Death-Cap Mushrooms are Terrifying and Unstoppable: A Wild Animation

Mushrooms are justly celebrated as virtuous multitaskers.

They’re food, teachers, movie stars, design inspiration…

…and some, as anyone who’s spent time playing or watching The Last of Us can readily attest, are killers.

Hopefully we’ve got some time before civilization is conquered by zombie cordyceps.

For now, the ones to watch out for are amanita phalloide, aka death cap mushrooms.

The powerful amatoxin they harbor is behind 90 percent of mushroom-related fatalities worldwide. It causes severe liver damage, leading to bleeding disorders, brain swelling, and multi-organ failure in those who survive.

A death cap took the life of a three-year-old in British Columbia who mistook one for a tasty straw mushroom on a foraging expedition with his family near their apartment complex.

In Melbourne, a pot pie that tested positive for death caps resulted in the deaths of three adults, and sent a fourth to the hospital in critical condition.

As the animators feast on mushrooms’ limitless visual appeal in the above episode of The Atlantic’s Life Up Close series, author Craig Childs delivers some sobering news:

We did it to ourselves. Humans are the ones who’ve enabled death caps to spread so far beyond their native habitats in Scandinavia and parts of northern Europe, where the poisonous fungi feed on the root tips of deciduous trees, springing up around their hosts in tidy fairy rings.

When other countries import these trees to beautify their city streets, the death caps, whose fragile spores are incapable of traveling long distances when left to their own devices, tag along.

They have sprouted in the Pacific Northwest near imported sweet chestnuts, beeches, hornbeams, lindens, red oaks, and English oaks, and other host species.

As biochemist Paul Kroeger, cofounder of the Vancouver Mycological Society, explained in a 2019 article Childs penned for the Atlantic, the invasive death caps aren’t popping up in deeply wooded areas.

Rather, they are settling into urban neighborhoods, frequently in the grass strips bordering sidewalks. When Childs accompanied Krueger on his rounds, the first of two dozen death caps discovered that day were found in front of a house festooned with Halloween decorations.

Now that they have established themselves, the death caps cannot be rousted. No longer mere tourists, they’ve been seen making the jump to native oaks in California and Western Canada.

Childs also notes that death caps are no longer a North American problem:

They have spread worldwide where foreign trees have been introduced into landscaping and forestry practices: North and South America, New Zealand, Australia, South and East Africa, and Madagascar. In Canberra, Australia, in 2012, an experienced Chinese-born chef and his assistant prepared a New Year’s Eve dinner that included, unbeknownst to them, locally gathered death caps. Both died within two days, waiting for liver transplants; a guest at the dinner also fell ill, but survived after a successful transplant.

Foragers should proceed with extreme caution.

Related Content

The Beautifully Illustrated Atlas of Mushrooms: Edible, Suspect and Poisonous (1827)

Algerian Cave Paintings Suggest Humans Did Magic Mushrooms 9,000 Years Ago

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...Fascism!: The US Army Publishes a Pamphlet in 1945 Explaining How to Spot Fascism at Home and Abroad

