Top 10 Alternative Christmas Movie Lists: Horror, Action, Comedy & More

Die Hard is a Christmas movie. That once-contrarian categorization has increasingly been accepted over the past couple of decades, at least since an editor with whom I’ve often worked first declared it in a Slate roundup. As a result, John McTiernan’s sturdy piece of one-building eighties Hollywood action may have displaced It’s a Wonderful Life as a holiday home-video tradition in certain households. But it’s also stoked a broader desire for ever more alternative Christmas movies with subtle, even subversive holiday elements. If you, too, can’t handle yet another viewing of Miracle on 34th Street, A Christmas Story, or Home Alone this year, have a look at the top ten lists compiled in these four videos, which offer a selection of films beyond — sometimes well beyond — the established seasonal canon.

These selections come from a variety of genres, including the superhero picture: if you haven’t seen Batman Returns in a few decades, you may have forgotten how thoroughly Tim Burton saturates it with Christmas imagery, albeit of a kind suited to the dank, menacing Gotham City. Those who want to crank up the darkness further still would do well to put on the Canadian sorority-house slasher film Black Christmas, which also appears on more than one of these lists.

Joe Dante’s Yuletide-set Gremlins contains much higher-budget spectacles of destruction, albeit comedic ones; the humor of Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, another elaborate mid-eighties auteur project, runs to the dystopian, a sensibility certainly present in the holiday season itself, if seldom treated with such grotesque vividness.

The work of no single professional makes these alternative Christmas movie lists more often than Shane Black, the writer of Lethal Weapon (with Die Hard, the makings of a holiday double bill if ever there was one) and The Long Kiss Goodnight, as well as the writer-director of Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, Iron Man 3, and The Nice Guys. That all of those pictures are set at Christmastime makes them feel — no matter how heightened, fantastical, or visual effects-saturated they may be — palpably connected to our own reality. It also tends to intensify the drama: as Black remarked in one interview, “Christmas represents a little stutter in the march of days, a hush in which we have a chance to assess and retrospect our lives.” Which hardly means, of course, that it can’t be entertaining.

Related Content:

Watch Santa Claus, the Earliest Movie About Santa in Existence (1898)

Watch The Insects’ Christmas from 1913: A Stop Motion Film Starring a Cast of Dead Bugs

An Animated Christmas Fable by Maurice Sendak (1977)

Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut, the Most Troubling Christmas Film Ever Made

Blue Christmas: A Criterion Video Essay

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.

Read More...Why Overconfidence Is Our Most Dangerous Cognitive Bias

In the two-thousands, the magician-comedians Penn and Teller hosted a television series called Bullshit! In it, they took on a variety of cultural phenomena they regarded as worthy of the titular epithet, from ESP to Area 51, exorcism to creationism, feng shui to haute cuisine. Their sardonic arguments were enriched by clips of assorted interviewees —speaking in defense of the topic of the day. Penn once addressed the viewers, saying that we might wonder why anyone agrees to come on the show, given how they must know it will make them come off. But everyone, he explained, confidently believes that their own ideas are the correct ones.

That episode came right to mind while watching the new Veritasium video above, which deals with the phenomenon of overconfidence. Like the oft-cited 93 percent of Americans who believe themselves better drivers than the median, we all fall victim to that affliction at one time or another, to one degree or another; the more interesting matter under investigation is why that should be so.

One can always point to what T. S. Eliot called “the endless struggle to think well of themselves”: wanting to believe that we know it all, we take pains to present ourselves as if we do. But as explained by the professors interviewed here, Carnegie Mellon’s Baruch Fischhoff and Berkeley’s Don A. Moore (author of Perfectly Confident: How to Calibrate Your Decisions Wisely), the research has also revealed other potential factors in play.

One important candidate is, as ever, stupidity. Much has been made of the Dunning-Kruger effect, previously featured here on Open Culture, which holds that the less competent people are at a task, the more confident they tend to be about their ability to perform it. That would seem to accord with much of our everyday experience, but we should also consider the role played by the basic cognitive limitations that apply to us all. Our brains can only process so much at once, and when they come up against capacity, they default to simplified, and often too-simplified, versions of the problem before them. It all becomes more difficult if we’re insulated from direct, objective feedback, a condition that often results from the kind of success and esteem that can be achieved by projecting — you guessed it — confidence.

