Unlock AI’s Potential in Your Work and Daily Life: Take a Popular Course from Google

Generative AI is rapidly becoming an essential tool for streamlining work and solving complex challenges. However, knowing how to use GenAI effectively isn’t always obvious. That’s where Google Prompting Essentials comes in. This course will teach you to write clear and specific instructions—known as prompts—for AI. Once you can prompt well, you can unlock generative AI’s potential more fully.

Launched in April, Google Prompting Essentials has become the most popular GenAI course offered on Coursera. The course itself is divided into four modules. First, “Start Writing Prompts Like a Pro” will teach you a 5‑step method for crafting effective prompts. (Watch the video from Module 1 above, and more videos here.) With the second module, “Design Prompts for Everyday Work Tasks,” you will learn how to use AI to draft emails, brainstorm ideas, and summarize documents. The third module, “Speed Up Data Analysis and Presentation Building,” teaches techniques for uncovering insights in data, visualizing results, and preparing presentations. The final module, “Use AI as a Creative or Expert Partner,” explores advanced techniques such as prompt chaining and multimodal prompting. Plus, you will “create a personalized AI agent to role-play conversations and provide expert feedback.”

Offered on the Coursera platform, Google Prompting Essentials costs $49. Once you complete the course, you will receive a certificate from Google to share with your network and employer. Better yet, you will understand how to make GenAI a more useful tool in your life and work. Enroll here.

Note: Open Culture has a partnership with Coursera. If readers enroll in certain Coursera courses and programs, it helps support Open Culture.

Read More...Solving a 2,500-Year-Old Puzzle: How a Cambridge Student Cracked an Ancient Sanskrit Code

If you find yourself grappling with an intellectual problem that’s gone unsolved for millennia, try taking a few months off and spending them on activities like swimming and meditating. That very strategy worked for a Cambridge PhD student named Rishi Rajpopat, who, after a summer of non-research-related activities, returned to a text by the ancient grammarian, logician, and “father of linguistics” Pāṇini and found it newly comprehensible. The rules of its composition had stumped scholars for 2,500 years, but, as Rajpopat tells it in an article by Tom Almeroth-Williams at Cambridge’s website, “Within minutes, as I turned the pages, these patterns started emerging, and it all started to make sense.”

Pāṇini composed his texts using a kind of algorithm: “Feed in the base and suffix of a word and it should turn them into grammatically correct words and sentences through a step-by-step process,” writes Almeroth-Williams. But “often, two or more of Pāṇini’s rules are simultaneously applicable at the same step, leaving scholars to agonize over which one to choose.” Or such was the case, at least, before Rajpopat’s discovery that the difficult-to-interpret “metarule” meant to apply to such cases dictates that “between rules applicable to the left and right sides of a word respectively, Pāṇini wanted us to choose the rule applicable to the right side.”

That may not be immediately understandable to those unfamiliar with the structure of Sanskrit. Almeroth-Williams’ piece clarifies with an example using mantra, one word from the language that everybody knows. “In the sentence ‘devāḥ prasannāḥ mantraiḥ’ (‘The Gods [devāḥ] are pleased [prasannāḥ] by the mantras [mantraiḥ]’) we encounter ‘rule conflict’ when deriving mantraiḥ, ‘by the mantras,’ ” he writes. ” The derivation starts with ‘mantra + bhis.’ One rule is applicable to the left part ‘mantra’ and the other to right part ‘bhis.’ We must pick the rule applicable to the right part ‘bhis,’ which gives us the correct form ‘mantraih.’ ”

Applying this rule renders interpretations of Pāṇini’s work almost completely unambiguous and grammatical. It could even be employed, Rajpopat has noted, to teach Sanskrit grammar to computers being programmed for natural language processing. It no doubt took him a great deal of intensive study to reach the point where he was able to discover the true meaning of Pāṇini’s clarifying metarule, but it didn’t truly present itself until he let his unconscious mind take a crack at it. As we’ve said here on Open Culture before, there are good reasons we do our best thinking while doing things like walking or taking a shower, a phenomenon that philosophers have broadly recognized through the ages — and, like as not, was understood by the great Pāṇini himself.

Related content:

Learn Latin, Old English, Sanskrit, Classical Greek & Other Ancient Languages in 10 Lessons

Introduction to Indian Philosophy: A Free Online Course

How Scholars Finally Deciphered Linear B, the Oldest Preserved Form of Ancient Greek Writing

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Jimi Hendrix Arrives in London in 1966, Asks to Get Onstage with Cream, and Blows Eric Clapton Away: “You Never Told Me He Was That F‑ing Good”

Jimi Hendrix arrived on the London scene like a ton of bricks in 1966, smashing every British blues guitarist to pieces the instant they saw him play. As vocalist Terry Reid tells it, when Hendrix played his first showcase at the Bag O’Nails, arranged by Animals’ bassist Chas Chandler, “there were guitar players weeping. They had to mop the floor up. He was piling it on, solo after solo. I could see everyone’s fillings falling out. When he finished, it was silence. Nobody knew what to do. Everybody was dumbstruck, completely in shock.”