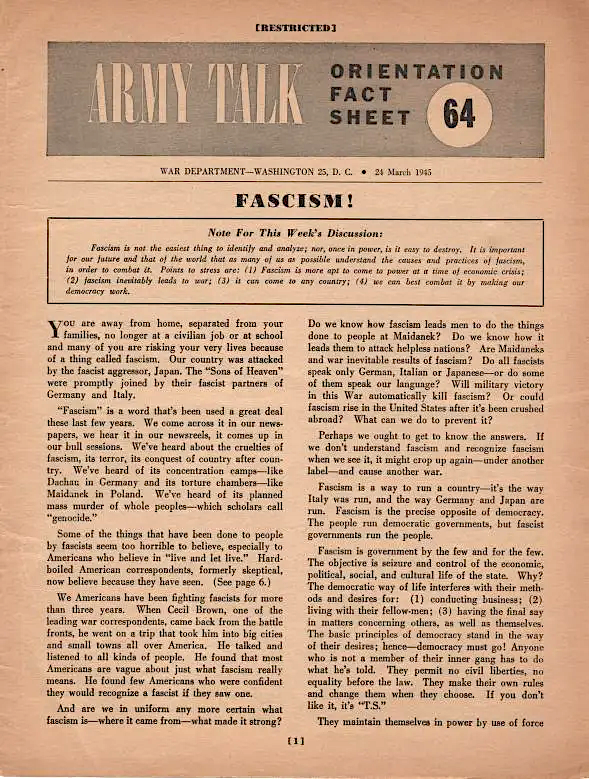

“Fascism is a word that’s been used a great deal these last few years,” says the article pictured above (scanned in full here at the Internet Archive). “We come across it in our newspapers, we hear it in our newsreels, it comes up in our bull sessions.” Other than the part about newsreels (today’s equivalent being our social-media feeds, or perhaps the videos put before our eyes by the algorithm), these sentences could well have been published today. Some see the fascist takeover of modern-day democracies as practically imminent, while others argue that the concept itself has no meaning in the twenty-first century. But 78 years ago, when this issue of Army Talk came off the press, fascism was very much a going — and fearsome — concern.

“Beginning in 1943, the War Department published a series of pamphlets for U.S. Army personnel in the European theater of World War II,” writes historian Heather Cox Richardson. The mission of Army Talks, in the publication’s own words, was to help its readers “become better-informed men and women and therefore better soldiers.”

Each issue included a topic for discussion, and on March 25, 1945, that topic was fascism — or, as the headline puts it, “FASCISM!” Under that ideology, defined as “government by the few and for the few,” a small group of political actors achieves “seizure and control of the economic, political, social, and cultural life of the state.” Such ruling classes “permit no civil liberties, no equality before the law. They make their own rules and change them when they choose. If you don’t like it, it’s ‘T.S.’ ”

Fascists come to power, the text explains, in times of hardship, during which they promise “everything to everyone”: land to the farmers, jobs to the workers, customers and profits to the small businessmen, elimination of small businessmen to the industrialists, and so on. When this regime “under which everything not prohibited is compulsory” inevitably fails to deliver a perfect society, things turn violent, both in the country’s internal struggles and in its conflicts with other powers. To many Americans at the time of World War II, this might seem like a wholly foreign disorder, liable to afflict only such distant lands as Italy, Japan, and Germany. But a notional American fascism would look and feel familiar, working “under the guise of ‘super-patriotism’ and ‘super-Americanism.’ Fascist leaders are neither stupid nor naïve. They know that they must hand out a line that ‘sells.’ ”

That someone’s always trying to sell you something in politics — and even more so in American politics — is as true in 2023 as it was in 1945. Though whoever assumed back then that “it couldn’t happen here” presumably figured that the United States was too wealthy a society for fascist temptations to gain a foothold. But even the most favorable economic fortunes can reverse, and “lots of things can happen inside of people when they are unemployed or hungry. They become frightened, angry, desperate, confused. Many, in their misery, seek to find somebody to blame. They look for a scapegoat as a way out. Fascism is always ready to provide one.” And not only fascism: political opportunists of every stripe know full well the power to be drawn from “the insecure and unemployed” looking for someone on who “to pin the blame for their misfortune” — and how easy it is to do so when no one else has a more appealing vision of the future to offer.

You can see a scan of the original document here, and read the text here.

Related content:

How to Spot a Communist Using Literary Criticism: A 1955 Manual from the U.S. Military

Umberto Eco Makes a List of the 14 Common Features of Fascism

Walter Benjamin Explains How Fascism Uses Mass Media to Turn Politics Into Spectacle (1935)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Watch Young David Attenborough Encounter Animals in Their Natural Habitats: Video from the 1950s and 1960s

Experience long ago conferred the mantle of authority on broadcaster, biologist, natural historian and author David Attenborough, age 97.