Related content:

Why Incompetent People Think They’re Competent: The Dunning-Kruger Effect, Explained

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.

Read More...AC/DC Plays a Short Gig at CBGB in 1977: Hear Metal Being Played on Punk’s Hallowed Grounds

Punk rock and heavy metal were two genres that evolved over the ‘70s, but seemed to run parallel to each other, despite sharing common fashion, sounds, and attitudes. But then there are moments in history, where everybody plays together in the same sandbox. For example, the above remastered audio, which captures the Australian band AC/DC on their first American tour, playing New York’s CBGB, synonymous now with punk and new wave music.

The date is August 24, 1977, and AC/DC were on a cross-country trip that had taken in both club dates and arenas, where they supported—yes, hard to believe, I know—REO Speedwagon. Their album Let There Be Rock had just dropped in June. The band would be in the States until the winter.

This CBGB gig finds them on the same bill as Talking Heads and the Dead Boys, according to a poster from the time. And while there’s no video for this show, you can find a few photos that document the concert here. You can feel the muggy New York summer in these photos, but also the excitement of an unforgettable gig.

At 15 minutes, the set is short, but still three minutes longer than the Ramones’ first set at the same club three years earlier. That’s pretty metal, man.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2016.

Related Content:

Listen to Patti Smith’s Glorious Three Hour Farewell to CBGB’s on Its Final Night

The Talking Heads Play CBGB, the New York Club That Shaped Their Sound (1975)

Watch an Episode of TV-CBGB, the First Rock ‘n’ Roll Sitcom Ever Aired on Cable TV (1981)

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts.

Read More...A 400-Year-Old Ring that Unfolds to Track the Movements of the Heavens

Rings with a discreet dual purpose have been in use since before the common era, when Hannibal, facing extradition, allegedly ingested the poison he kept secreted behind a gemstone on his finger. (More recently, poison rings gave rise to a popular Game of Thrones fan theory…)

Victorians prevented their most closely kept secrets—illicit love letters, perhaps? Last wills and testaments?—from falling into the wrong hands by wearing the keys to the boxes containing these items concealed in signet rings and other statement-type pieces.

A tiny concealed blade could be lethal on the finger of a skilled (and no doubt, beautiful) assassin. These days, they might be used to collect a bit of one’s attacker’s DNA.

Enter the fictional world of James Bond, and you’ll find a number of handy dandy spy rings including one that doubles as a camera, and another capable of shattering bulletproof glass with a single twist.

Armillary sphere rings like the ones in the British Museum’s collection and the Swedish Historical Museum (top) serve a more benign purpose. Folded together, the two-part outer hoop and three interior hoops give the illusion of a simple gold band. Slipped off the wearer’s finger, they can fan out into a physical model of celestial longitude and latitude.

Art historian Jessica Stewart writes that in the 17th century, rings such as the above specimen were “used by astronomers to study and make calculations. These pieces of jewelry were considered tokens of knowledge. Inscriptions or zodiac symbols were often used as decorative elements on the bands.”

The armillary sphere rings in the British Museum’s collection are made of a soft high-alloy gold.

Jewelry-loving modern astronomers seeking an old school finger-based calculation tool that really works can order armillary sphere rings from Brooklyn-based designer Black Adept.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

When Astronomer Johannes Kepler Wrote the First Work of Science Fiction, The Dream (1609)

The Rembrandt Book Bracelet: Behold a Functional Bracelet Featuring 1400 Rembrandt Drawings

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist in New York City.

Read More...Musician Plays the Last Stradivarius Guitar in the World, the “Sabionari” Made in 1679

Last night, while the home team lost the big game on TVs at a local dive bar, my noisy rock band opened for a chamber pop ensemble. Electric guitars and feedback gave way to classical acoustics, violin, piano, accordion, and even a saw. It was an interesting cultural juxtaposition in an evening of cultural juxtapositions. The sports and music didn’t gel, but an odd symmetry emerged from the two bands’ contrasting styles, to a degree. The instrument above, on the other hand, would have fit right in with the second act, whose old world charm would surely find a place for a 1679 guitar—one crafted by the legendary master luthier Antonio Stradivari, no less.