He only exaggerates a little, by all accounts, and when Reid says “everybody,” he means everybody: Keith Richards, Mick Jagger, Brian Jones, Jeff Beck, Paul McCartney, The Who, Eric Burdon, John Mayall, and maybe Jimmy Page, though he denies it. Mayall recalls, “the buzz was out before Jimi had even been seen here, so people were anticipating his performance, and he more than lived up to what we were expecting.” In fact, even before this legendary event sent nearly every star classic rock guitarist back to the woodshed, Jimi had arrived unannounced at the Regent Street Polytechnic, and asked to sit in and jam with Cream, where he proceeded to dethrone the reigning British guitar god, Eric Clapton.

Nobody knew who he was, but “in those days anybody could get up with anybody,” Clapton says in a recent interview, “if you were convincing enough that you could play. He got up and blew everyone’s mind.” As Hendrix biographer Charles Cross tells it, “no one had ever asked to jam” with Cream before. “Most would have been too intimidated by their reputation as the best band in Britain.” To hear the story as it’s told in the clip above from the BBC documentary Seven Ages of Rock, no one else would have ever dared to get onstage with Eric Clapton. Clapton, as the famed graffiti in London announced, was God. “It was a very brave person who would do that,” says Jack Bruce.

Actually, it was Chandler who asked the band, and who also tried to prepare Clapton. Jimi got onstage, plugged into Bruce’s bass amp, and played a version of Howlin’ Wolf’s “Killin’ Floor.” Everyone was “completely gobsmacked,” Clapton writes in his autobiography. “I remember thinking that here was a force to be reckoned with. It scared me, because he was clearly going to be a huge star, and just as we are finding our own speed, here was the real thing.” Fear, envy, awe… all reasonable emotions when standing next to Jimi Hendrix as he tears through “Killin’ Floor” three times faster than anyone else played it (as you can see him play it in Stockholm above)—while doing the splits, lying on the floor, playing with his teeth and behind his head…

“It was amazing,” writes Clapton, “and it was musically great, too, not just pyrotechnics.” There’s no telling how Jimi might have remembered the event had he lived to write his memoirs, but he would have been pretty modest, as was his way. No one else who saw him felt any need to hold back. “It must have been difficult for Eric to handle,” says Bruce, “because [Eric] was ‘God,’” and this unknown person comes along, and burns.” He puts it slightly differently at the top: “Eric was a guitar player. Jimi was some sort of force of nature.”

Rock journalist Keith Altham has yet a third account, as Ed Vulliamy writes at The Guardian. He remembers “Chandler going backstage after Clapton left in the middle of the song ‘which he had yet to master himself’; Clapton was furiously puffing on a cigarette and telling Chas: ‘You never told me he was that fucking good.’” Who knows if Hendrix knew Clapton had struggled with “Killin’ Floor” and decided not to try it live. But as blues guitarist Stephen Dale Petit notes, “when Chas invited Jimi to London, Jimi did not ask about money or contracts. He asked if Chas would introduce him to Beck and Clapton.”

He had come to meet, and blow away, his rock heroes. “Two weeks after The Bag O’Nails,” writes Classic Rock’s Johnny Black, “when Cream appeared at The Marquee Club, Clapton was sporting a frizzy perm and he left his guitar feeding back against the amp, just as he’d seen Jimi do.”

Related Content:

Jimi Hendrix Unplugged: Two Great Recordings of Hendrix Playing Acoustic Guitar

23-Year-Old Eric Clapton Demonstrates the Elements of His Guitar Sound (1968)

Jimi Hendrix Opens for The Monkees on a 1967 Tour; Then Flips Off the Crowd and Quits

Jimi Hendrix’s Final Interview Animated (1970)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...J. G. Ballard Demystifies Surrealist Paintings by Dalí, Magritte, de Chirico & More

Before his signature works like The Atrocity Exhibition, Crash, and High-Rise, J. G. Ballard published three apocalyptic novels, The Drowned World, The Burning World, and The Crystal World. Each of those books offers a different vision of large-scale environmental disaster, and the last even provides a clue as to its inspiration. Or rather, its original cover does, by using a section of Max Ernst’s painting The Eye of Silence. “This spinal landscape, with its frenzied rocks towering into the air above the silent swamp, has attained an organic life more real than that of the solitary nymph sitting in the foreground,” Ballard writes in “The Coming of the Unconscious,” an article on surrealism written shortly after The Crystal World appeared in 1966.

