Image by Sasha Kargaltsev via Wikimedia Commons

As every cinephile has by now heard, and lamented, we’ve just lost a great American filmmaker. From Eraserhead to Blue Velvet to Mulholland Drive to Inland Empire, David Lynch’s features will surely continue to bewilder and inspire generation after generation of aspiring young auteurs. (There seems even to be a re-evaluation underway of his adaptation of Dune, the box-office catastrophe that turned him away from the Hollywood machine.) But Lynch was never exactly an aspiring young auteur himself. He actually began his career as a painter, just one of the many facets of his artistic existence that we’ve featured over the years here at Open Culture.

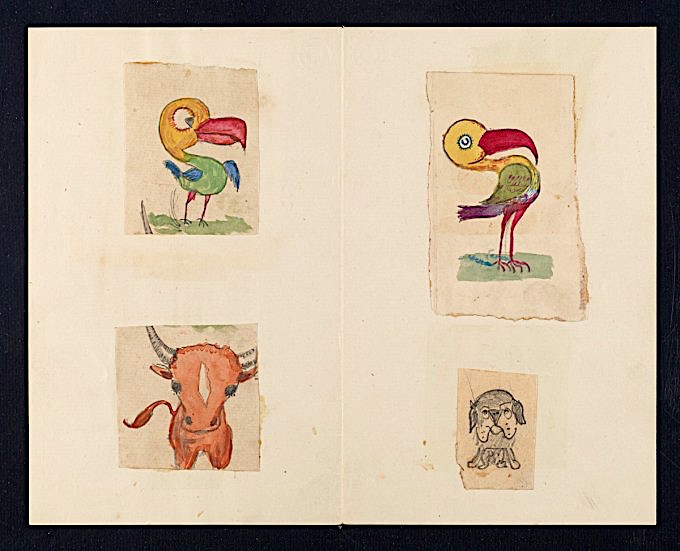

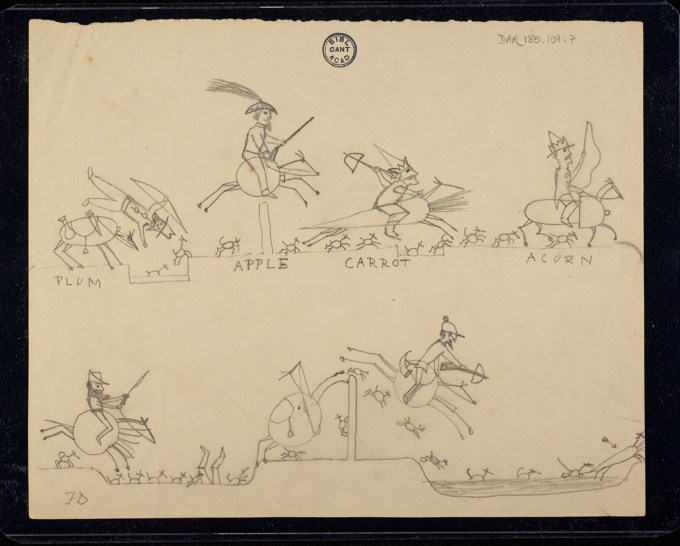

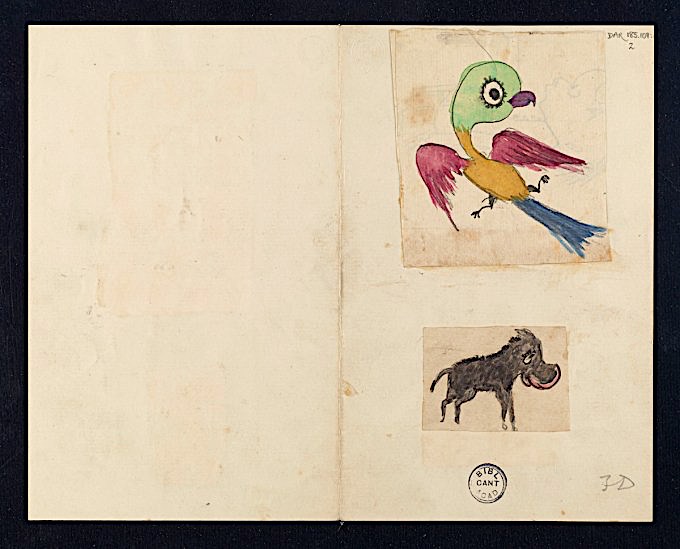

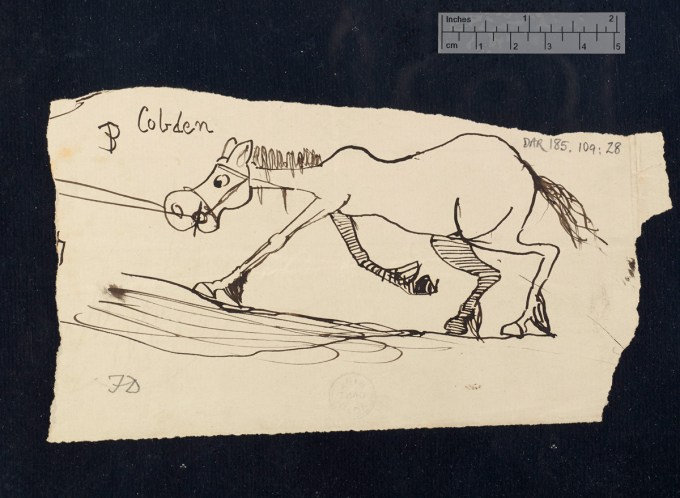

Lynch studied painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in the mid-nineteen-sixties, and the urban decay of Philadelphia at the time did a great deal to inspire the aesthetic of Eraserhead, which made his name on the midnight-movie circuit a decade later. When the MTV era fired up in just a few years, he found his signature blend of grotesquerie and hyper-normality — what would soon be termed “Lynchian” — in demand from certain like-minded recording artists. It was around that same time that he launched a side career as a comic artist, or in any case a comic writer, contributing a thoroughly static yet compellingly varied strip called The Angriest Dog in the World to the LA Reader from the early eighties through the early nineties.

In 1987, the year after the art-house blockbuster that was Blue Velvet set off what Guy Maddin later called “the last real earthquake in American cinema,” Lynch hosted a BBC television series on the history of surrealist film. That ultra-mass medium would turn out to be a surprisingly receptive venue for his highly idiosyncratic art: first he made commercials, then he co-created with Mark Frost the ABC mystery series Twin Peaks, which practically overtook American popular culture when it debuted in 1990. (See also these video essays on the making and meaning of the show.) Not that the phenomenon was limited to the U.S., as evidenced by Lynch’s going on to direct a mini-season of Twin Peaks in the form of canned-coffee commercials for the Japanese market.

Even Mulholland Drive, the picture many consider to be Lynch’s masterpiece, was conceived as a pilot for a TV show. Not long after its release, he put out more work in serial form, including the savage cartoon Dumbland and the harrowing sitcom homage Rabbits (later incorporated into Inland Empire, his final film). In the late two-thousands, he presented Interview Project, a documentary web series co-created by his son; in the early twenty-tens, he put out his first (but not last) solo music album, Crazy Clown Time. That same decade, his photographs of old factories went on display, his line of organic coffee came onto the market, his autobiography was published, and his MasterClass went online.

Lynch remained prolific through the COVID-19 pandemic of the twenty-twenties, in part by posting Los Angeles weather reports from his home to his YouTube channel. In recent years, he announced that he would never retire, despite living with a case of emphysema so severe that he could no longer direct in any conventional manner. Such are the wages, as he acknowledged, of having smoked since age seven, though he also seemed to believe that every habit and choice in life contributed to his work. Perhaps the smoking did its part to inspire him, like his long practice of Transcendental Meditation or his daily milkshake at Bob’s Big Boy, about all of which he spoke openly in life. But if there’s any particular secret of his formidable creativity, it feels as if he’s taken it with him.

Related Content:

Twin Peaks Actually Explained: A 4‑Hour Video Essay Demystifies It All

David Lynch Teaches You to Cook His Quinoa Recipe in a Strange, Surrealist Video

David Lynch Being a Madman for a Relentless 8 Minutes and 30 Seconds

David Lynch Muses About the Magic of Cinema & Meditation in a New Abstract Short Film

David Lynch Tries to Make a List of the Good Things Happening in the World … and Comes Up Blank

Angelo Badalamenti Reveals How He and David Lynch Composed the Twin Peaks’ “Love Theme”

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.