If you know nothing at all about music or musical instruments, you know the name Stradivari and the violins that bear his name. They are such coveted, valuable objects they sometimes appear as the target of crime capers in the movies and on television. This Stradivarius guitar, called the “Sabionari,” is even rarer than the violins. The Stradivari family, writes Forgotten Guitar, “produced over 1000 instruments, of which 960 were violins.” Yet, “a small number of guitars were also crafted, and as of today only one remains playable.” Highly playable, you’ll observe in these videos, thanks to the restoration by luthiers Daniel Sinier, Francoise de Ridder, and Lorenzo Frignani.

In the clip just above, Baroque concert guitarist Rolf Lislevand plays Santiago de Murcia’s “Tarantela” on the restored guitar, whose sonorous ringing timbre recalls another Baroque instrument, the harpsichord.

So unique and unusual is the ten-string Stradivarius Sabionari that it has its own website, where you’ll find many detailed, close-up photos of the elegant design as well as more music, like the piece above, Angelo Michele Bartolotti’s Suite in G Minor as performed by classical guitarist Krishnasol Jiménez, who, along with Lislevand, has been entrusted with the instrument for many live performances. Owned by a private collector, the Sabionari very often appears at lectures on restoration and conservation of classical instruments, as well as in performances around Europe. You’ll find on sabionari.com many more videos of the guitar in action (like that below of guitarist Ugo Nastrucci improvising), links to exhibits, descriptions of the challengingly long neck and Baroque tuning, and a sense of just how much the Sabionari gets around for such a rare, antique instrument.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2016.

Related Content:

Why Violins Have F‑Holes: The Science & History of a Remarkable Renaissance Design

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC.