First published in an issue of the magazine New Worlds (which also contains Ballard’s take on Chris Marker’s La Jetée), the piece is ostensibly a review of Patrick Waldberg’s Surrealism and Marcel Jean’s The History of Surrealist Painting, but it ends up delivering Ballard’s short analyses of a series of paintings by various surrealist masters.

The Eye of Silence shows the landscapes of our world “for what they are — the palaces of flesh and bone that are the living facades enclosing our own subliminal consciousness.” The “terrifying structure” at the center of René Magritte’s The Annunciation is “a neuronic totem, its rounded and connected forms are a fragment of our own nervous systems, perhaps an insoluble code that contains the operating formulae for our own passage through time and space.”

In Giorgio de Chirico’s The Disquieting Muses, “an undefined anxiety has begun to spread across the deserted square. The symmetry and regularity of the arcades conceals an intense inner violence; this is the face of catatonic withdrawal”; its figures are “human beings from whom all transitional time has been eroded.” Another work depicts an empty beach as “a symbol of utter psychic alienation, of a final stasis of the soul”; its displacement of beach and sea through time “and their marriage with our own four-dimensional continuum, has warped them into the rigid and unyielding structures of our own consciousness.” There Ballard writes of no less familiar a canvas than The Persistence of Memory by Salvador Dalí, whom he called “the greatest painter of the twentieth century” more than 40 years after “The Coming of the Unconscious” in the Guardian.

A decade thereafter, that same publication’s Declan Lloyd theorizes that the experimental billboards designed by Ballard in the fifties (previously featured here on Open Culture) had been textual reinterpretations of Dalí’s imagery. Until the late sixties, Ballard says in a 1995 World Art interview, “the Surrealists were very much looked down upon. This was part of their attraction to me, because I certainly didn’t trust English critics, and anything they didn’t like seemed to me probably on the right track. I’m glad to say that my judgment has been seen to be right — and theirs wrong.” He understood the long-term value of Surrealist visions, which had seemingly been obsolesced by World War II before, “all too soon, a new set of nightmares emerged.” We can only hope he won’t be proven as prescient about the long-term habitability of the planet.

Related content:

Sci-Fi Author J.G. Ballard Predicts the Rise of Social Media (1977)

J. G. Ballard’s Experimental Text Collages: His 1958 Foray into Avant-Garde Literature

An Introduction to Surrealism: The Big Aesthetic Ideas Presented in Three Videos

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Jimi Hendrix Unplugged: Two Great Recordings of Hendrix Playing Acoustic Guitar

As a young guitar player, perhaps no one inspired me as much as Jimi Hendrix, though I never dreamed I’d attain even a fraction of his skill. But what attracted me to him was his near-total lack of formality—he didn’t read music, wasn’t trained in any classical sense, played an upside-down right-handed guitar as a lefty, and fully engaged his head and heart in every note, never pausing for an instant (so it seemed) to second-guess whether it was the right one. I knew his raw emotive playing was firmly rooted in the Delta blues, but it wasn’t until later in my musical journey that I discovered his return to more traditional form after he disbanded The Experience and formed Band of Gypsys with Billy Cox and Buddy Miles. While most of the recordings he made with them didn’t see official release, they’ve appeared since his death in compilation after boxset after compilation, including one of the most beloved of Hendrix’s blues songs, “Hear My Train A Comin’.”

Originally titled “Get My Heart Back Together” when he played it at Woodstock in 1969, the song is pure roots, with lyrics that bespeak of both Hendrix’s loneliness and his playful dreams of greatness. (“I’m gonna buy this town / And put it all in my shoe.”) Several versions of the song float around on various posthumous releases—both live and as studio outtakes (including two different takes on the excellent 1994 Blues).

But we have the rare treat, above, of seeing Hendrix play the song on a twelve-string acoustic guitar, Lead Belly’s instrument of choice. The footage comes from the 1973 documentary film Jimi Hendrix (which you can watch on YouTube for $2.99). Hendrix first plays the intro, seated alone in an all-white studio, playing folk-style with the fingers of his left hand. It is, of course, flawless, yet still he stops and asks the filmmakers for a redo. “I was scared to death,” he says, betraying the shyness and self-doubt that lurked beneath his mind-blowing ability and flamboyant persona. His playing is no less perfect when he picks up the tune again and plays it through.

Solo acoustic recordings of Hendrix—film and audio—are incredibly rare. If like me you’re a fan of Hendrix, acoustic blues, or both, this video will make you hunger for more Jimi unplugged. While Hendrix did more than anyone before him to turn guitar amps into instruments with his squalls of electric feedback and distorted wah-wah squeals, when you strip his playing down to basics, he’s still pretty much as good as it gets.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Jimi Hendrix Plays “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” Days After the Song Was Released (1967)

Behold Moebius’ Many Psychedelic Illustrations of Jimi Hendrix

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.

Read More...Learn How to Create Your Own Custom AI Assistants Using OpenAI GPTs: A Free Course from Vanderbilt University

Last fall, OpenAI started letting users create custom versions of ChatGPT–ones that would let people create AI assistants to complete tasks in their personal or professional lives. In the months that followed, some users created AI apps that could generate recipes and meals. Others developed GPTs to create logos for their businesses. You get the picture.

If you’re interested in developing your own AI assistant, Vanderbilt computer science professor Jules White has released a free online course called “OpenAI GPTs: Creating Your Own Custom AI Assistants.” On average, the course should take seven hours to complete.

Here’s how he frames the course:

This cutting-edge course will guide you through the exciting journey of creating and deploying custom GPTs that cater to diverse industries and applications. Imagine having a virtual assistant that can tackle complex legal document analysis, streamline supply chain logistics, or even assist in scientific research and hypothesis generation. The possibilities are endless! Throughout the course, you’ll delve into the intricacies of building GPTs that can use your documents to answer questions, patterns to create amazing human and AI interaction, and methods for customizing the tone of your GPTs. You’ll learn how to design and implement rigorous testing scenarios to ensure your AI assistant’s accuracy, reliability, and human-like communication abilities. Prepare to be amazed as you explore real-world examples and case studies, such as:

1. GPT for Personalized Learning and Education: Craft a virtual tutor that adapts its teaching approach based on each student’s learning style, providing personalized lesson plans, interactive exercises, and real-time feedback, transforming the educational landscape.

2. Culinary GPT: Your Personal Recipe Vault and Meal Planning Maestro. Step into a world where your culinary creations come to life with the help of an AI assistant that knows your recipes like the back of its hand. The Culinary GPT is a custom-built language model designed to revolutionize your kitchen experience, serving as a personal recipe vault and meal planning and shopping maestro.

3. GPT for Travel and Business Expense Management: A GPT that can assist with all aspects of travel planning and business expense management. It could help users book flights, hotels, and transportation while adhering to company policies and budgets. Additionally, it could streamline expense reporting and reimbursement processes, ensuring compliance and accuracy.

4. GPT for Marketing and Advertising Campaign Management: Leverage the power of custom GPTs to analyze consumer data, market trends, and campaign performance, generating targeted marketing strategies, personalized messaging, and optimizing ad placement for maximum engagement and return on investment.

You can sign up for the course at no cost here. Or, alternatively, you can elect to pay $49 and receive a certificate at the end.

As a side note, Jules White (the professor) also designed another course previously featured here on OC. It focuses on prompt engineering for ChatPGPT.

Related Content

A New Course Teaches You How to Tap the Powers of ChatGPT and Put It to Work for You

Read More...

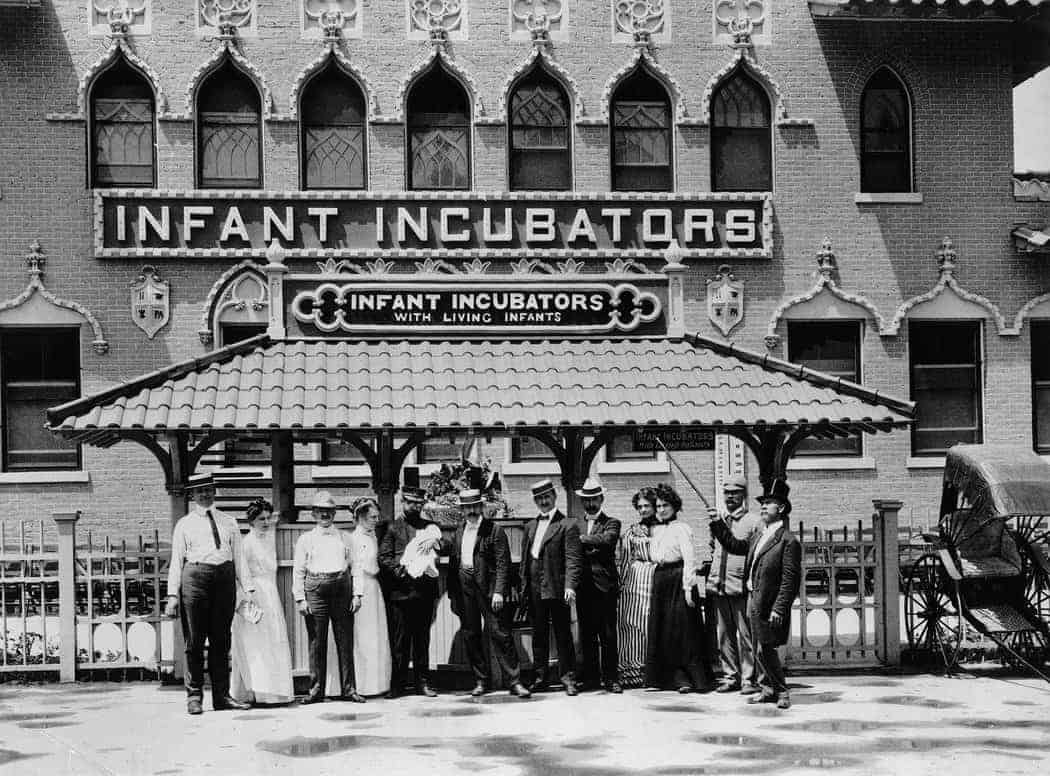

The Incubator Babies of Coney Island: How an Early 1900s Boardwalk Attraction Saved Thousands of Premature Babies Lives

Step right up, folks!

Thrill to the Fire and Flames show!

See the Bearded Lady!

Early in the 20th century, crowds flocked to New York City’s Coney Island, where wonders awaited at every turn.

In 1902, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle published a few of the highlights in store for visitors at Coney Island’s soon-to-open “electric Eden,” Luna Park:

…the most important will be an illustration of Jules Verne’s ‘Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea’, which will cover 55,000 square feet of ground, and a naval spectatorium, which will have a water area of 60,000 square feet. Beside these we will have many novelties, including the River Styx, the Whirl of the Town, Shooting the White Horse Rapids, the Grand Canyon, the ’49 Mining Camp, Dragon Rouge, overland and incline railways, Japanese, Philippine, Irish, Eskimo and German villages, the infant incubator, water show and carnival, circus and hippodrome, Yellowstone Park, zoological gardens, performing wild beasts, sea lions and seals, caves of Capri, the Florida Everglades and Mont Pelee, an electric representation of the volcanic destruction of St. Pierre.

Hold up a sec…what’s this about an infant incubator? What kind of name is that for a roller coaster!?

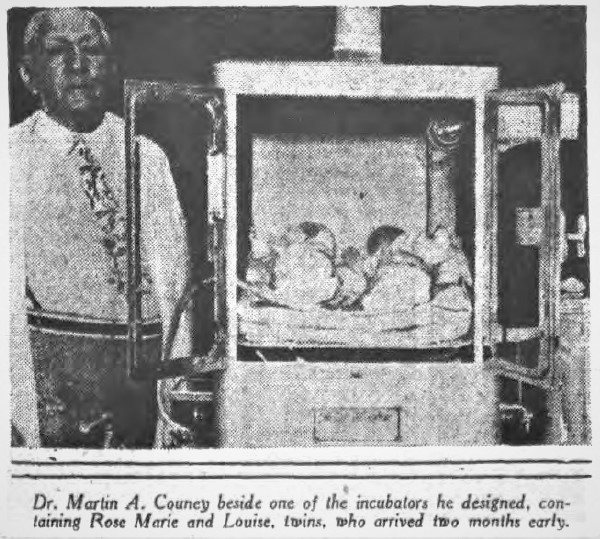

As it turns out, amid all the exotica and bedazzlements, a building furnished with steel and glass cribs, heated from below by temperature-controlled hot water pipes, was one of the boardwalk’s leading attractions.

Antiseptic-soaked wool acted as a rudimentary air filter, while an exhaust fan kept things properly ventilated.

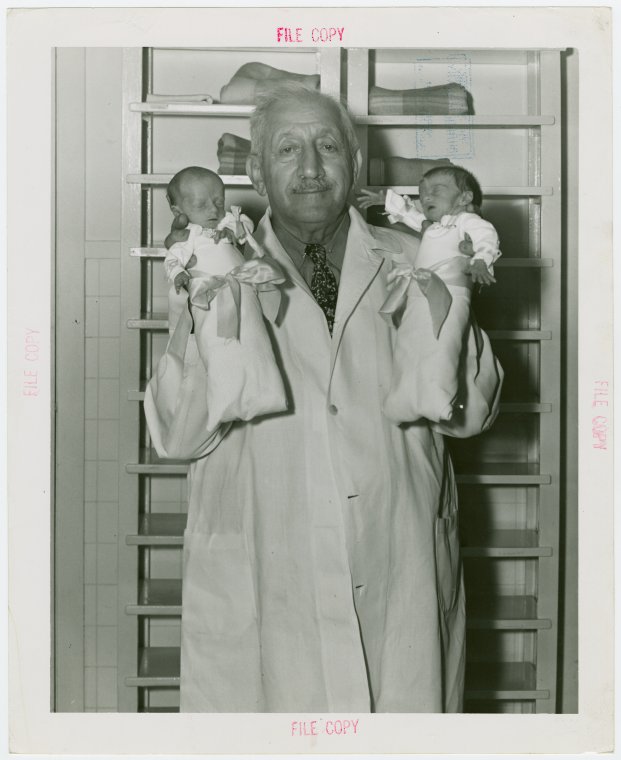

The real draw were the premature babies who inhabited these cribs every summer, tended to round the clock by a capable staff of white clad nurses, wet nurses and Dr. Martin Couney, the man who had the ideas to put these tiny newborns on display…and in so doing, saved thousands of lives.

Couney, a breast feeding advocate who once apprenticed under the founder of modern perinatal medicine, obstetrician Pierre-Constant Budin, had no license to practice.

Nor did he have an md.

Initially painted as a child-exploiting charlatan by many in the medical community, he was as vague about his background as he was passionate about his advocacy for preemies whose survival depended on robust intervention.

Having presented Budin’s Kinderbrutanstalt — child hatchery — to spectators at 1896’s Great Industrial Exposition of Berlin, and another infant incubator show as part of Queen Victoria Diamond Jubilee Celebration, he knew firsthand the public’s capacity to become invested in the preemies’ welfare, despite a general lack of interest on the part of the American medical establishment.

Thusly was the idea for the boardwalk Infantoriums hatched.

Claire Prentice, author of Miracle at Coney Island: How a Sideshow Doctor Saved Thousands of Babies and Transformed American Medicine, writes that “many doctors at the time held the view that premature babies were genetically inferior ‘weaklings’ whose fate was a matter for God.”

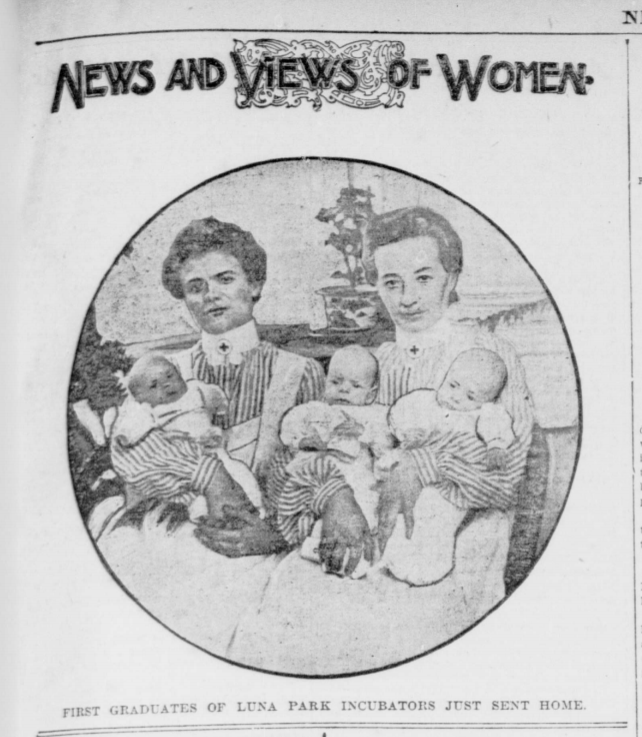

As word of Couney’s Infantorium spread, parents brought their premature newborns to Coney Island, knowing that their chances of finding a lifesaving incubator there was far greater than it would be in the hospital. And the care there would be both highly skilled and free, underwritten by paying spectators who observed the operation through a glass window. Prentice notes that “Couney took in babies from all backgrounds, regardless of race or social class:”

… a remarkably progressive policy, especially when he started out. He did not take a penny from the parents of the babies. In 1903 it cost around $15 (equivalent to around $405 today) a day to care for each baby; Couney covered all the costs through the entrance fees.

The New Yorker’s A. J. Liebling observed Couney at the 1939 World’s Fair in Flushing, Queens, where he had set up in a pink-and-blue building that beckoned visitors with a sign declaring “All the World Loves a Baby:”

The backbone of Dr. Couney’s business is supplied by the repeaters. A repeater becomes interested in one baby and returns at intervals of a week or less to note its growth. Repeaters attend more assiduously than most of the patients’ parents, even though the parents get in on passes. After a preemie graduates, a chronic repeater picks out another one and starts watching it. Dr. Couney’s prize repeater, a Coney Island woman named Cassatt, visited his exhibit there once a week for thirty-six seasons. Repeaters, as one might expect, are often childless married people, but just as often they are interested in babies because they have so many children of their own. “It works both ways,” says Dr. Couney, with quiet pleasure.

It’s estimated that Couney’s incubators spared the lives of more than 6,500 premature babies in the United States, London, Paris, Mexico and Brazil.

Despite his lack of bonafides, a number of pediatricians who toured Couney’s infantoriums were impressed by what they saw, and began referring patients whose families could not afford to pay for medical care. Many, as Liebling reported in 1939, wished his boardwalk attraction could stay open year round, “for the benefit of winter preemies:”

In the early years of the century no American hospital had good facilities for handling prematures, and there is no doubt that every winter many babies whom Dr. Couney could have saved died. Even today it is difficult to get adequate care for premature infants in a clinic. Few New York hospitals have set up special departments for their benefit, because they do not get enough premature babies to warrant it; there are not enough doctors and nurses experienced in this field to go around. Care of prematures as private patients is hideously expensive. One item it involves is six dollars a day for mother’s milk, and others are rental of an incubator and hospital room, oxygen, several visits a day by a physician, and fifteen dollars a day for three shifts of nurses. The New York hospitals are making plans now to centralize their work with prematures at Cornell Medical Center, and probably will have things organized within a year. When they do, Dr. Couney says, he will retire. He will feel he has “made enough propaganda for preemies.”

Listen to a StoryCorps interview with Lucille Horn, a 1920 graduate of Couney’s Coney Island incubators below.

Related Content

Why Babies in Medieval Paintings Look Like Middle-Aged Men: An Investigative Video

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. She greeted 2024 with thousands of other New Yorkers, taking a polar bear plunge at Coney Island. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...51 Propaganda Techniques Explained in 11 Minutes: From Cognitive Dissonance to Appeal to Fear

The concept of propaganda has a great deal of power to fascinate. So does the very word propaganda, which to most of us today sounds faintly exotic, as if it referred mainly to phenomena from distant places and times. But in truth, can any one of us here in the twenty-first century go a day without being subjected to the thing itself? Watch the video above, in which The Paint Explainer lays out 51 different propaganda techniques in 11 minutes, and you’ll more than likely recognize many of the insidiously effective rhetorical tricks labeled therein from your recent everyday life.

You won’t be surprised to hear that these manifest most clearly in the media, both offline and on. The list begins with “agenda setting,” the “ability of the news to influence the importance placed on certain topics by public opinion, just by covering them frequently and prominently.”

Scattered throughout the news, or throughout your social-media feed, advertisements bring out the “beautiful people,” which “suggests that if people buy a product or follow a certain ideology, they, too will be happy or successful” – or, in its basest forms, operates through “classical conditioning,” in which “a natural stimulus is associated with a neutral stimulus enough times to create the same response by using just the neutral one.”

In the even more shameless realm of politics, the common “plain folk” strategy “attempts to convince the audience that the propagandist’s positions reflect the common sense of the people.” When “an individual uses mass media to create an idealized and heroic public image, often through unquestioning flattery and praise,” a powerful “cult of personality” can arise. And in propaganda for everything from presidential candidates to fast-food chains, you’ll hear and read no end of “glittering generalities,” or “emotionally appealing words that are applied to a product idea, but present no concrete argument or analysis.” You can find many of these strategies explained at Wikipedia’s list of propaganda techniques, or this list from the University of Virginia of “propaganda techniques to recognize” — and not just when the “other side” uses them.

Related content:

Sell & Spin: The History of Advertising, Narrated by Dick Cavett (1999)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...How to Be Happier in 5 Research-Proven Steps, According to Popular Yale Professor Laurie Santos

Nature doesn’t care if you’re happy, but Yale psychology professor Laurie Santos does.

As Dr. Santos points out during the above appearance on The Well, the goals of natural selection have been achieved as long as humans survive and reproduce, but most of us crave something more to consider life worth living.

With depression rising to near epidemic levels on college campuses and elsewhere, it’s worth taking a look at our ingrained behavior, and maybe making some modifications to boost our happiness levels.

Psychology and the Good Life, Dr. Santos’ massive twice weekly lecture class that actively tackles ways of edging closer to happiness, is the most popular course in Yale’s more than 300-year history.

Do we detect some resistance?

Positive psychology — or the science of happiness — is a pretty crowded field lately, and the overwhelming demand created by great throngs of people longing to feel better has attracted a fair number of grifters willing to impart their proven methodologies to anyone enrolling in their paid online courses.

By contrast, Dr. Santos not only has that Yale pedigree, she also cites other respected academics such as the University of Chicago’s Nicholas Epley, a social cognition specialist who believes undersociality, or a lack of face-to-face engagement, is making people miserable, and Harvard’s Dan Gilbert and the University of Virginia’s Timothy Wilson, who co-authored a paper on “miswanting”, or the tendency to inaccurately predict what will truly result in satisfaction and happiness.

Yale undergrad Mickey Rose, who took Psychology and the Good Life in the spring of 2022 to fulfill a social science credit, told the Yale Daily News that her favorite part of the class was that “everything was cited, everything had a credible source and study to back it up:”

I’m a STEM major and it’s kind of my overall personality type to question claims that I find not very believable. Obviously the class made a lot of claims about money, grades, happiness, that are counterintuitive to most people and to Yale students especially.

With Psychology and the Good Life now available to the public for free on Coursera, even skeptics might consider giving Dr. Santos’ recommended “re-wirement practices” a peek, though be forewarned, you should be prepared to put them into practice before making pronouncements as to their efficacy.

It’s all pretty straightforward stuff, starting with “use your phone to actually be a phone”, meaning call a friend or family member to set up an in person get together rather than scrolling through endless social media feeds.

Other common sense adjustments include looking beyond yourself to help by volunteering, resolving to adopt a glass-is-half-full type attitude, cultivating mindfulness, making daily entries in a gratitude journal, and becoming less sedentary.

(You might also give Dr. Santos’ Happiness Lab podcast a go…)

Things to guard against are measuring your own happiness against the perceived happiness of others and “impact bias” — overestimating the duration and intensity of happiness that is the expected result of some hotly anticipated event, acquisition or change in social standing.

Below Dr. Santos gives a tour of the Good Life Center, an on-campus space that stressed out, socially anxious students can visit to get help putting some of those re-wirement practices into play.

Sign up for Coursera’s 10-week Science of Well-Being course here.

Related Content

The Science of Well-Being: Take a Free Online Version of Yale University’s Most Popular Course

Free Online Psychology & Neuroscience Courses, a subset of our collection, 1,700 Free Online Courses from Top Universities

What Are the Keys to Happiness? Lessons from a 75-Year-Long Harvard Study

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...A Lavishly Illustrated Catalog of All Hummingbird Species Known in the 19th Century Gets Restored & Put Online

If you don’t live in a part of the world with a lot of hummingbirds, it’s easy to regard them as not quite of this earth. With their wide array of shimmering colors and frenetic yet eerily stable manner of flight, they can seem like quasi-fantastical creatures even to those who encounter them in reality. They certainly captured the imagination of English ornithologist John Gould, who between the years of 1849 and 1887 created A Monograph of the Trochilidæ, or Family of Humming-Birds, a catalog of all known species of hummingbird at the time. As you might expect, this is just the kind of old book you can peruse at the Internet Archive, but now there’s also an online restoration that returns Gould’s illustrations to their original glory.

A Monograph of the Trochilidæ “is considered one of the finest examples of ornithological illustration ever produced, as well as a scientific masterpiece,” writes the site’s creator, Nicholas Rougeux (previously featured here on Open Culture for his digital restorations of British & Exotic Mineralogy and Euclid’s Elements).

“Gould’s passion for hummingbirds led him to travel to various parts of the world, such as North America, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru, to observe and collect specimens. He also received many specimens from other naturalists and collectors.” Taken together, the work’s five volumes — one of them published as a supplement years after his death — catalog 537 species, documenting their appearance with 418 hand-colored lithographic plates.

All these images were “analyzed and restored to their original vibrant colors in a process that took nearly 150 hours to complete. As much of the original plate was preserved — including the delicate colors of the scenic backgrounds in each vignette.” You can view and download them at the site’s illustrations page, where they come accompanied by Gould’s own text and classified according to the same scheme he originally used. You may not know your Phaëthornis from your Sphenoproctus, to say nothing of your Cyanomyia from your Smaragdochrysis, but after seeing these small wonders of the natural world as Gould did (all arranged into a chromatic spectrum by Rougeux to make a striking poster), you may well find yourself inspired to learn the differences — or at least to put a feeder outside your window.

via Kottke

Related content:

The Hummingbird Whisperer: Meet the UCLA Scientist Who Has Befriended 200 Hummingbirds

What Kind of Bird Is That?: A Free App From Cornell Will Give You the Answer

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...