Image by Kenneth Zirkel, via Wikimedia Commons

There have been many theories of how human history works. Some, like German thinker G.W.F. Hegel, have thought of progress as inevitable. Others have embraced a more static view, full of “Great Men” and an immutable natural order. Then we have the counter-Enlightenment thinker Giambattista Vico. The 18th century Neapolitan philosopher took human irrationalism seriously, and wrote about our tendency to rely on myth and metaphor rather than reason or nature. Vico’s most “revolutionary move,” wrote Isaiah Berlin, “is to have denied the doctrine of a timeless natural law” that could be “known in principle to any man, at any time, anywhere.”

Vico’s theory of history included inevitable periods of decline (and heavily influenced the historical thinking of James Joyce and Friedrich Nietzsche). He describes his concept “most colorfully,” writes Alexander Bertland at the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, “when he gives this axiom”:

Men first felt necessity then look for utility, next attend to comfort, still later amuse themselves with pleasure, thence grow dissolute in luxury, and finally go mad and waste their substance.

The description may remind us of Shakespeare’s “Seven Ages of Man.” But for Vico, Bertland notes, every decline heralds a new beginning. History is “presented clearly as a circular motion in which nations rise and fall… over and over again.”

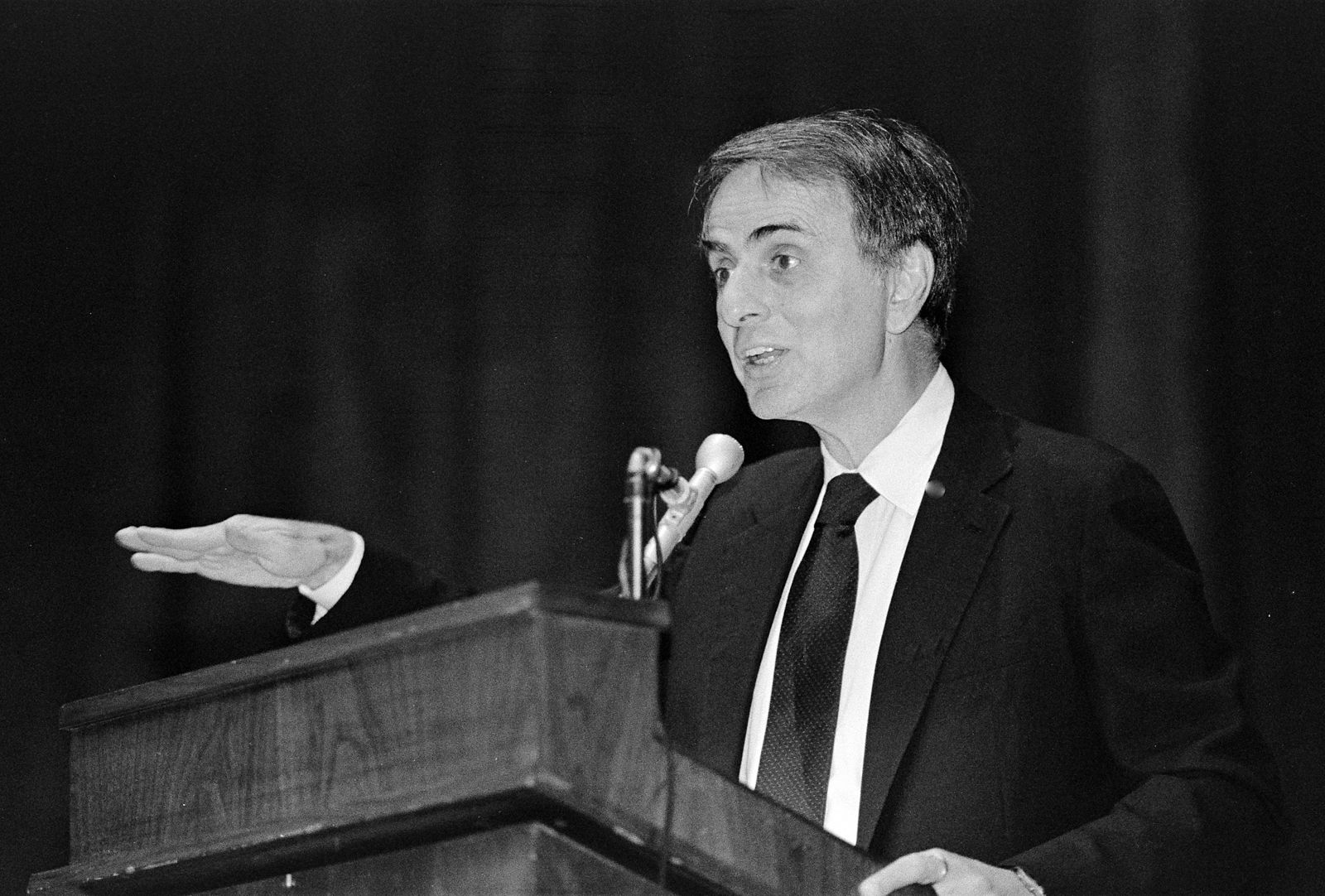

Two-hundred and twenty years after Vico’s 1774 death, Carl Sagan—another thinker who took human irrationalism seriously—published his book The Demon Haunted World, showing how much our everyday thinking derives from metaphor, mythology, and superstition. He also foresaw a future in which his nation, the U.S., would fall into a period of terrible decline:

I have a foreboding of an America in my children’s or grandchildren’s time — when the United States is a service and information economy; when nearly all the manufacturing industries have slipped away to other countries; when awesome technological powers are in the hands of a very few, and no one representing the public interest can even grasp the issues; when the people have lost the ability to set their own agendas or knowledgeably question those in authority; when, clutching our crystals and nervously consulting our horoscopes, our critical faculties in decline, unable to distinguish between what feels good and what’s true, we slide, almost without noticing, back into superstition and darkness…

Sagan believed in progress and, unlike Vico, thought that “timeless natural law” is discoverable with the tools of science. And yet, he feared “the candle in the dark” of science would be snuffed out by “the dumbing down of America…”

…most evident in the slow decay of substantive content in the enormously influential media, the 30 second sound bites (now down to 10 seconds or less), lowest common denominator programming, credulous presentations on pseudoscience and superstition, but especially a kind of celebration of ignorance…