In his late 20s, he landed at the BBC, producing live studio broadcasts that ran the gamut from children’s shows, ballet performances and archeological quizzes to programs focused on cooking, religion and politics.

When an educational show starring animals from the London Zoo became a hit with viewers, the powers that be built on its popularity with a fresh take — a show that sent the intrepid young Attenborough around the world, seeking animals in their native habitats. He was accompanied by cameraman Charles Lagus and two zoologists, whom he quickly supplanted as host.

It made for thrilling viewing in an era when wildlife tourism was available to a very few.

The New York Times notes that many of the creatures who cropped up onscreen in these early Zoo Quest episodes were shipped back to London Zoo:

It is not the kind of mission we approve of nowadays, but without it the West might never have gotten interested in wildlife to begin with. We started by shooting exotic species for their skins and bones and trapping them for our zoos, and only recently moved to worrying about their survival in the wild and the health of the planet in general. This history is symbolized by the transformation of Attenborough himself from a talking and writing crocodile hunter to the greatest living advocate of the global ecosystem.

In Borneo in 1956, in search for Komodo dragons, he paused for an encounter with an orangutan, above, and also a big whiff of durian, the spiky, odiferous fruit whose aroma famously got it banned from Singapore’s elegant Raffles Hotel, with taxis, planes, subways, and ferries following suit.

Soon thereafter, the six-episode hunt for the Komodo dragon finds Attenborough in Java, masking his nerves as he uses a cutlass, a willingness to climb trees, and a cloth sack to get the better of a fully grown python.

(Once the serpent was settled at the London Zoo, he made the trek to the BBC for an in-studio appearance.)

You’ll note that this episode is in color.

Although Zoo Quest filmed in color, it aired ten years before color broadcasts were available to UK viewers, so most of the folks watching at home assumed it had been shot in black and white.

In 1960, Attenborough used the latest — now severely outmoded-looking– technology to capture the first audio recording of the indri, Madagascar’s largest lemur for Attenborough’s Wonder of Song.

This audio victory led him to wonder if he could be the first to film an indri.

Frustrated by the thick canopy overhead, Attenborough resorted to playback, successfully tempting the animals to not only come closer, but do so while vocalizing.

Mating calls?

No. Attenborough deduced that they were the indris’ “battle songs”, issued as a warning to the perceived threat of unfamiliar indris.

In 2011, Attenborough returned to Madagascar, listening respectfully to Joseph, a local hunter turned conservationist, who explains how the local populace no longer think of indri as a food source, but rather a symbol of their commitment to preserving the natural world around them. Joseph’s relationship with the indri affords Sir David a rare opportunity, as the indri feed from his hand:

Fifty years ago, I spent days and days and days searching through the forest, with these firing their noise overhead but now this group is so accustomed to seeing people around that I have been right close up to them, something I never believed could have be possible.

Read more about David Attenborough’s Zoo Quest experiences in his memoir, Adventures of a Young Naturalist, and watch a playlist of documentaries for the BBC here.

Related Content

David Attenborough Reads “What a Wonderful World” in a Moving Video

Björk and Sir David Attenborough Team Up in a New Documentary About Music and Technology

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...Gordon Ramsay’s Ultimate Cookery Course: Free Video Lessons

Our definition of budget cookery may differ from celebrity chef Gordon Ramsey’s.

True, the world famous restauranteur and cookbook author speaks of cheap cuts with messianic zeal, but the episode of Gordon Ramsey’s Ultimate Cookery Course dedicated to Food on a Budget, above, also finds him paying a call to Lina Stores’ SoHo location to discuss ham, sausages, and salami with the late “deli maestro” Antonio Saccomani.

It’s not exactly Costco.

Nor can we buy bone-in Lamb with fried bread as a cost conscious dish, though the accompanying milk soaked fried bread — homemade croutons really — will cost slightly less to make this year, as the USDA is predicting that dairy prices will fall after 2022’s historic levels.

As long as we’re at peace with the idea that the man is not ever going to be found stretching rice and beans to feed a family of four for a week when there’s leftover risotto to be resurrected as arancini, the series is a goldmine for chefs of all budgets and experience levels.

It’s not so much the final dishes, as the short cuts and best practices on the journey.

His “chef in Paris” might indeed kill him for uglying up a dish with deliciously humble pan scrapings, but his ironclad maxims to waste nothing and use available ingredients will benefit home chefs with an eye on the bottom line, as well as pros in high end restaurants where profit margins turn on a knife’s edge.

In an age when any fool can Google up dozens of foolproof methods for cooking rice, sometimes it’s reassuring to get this sort of intel straight from the lips of a globally recognized expert. (We’re big fans of Julia Child’s scrambled eggs…)

How does your method measure up against Ramsey’s freely shared secret for cooking perfect rice?

Weigh out 400 grams of rice on a kitchen scale

Rinse with cold water

Season with salt and pepper, and — going up the food chain a bit — 3 pierced cardamom pods and a star anise

Add 600 grams of water (that’s a 1:1.5 ratio for those playing along without kitchen scales or the metric system)

Bring to a boil, and steam, covered for 8–10 minutes

No peeking!

Remove pot from heat and fluff

Such universal tips are the most persuasive reason to stick with the series.

Ramsey’s rapid fire delivery and lack of linked recipes may leave you feeling a bit lost in regard to exact measurements, temperatures, and step by step instructions, but keep your ears peeled and you’ll quickly pick up on how to extend fresh herbs’ shelf life and keep cut potatoes, apples and avocados looking their best.

Other episodes reveal how to grease cake tins, prevent milk from boiling over, remove baked-on residue, peel kiwis and mangos, determine a pineapple’s ripeness, seed pomegranates, skin tomatoes, and keep plastic containers stain-free…

Seriously, who needs TikTok when we have Gordon Ramsey 2012?

Ramsey’s advice to bypass expensive wine when cooking those comparatively cheap cuts of meat low and slow gets a chef’s kiss from us. (In full disclosure, we would happily swig his braising vintage.)

As to the slow-cooked duck, truffles and caramelized figs with ricotta, we must remind ourselves that the series is over 10 years old. These days even eggs feel like a splurge..

Perhaps some stress free cooking tips will lower our stress level over this week’s grocery expenditures?

Here too, there seems to be some discrepancy in Ramsey’s definition and the general public’s. His idea of stress free is achieved through lots of prepwork

If your idea of de-stressing involves skinning & deboning a salmon or making homemade fish stock, you’re in luck.

Obviously the end product will be delicious but the phrase “chili chicken with ginger & coriander” activates both our salivary glands and our impulse to order out…

Watch a full playlist of Gordon Ramsay’s Ultimate Cookery Course here.

Related Content

Watch Anthony Bourdain’s First Food-and-Travel Series A Cook’s Tour Free Online (2002–03)

Watch 26 Free Episodes of Jacques Pépin’s TV Show, More Fast Food My Way

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...How to Silence the Negative Chatter in Our Heads: Psychology Professor Ethan Kross Explains

A couple of weeks ago, the New York Times published an article headlined “How to Stop Ruminating.” If your social media feeds are anything like mine, you’ve seen it pop up with some frequency since then. “Perhaps you spend hours replaying a tense conversation you had with your boss over and over in your head,” writes its author Hannah Seo. “Maybe you can’t stop thinking about where things went wrong with an ex during the weeks and months after a breakup.” The piece’s popularity speaks to the commonness of these tendencies.

But if “your thoughts are so excessive and overwhelming that you can’t seem to stop them,” leading to distraction and disorganization at work and at home, “you’re probably experiencing rumination.” For this broader phenomenon University of Michigan psychology professor Ethan Kross has a more evocative name: chatter.

“Your inner voice is your ability to silently use language to reflect on your life,” he explains in the Big Think video above. “Chatter refers to the dark side of the inner voice. When we turn our attention inward to make sense of our problems, we don’t end up finding solutions. We end up ruminating, worrying, catastrophizing.”

Despite being an invaluable tool for planning, memory, and self-control, our inner voice also has a way of turning against us. “It makes it incredibly hard for us to focus,” Kross says, and it can also have “severe negative physical health effects” when it keeps us perpetually stressing out over long-passed events. “We experience a stressor in our life. It then ends, but in our minds, our chatter perpetuates it. We keep thinking about that event over and over again.” When you’re inside them, such mental loops can feel infinite, and they could result in perpetually dire consequences in our personal and professional lives. To those in need of a way to break free, Kross emphasizes the power of rituals.

“When you experience chatter, you often feel like your thoughts are in control of you,” he says. But “we can compensate for this feeling out of control by creating order around us. Rituals are one way to do that.” Performing certain actions exactly the same way every single time gives you “a sense of order and control that can feel really good when you’re mired in chatter.” Kross goes into greater depth on the range of chatter-controlling tools available to us (“distanced-self talk,” for example, which involves perceiving and addressing the self as if it were someone) in his book Chatter: The Voice in Our Head, Why It Matters, and How to Harness It. His interview with Chase Jarvis above offers a preview of its content — and a reminder that, as means of silencing chatter go, sometimes a podcast works as well as anything.

Related content:

Why You Do Your Best Thinking In The Shower: Creativity & the “Incubation Period”

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...How to Watch Hundreds of Free Movies on YouTube

We lived in the age of movie theaters, then we lived in the age of home video, and now we live in the age of streaming. Like every period in the history of cinema, ours has its advantages and its disadvantages. The quasi-religiosity of the cinephile viewing experience is, arguably, not as well served by clicking on a Youtube video as it is by attending a screening at a grand revival house. But on the whole, we do have the advantage of access, whenever and wherever we like, to a great many films that most of us may have been wholly unable to see just a couple of decades ago — and often, we can watch them for free.

That said, these are still relatively early days for on-demand viewing, and finding out just where to do it isn’t as easy as it could be. That’s why we’ve rounded up this collection of Youtube channels with free movies, which together constitute one big meta-collection of hundreds of films. Among them are numerous black-and-white classics, of course, but also critically acclaimed pictures by international auteurs, rather less critically acclaimed (but nonetheless enjoyable) cult favorites, documentaries on a wide variety of subjects, and even twenty-first-century Hollywood releases.

Which films you can watch will vary, unfortunately, depending on which part of the world you happen to be watching them in. But no matter your location, you should easily be able to find more than a few worthwhile selections on all these channels. One under-appreciated aspect of our streaming age is that, though the number of choices may sometimes overwhelm, it’s never been easier to give a movie a chance. One click may, after all, transport you into a picture that changes the way you experience cinema itself — and if it doesn’t, well, at least the price was right.

- Cult Cinema Classics: This channel features cult classic films from the 30s, 40s, 50s, 60, 70s and 80s, providing access to 100 horror films, almost 400 western films, and a large number of Pre-Code films.

- Kino Lorber: Kino Lorber, a leading film distributor, has put 145 films on YouTube. The collection includes 80 documentaries on topics like on M.C. Escher, Stanley Kubrick, Hannah Arendt, and Hilma af Klint.

- Korean Classic Films: This channel lets you experience decades of Korean cinema, including but not limited to those of mid-20th-century masters like Kim Ki-young, Im Kwon-taek, and Kim Soo-yong, director of haunting, even brazen pictures of the 1960s and 70s like Mist and Night Journey. Enter the channel here.

- Mosfilm: One of the oldest film studios in Russia & Europe, Mosfilm has put online hundreds of Russian and Soviet films, many with English subtitles. The collection includes major films by Andrei Tarkovsky and an epic adaptation of War & Peace. Here, you will also find Battleship Potemkin and other films by Sergei Eisenstein. Enter the channel here.

- National Film Board of Canada: Canada’s public film producer and distributor has put online a large collection of short films. The channel features over 50 films from celebrated Canadian animator Norman McLaren, plus curated collections of films from the 1940s, 50s, 60s, 70s, 80s, and beyond.

- New Yorker’s Screening Room: On The New Yorker’s YouTube channel, you can find a Screening Room that hosts nearly 70 award-winning short films. This collection includes some wonderful claymations and animations. We previously featured the collection on our site in 2021.

- PizzaFlix: A passion project created by two film industry professionals with 50 years combined experience. They control a large, privately-held broadcast-quality film & TV library and have put online over 300 cowboy westerns, 80+ noir films, 200+ classic thriller and mystery films, and a number of films by Roger Corman.

- Popcorn Flix: A little like PizzaFlix (above), this archive has playlists of action movies, sci fi films, westerns, thrillers, comedies, dramas, and more.

- Timeless Classic Movies: Just as the title says, it’s a fine collection of timeless classic movies. Among other things, you can find 35 noir films and 60 classic thrillers here.

- YouTube’s Free Streaming Movies: YouTube itself hosts a large number of free streaming movies, mostly mainstream Hollywood productions. That said, you can also find some classics there, like the Coen Brothers’O Brother, Where Art Thou?, Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams, Yasujiro Ozu’s Tokyo Story, and Clint Eastwood’s The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly and also Fistful of Dollars. Enter the channel here.

If you know of other YouTube channels that legitimately host films online, please add them to the comments section below.

And, for more films, be sure to explore our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More

Related Content

Watch 3,000+ Films Free Online from the National Film Board of Canada

Watch 30+ Exceptional Short Films for Free in The New Yorker’s Online Screening Room

Watch More Than 400 Classic Korean Films Free Online Thanks to the Korean Film Archive

Charade, the Best Hitchcock Film Hitchcock Never Made: Stars Cary Grant & Audrey Hepburn

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Hear Moby Dick Read in Its Entirety by Tilda Swinton, Stephen Fry, John Waters & Many Others

“Moby-Dick is the great American novel. But it is also the great unread American novel. Sprawling, magnificent, deliriously digressive, it stands over and above all other works of fiction, since it is barely a work of fiction itself. Rather, it is an explosive exposition of one man’s investigation into the world of the whale, and the way humans have related to it. Yet it is so much more than that.”

That’s how Plymouth University introduces Herman Melville’s classic tale from 1851. And it’s what set the stage for their web project launched back in 2012. Called The Moby-Dick Big Read, the project featured celebrities and lesser known figures reading all 135 chapters from Moby-Dick — chapters that you can start downloading (as free audio files) on iTunes, Soundcloud, RSS Feed, or the Big Read web site itself.

The project started with the first chapters being read by Tilda Swinton (Chapter 1), Captain R.N. Hone (Chapter 2), Nigel Williams (Chapter 3), Caleb Crain (Chapter 4), Musa Okwonga (Chapter 5), and Mary Norris (Chapter 6). John Waters, Stephen Fry, Simon Callow, Mary Oliver and even Prime Minister David Cameron read later ones.

If you want to read the novel as you go along, find the text over at Project Gutenberg.

Tilda Swinton’s narration of Chapter 1 appears right below:

An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2012.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

An Illustration of Every Page of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick

How Ray Bradbury Wrote the Script for John Huston’s Moby Dick (1956)

Read More...An AI-Generated Painting Won First Prize at a State Fair & Sparked a Debate About the Essence of Art

Théâtre D’opéra Spatial by Jason Allen Jason Allen via Discord

The technology behind artificial intelligence-aided art has long been in development, but the era of artificial intelligence-aided art feels like a sudden arrival. Since the recent release of DALL‑E and other image-generation tools, our social-media feeds have filled up with elaborate artworks and even photorealistic-looking pictures created entirely through the algorithmic processing of a simple verbal description. We now live in a time, that is to say, where we type in a few words and get back an image nobody has ever before imagined, let alone seen. And if we do it right, that image could win a blue ribbon at the state fair.

“This year, the Colorado State Fair’s annual art competition gave out prizes in all the usual categories: painting, quilting, sculpture,” reports the New York Times’ Kevin Roose. “But one entrant, Jason M. Allen of Pueblo West, Colo., didn’t make his entry with a brush or a lump of clay. He created it with Midjourney, an artificial intelligence program that turns lines of text into hyper-realistic graphics.” The work, Théâtre D’opéra Spatial, “took home the blue ribbon in the fair’s contest for emerging digital artists,” and it does look, at first glance, like an impressionistic and ambience-rich past-future vision that could grace the cover of one of the better class of science-fiction or fantasy novels.

Reactions have, of course, varied. Roose finds at least one Twitter user insisting that “we’re watching the death of artistry unfold right before our eyes,” and an actual working artist claiming that “this thing wants our jobs.” Allen himself provides a helpfully brash closing quote: “This isn’t going to stop. Art is dead, dude. It’s over. A.I. won. Humans lost.” Over on Metafilter, one commenter makes the expected reference: “It has a sort of Duchamp-submitting-Fountain vibe, only in reverse. Instead of the proposition being that the jury would wrongly fail to recognize something trivial and as art, now we have the proposition that the jury would wrongly fail to recognize that the art is something trivial.”

However little desire you may have to hang Théâtre D’opéra Spatial on your own wall, a moment’s thought will surely lead you to suspect that, on another level, the conditions that brought about its victory are anything but trivial. Midjourney, as the original poster on Metafilter explains, “can be run on any computer with a decent GPU, a Google collab, or run through their own servers.” The ability to generate more-or-less convincing works of art (often littered, it must be said, with the bizarre visual glitches that have been the technology’s signature so far) out of just a few keystrokes will only become more powerful and more widespread. And so the “real” artists must find a new form too vital for the machines to master — just as they’ve had to do all throughout modernity.

Related content:

Discover DALL‑E, the Artificial Intelligence Artist That Lets You Create Surreal Artwork

The Long-Lost Pieces of Rembrandt’s Night Watch Get Reconstructed with Artificial Intelligence

AI & X‑Rays Recover Lost Artworks Underneath Paintings by Picasso & Modigliani

Artificial Intelligence Brings Salvador Dalí Back to Life: “Greetings, I Am Back”

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Read More...Dolly Parton’s Imagination Library Has Given Away 186 Million Free Books to Kids, Boosting Literacy Worldwide

Dolly Parton created her Imagination Library, a non-profit which gives books to millions of children every month, with her father, Robert Lee Parton, in mind.

“I always thought that if Daddy had an education, there’s no telling what he could have been,” she mused in her 2020 book, Songteller: My Life in Lyrics:

Because he knew how to barter, he knew how to bargain. He knew how to make everything work, and he knew how to count money. He knew exactly what everything was worth, how much he was going to make from that tobacco crop, what he could trade, and how he could make it all work

Despite his business acumen, Parton’s father never learned to read or write, a source of shame.

Parton explains how there was a time when schooling was never considered a given for children in the mountains of East Tennessee, particularly for those like her father, who came from a family of 15:

Kids had to go to work in the fields to help feed the family. Because of the weather and because of conditions, a lot of kids couldn’t go to school.

I told him, “Daddy, there are probably millions of people in this world who don’t know how to read and write, who didn’t get the opportunity. Don’t be ashamed of that. Let’s do something special.”

Parton is convinced that her father, whose pride in her musical accomplishments was so great he drove over with a bucket of soapy water to clean the bronze statue her hometown erected in her honor, was prouder still of a nickname bestowed on her by the Imagination Library’s child beneficiaries — the Book Lady.

Together with the community partners who secure funding for postage and non-administrative costs, the Book Lady has given away some 186,680,000 books since the project launched in 1995.

Originally limited to children residing in Sevier County, Tennessee, the program has expanded to serve over 2,000,000 kids in the US, UK, Australia, Canada and the Republic of Ireland.

Participation can start well before a child is old enough to attempt their ABCs. Parents and guardians are encouraged to enroll them at birth.

The Imagination Library’s littlest participants’ love of books is fostered with colorful illustrations and simple texts, often rhymes having to do with animals or bedtime.

By the time a reader hits their final year of the program at age 5, the focus will have shifted to school readiness, with subjects including science, folktales, and poetry.

The books — all Penguin Random House titles — are chosen by a panel of early childhood literacy experts.

This year’s selection includes such old favorites as The Tale of Peter Rabbit, Good Night, Gorilla, and The Snowy Day, as well as Parton’s own Coat of Many Colors, based on the song in which she famously paid tribute to her mother’s tender resourcefulness:

Back through the years

I go wonderin’ once again

Back to the seasons of my youth

I recall a box of rags that someone gave us

And how my momma put the rags to use

There were rags of many colors

Every piece was small

And I didn’t have a coat

And it was way down in the fall

Momma sewed the rags together

Sewin’ every piece with love

She made my coat of many colors

That I was so proud of

The Imagination Library is clearly a boon to children living, as Parton once did, in poverty, but participation is open to anyone under age 5 living in an area served by an Imagination Library affiliate.

Promoting early engagement with books in such a significant way has also helped Parton to reduce some of the stigma surrounding illiteracy:

You don’t really realize how many people can’t read and write. Me telling the story about my daddy instilled some pride in people who felt like they had to keep it hidden like a secret. I get so many letters from people saying, “I would never had admitted it’ or “I was always ashamed.”

Learn more about Dolly Parton’s Imagination Library, which welcomes donations and inquiries from those who would like to start an affiliate program in their area, here.

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...When Helen Keller Met Charlie Chaplin and Taught Him Sign Language (1919)

Charlie Chaplin had many high-profile fans in his day, including some of the luminaries of the early twentieth century. We could perhaps be forgiven for assuming that the writer and activist Hellen Keller was not among them, given the limitations her condition of deafness and blindness — or “deafblindness” — would naturally place on the enjoyment of film, even the silent films in which Chaplin made his name. But making that assumption would be to misunderstand the driving force of Keller’s life and career. If the movies were supposedly unavailable to her, then she’d make a point of not just watching them, but befriending their biggest star.

Keller met Chaplin in 1919 at his Hollywood studio, during the filming of Sunnyside. This, as biographers have revealed, was not one of the smoothest-going periods in the comedian-auteur’s life, but that didn’t stop him from enjoying his time with Keller, and even learning from her.

In her 1928 autobiography Midstream, she would remember that he’d been “shy, almost timid,” and that “his lovely modesty lent a touch of romance to the occasion that might otherwise have seemed quite ordinary.” The pictures that have circulated of the meeting, seen here, include one of Keller teaching Chaplin the tactile sign-language alphabet she used to communicate.

It was also the means by which, with the assistance of companion Anne Sullivan, she followed the action of Chaplin’s films A Dog’s Life and Shoulder Arms when they were screened for her that evening. When Keller and Chaplin met again nearly thirty years later, he sought her feedback on the script for his latest picture, Monsieur Verdoux. “There is no language for the terrifying power of your message that sears with sarcasm or rends apart coverts of social hypocrisy,” Keller later wrote to Chaplin. A politically charged black comedy about a bigamist serial killer bearing little resemblance indeed to the beloved Little Tramp, Monsieur Verdoux met with critical and commercial failure upon its release. The film has since been re-evaluated as a subversive masterwork, but it was perhaps Keller who first truly saw it.

Related content:

When Albert Einstein & Charlie Chaplin Met and Became Fast Famous Friends (1930)

When Mahatma Gandhi Met Charlie Chaplin (1931)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Read More...