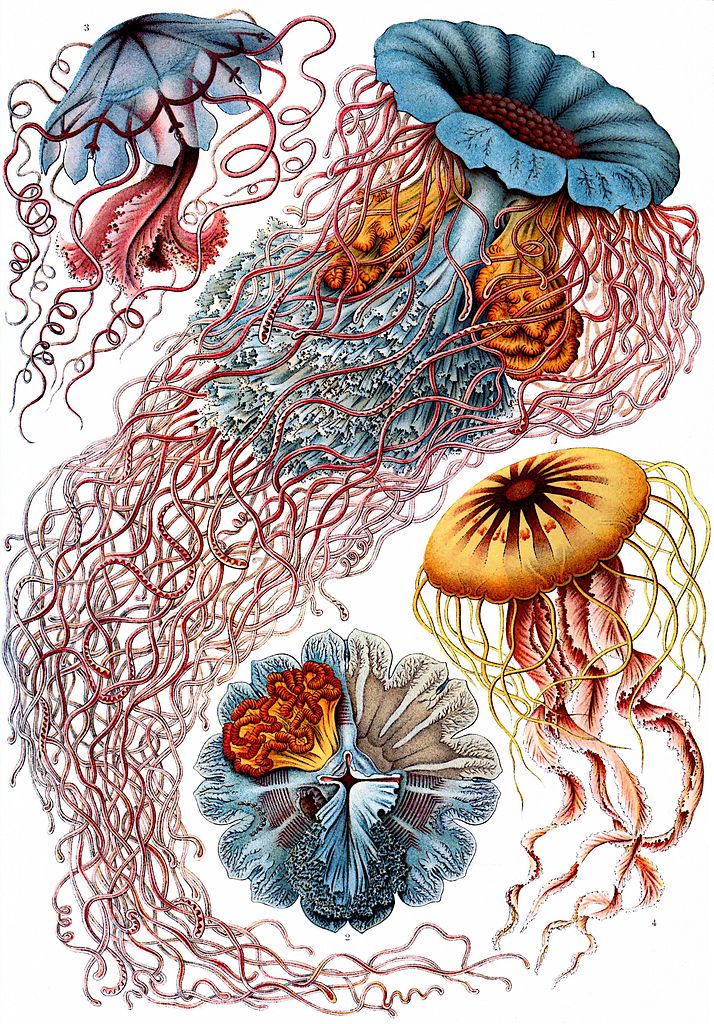

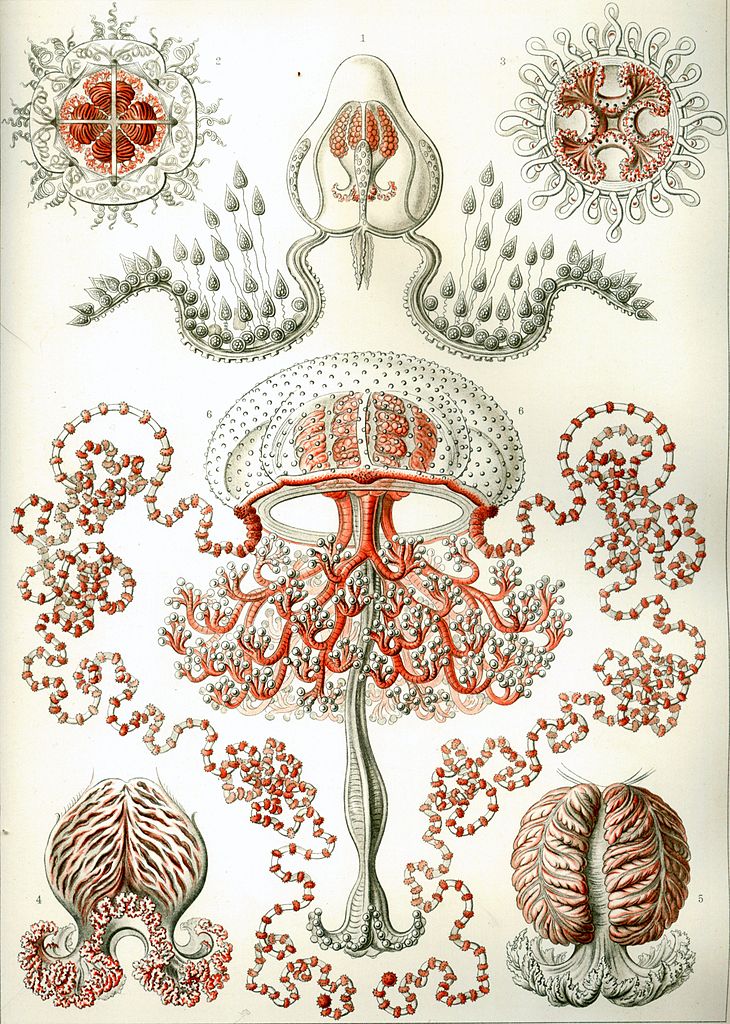

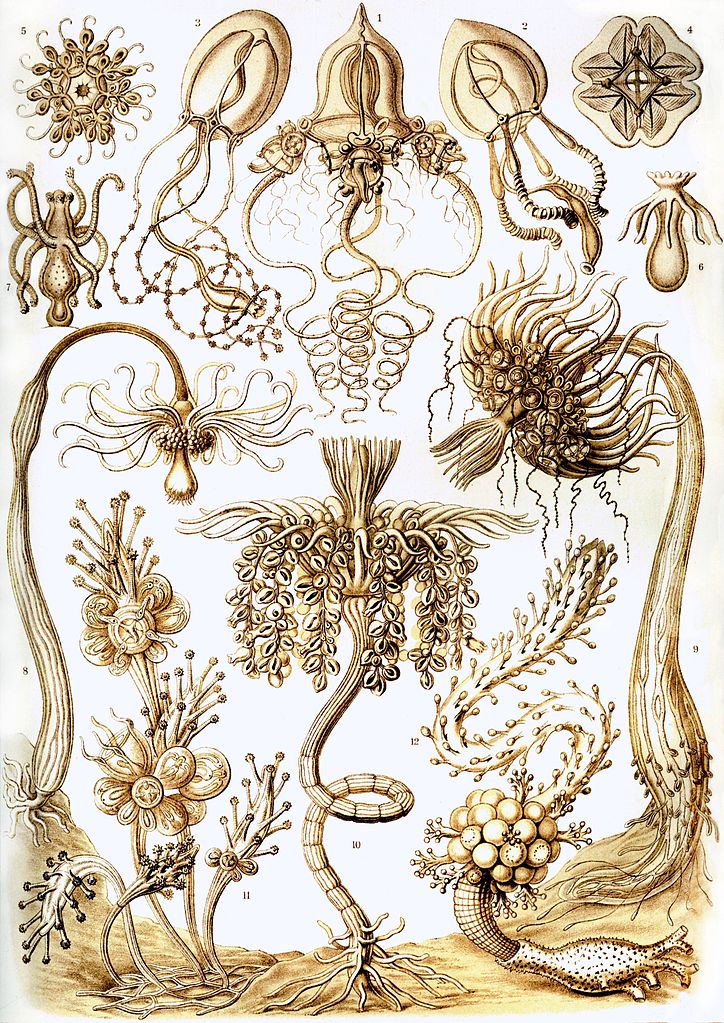

Read More...Ernst Haeckel’s Sublime Drawings of Flora & Fauna: The Beautiful Scientific Drawings That Influenced Europe’s Art Nouveau Movement (1889)

If you follow the ongoing beef many popular scientists have with philosophy, you’d be forgiven for thinking the two disciplines have nothing to say to each other. That’s a sadly false impression, though they have become almost entirely separate professional institutions. But during the first, say, 200 years of modern science, scientists were “natural philosophers”—often as well versed in logic, metaphysics, or theology as they were in mathematics and taxonomies. And most of them were artists too of one kind or another. Scientists had to learn to draw in order to illustrate their findings before mass-produced photography and computer imaging could do it for them. Many scientists have been fine artists indeed, rivaling the greats, and they’ve made very fine musicians as well.

And then there’s Ernst Heinrich Haeckel, a German biologist and naturalist, philosopher and physician, and proponent of Darwinism who described and named thousands of species, mapped them on a genealogical tree, and “coined several scientific terms commonly known today,” This is Colossal writes, “such as ecology, phylum, and stem cell.” That’s an impressive resume, isn’t it? Oh, and check out his art—his brilliantly colored, elegantly rendered, highly stylized depictions of “far flung flora and fauna,” of microbes and natural patterns, in designs that inspired the Art Nouveau movement. “Each organism Haeckel drew has an almost abstract form,” notes Katherine Schwab at Fast Co. Design, “as if it’s a whimsical fantasy he dreamed up rather than a real creature he examined under a microscope. His drawings of sponges reveal their intensely geometric structure—they look architectural, like feats of engineering.”

Haeckel published 100 fabulous prints beginning in 1889 in a series of ten books called Kunstformen der Natur (“Art Forms in Nature”), collected in two volumes in 1904. The astonishing work was “not just a book of illustrations but also the summation of his view of the world,” one which embraced the new science of Darwinian evolution wholeheartedly, writes scholar Olaf Breidbach in his 2006 Visions of Nature.

Haeckel’s method was a holistic one, in which art, science, and philosophy were complementary approaches to the same subject. He “sought to secure the attention of those with an interest in the beauties of nature,” writes professor of zoology Rainer Willmann in a book from Taschen called The Art and Science of Ernst Haeckel, “and to emphasize, through this rare instance of the interplay of science and aesthetics, the proximity of these two realms.”

The gorgeous Taschen book includes 450 of Haeckel’s drawings, watercolors, and sketches, spread across 704 pages, and it’s expensive. But you can see all 100 of Haeckel’s originally published prints in zoomable high-resolution scans here. Or purchase a one-volume reprint of the original Art Forms in Nature, with its 100 glorious prints, through this Dover publication, which describes Haeckel’s art as “having caused the acceptance of Darwinism in Europe…. Today, although no one is greatly interested in Haeckel the biologist-philosopher, his work is increasingly prized for something he himself would probably have considered secondary.” It’s a shame his scientific legacy lies neglected, if that’s so, but it surely lives on through his art, which may be just as needed now to illustrate the wonders of evolutionary biology and the natural world as it was in Haeckel’s time.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2017.

Related Content

Download 435 High Resolution Images from John J. Audubon’s The Birds of America

Two Million Wondrous Nature Illustrations Put Online by The Biodiversity Heritage Library

Cats in Japanese Woodblock Prints: How Japan’s Favorite Animals Came to Star in Its Popular Art

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Revisit One of the Most Polarizing Albums in Rock History: Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music, Which Came Out 50 Years Ago

Fifty years ago this month, Lou Reed nearly destroyed his own career with one double album. Metal Machine Music sold 100,000 copies during the three weeks of summer 1975 between its release and its removal from the market. More than a few of the many buyers who promptly returned it would have been expecting something like Sally Can’t Dance, Reed’s solo album from the previous year, whose slickly produced songs went down easier than anything he’d recorded with the Velvet Underground. What they heard when they put the new album on their turntables (or inserted the Quadrophonic 8‑track tape into their decks) was “nothing, absolutely nothing but screaming feedback noise recorded at various frequencies, played back against various other noise layers, split down the middle into two totally separate channels of utterly inhuman shrieks and hisses.”

That description comes from voluble Creem rock critic and avowed enthusiast of decadence Lester Bangs, who also happened to be one of Metal Machine Music’s most fervent defenders. At one point he declared it “the greatest record ever made in the history of the human eardrum.” (“Number Two: Kiss Alive!”)

Much of what we know about the intentions behind this baffling album come from Bangs’ writings, including those that purport to transcribe conversations with Reed himself, who’d been one of the critic’s readiest verbal sparring partners. The inspiration, as Reed explained to Bangs, came from listening to composers Iannis Xenakis and La Monte Young, who dared to go beyond the boundaries of what most listeners would consider music at all. Reed also insisted that he’d deliberately inserted bits and pieces of Mozart, Beethoven, and other classical masters into his sonic maelstrom, though Bangs clearly didn’t buy it.

“Metal Machine Music doesn’t seem so weird now, does it?” asked an interviewer on Night Flight just a decade or so after the album’s release. “No, it doesn’t, does it?” Reed says. “In light of Eno and all this stuff that came out now, it’s not nearly as insane and crazy as they said it was then.” Indeed, it sounds almost of a piece with an influential work of ambient music like Brian Eno’s Music for Airports, though that album was meant to calm its listeners rather than drive them from the room. Over the half-century since its release, Metal Machine Music has accrued enough appreciation to be paid tributes like the live performances by German ensemble Zeitkratzer that have continued long after Reed’s death. The legacy of his “electronic instrumental composition,” as he said after one such concert in 2007, also includes a namesake clause in recording contracts stipulating that “the artist must turn in a record that sound like the artist that the record company signed — not come in with Metal Machine Music.”

Related content:

Teenage Lou Reed Sings Doo-Wop Music (1958–1962)

Hear Ornette Coleman Collaborate with Lou Reed, Which Lou Called “One of My Greatest Moments”

David Bowie and Lou Reed Perform Live Together for the First and Last Time: 1972 and 1997

Lou Reed Creates a List of the 10 Best Records of All Time

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.

Read More...How to Enter a ‘Flow State’ on Command: Peak Performance Mind Hack Explained in 7 Minutes

You can be forgiven for thinking the concept of “flow” was cooked up and popularized by yoga teachers. That word gets a lot of play when one is moving from Downward-Facing Dog on through Warrior One and Two.

Actually, flow — the state of “effortless effort” — was coined by Goethe, from the German “rausch”, a dizzying sort of ecstasy.

Friedrich Nietzsche and psychologist William James both considered the flow state in depth, but social theorist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, author of Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention, is the true giant in the field. Here’s one of his definitions of flow:

Being completely involved in an activity for its own sake. The ego falls away. Time flies. Every action, movement, and thought follows inevitably from the previous one, like playing jazz. Your whole being is involved, and you’re using your skills to the utmost.

Author Steven Kotler, Executive Director of the Flow Research Collective, not only seems to spend a lot of time thinking about flow, as a leading expert on human performance, he inhabits the state on a fairly regular basis, too.

Chalk it up to good luck?

Good genes? (Some researchers, including retired NIH geneticist Dean Hamer and psychologist C. Robert Cloninger, think genetics play a part…)

As Kotler points out above, anyone can hedge their bets by clearing away distractions — all the usual baddies that interfere with sleep, performance, or productivity.

It’s also important to know thyself. Kotler’s an early bird, who gets crackin’ well before sunrise:

I don’t just open my eyes at 4:00 AM, I try to go from bed to desk before my brain even kicks out of its Alpha wave state. I don’t check any emails. I turn everything off at the end of the day including unplugging my phones and all that stuff so that the next morning there’s nobody jumping into my inbox or assaulting me emotionally with something, you know what I mean?… I really protect that early morning time.

By contrast, his night owl wife doesn’t start clearing the cobwebs ’til early evening.

In the above video for Big Think, Kotler notes that 22 flow triggers have been discovered, pre-conditions that keep attention focused in the present moment.

His website lists many of those triggers:

- Complete Concentration in the Present Moment

- Immediate Feedback

- Clear Goals

- The Challenge-Skills Ratio (ie: the challenge should seem slightly out of reach

- High consequences

- Deep Embodiment

- Rich Environment

- Creativity (specifically, pattern recognition, or the linking together of new ideas)

Kotler also shares University of North Carolina psychologist Keith Sawyer’s trigger list for groups hoping to flow like a well-oiled machine:

- Shared Goals

- Close Listening

- “Yes And” (additive, rather than combative conversations)

- Complete Concentration (total focus in the right here, right now)

- A sense of control (each member of the group feels in control, but still)

- Blending Egos (each person can submerge their ego needs into the group’s)

- Equal Participation (skills levels are roughly and equal everyone is involved)

- Familiarity (people know one another and understand their tics and tendencies)

- Constant Communication (a group version of immediate feedback)

- Shared, Group Risk

One might think people in the flow state would be floating around with an expression of ecstatic bliss on their faces. Not so, according to Kotler. Rather, they tend to frown slightly. Good news for anyone with resting bitch face!

(We’ll thank you to refer to it as resting flow state face from here on out.)

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2022.

Related Content

How to Get into a Creative “Flow State”: A Short Masterclass

David Lynch Explains How Simple Daily Habits Enhance His Creativity

“The Philosophy of “Flow”: A Brief Introduction to Taoism

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...Who Really Built the Egyptian Pyramids—And How Did They Do It?

Although it’s certainly more plausible than hypotheses like ancient aliens or lizard people, the idea that slaves built the Egyptian pyramids is no more true. It derives from creative readings of Old Testament stories and technicolor Cecil B. Demille spectacles, and was a classic whataboutism used by slavery apologists. The notion has “plagued Egyptian scholars for centuries,” writes Eric Betz at Discover. But, he adds emphatically, “Slaves did not build the pyramids.” Who did?

The evidence suggests they were built by a force of skilled laborers, as the Veritasium video above explains. These were cadres of elite construction workers who were well-fed and housed during their stint. “Many Egyptologists,” including archaeologist Mark Lehner, who has excavated a city of workers in Giza, “subscribe to the hypotheses that the pyramids were… built by a rotating labor force in a modular, team-based kind of organization,” Jonathan Shaw writes at Harvard Magazine. Graffiti discovered at the site identifies team names like “Friends of Khufu” and “Drunkards of Menkaure.”

The excavation also uncovered “tremendous quantities of cattle, sheep, and goat bone, ‘enough to feed several thousand people, even if they ate meat every day,’ adds Lehner,” suggesting that workers were “fed like royalty.” Another excavation by Lehner’s friend Zahi Hawass, famed Egyptian archaeologist and expert on the Great Pyramid, has found worker cemeteries at the foot of the pyramids, meaning that those who perished were buried in a place of honor. This was incredibly hazardous work, and the people who undertook it were celebrated and recognized for their achievement.

Laborers were also working off an obligation, something every Egyptian owed to those above them and, ultimately, to their pharaoh. But it was not a monetary debt. Lehner describes what ancient Egyptians called bak, a kind of feudal duty. While there were slaves in Egypt, the builders of the pyramids were maybe more like the Amish, he says, performing the same kind of obligatory communal labor as a barn raising. In that context, when we look at the Great Pyramid, “you have to say ‘This is a hell of a barn!’’’

The evidence unearthed by Lehner, Hawass, and others has “dealt a serious blow to the Hollywood version of a pyramid building,” writes Shaw, “with Charlton Heston as Moses intoning, ‘Pharaoh, let my people go!’” Recent archeology has also dealt a blow to extraterrestrial or time-travel explanations, which begin with the assumption that ancient Egyptians could not have possessed the know-how and skill to build such structures over 4,000 years ago. Not so. Veritasium explains the incredible feats of moving the outer stones without wheels and transporting the granite core of the pyramids 620 miles from its quarry to Giza.

Ancient Egyptians could plot directions on the compass, though they had no compasses. They could make right angles and levels and thus had the technology required to design the pyramids. What about digging up the Great Pyramid’s 2 million blocks of yellow limestone? As we know, this was done by a skilled workforce, who quarried an “Olympic swimming-pool’s worth of stone every eight days” for 23 years to build the Great Pyramid, notes Joe Hanson in the PBS It’s Okay to Be Smart video above. They did so using the only metal available to them, copper.

This may sound incredible, but modern experiments have shown that this amount of stone could be quarried and moved, using the technology available, by a team of 1,200 to 1,500 workers, around the same number of people archaeologists believe to have been on-site during construction. The limestone was quarried directly at the site (in fact the Sphinx was mostly dug out of the earth, rather than built atop it). How was the stone moved? Egyptologists from the University of Liverpool think they may have found the answer, a ramp with stairs and a series of holes which may have been used as a pulley system.

Learn more about the myths and the realities of the builders of Egypt’s pyramids in the It’s Okay to Be Smart “Who Built the Pyramids, Part 1″ video above.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2021.

Related Content:

What the Great Pyramids of Giza Originally Looked Like

A Walking Tour Around the Pyramids of Giza: 2 Hours in Hi Def

Take a 360° Interactive Tour Inside the Great Pyramid of Giza

Take a 3D Tour Through Ancient Giza, Including the Great Pyramids, the Sphinx & More

The Grateful Dead Play at the Egyptian Pyramids, in the Shadow of the Sphinx (1978)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...How Medieval Islamic Engineering Brought Water to the Alhambra

Between 711 and 1492, much of the Iberian Peninsula, including modern-day Spain, was under Muslim rule. Not that it was easy to hold on to the place for that length of time: after the fall of Toledo in 1085, Al-Andalus, as the territory was called, continued to lose cities over the subsequent centuries. Córdoba and Seville were reconquered practically one right after the other, in 1236 and 1248, respectively, and you can see the invasion of the first city animated in the opening scene of the Primal Space video above. “All over the land, Muslim cities were being conquered and taken over by the Christians,” says the companion article at Primal Nebula. “But amidst all of this, one city remained unconquered, Granada.”

“Thanks to its strategic position and the enormous Alhambra Palace, the city was protected,” and there the Alhambra remains today. A “thirteenth-century palatial complex that’s one of the world’s most iconic examples of Moorish architecture,” writes BBC.com’s Esme Fox, it’s also a landmark feat of engineering, boasting “one of the most sophisticated hydraulic networks in the world, able to defy gravity and raise water from the river nearly a kilometer below.”

The jewel in the crown of these elaborate waterworks is a white marble fountain that “consists of a large dish held up by twelve white mythical lions. Each beast spurts water from its mouth, feeding four channels in the patio’s marble floor that represent the four rivers of paradise, and then running throughout the palace to cool the rooms.”

The fuente de los Leones also tells time: the number of lions currently indicates the hour. This works thanks to an ingenious design explained both verbally and visually in the video. Anyone visiting the Alhambra today can admire this and other examples of medieval opulence, but travelers with an engineer’s cast of mind will appreciate even more how the palace’s builders got the water there at all. “The hill was around 200 meters above Granada’s main river,” says the narrator, which entailed an ambitious project of damming and redirection, to say nothing of the pool above the palace designed to keep the whole hydraulic system pressurized. The Alhambra’s heated baths and well-irrigated gardens represent the luxurious height of Moorish civilization, but they also remind us that, then as now, beneath every luxury lies an impressive feat of technology.

Related content:

The Brilliant Engineering That Made Venice: How a City Was Built on Water

How Toilets Worked in Ancient Rome and Medieval England

The Amazing Engineering of Roman Baths

Historic Spain in Time Lapse Film

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.

Read More...