Sagan died in 1996, a year after he wrote these words. No doubt he would have seen the fine art of distracting and misinforming people through social media as a late, perhaps terminal, sign of the demise of scientific thinking. His passionate advocacy for science education stemmed from his conviction that we must and can reverse the downward trend.

As he says in the poetic excerpt from Cosmos above, “I believe our future depends powerfully on how well we understand this cosmos in which we float like a mote of dust in the morning sky.”

When Sagan refers to “our” understanding of science, he does not mean, as he says above, a “very few” technocrats, academics, and research scientists. Sagan invested so much effort in popular books and television because he believed that all of us needed to use the tools of science: “a way of thinking,” not just “a body of knowledge.” Without scientific thinking, we cannot grasp the most important issues we all jointly face.

We’ve arranged a civilization in which most crucial elements profoundly depend on science and technology. We have also arranged things so that almost no one understands science and technology. This is a prescription for disaster. We might get away with it for a while, but sooner or later this combustible mixture of ignorance and power is going to blow up in our faces.

Sagan’s 1995 predictions are now being heralded as prophetic. As Director of Public Radio International’s Science Friday, Charles Bergquist tweeted, “Carl Sagan had either a time machine or a crystal ball.” Matt Novak cautions against falling back into superstitious thinking in our praise of Demon Haunted World. After all, he says, “the ‘accuracy’ of predictions is often a Rorschach test” and “some of Sagan’s concerns” in other parts of the book “sound rather quaint.”

Of course Sagan couldn’t predict the future, but he did have a very informed, rigorous understanding of the issues of thirty years ago, and his prediction extrapolates from trends that have only continued to deepen. If the tools of science education—like most of the country’s wealth—end up the sole property of an elite, the rest of us will fall back into a state of gross ignorance, “superstition and darkness.” Whether we might come back around again to progress, as Giambattista Vico thought, is a matter of sheer conjecture. But perhaps there’s still time to reverse the trend before the worst arrives. As Novak writes, “here’s hoping Sagan, one of the smartest people of the 20th century, was wrong.”

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2017.

Related Content:

Carl Sagan Presents His “Baloney Detection Kit”: 8 Tools for Skeptical Thinking

Carl Sagan Issues a Chilling Warning to America in His Last Interview (1996)

Philosopher Richard Rorty Chillingly Predicts the Results of the 2016 Election … Back in 1998

Carl Sagan Warns Congress about Climate Change (1985)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness