8, 1803, he sent his librarian these orders:

The Emperor wishes you to form a traveling library of one thousand volumes in small 12mo and printed in handsome type. It is his Majesty’s intention to have these works printed for his special use, and in order to economize space there is to be no margin to them. They should contain from five hundred to six hundred pages, and be bound in covers as flexible as possible and with spring backs. There should be forty works on religion, forty dramatic works, forty volumes of epic and sixty of other poetry, one hundred novels and sixty volumes of history, the remainder being historical memoirs of every period.

In sum: not only did Napoleon possess a traveling library, but when that traveling library proved too cumbersome for his many and varied literary demands, he had a whole new set of not just portable book cases but even more portable books made for him. (You can see how they looked packed away in the image tweeted by Cork County Library above.) This prefigured in a highly analog manner the digital-age concept of recreating books in another format specifically for compactness and convenience — the kind of compactness and convenience now increasingly available to all of us today, and to a degree Napoleon never could have imagined, let alone demanded. It may be good to be the Emperor, but in many ways, it’s better to be a reader in the 21st century.

Note: This post was originally published in 2017. Given that Napoleon is back in the news, with the new Ridley Scott film, we’re bringing it back.

Related Content:

Discover the Jacobean Traveling Library: The 17th Century Precursor to the Kindle

Why Is Napoleon’s Hand Always in His Waistcoat?: The Origins of This Distinctive Pose Explained

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Advice for Time Traveling to Medieval Europe: How to Staying Healthy & Safe, and Avoiding Charges of Witchcraft

Generations of foreign tourists in Europe have heard advice about traveling in groups, haggling prices, avoiding pickpockets, and being able to communicate in, if not the local language, then at least the lingua franca. It turns out that very similar guidance applies to time travel in Europe, or at least specifically to the region of England, France, Germany, and northern Italy in the central Middle Ages, roughly between the years 1000 and 1400. In the new video above, history Youtuber Premodernist provides an hour’s worth of advice to the modern preparing to travel back in time to medieval Europe — beginning with the declaration that “you will very likely get sick.”

The gastrointestinal distress posed by the “native biome” of medieval European food and drink is one thing; the threat of robbery or worse by its roving packs of outlaws is quite another. “Crime is rampant” where you’re going, so “carry a dagger” and “learn how to use it.” In societies of the Middle Ages, people could only protect themselves by being “enmeshed in social webs with each other. No one was an individual.” And so, as a traveler, you must — to put it in Dungeons-and-Dragons terms — belong to some legible class. Though you’ll have no choice but to present yourself as having come from a distant land, you can feel free to pick one of two guises that will suit your obvious foreignness: “you’re either a merchant or a pilgrim.”

Unlike modern-day Europe, through which you travel for weeks barely speaking to anyone, the Europe of the Middle Ages offers numerous opportunities for conversation, whether you want them or not. Without any media as we know it today, medievals had to “make their own entertainment by talking to each other,” and if they could talk to a stranger from an exotic land, so much the more entertaining. But having none of our relatively novel ideas that “everybody’s on an equal footing, that everybody’s equal to each other, nobody’s better or worse than anybody else, nobody gets any special treatment,” they’ll guess your social rank and treat you accordingly; you, in turn, would do well to act the part.

Imagining themselves in medieval Europe, many of our contemporaries say things like, “If I go there, they’ll hang me as a witch, or they’ll burn me at the stake as a witch, because I’m wearing modern clothes and because I talk funny.” But that fear (not untainted, perhaps, by a certain self-regard) is unfounded, since medievals “were not scared of people just because they were different. They were scared of people who were different in a way that challenged the social order or threatened social chaos.” Their worldview put religious affiliation above all, without consideration for even the most hotly debated twenty-first-century political or racial battle lines. But then, as we never needed time travel to understand, the past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.

Related content:

A Free Yale Course on Medieval History: 700 Years in 22 Lectures

How to Make a Medieval Manuscript: An Introduction in 7 Videos

What Sex Was Like in Medieval Times?: Historians Look at How People Got It On in the Dark Ages

A Concise Breakdown of How Time Travel Works in Popular Movies, Books & TV Shows

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...

Behold the Jacobean Traveling Library: The 17th Century Forerunner to the Kindle

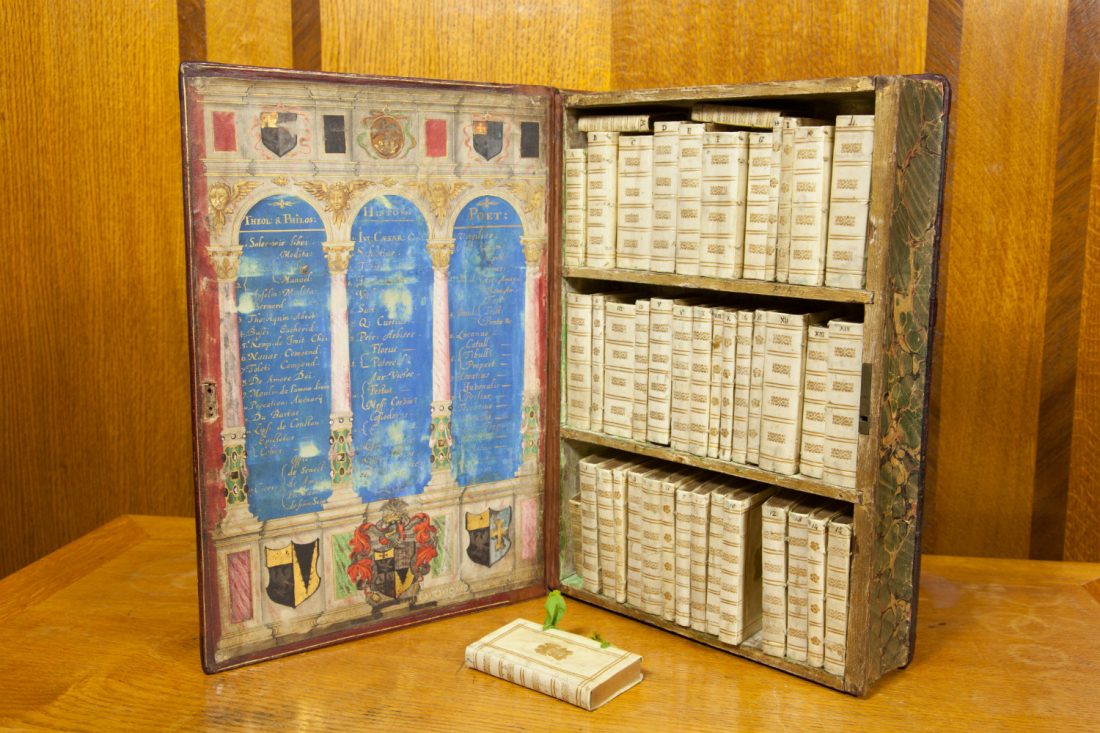

Image courtesy of the University at Leeds

In the striking image above, you can see an early experiment in making books portable–a 17th century precursor, if you will, to the modern day Kindle.

According to the library at the University of Leeds, this “Jacobean Travelling Library” dates back to 1617. That’s when William Hakewill, an English lawyer and MP, commissioned the miniature library–a big book, which itself holds 50 smaller books, all “bound in limp vellum covers with coloured fabric ties.” What books were in this portable library, meant to accompany noblemen on their journeys? Naturally the classics. Theology, philosophy, classical history and poetry. The works of Ovid, Seneca, Cicero, Virgil, Tacitus, and Saint Augustine. Many of the same texts that showed up in The Harvard Classics (now available online) three centuries later.

Apparently three other Jacobean Travelling Libraries were made. They now reside at the British Library, the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, and the Toledo Museum of Art in Toledo, Ohio.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Napoleon’s Kindle: See the Miniaturized Traveling Library He Took on Military Campaigns

The Harvard Classics: Download All 51 Volumes as Free eBooks

The Fiske Reading Machine: The 1920s Precursor to the Kindle

Read More...The Roman Roads and Bridges You Can Still Travel Today

Rare indeed is the ancient-history buff who has never dreamed of walking the roads of the Roman Empire. But unlike many longings stoked by interest in the distant past, that one can actually be fulfilled. As explained in the video above from Youtube channel Intrigued Mind, a fair few Roman roads remain in existence today, albeit only in sections, and mostly ruined ones at that. “Like other incredible monuments that still stand, as if to prove the power of the Roman Empire, there are a surprising number of Roman roads still in use today,” some converted into modern highways, but “many still paved with their original cobblestones.”

Of all such roads, none has more importance than the Via Appia, or Appian Way, whose construction began back in 312 BC. “The first long road outside of the greater city of Rome that wasn’t Etruscan,” it “allowed Romans to make their first major conquest” and begin their mighty empire’s “conquest of the world.” Without understanding the storied Via Appia, none of us can truly understand Roman history. But to grasp the context of the Roman Empire, we can hardly ignore the even older roads like the Via Domitia, which was “the road Hannibal used to invade Italy, 100 years before the Romans claimed it” — not to mention an important setting in the Greek myth of Heracles.

You can still cross one of the Via Domitia’s bridges, the Pont Julien in the south of France. In that same country stand the more-or-less intact Pont Flavian, originally built along the Via Julia Augusta, and the Pont du Gard, the most famous and elegant Roman aqueduct of them all. Nor should enthusiasts of Roman infrastructure miss the Alcantara Bridge in Spain, the Manfred Bridge in Germany, or the ruins of Trajan’s Bridge — made into ruins deliberately, by Trajan’s successor Hadrian — in Romania. The most serious among them will also want to go as far as the Middle East and travel the Via Maris, which connected Egypt to Syria, and the remains of the bridge across Caesar’s Dam in Iran.

Iran belonged, of course, not to the Roman Empire but the Persian one. But “legend has it that the Persian emperor captured the Roman emperor and forced him to use his army to build the dam and the beautiful bridge to cross it.” All was fair, it seems, in the expansion and conflict of ancient empires, and the ruins scattered across their vast former territories testify to that. Though much less technologically advanced than, say, modern freeway systems, the Roman roads that survive have proven surprisingly robust, a phenomenon examined in the video just above by history Youtuber Told in Stone — a Chicagoan, incidentally, who acknowledges that the Via Appia has never had to take a Windy City winter.

Related content:

The Roads of Ancient Rome Visualized in the Style of Modern Subway Maps

The Roman Roads of Britain Visualized as a Subway Map

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

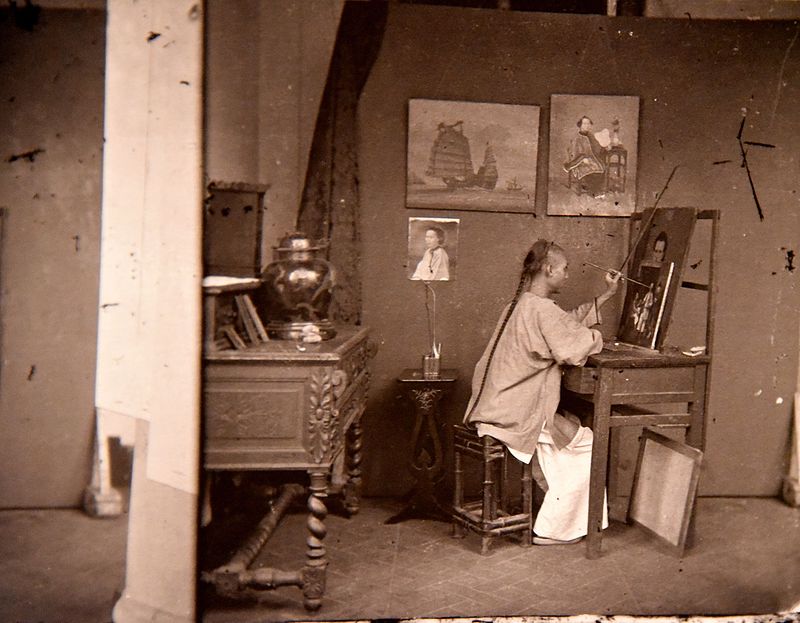

Read More...A Chinese Painter Specializing in Copying Van Gogh Paintings Travels to Amsterdam & Sees Van Gogh’s Masterpieces for the First Time

There are many reasons to look down on art forgery, from its illegality to its lack of originality. But much like any other human endeavor, you need a great deal of skill and stamina to do it well. Certain individual forgers have lived on in history: Han Van Meegeren, say, who tricked the Nazis with his Vermeers, or Elmyr de Hory, whose skills at imitating the styles of Picasso, Matisse, Modigliani, and Renoir landed him in Orson Welles’ F for Fake. If Zhao Xiaoyong doesn’t yet figure among the names of the best-known art forgers, it’s not because nobody’s made a movie about him.

That movie is Yu Haibo and Kiki Tianqi Yu’s documentary China’s Van Goghs, which you can watch just above. Much of it takes place in the village of Dafen in China’s Guangdong province, home to thousands and thousands of oil painters, all of whom make their living making replicas (in various sizes) of famous paintings by the likes of Leonardo, Rembrandt, Dalí, Basquiat, and — above all, it seems — Van Gogh. It speaks to the speed and scale of modern Chinese industry that this activity began only in 1989, but grew such that, at one point, Dafen was supplying 60 percent of the oil paintings in the world.

Zhao arrived in Dafen in the early nineteen-nineties, but still got into its nascent industry quite early on. “Back then, painting in the village hadn’t scaled up yet,” he writes in an essay at The World of Chinese. “I was moved the first time I saw the oil paintings there. They were so delicate. The people’s eyes and skin looked so vivid, so alive.” In Dafen’s small factories, “all of the painters there were rushing to fill orders, so nobody was going to hold my hand.” After his first batch of sales, he made himself a promise to “master the works of Van Gogh.”

At the time, Zhao would have had no way of knowing how close he would eventually get to those works. Even when he established himself to the point that he could start his own studio, the dream of visiting Van Gogh’s homeland — as opposed to selling copies of Van Gogh’s art to Van Gogh’s own countrymen — must have seemed far off. But then the documentarians came calling: “They wanted to make a film about my life. With their encouragement and support, I made a trip to Amsterdam.” (In the film, that trip begins at the 46:23 mark.)

Seeing the very same Van Goghs he’d copied countless many times before, Zhao encountered more “delicate brushstrokes and subdued colors” than he’d ever noticed before, among other physical signs that Van Gogh “must have been trying different things all the time.” After getting back to China, he found that his experience in Amsterdam had motivated him to paint not Van Gogh’s work but his own. “My wife had been with me for so many years, and we’d painted for so long, but she didn’t have a painting of herself, Zhou writes. “The first original painting I did was of my wife.” The future of Dafen may be in doubt, but Zhou’s commitment to art certainly isn’t.

Related content:

Meet Notorious Art Forger Han Van Meegeren, Who Fooled the Nazis with His Counterfeit Vermeers

What Happens When a Cheap Ikea Print Gets Presented as Fine Art in a Museum

Illustrations for a Chinese Lord of the Rings in a Stunning “Glass Painting Style”

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...The First Work of Science Fiction: Read Lucian’s 2nd-Century Space Travelogue A True Story

Late in life, Kingsley Amis declared that he would henceforth read only novels opening with the sentence “A shot rang out.” On one level, this would have sounded bizarre coming from one of Britain’s most prominent men of letters. But on another it aligned with his long-demonstrated appreciation of genre fiction, including not just stories of crime but also of high technology and space exploration. His lifelong interest in the latter inspired the Christian Gauss Lectures he delivered at Princeton in 1958, published soon thereafter as New Maps of Hell: A Survey of Science Fiction, a book that sees him trace the history of the genre well back beyond his own boyhood — about eighteen centuries beyond it.

“Histories of science fiction, as opposed to ‘imaginative literature,’ usually begin, not with Plato or The Birds of Aristophanes or the Odyssey, but with a work of the late Greek prose romancer Lucian of Samosata,” Amis writes. He refers to what scholars now know as A True Story (Ἀληθῆ διηγήματα), a novella-length fiction of the second century that has everything from space travel to interplanetary war to technology so advanced — as no less a sci-fi luminary than Arthur C. Clarke would put it much later — as to be indistinguishable from magic. At its core a work of fantastical satire, A True Story “deliberately piles extravagance upon extravagance for comic effect” in a rather un-science-fiction-like manner.

“Leaving aside the question whether there was enough science around in the second century to make science fiction feasible,” Amis writes, “I will merely remark that the sprightliness and sophistication of the True History” — as he knew the work — “make it read like a joke at the expense of nearly all early-modern science fiction, that written between, say, 1910 and 1940,” which he himself would have grown up reading.

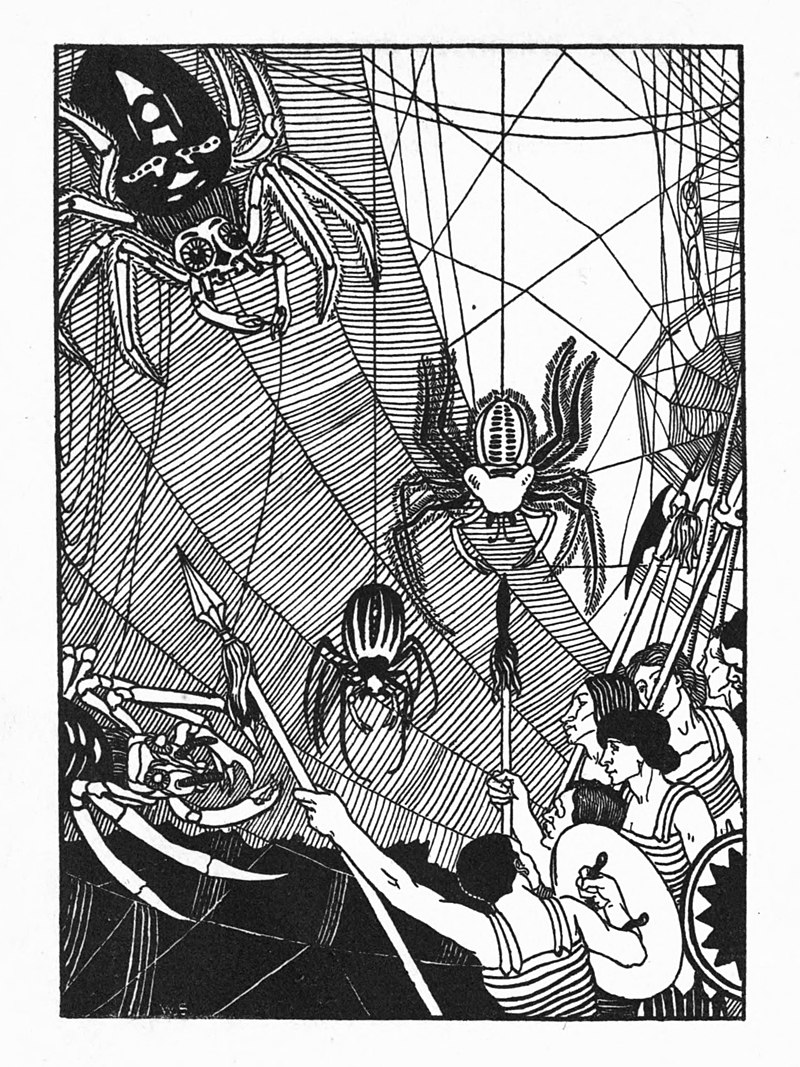

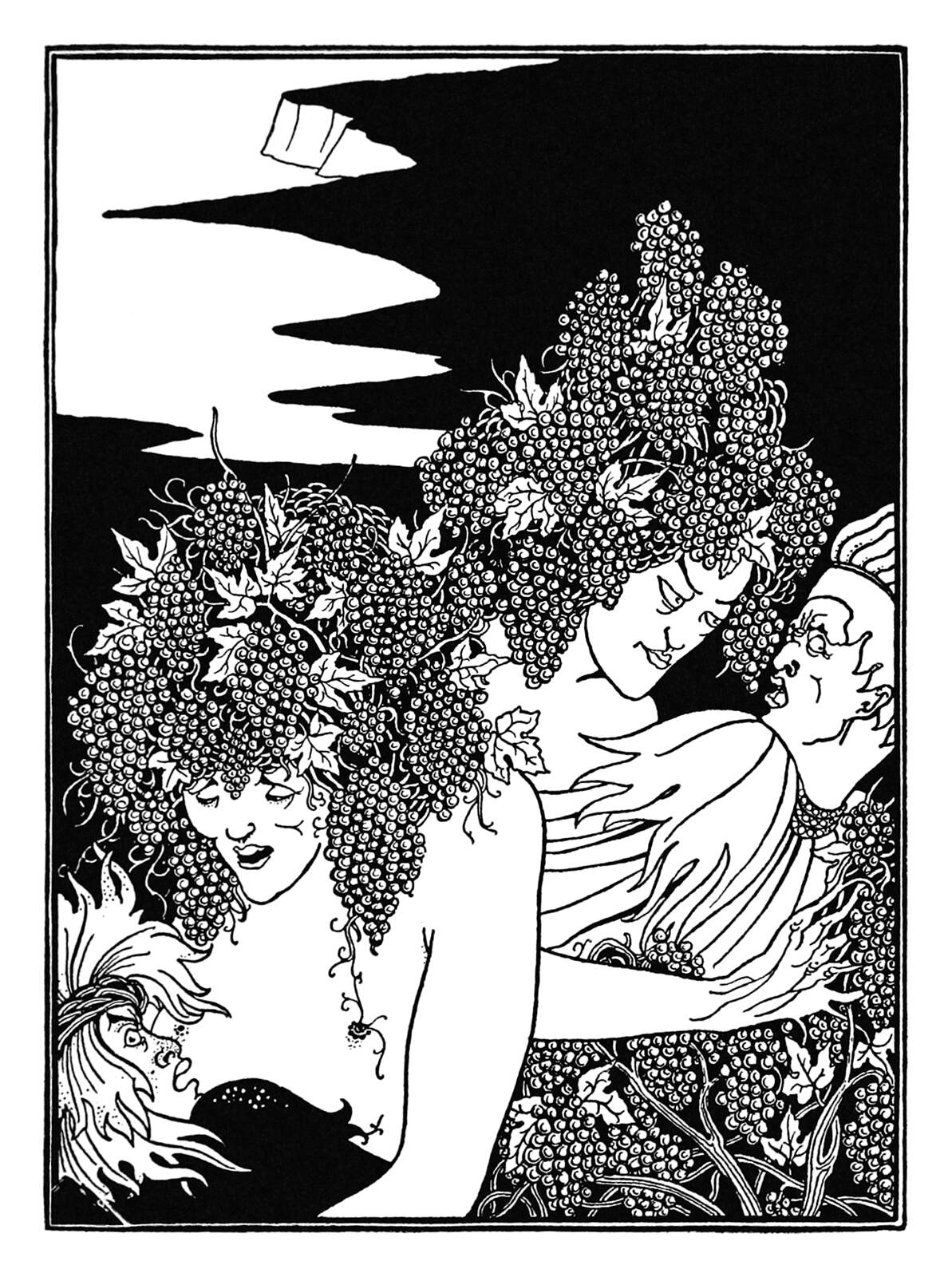

In the video by at the top of the post, filmmaker Gregory Austin McConnell summarizes Lucian’s entire travelogue, not neglecting to mention the river of wine, the tree-shaped women, the cities on the moon, the army of the sun, the battlefield-spinning space spiders, the dogs who ride on winged acorns, the floating sentient lamps, and the 187 and ½ mile-long whale.

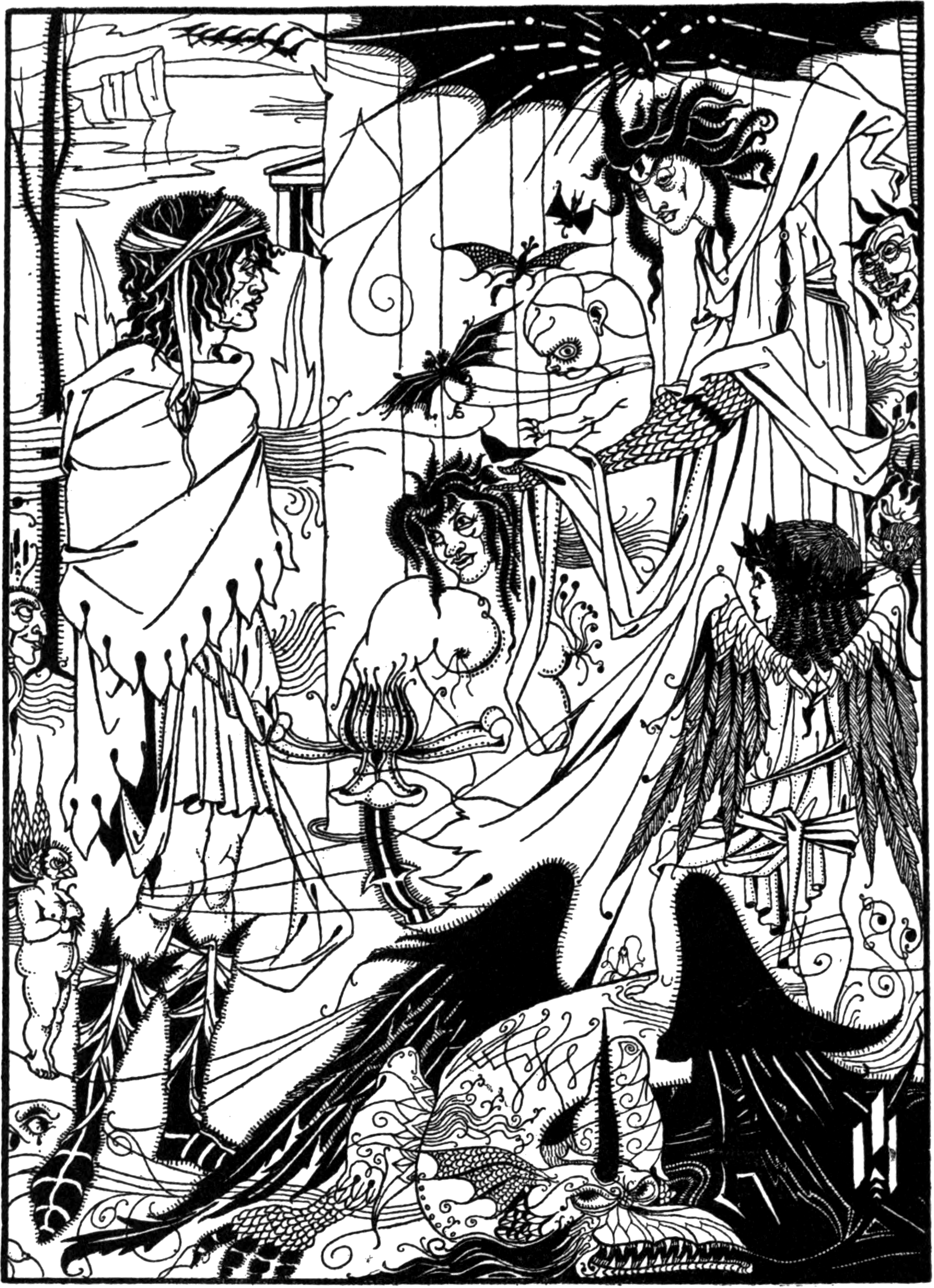

This clearly isn’t what we’d now call “hard” science fiction. So how, exactly, to label it? Such arguments erupt over every major work of genre fiction, even from antiquity. A True Story contains elements of what would become comedy sci-fi, military sci-fi, and even the fantasy-and-sci-fi-hybridizing “space opera” most popularly exemplified by Star Wars and its many sequels. Categorization quibbles aside, what matters about any work in the broader tradition of “speculative fiction” is whether it fires up the reader’s imagination, and Lucian’s work has done it for not just ancients but moderns like the 19th-century artists William Strang and Aubrey Beardsley, whose illustrations from 1894 editions of A True Story appear above. Now that “science fiction rules the cinematic landscape,” as McConnell puts it, who will adapt it for us postmoderns?

Related content:

When Astronomer Johannes Kepler Wrote the First Work of Science Fiction, The Dream (1609)

Mythos: An Animation Retells Timeless Greek Myths with Abstract Modern Designs

The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction: 17,500 Entries on All Things Sci-Fi Are Now Free Online

Isaac Asimov Recalls the Golden Age of Science Fiction (1937–1950)

Free Science Fiction Classics Available on the Web

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Watch Hilarious Spoofs of Classic Film Genres: Film Noir, Spaghetti Westerns, Scandinavian Crime Dramas, Time Travel Films & More

Comedian Alasdair Beckett-King has a keen ear for entertainment tropes and subscribes to the belief that “putting too much effort into things makes them funnier.”

The result is a series of one-minute videos in which he spoofs the conventions of a particular genre or long running series, with perfect visuals, meta dialogue, and faithfully rendered performance styles.

Beckett-King put his London Film School training to use with this project during lockdown, spending “absolutely ages putting together something very tiny.”

Witness his take on every episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation, in which the captain of the ship, a Patrick Stewart doppelgänger and “vegetarian space socialist who is always right” negotiates with a “representative of a kind of iffy alien race not necessarily based on a specific human ethnicity.” As Beckett-King told Eric Johnson, host of Follow Friday podcast:

That one was very, very hard work because I had to do a CGI bald cap for myself because I have long, long flowing hair. I had to try and do an impression of Captain Picard of the Starship Enterprise… it’s not that good. There’s so much work that went into it.

Before I posted it, I was convinced I’d wasted my time. Then luckily it did quite well and people really liked it. People kept saying, “When are you doing Captain Picard again?” I’m like, “I’m not! because it took ages to do the bald head, and you’ve seen it now.” I think what’s nice about it though, is you get to try something, commit to it and then see if it’s funny afterwards. It’s quite like doing live standup.

(Beckett-King’s partner Rachel Anne Smith gets credits for the non-CGI costumes.)

Some other favorites:

Every Single Scandinavian Crime Drama: The killer could be anyone in Helgasund. That’s over seven people.

Every Single Spooky Podcast: The frozen soil was littered with what appeared to be discarded Casper mattresses and Bombas socks.

Every Single Spaghetti Western: Yeah, well your lips don’t synch…

Every Haunted House Movie: It’s the perfect place for me to quit drinking, finish my novel, and really come to terms with that deer we hit on the way over.

Every Episode of Popular Time Travel Show: Help us, Doctor. The intransigent Implacablons are poised to destroy us.

How Every Film Noir Ends: Talk your way out of a snub nosed pistol held at waist height.

Should you find yourself at loose ends, waiting for the next Beckett-King “every single…” episode to drop, try biding your time with his Art House Movie Spoilers and North East of England spin on Jaws.

Buy a Coffee for Alasdair Beckett-King here.

Related Content:

Download a Complete, Cover-to-Cover Parody of The New Yorker: 80 Pages of Fine Satire

The Time When National Lampoon Parodied Mad Magazine: A Satire of Satire (1971)

Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primaologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

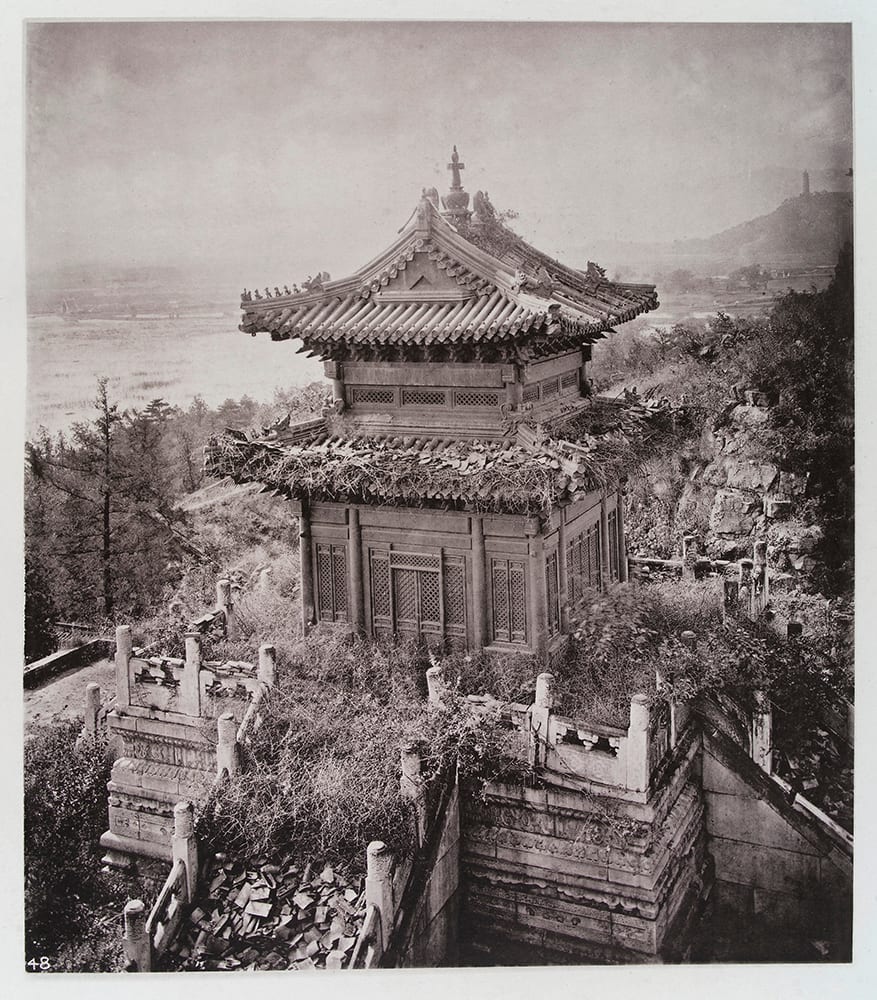

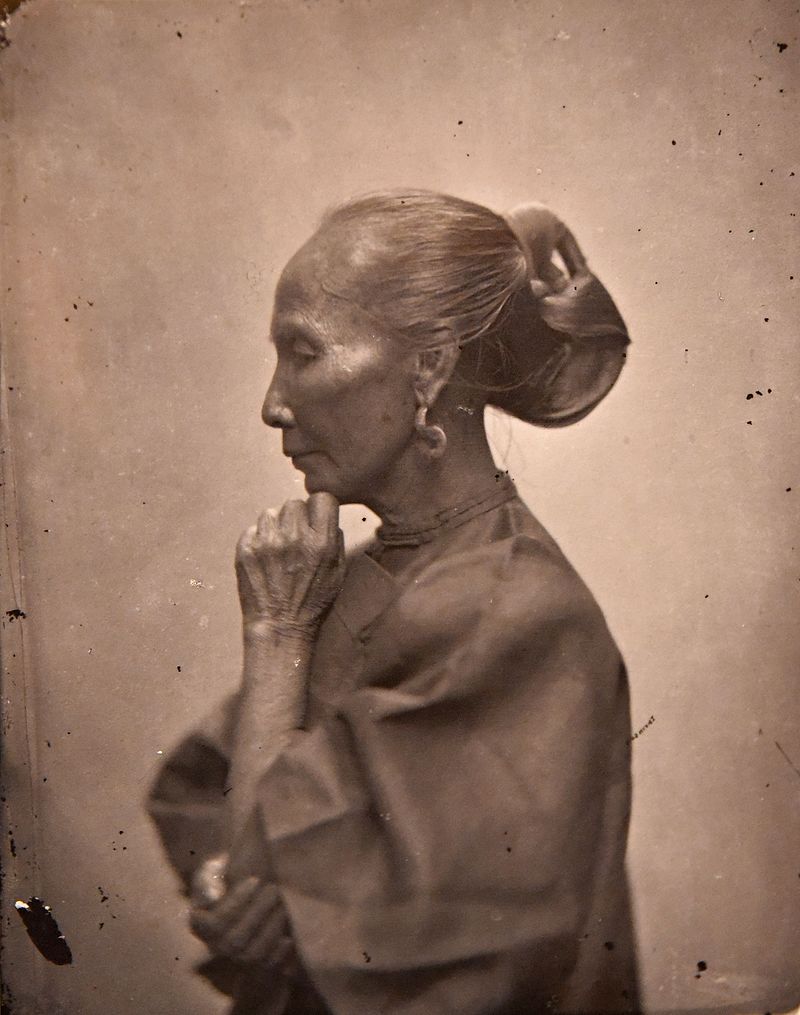

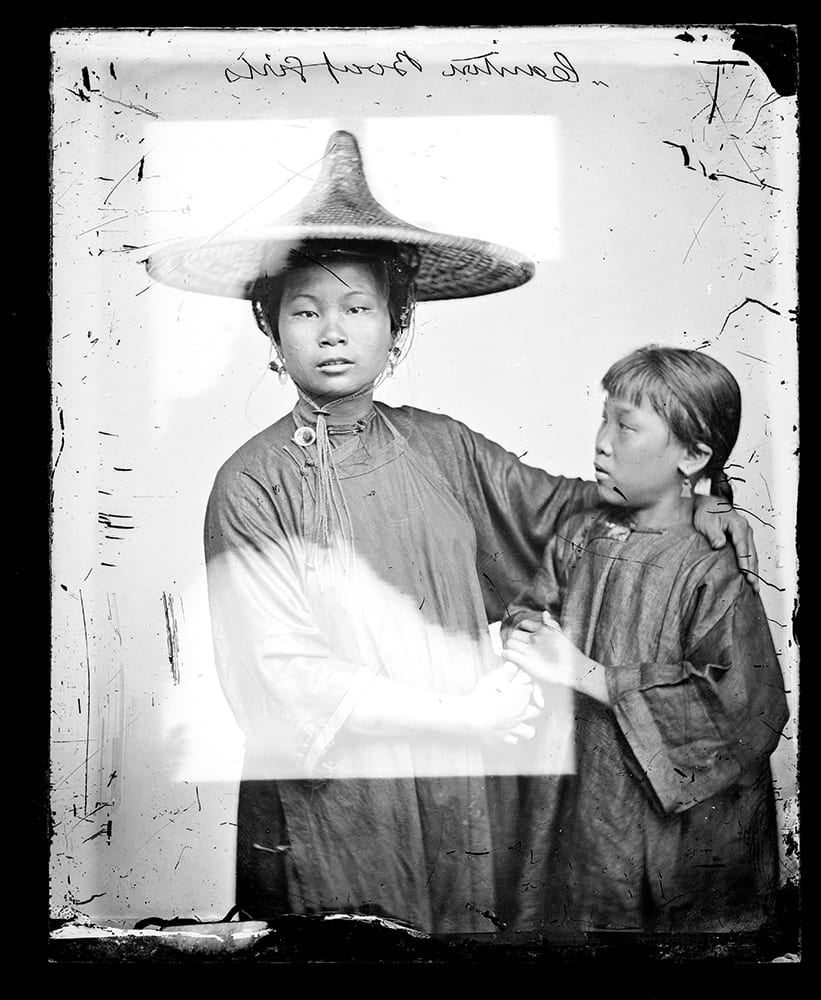

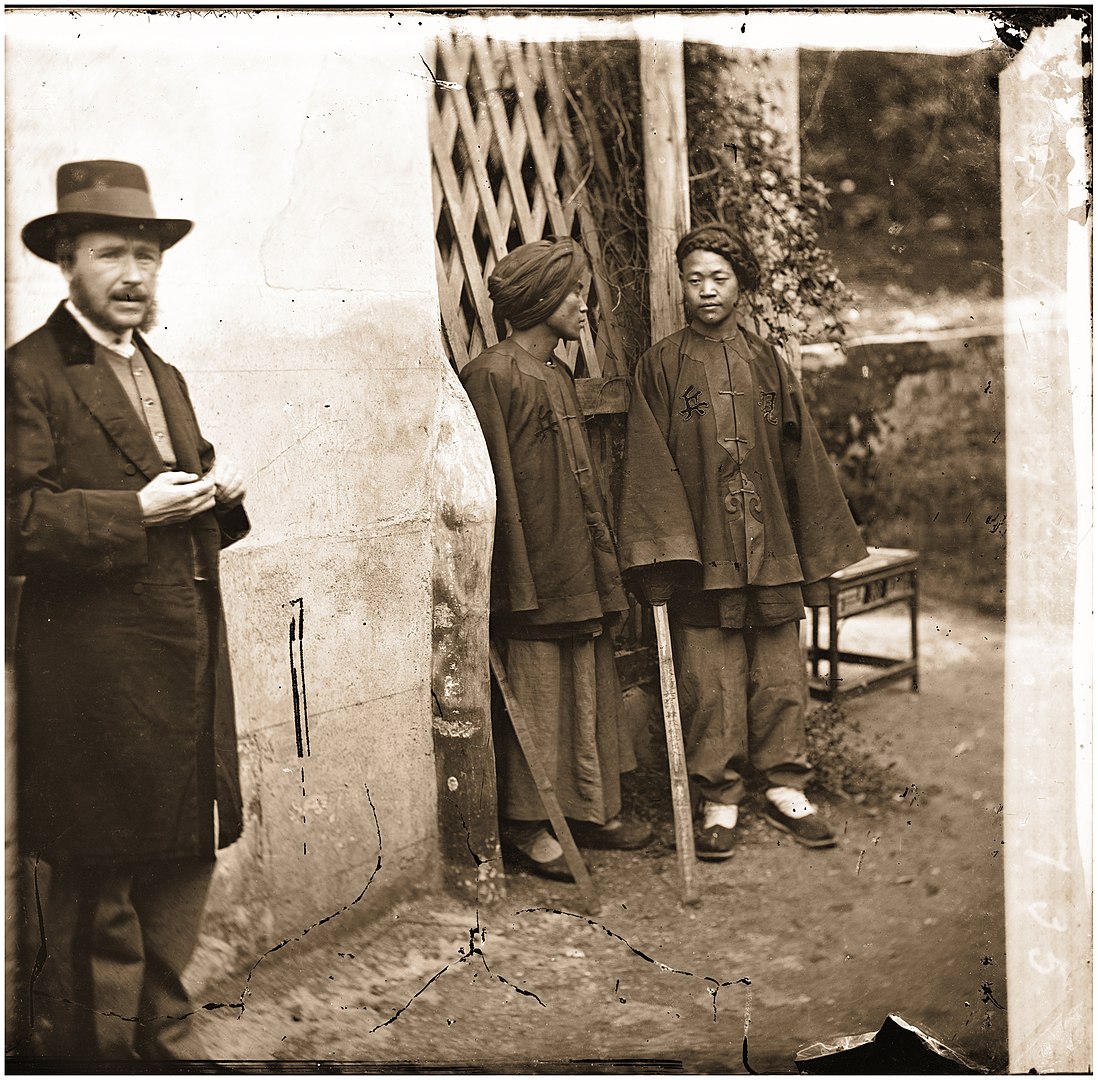

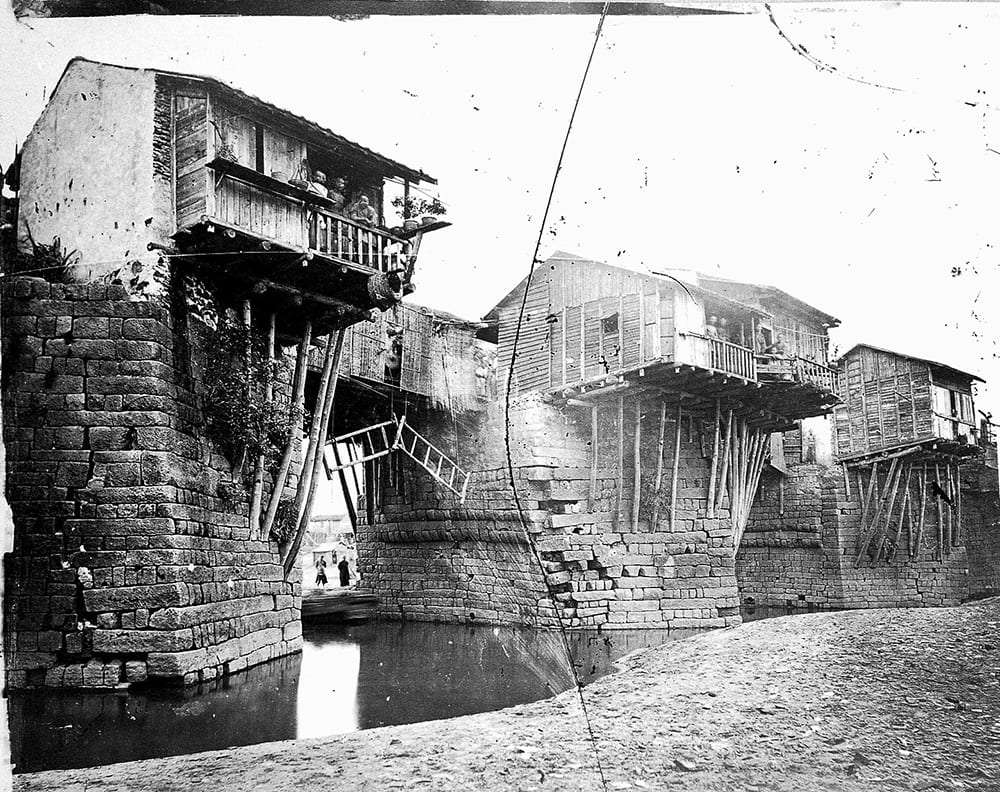

Read More...Behold the Photographs of John Thomson, the First Western Photographer to Travel Widely Through China (1870s)

In the early 1860s, a few Westerners had seen China — but nearly all of them had seen it for themselves. The still-new medium of photography had yet to make images of everywhere available to viewers everywhere else, which meant an opportunity for traveling practitioners like John Thomson. “The son of a tobacco spinner and shopkeeper,” says BBC.com, ” he was apprenticed to an Edinburgh optical and scientific instrument manufacturer where he learned the basics of photography.”

In 1862 Thomson sailed from Leith “with a camera and a portable dark room. He set up in Singapore before exploring the ancient civilizations of China, Thailand — then known as Siam — and Cambodia.” It is for his extensive photography of China in the late 1860s and early 1870s that he’s best known today.

First lavishly published in a series of books titled Illustrations of China and Its People (now available to read free online at the Yale University Library: volume one, volume two, volume three, volume four), they now constitute some of the earliest and richest direct visual records of Chinese landscapes, cityscapes, and society as they were in the late 19th century.

“The first Western photographer to travel widely through the length and breadth of China,” Thomson brought his camera on journeys “far more extensive than those undertaken by most Westerners of his generation,” extending “beyond the relative comfort and safety of the coastal treaty ports.” Those words come from scholar of the 19th-century Allen Hockley, whose five-part visual essay “John Thomson’s China” at MIT Visualizing Cultures provides a detailed overview and historical contextualization of Thomson’s work in Asia.

Thomson’s photographs, writes Hockley, “fall into two broad categories: scenic views and types. Views encompassed both natural landscapes and built environments. They could be panoramic, taking in large swaths of scenery, or they might highlight specific natural phenomena or individual structures.”

Types “focused on the manners and customs of Chinese people and tended to highlight the defining features of gender, age, class, ethnicity, and occupation.” A century and a half later, both Thomson’s views and types have given scholars in a variety of disciplines much to discuss.

“It is clear from his commentary to Illustrations of China that, however sympathetic he was towards Chinese people, he could often be superior and high-handed,” writes Andrew Hiller at Visualizing China. “If Thomson never sought to question the validity of Britain’s presence, his attitude towards China was ambivalent. Whilst critical of what he saw as the corruption and obfuscation of Qing officials, he nevertheless could see the country’s potential.”

Thomson also helped others to see that potential — or at least those who could afford to buy his books, whose prices matched the quality of their production. But today, thanks to online archives like Historical Photographs of China and Wellcome Collection, they’re free for everyone to behold. China itself has become much more accessible since Thomson’s day, of course, but it’s famously a much different place than it was 25 years ago, let alone 150 years ago. The land through which he traveled — and of which he took so many of the very earliest photographs — is now infinitely less accessible to us than it ever was to his fellow Westerners of the 19th century.

Hear a lecture on Thomson’s photography in China from the University of London here.

Related Content:

How Vividly Colorized Photos Helped Introduce Japan to the World in the 19th Century

1850s Japan Comes to Life in 3D, Color Photos: See the Stereoscopic Photography of T. Enami

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Watch Anthony Bourdain’s First Food-and-Travel Series A Cook’s Tour Free Online (2002–03)

At the time of his death in 2018, Anthony Bourdain was quite possibly the most famous cook in the world. Without question he held the title of the most famous cook-traveler, a status resting primarily on No Reservations and Parts Unknown, the television shows he hosted on the Travel Chanel and CNN, respectively. But it all began with A Cook’s Tour, which the Food Network originally broadcast in 2002 and 2003. That series, Bourdain’s very first, took him from Japan to Morocco to Mexico to Australia to Thailand — and through many points in between — in search of the world’s most stimulating eating experiences.

Now A Cook’s Tour has come available free to watch on Youtube, thanks to the streaming channel GoTraveler (who also offer the show through their own service).

A Portuguese slaughtering-and-roasting party; vodka-fueled ice fishing in St. Petersburg; an exploration of the American “Barbecue Triangle” constituted by Kansas City, Houston, and North Carolina; and a best-faith effort to lose himself in Chiang Mai: if you caught these or other of Bourdain’s early international culinary adventures those nearly twenty years ago, you can relive them, and if you missed out, you can enjoy them for the first time.

During the launch phase of his rise to fame (after decades of restaurant work and years of writing, an effort that first produced a couple of food-themed murder-mystery novels), Bourdain managed to tap into a new wave of gastronomic interest then rising in America. He did so with a street-smart sense of humor that appealed even to viewers with no particular investment in the world of cooking and dining, as long as they had an interest in the world itself. With A Cook’s Tour, he took food television out of the kitchen — way out of the kitchen — and over the eighteen years since its conclusion, the series’ influence has become so pervasive as almost to be invisible. Anthony Bourdain may be gone, but parts of his personality live on in every high-profile traveler out there cooking, eating, and getting lost today.

Related Content:

Anthony Bourdain Talks About the Big Break That Changed His Life — at Age 44

Al Jazeera Travel Show Explores World Cities Through Their Street Food

Watch 26 Free Episodes of Jacques Pépin’s TV Show, More Fast Food My Way

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Watch The True History Of The Traveling Wilburys, a Free Film Documenting the Making of the 1980s Super Group

“It really had very little to do with combining a bunch of famous people,” says Tom Petty about the Traveling Wilburys. “It was a bunch of friends that just happened to be really good at making music.”

One of the most modest supergroups of the 20th century, one that fate and chance threw together for a very brief period, the Traveling Wilburys made music that sits outside the usual histories of 1980s music, featuring five men in different states of their careers. Tom Petty was about to have a comeback, George Harrison had just had one, Jeff Lynne was no longer having chart hits as ELO, but he was shaping the sound of the late 1980s as a producer, Roy Orbison was *about* to have a posthumous comeback, and Bob Dylan was…doing whatever Dylan does—every album he put out in the ‘80s had an equal number of detractors and comeback claimants. Put it this way: the Traveling Wilburys didn’t feel like a nostalgia act, and neither did it feel like a marketing idea. It was actually lightning in a bottle.

“It was George’s band,” Lynne says in the above mini documentary, but it wasn’t really formed as one. It just sort of *evolved*.

As he explains early in the doc, Harrison was having dinner with Roy Orbison and Jeff Lynne and invited them along to a studio in Los Angeles the next day. He had the hankering to make a tune, and they wound up using Bob Dylan’s home studio—the normally reclusive Dylan actually picked up the phone on the first ring and gave the okay. And Harrison’s guitar was over at Tom Petty’s house, so he came along as well. The song they recorded that day was “Handle with Care,” which fell together like magic. (Dylan provided the title after looking over at a cardboard box).

Harrison sat on the song for a while, having no idea what to do with it. The only thing he could do, was to record nine more songs and call it an album. Which, once they had found time in everybody’s schedule, they did. The songs were recorded at the home studio of Dave Stewart (of the Eurythmics) and finalized back in London with Harrison and Lynne. The group gave themselves the assignment of one song written and recorded per day. That the record isn’t a mish-mash of jamming, leftover ideas, and covers, and instead has a legitimate amount of classic singles and career-highlight moments is a testament to the friendship between the five (and drummer Jim Keltner, who knew them all).

Friends indeed, but it doesn’t mean they weren’t also big fans of each other. What’s cool to watch in the doc is how in awe they all seem: George is amazed by Bob’s cryptic scrawled lyrics and his ability to nail a song on essentially the first take. Tom Petty is in awe of George’s democratic ways with choosing who gets to sing one of the songs, regardless of who wrote it—really, how do you follow Roy Orbison’s version of a song? But Tom Petty still had a go.

The album maintains that friendly vibe in the recording: microphones were mobile to catch music wherever it happened. Jim Keltner played rhythm on the inside of the kitchen’s refrigerator. Songs were written in the kitchen. And after the work was done, the music would continue. “A lot of ukuleles till dawn,” says Harrison.

Roy Orbison only made it into the first music video off of the album, “Handle With Care.” He passed away just after the album went platinum in 1988, and appears as an empty rocking chair on the next video, “The End of the Line.”

The four remaining Wilburys would reunite for one more album (jokingly titled Volume 3 by prankster Harrison), but the first album still sounds timeless, five friends just having a good time together.

The True History Of The Traveling Wilburys will be added to our collection of Free Documentaries, a subset of our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Related Content:

The Story of WHER, America’s Pioneering, First All-Woman Radio Station (1955)

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the Notes from the Shed podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, and/or watch his films here.

Read More...