The First Photographs Taken by the Webb Telescope: See Faraway Galaxies & Nebulae in Unprecedented Detail

Late last year we featured the amazing engineering of the James Webb Space Telescope, which is now the largest optical telescope in space. Capable of registering phenomena older, more distant, and further off the visible spectrum than any previous device, it will no doubt show us a great many things we’ve never seen before. In fact, it’s already begun: earlier this week, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center released the first photographs taken through the Webb telescope, which “represent the first wave of full-color scientific images and spectra the observatory has gathered, and the official beginning of Webb’s general science operations.”

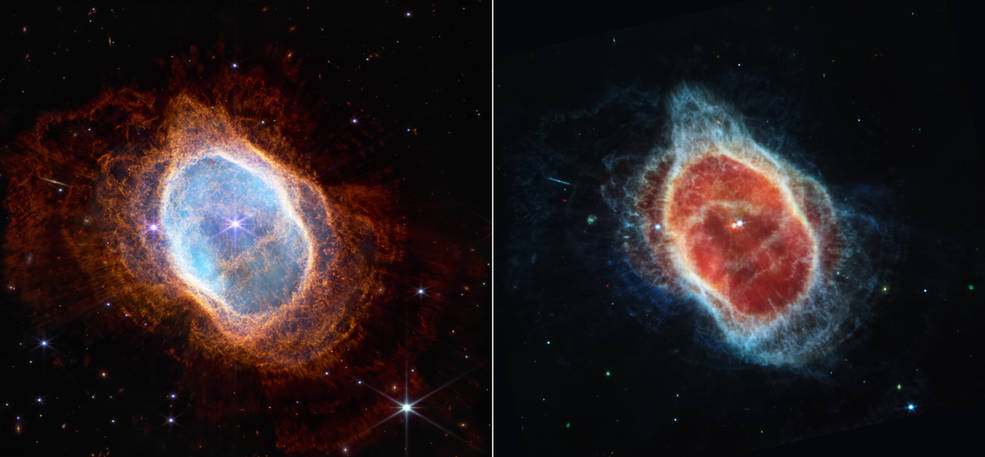

The areas of outer space depicted in unprecedented detail by these photos include the Carina Nebula (top), the Southern Ring Nebula (2nd image on this page), and the galaxy clusters known as Stephan’s Quintet (the home of the angels in It’s a Wonderful Life) and SMACS 0723 (bottom).

That last, notes Petapixel’s Jaron Schneider, “is the highest resolution photo of deep space that has ever been taken,” and the light it captures “has traveled for more than 13 billion years.” What this composite image shows us, as NASA explains, is SMACS 0723 “as it appeared 4.6 billion years ago” — and its “slice of the vast universe covers a patch of sky approximately the size of a grain of sand held at arm’s length by someone on the ground.”

All this can be a bit difficult to get one’s head around, at least if one is professionally involved with neither astronomy nor cosmology. But few imaginations could go un-captured by the richness of the images themselves. Sharp, rich in color, varied in texture — and in the case of the Carina Nebula or “Cosmic Cliffs,” NASA adds, “seemingly three-dimensional” — they could have come straight from a state-of-the-art science-fiction movie. In fact they outdo even the most advanced sci-fi visions, as NASA’s Earthrise outdid even the uncannily realistic-in-retrospect views of the Earth from space imagined by Stanley Kubrick and his collaborators in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

But these photos are the fruits of a real-life journey toward the final frontier, one you can follow in real time on NASA’s “Where Is Webb?” tracker. “Webb was designed to spend the next decade in space,” writes Colossal’s Grace Ebert. “However, a successful launch preserved substantial fuel, and NASA now anticipates a trove of insights about the universe for the next twenty years.” That’s quite a long run by the current standards of space exploration — but then, by the scale of space and time the Webb telescope has newly opened up, even 100 millennia is the blink of an eye.

Related content:

The Amazing Engineering of James Webb Telescope

How Scientists Colorize Those Beautiful Space Photos Taken By the Hubble Space Telescope

The Very First Picture of the Far Side of the Moon, Taken 60 Years Ago

The First Images and Video Footage from Outer Space, 1946–1959

The Beauty of Space Photography

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Read More...Julia Child Shows Fred Rogers How to Make a Quick & Delicious Pasta Dish (1974)

Julia Child and Fred Rogers were titans of public television, celebrated for their natural warmth, the ease with which they delivered important lessons to home viewers, and, for a certain sector of the viewing public, how readily their personalities lent themself to parody.

Child’s cooking program, The French Chef, debuted in 1963, and Roger’s much beloved children’s show, Mister Rogers Neighborhood, followed five years later.

Rogers occasionally invited accomplished celebrities to join him for segments wherein they demonstrated their particular talents:

With our guest’s help, I have been able to show a wide diversity of self-expression, the extraordinary range of human potential. I want children and their families to know that there are many constructive ways to express who they are and how they feel.

In 1974, Child paid a call to the neighborhood bakery presided over by “Chef” Don Brockett (whose later credits included a cameo as a “Friendly Psychopath” in Silence of the Lambs…)

The easy-to-prepare pasta dish she teaches Rogers — and, by extension, his “television friend” — to make takes a surprisingly optimistic view of the average pre-school palate.

Red sauce gets a hard pass, in favor of a more sophisticated blend of flavors stemming from tuna, black olives, and pimentos.

Brockett provides an assist with both the cooking and, more importantly, the child safety rules that aren’t always front and center with this celebrity guest.

Child, who had no offspring, comes off as a high-spirited, loosey-goosey, fun aunt, encouraging child viewers to toss the cooked spaghetti “fairly high” after adding butter and oil “because it’s dramatic” and talking as if they’ll be hitting the supermarket solo, a flattering notion to any tot whose refrain is “I do it mySELF!”

She wisely reframes tasks assigned to bigger, more experienced hand — boiling water, knife work — as less exciting than “the fancy business at the end”, and makes it stick by suggesting that the kids “order the grown ups to do what you want done,” a verb choice the ever-respectful Rogers likely would have avoided.

As with The French Chef, her off-the-cuff remarks are a major source of delight.

Watching his guest wipe a wooden cutting board with olive oil, Rogers observes that some of his friends “could do this very well,” to which she replies:

It’s also good for your hands ‘coz it keeps ‘em nice and soft, so rub any excess into your hands.

She shares a bit of stage set scuttlebutt regarding a letter from “some woman” who complained that the off-camera wastebasket made it appear that Child was discarding peels and stems onto the floor.

She said, “Do you think this is a nice way to show young people how to cook, to throw things on the floor!?” And I said, “Well, I have a self cleaning floor! …The self cleaning is me.”

(Rogers appears both amused and relieved when the ultimate punchline steers things back to the realm of good manners and personal responsibility.)

Transferring the slippery pre-cooked noodles from pot to serving bowl, Child reminisces about a wonderful old movie in which someone — “Charlie Chaplin or was it, I guess it was, uh, it wasn’t Mickey Rooney, maybe it was…” — eats spaghetti through a funnel.

If only the Internet had existed in 1974 so intrigued parents could have Googled their way to the Noodle Break at the Bull Pup Cafe sequence from 1918’s The Cook, starring Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle and Buster Keaton!

The funnel is but one of many inspired silent spaghetti gags in this surefire don’t‑try-this-at-home kid-pleaser.

We learn that Child named her dish Spaghetti Marco Polo in a nod to a widely circulated theory that pasta originated in China and was introduced to Italy by the explorer, a bit of lore food writer Tori Avey of The History Kitchen finds difficult to swallow:

A common belief about pasta is that it was brought to Italy from China by Marco Polo during the 13th century. In his book, The Travels of Marco Polo, there is a passage that briefly mentions his introduction to a plant that produced flour (possibly a breadfruit tree). The Chinese used this plant to create a meal similar to barley flour. The barley-like meal Polo mentioned was used to make several pasta-like dishes, including one described as lagana (lasagna). Since Polo’s original text no longer exists, the book relies heavily on retellings by various authors and experts. This, combined with the fact that pasta was already gaining popularity in other areas of Italy during the 13th-century, makes it very unlikely that Marco Polo was the first to introduce pasta to Italy.

Ah well.

We’re glad Child went with the China theory as it provides an excuse to eat spaghetti with chopsticks.

Nothing is more day-making than seeing Julia Child pop a small bundle of spaghetti directly into Fred Rogers’ mouth from the tips of her chopsticks…though after using the same implements to feed some to Chef Brockett too, she realizes that this wasn’t the best lesson in food hygiene.

In 2021, this sort of boo-boo would result in an automatic reshoot.

In the wilder, woolier 70s, a more pressing concern, at least as far as public television was concerned, was expanding little Americans’ worldview, in part by showing them how to get a commanding grip on their chopsticks. It’s never too late to learn.

Bon appétit!

JULIA CHILD’S SPAGHETTI MARCO POLO

There are a number of variations online, but this recipe, from Food.com, hews closely to Child’s original, while providing measurements for her eyeballed amounts.

Serves 4–6

INGREDIENTS

1 lb spaghetti

2 tablespoons butter

2 tablespoons olive oil

1 teaspoon salt black pepper

1 6‑ounce can tuna packed in oil, flaked, undrained

2 tablespoons pimiento, diced or 2 tablespoons roasted red peppers, sliced into strips

2 tablespoons green onions with tops, sliced

2 tablespoons black olives, sliced

2 tablespoons walnuts, chopped

1 cup Swiss cheese, shredded

2 tablespoons fresh parsley or 2 tablespoons cilantro, chopped

Cook pasta according to package directions.

Drain pasta and return to pot, stirring in butter, olive oil, and salt and pepper.

Toss with remaining ingredients and serve, garnished with parsley or cilantro.

Related Content

Julia Child Shows David Letterman How to Cook Meat with a Blow Torch

Watch Anthony Bourdain’s First Food-and-Travel Series A Cook’s Tour Free Online (2002–03)

Science & Cooking: Harvard’s Free Course on Making Cakes, Paella & Other Delicious Food

MIT Teaches You How to Speak Italian & Cook Italian Food All at Once (Free Online Course)

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...Two Decades of Fire Island DJ Sets Get Unearthed, Digitized & Put Online: Stream 232 Mixtapes Online (1979–1999)

“I was the young, lonely gay boy in the Midwest who had no idea paradise existed. Everything about the Pines was new, the very idea of a place where you could play on the beach and hold hands with a guy and be with like-minded people and dance all night with a man.” — photographer Tom Bianchi

Disco did not get demolished at Comiskey Park in 1979. It may have disappeared from popular culture after jumping the duck, but it never left the New York nightclubs that had nurtured its exuberant sound — Studio 54, Paradise Garage, The Sanctuary.… Four on the floor beats pounded all night in the dawning decade of the 80s, only the beat soon became house music, an electrified disco derivative — without the horns and string sections — first played in clubs by DJs like Larry Levan, who ruled the Paradise Garage for a decade and “changed dance music forever.”

The sounds of Manhattan nightlife at the turn of the 80s have gone mainstream, but stories about the early, underground days of house tend to leave out another scene just miles away, led by DJs as beloved as Levan.

For LGBTQ New Yorkers, the party moved every summer to Fire Island, where artists, vacationers, celebrities, and DJs crowded clubs like The Pavilion and the Ice Palace to hear DJs Robbie Leslie, Michael Jorba, Richie Bernier, Giancarlo, Teri Beaudoin, Michael Fierman, and Roy Thode, “whose performance at the Ice Palace showed how shimmery, guitar-driven disco slowly gave way to the driving bass of house music,” The New York Times notes.

Thode became a legend not only in the Fire Island summer scene but during his residency at Studio 54, at the personal invitation of club owner Steve Rubell. Fire Island DJs played records they heard in the off season at the island’s clubs, or debuted newly-released tracks. (Donna Summer’s “MacArthur Park” made its debut on the island, for example.) “Fire Island’s infamous bacchanals have gone on to become the stuff of gay myth and legend,” write Matt Moen at Paper. The island has also long been “an iconic refuge and safe haven for New York City’s queer community dating back well over half a century.” One resident calls it a “gay Shangri La.” Another compares it to Israel, a “spiritual homeland.”

Split between two towns, Cherry Grove and the Pines, the summer retreat has especially “been a haven for the creative,” says Bobby Bonnano, founder and president of the Fire Island Pines Historical Preservation Society. It has also been a hideaway for celebrities like Marilyn Monroe, Calvin Klein, and Perry Ellis. Bonnano’s extensive online history of the island documents its 20th century origins as a place for gay artists who built houses in a distinctive architectural style that defines the island to this day, and who partied hard at clubs like The Pavillion. The mixes here from Fire Island’s best DJs come from one such beach house, bought by Peter Kriss and Nate Pinsley, who discovered a box of tapes left behind by a previous owner.

The couple gave the box of tapes to their friend Joe D’Espinosa. A software engineer and DJ, D’Espinoza has spent “countless hours” digitizing, remastering, and uploading the collection to Mixcloud. The resulting archive represents a “treasure trove of recorded DJ sets,” spanning “two decades worth of parties,” Moen writes, from 1979 through 1999. The Pine Walk collection features more than 200 tapes (some from gigs in Manhattan),“taken from from Memorial Day weekenders, Labor Day parties, season openings and recurring club nights.” These are solid sets of vintage disco and classic house, many of them documenting the transition from one to the other. Browse and stream the full collection on Mixcloud.

Related Content:

Disco Saves Lives: Give CPR to the The Beat of Bee Gees “Stayin’ Alive”

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...The Rembrandt Book Bracelet: Behold a Functional Bracelet Featuring 1400 Rembrandt Drawings

Admittedly jewelry is not one of our areas of expertise, but when we hear that a bracelet costs €10,000, we kind of expect it to have a smattering of diamonds.

Designers Lyske Gais and Lia Duinker are getting that amount for a wristlet comprised chiefly of five large paper sheets printed with high res images downloaded free from the Rijksmuseum’s extensive digital archive of Rembrandt drawings and etchings.

Your average pawnbroker would probably consider its 18-karat gold clasp, or possibly the custom-made wooden box in which it can be stored when not in use the most precious thing about this ornament.

An ardent bibliophile or art lover is perhaps better equipped to see the book bracelet’s value.

Each gilt edged page — 1400 in all — features an image of a hand, sourced from 303 downloaded Rembrandt works.

An illustration on the designers’ Duinker and Dochters website details the painstaking process whereby the bookbracelet takes shape in 8‑page sections, or signatures, cross stitched tightly alongside each other on a paper band. Put it on, and you can flip through Rembrandt hands, Rolodex-style. When you want to do the dishes or take a shower, just pack it flat into that custom box.

Gais and Duinker also include an index, which is handy for those times when you don’t feel like hunting and pecking around your own wrist in search of a hand that appeared in the Flute Player or Christ crucified between the two murderers.

The Rembrandt’s Hands and a Lion’s Paw bracelet, titled like a book and published in a limited edition of 10, nabbed first prize in the 2015 Rijksstudio Awards, a competition that challenges designers to create work inspired by the Rijksmuseum’s collection.

(2015’s second prize went to an assortment of conserves and condiments that harkened to Johannes Hannot’s 1668 Still Life with Fruit. 2014’s winner was a palette of eyeshadow and some eyeliners inspired by Jan Adam Kruseman’s 1833 Portrait of Alida Christina Assink and a Leendert van der Cooghen sketch.)

But what about that special art loving bibliophile who already has everything, including a Rembrandts Hands and a Lions Paw boekarmband?

Maybe you could get them Collier van hondjes, Gais and Duinker’s follow up to the book bracelet, a rubber choker with an attached 112-page book pendant showcasing Rembrandt dogs sourced from various museum’s digital collections.

Purchase Rembrandt’s Hands and a Lions Paw limited edition book bracelet here.

And embark on making your own improbable thing inspired by a high res image in the Rijksmuseum’s Rijks Studio here.

via Colossal/Neatorama

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and creator, most recently of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...Aldous Huxley Predicts in 1950 What the World Will Look Like in the Year 2000

I’ve been thinking lately about how and why utopian fiction shades into dystopian. Though we sometimes imagine the two modes as inversions of each other, perhaps they lie instead on a continuum, one along which all societies slide, from functional to dysfunctional. The central problem seems to be this: Utopian thought relies on putting the complications of human behavior on the shelf to make a maximally efficient social order—or of finding some convenient way to dispense with those complications. But it is precisely with this latter move that the trouble begins. How to make the mass of people compliant and pacific? Mass media and consumerism? Forced collectivization? Drugs?

Readers of dystopian fiction will recognize these as some of the design flaws in Aldous Huxley’s utopian/dystopian society of Brave New World, a novel that asks us to wrestle with the philosophical problem of whether we can create a fully functional society without robbing people of their agency and independence. Doesn’t every utopia, after all, imagine a world of strict hierarchies and controls? The original—Thomas More’s Utopia—gave us a patriarchal slave society (as did Plato’s Republic). Huxley’s Brave New World similarly situates humanity in a caste system, subordinated to technology and subdued with medication.

While Huxley’s utopia has eradicated the nuclear family and natural human reproduction—thus solving a population crisis—it is still a society ruled by the ideas of founding fathers: Henry Ford, H.G. Wells, Freud, Pavlov, Shakespeare, Thomas Robert Malthus. If you wanted to know, in the early 20th century, what the future would be like, you’d typically ask a famous man of ideas. Redbook magazine did just that in 1950, writes Matt Novak at Paleofuture; they “asked four experts—curiously all men, given that Redbook was and is a magazine aimed at women—about what the world may look like fifty years hence.”

One of those men was Huxley, and in his answers, he draws on at least two of Brave New World’s intellectual founders, Ford and Malthus, in predictions about population growth and the nature of work. In addition to the ever-present threats of war, Huxley first turns to the Malthusian problems of overpopulation and scarce resources.

During the next fifty years mankind will face three great problems: the problem of avoiding war; the problem of feeding and clothing a population of two and a quarter billions which, by 2000 A.D., will have grown to upward of three billions, and the problem of supplying these billions without ruining the planet’s irreplaceable resources.

As Novak points out, Huxley’s estimation is “less than half of the 6.1 billion that would prove to be a reality by 2000.” In order to address the problem of feeding, housing, and clothing all of those people, Huxley must make an “unhappily… large assumption—that the nations can agree to live in peace. In this event mankind will be free to devote all its energy and skill to the solution of its other major problems.”

“Huxley’s predictions for food production in the year 2000,” writes Novak, “are largely a call for the conservation of resources. He correctly points out that meat production can be far less efficient than using agricultural lands for crops.” Huxley recommends sustainable farming methods and the development of “new types of synthetic building materials and new sources for paper” in order to curb the destruction of the world’s forests. What he doesn’t account for is the degree to which the overwhelming greed of a powerful few would drive the exploitation of finite resources and hold back efforts at sustainable design, agriculture, and energy—a situation that some might consider an act of war.

But Huxley’s utopian predictions depend upon putting aside these complications. Like many mid-century futurists, he imagined a world of increased leisure and greater human fulfillment, but he “sees that potential for better working conditions and increased standards of living as obtainable only through a sustained peace.” When it comes to work, Huxley’s forecasts are partly Fordist: Advances in technology are one thing, but “work is work,” he writes, “and what matters to the worker is neither the product nor the technical process, but the pay, the hours, the attitude of the boss, the physical environment.”

To most office and factory workers in 2000 the application of nuclear fission to industry will mean very little. What they will care about is what their fathers and mothers care about today—improvement in the conditions of labor. Given peace, it should be possible, within the next fifty years, to improve working conditions very considerably. Better equipped, workers will produce more and therefore earn more.

Unfortunately, Novak points out, “perhaps Huxley’s most inaccurate prediction is his assumption that an increase in productivity will mean an increase in wages for the average worker.” Despite rising profits and efficiency, this has proven untrue. In a Freudian turn, Huxley also predicts the decentralization of industry into “small country communities, where life is cheaper, pleasanter and more genuinely human than in those breeding-grounds of mass neurosis…. Decentralization may help to check that march toward the asylum, which is a threat to our civilization hardly less grave than that of erosion and A‑bomb.”

While technological improvements in materials may not fundamentally change the concerns of workers, improvements in robotics and computerization may abolish many of their jobs, leaving increasing numbers of people without any means of subsistence. So we’re told again and again. But this was not yet the pressing concern in 2000 that it is for futurists just a few years later. Perhaps one of Huxley’s most prescient statements takes head-on the issue facing our current society—an aging population in which “there will be more elderly people in the world than at any previous time. In many countries the citizens of sixty-five and over will outnumber the boys and girls of fifteen and under.”

Pensions and a pointless leisure offer no solution to the problems of an aging population. In 2000 the younger readers of this article, who will then be in their seventies, will probably be inhabiting a world in which the old are provided with opportunities for using their experience and remaining strength in ways satisfactory to themselves, and valuable to the community.

Given the decrease in wages, rising inequality, and loss of home values and retirement plans, more and more of the people Huxley imagined are instead working well into their seventies. But while Huxley failed to foresee the profoundly destructive force of unchecked greed—and had to assume a perhaps unobtainable world peace—he did accurately identify many of the most pressing problems of the 21st century. Eight years after the Redbook essay, Huxley was called on again to predict the future in a television interview with Mike Wallace. You can watch it in full at the top of the post.

Wallace begins in a McCarthyite vein, asking Huxley to name “the enemies of freedom in the United States.” Huxley instead discusses “impersonal forces,” returning to the problem of overpopulation and other concerns he addressed in Brave New World, such as the threat of an overly bureaucratic, technocratic society too heavily dependent on technology. Four years after this interview, Huxley published his final book, the philosophical novel Island, in which, writes Velma Lush, the evils he had warned us about, “over-population, coercive politics, militarism, mechanization, the destruction of the environment and the worship of science will find their opposites in the gentle and doomed Utopia of Pala.”

The utopia of Island—Huxley’s wife Laura told Alan Watts—is “possible and actual… Island is really visionary common sense.” But it is also a society, Huxley tragically recognized, made fragile by its unwillingness to control human behavior and prepare for war.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2016.

via Paleofuture

Related Content:

Huxley to Orwell: My Hellish Vision of the Future is Better Than Yours (1949)

Zen Master Alan Watts Discovers the Secrets of Aldous Huxley and His Art of Dying

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...

‘Kyiv Calling:’ Ukrainian Punk Band Rerecords The Clash’s Anthem as a Call to Arms

According to The Guardian, the surviving members of The Clash have given their blessing to the Ukrainian punk band, Beton, to record a new version of their 1979 classic London Calling. Recorded near the frontline of the battle in Ukraine, Kyiv Calling (above) “has lyrics that call upon the rest of the world to support the defence of the country from Russian invaders. All proceeds of what is now billed as a ‘war anthem’ will go to the Free Ukraine Resistance Movement (FURM) to help fund a shared communications system that will alert the population to threats and lobby for international support.”

You can donate to the Free Ukraine Resistance Movement here.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content

The Story Behind the Iconic Bass-Smashing Photo on the Clash’s London Calling

“Joe Strummer’s London Calling”: All 8 Episodes of Strummer’s UK Radio Show Free Online

Mick Jones Plays Three Classics by The Clash at the Public Library

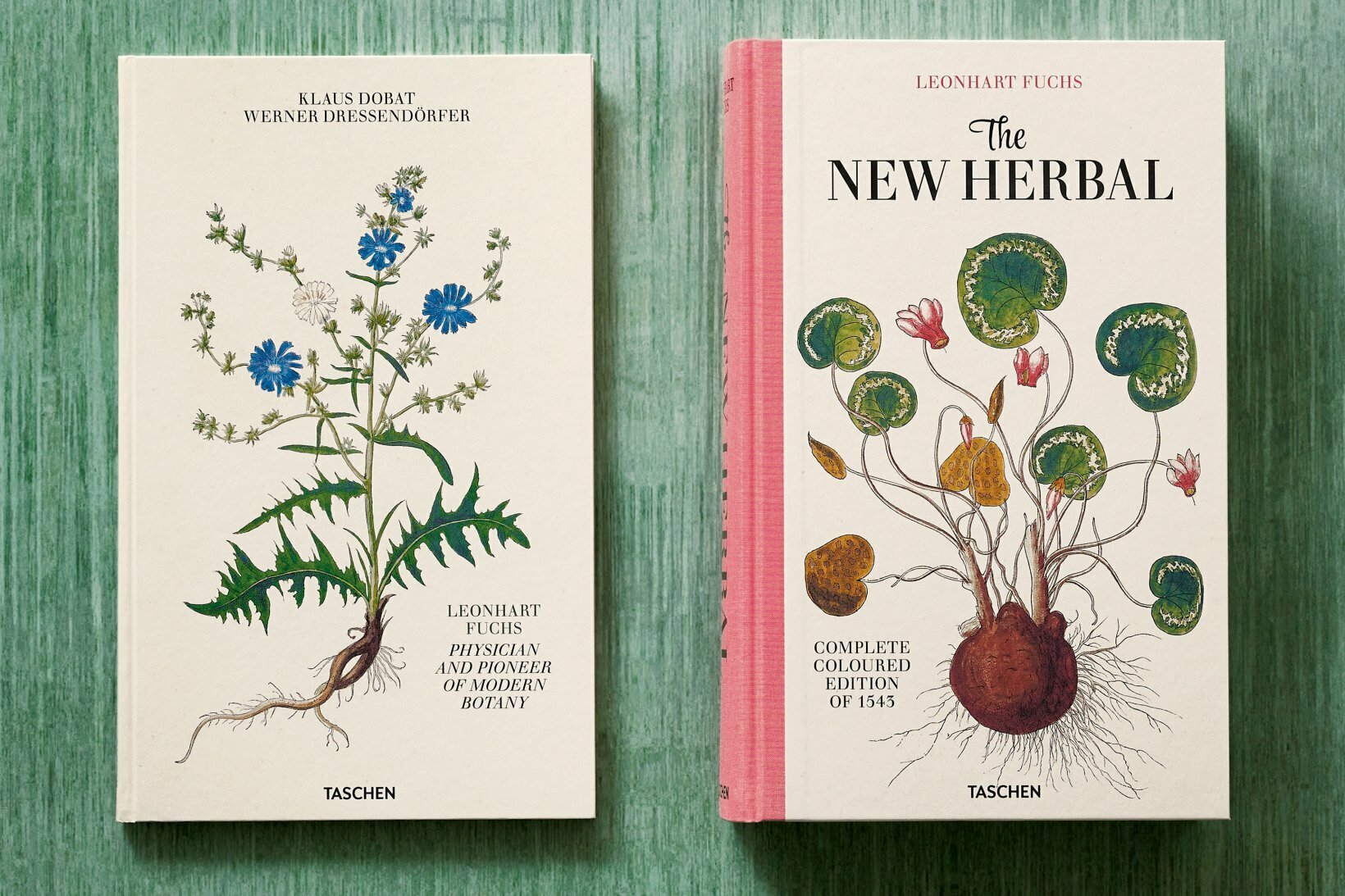

Read More...The New Herbal: A Masterpiece of Renaissance Botanical Illustrations Gets Republished in a Beautiful 900-Page Book

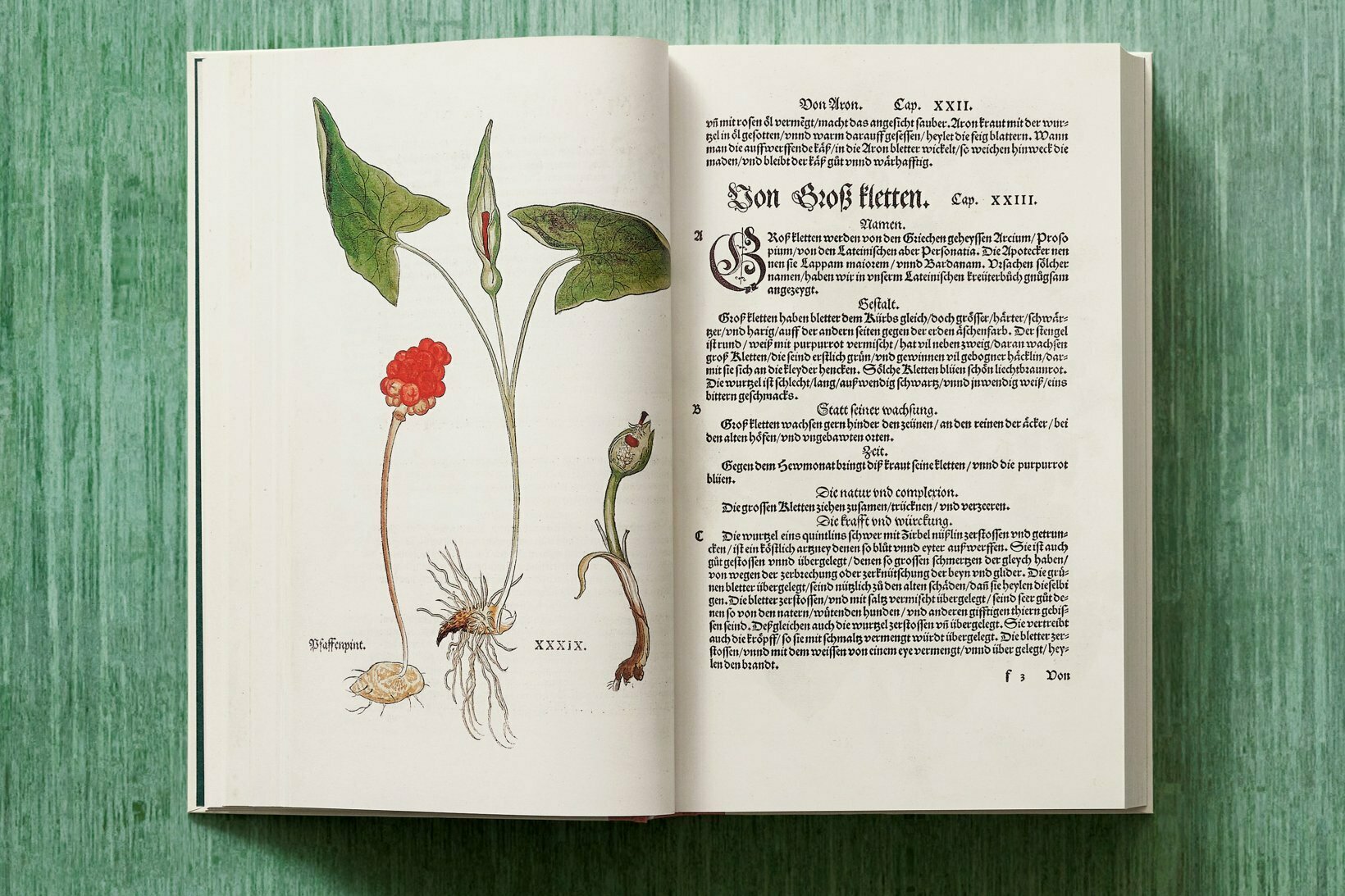

We’ve all have heard of the fuchsia, a flower (or genus of flowering plant) native to Central and South America but now grown far and wide. Though even the least botanically literate among us know it, we may have occasional trouble spelling its name. The key is to remember who the fuchsia was named for: Leonhart Fuchs, a German physician and botanist of the sixteenth century. More than 450 years after his death, Fuchs is remembered as not just the namesake of a flower, but as the author of an enormous book detailing the varieties of plants and their medicinal uses. His was a landmark achievement in the form known as the herbal, examples of which we’ve featured here on Open Culture from ninth- and eighteenth-century England.

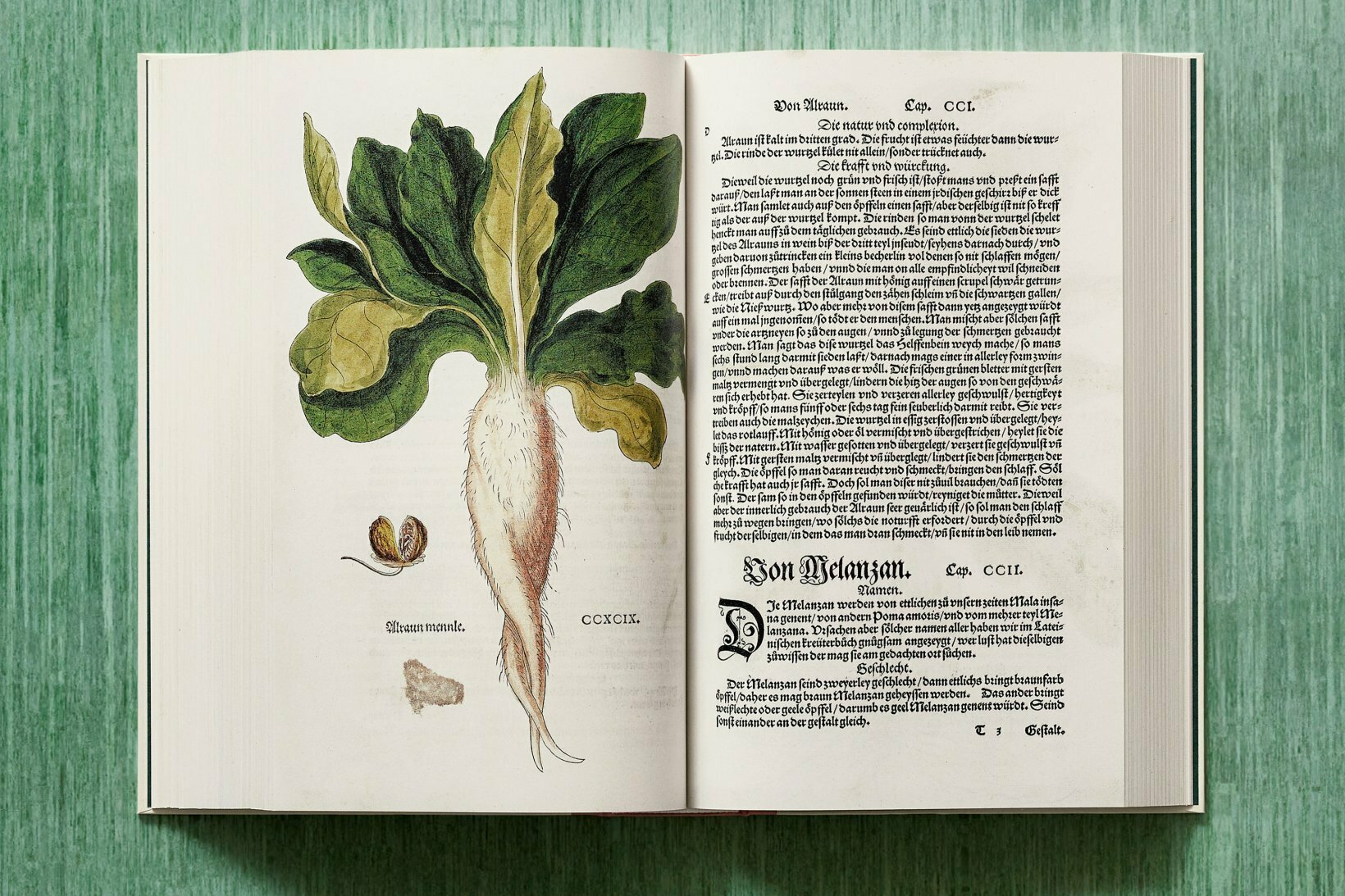

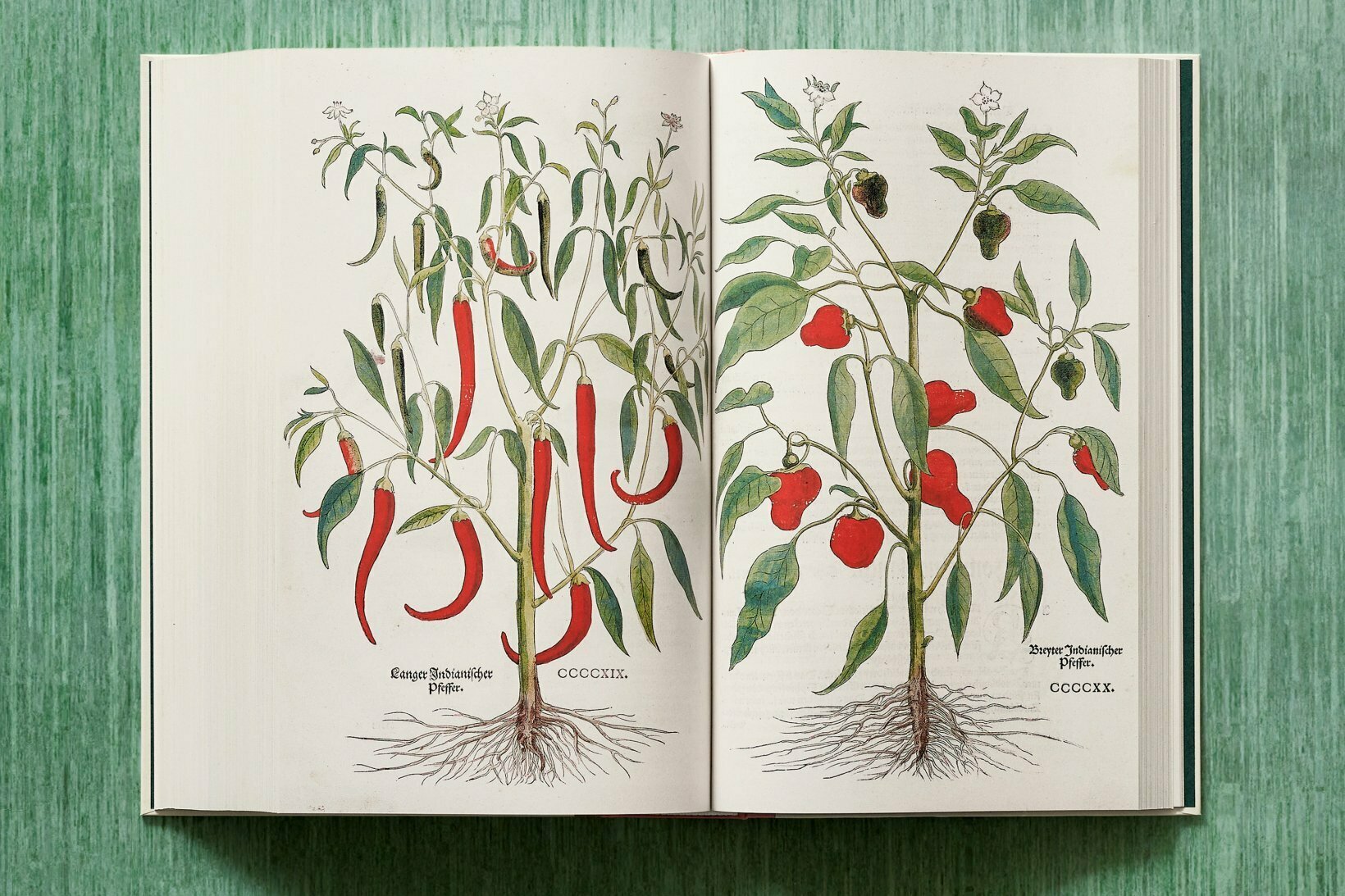

But De Historia Stirpium Commentarii Insignes, as this work was known upon its initial 1542 publication in Latin, has worn uncommonly well through the ages. Or rather, Fuchs’ personal, hand-colored original has, coming down to us in 2022 as the source for Taschen’s The New Herbal. “A masterpiece of Renaissance botany and publishing,” according to the publisher, the book includes “over 500 illustrations, including the first visual record of New World plant types such as maize, cactus, and tobacco.”

Buyers also have their choice of English, German, and French editions, each with its own translations of Fuchs’ “essays describing the plants’ features, origins, and medicinal powers.” (You can also read a Dutch version of the original online at Utrecht University Library Special Collections.)

Naturally, some of the information contained in these nearly five-century-old scientific writings will be a bit dated at this point, but the appeal of the illustrations has never dimmed. “Fuchs presented each plant with meticulous woodcut illustrations, refining the ability for swift species identification and setting new standards for accuracy and quality in botanical publications.” Over 500 of them go into the book: “Weighing more than 10 pounds,” writes Colossal’s Grace Ebert, “the nearly 900-page volume is an ode to Fuchs’ research and the field of Renaissance botany, detailing plants like the leafy garden balsam and root-covered mandrake.”

Taschen’s reproductions of these works of botanical art look to do justice to Leonhart Fuchs’ legacy, especially in the brilliance of their colors. It’s enough to reinforce the assumption that the man has received tribute not just through fuchsia the flower but fuchsia the color as well. But such a dual connection turns out to be in doubt: the color’s name derives from rosaniline hydrochloride, also known as fuchsine, originally a trade name applied by its manufacturer Renard frères et Franc. The name fuschine, in turn, derives from fuchs, the German translation of renard. The New Herbal is, of course, a work of botany rather than linguistics, but it should nevertheless stimulate in its beholders an awareness of the interconnection of knowledge that fired up the Renaissance mind.

via Colossal

Related content:

Two Million Wondrous Nature Illustrations Put Online by The Biodiversity Heritage Library

A Beautiful 1897 Illustrated Book Shows How Flowers Become Art Nouveau Designs

1,000-Year-Old Illustrated Guide to the Medicinal Use of Plants Now Digitized & Put Online

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

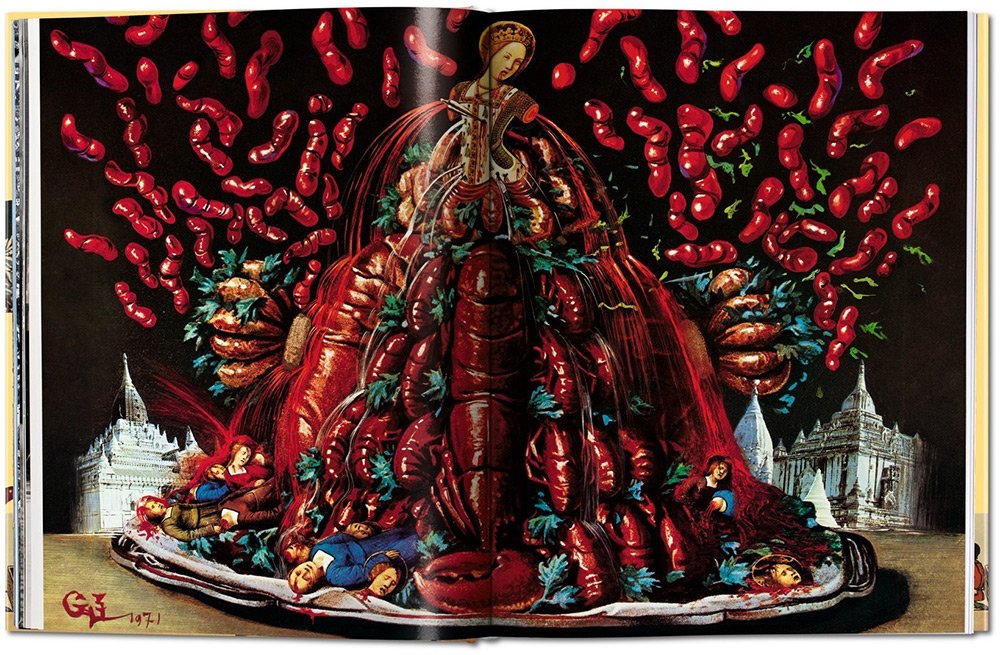

Read More...How to Actually Cook Salvador Dali’s Surrealist Recipes: Crayfish, Prawns, and Spitted Eggs

The sensual intelligence housed in the tabernacle of my palate beckons me to pay the greatest attention to food. — Salvador Dali

Looking for an easy, low-cost recipe for a quick weeknight supper?

Salvador Dali’s Bush of Crayfish in Viking Herb is not that recipe.

It’s presentation may be Surreal, but it’s not an entirely unrealistic thing to prepare as The Art Assignment’s Sarah Urist Green discovers, above.

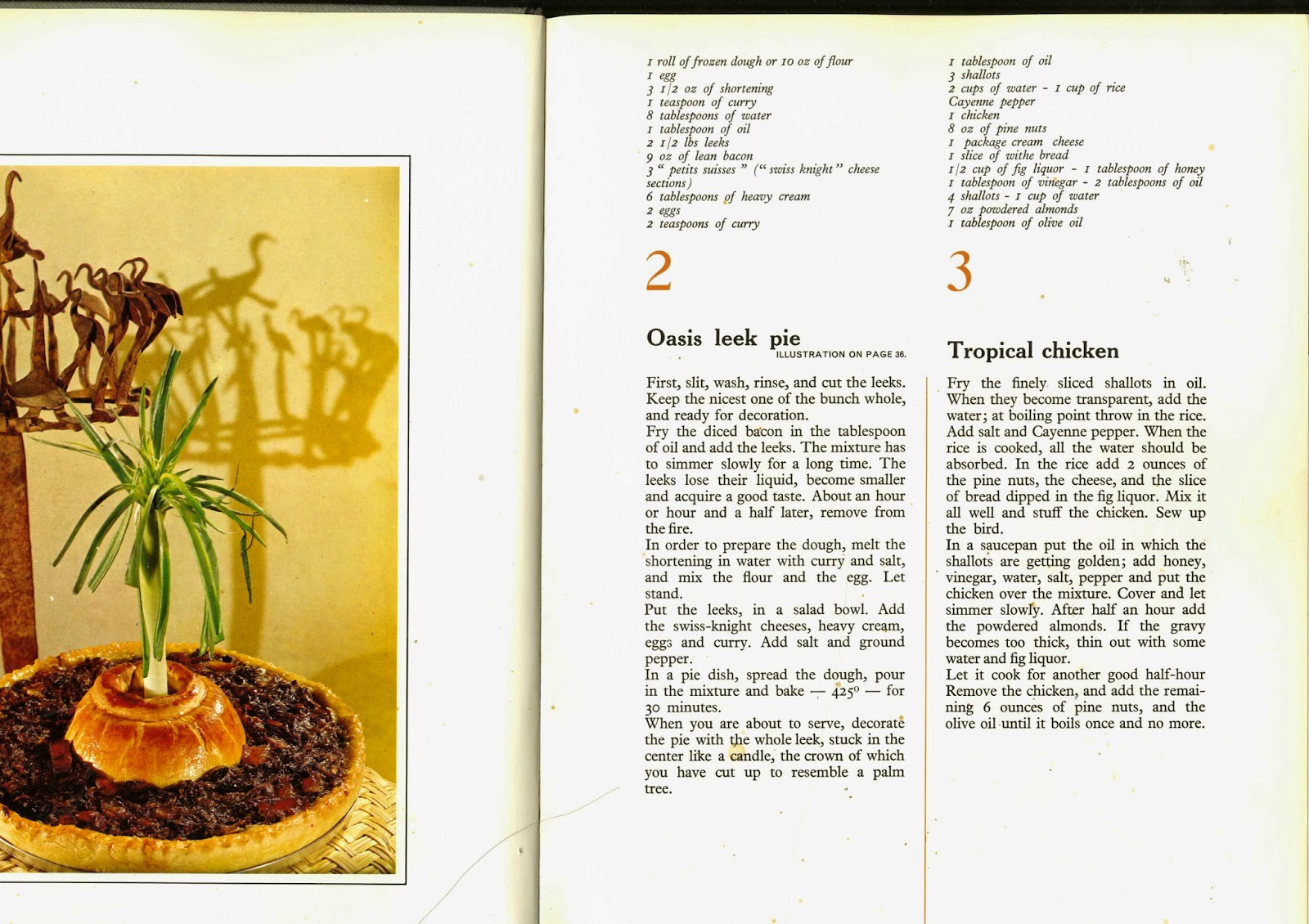

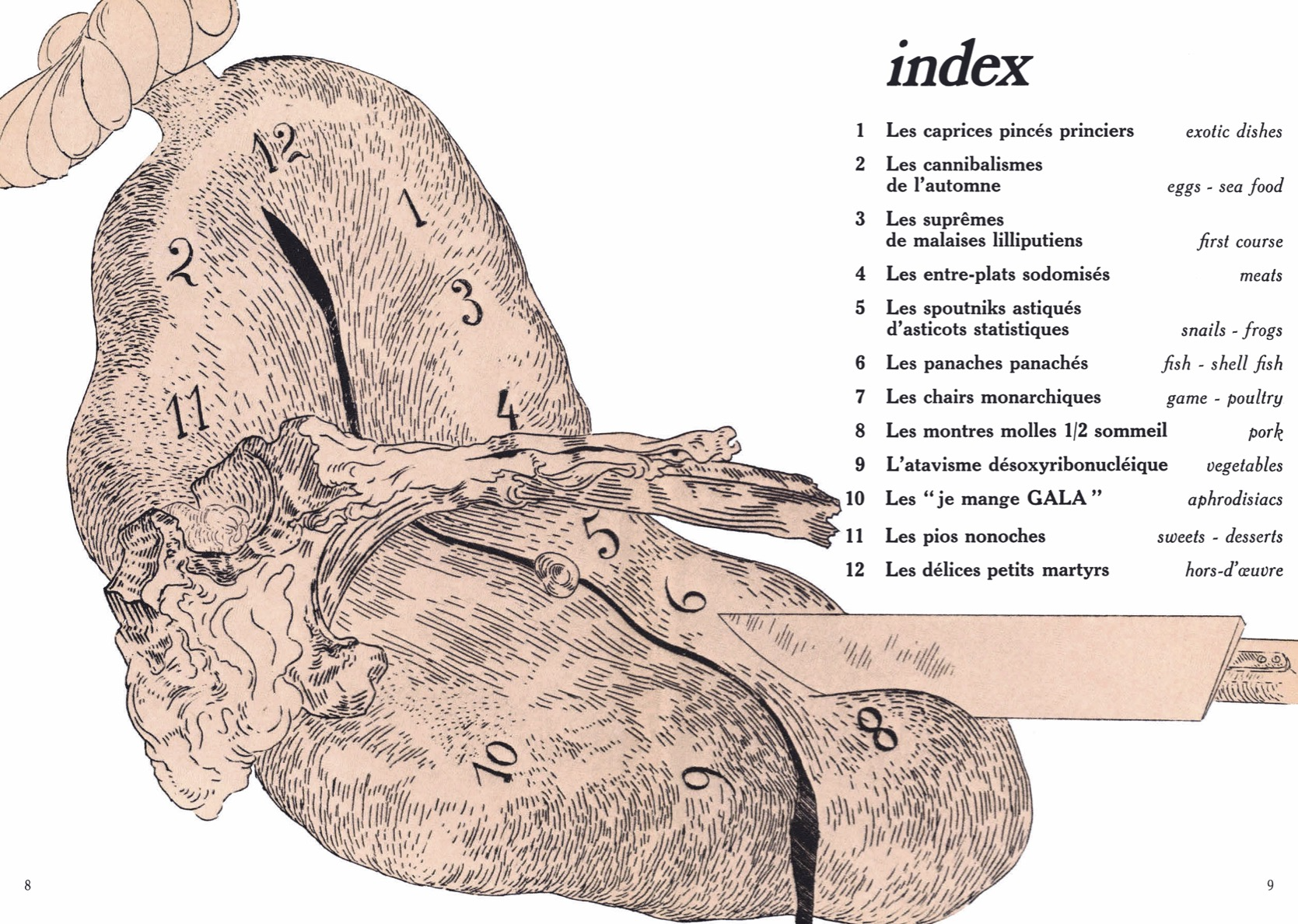

The recipe, published in Les Diners de Gala, Dali’s over-the-top cult cookery book from 1973, has pedigree.

Dali got it off a chef at Paris’ fabled Tour d’Argent, who later had second thoughts about giving away trade secrets, and balked at sharing exact measurements for the dish:

Bush of Crawfish in Viking Herbs

In order to realize this dish, it is necessary to have crawfish of 2 ounces each. Prepare the following ingredients for a broth: ‘fumet’ (scented reduced bullion) of fish, of consommé, of white wine, Vermouth, Cognac, salt, pepper, sugar and dill (aromatic herb). Poach the crawfish in this broth for 20 minutes. Let it cool for 24 hours and arrange the crawfish in a dome. Strain the broth and serve in cups.

Green, the Indianapolis Museum of Art’s former curator of contemporary art, soldiers ahead with a Styrofoam topiary cone and a boxful of Fed-Ex’ed Louisiana crayfish, masking their demise with insets of Dali works such as 1929’s Sometimes I Spit with Pleasure on the Portrait of my Mother (The Sacred Heart).

Green, well aware that some viewers may have trouble with the “brutal realities” of cooking live crustaceans, namechecks Consider the Lobster, the heavily footnoted essay wherein author David Foster Wallace ruminates over ethics at the Maine Lobster Festival.

Green may seek repentance for the sin of poaching lobsters’ freshwater cousins, but Dali, who blamed his sex-related guilt on his Catholic upbringing, was unconflicted about enjoying the “delicious little martyrs”:

If I hate that detestable degrading vegetable called spinach, it is because it is shapeless, like Liberty. I attribute capital esthetic and moral values to food in general, and to spinach in particular. The opposite of shapeless spinach, is armor. I love eating suits of arms, in fact I love all shell fish… food that only a battle to peel makes it vulnerable to the conquest of our palate.

If your scruples, schedule or savings keep you from attempting Dali’s Surreal shellfish tower, you might try enlivening a less aspirational dish with Green’s wholesome, homemade fish stock:

Devin Lytle and Jared Nunn, test driving Dali’s Cassanova cocktail and Eggs on a Spit for History Bites on Buzzfeed’s Tasty channel, seem less surefooted than Green in both the kitchen and the realm of art history, but they’re totally down to speculate as to whether or not Dali and his wife, Gala, had a “healthy relationship.”

If you can stomach their snarky, self-referential asides, you might get a bang out of hearing them dish on Dali’s revulsion at being touched, Gala’s alleged penchant for bedding younger artists, and their highly unconventional marriage.

Despite some squeamishness about the eggs’ viscousness and some reservations about the surreal amount of butter required, Lytle and Nunn’s reaction upon tasting their Dali recreation suggest that it was worth the effort:

Cassanova cocktail

• The juice of 1 orange

• 1 tablespoon bitters (Campari)

• 1 teaspoon ginger

• 4 tablespoons brandy

• 2 tablespoons old brandy (Vielle Cure)

• 1 pinch Cayenne pepper

This is quite appropriate when circumstances such as exhaustion, overwork or simply excess of sobriety are calling for a pick-me-up.

Here is a well-tested recipe to fit the bill.

Let us stress another advantage of this particular pep-up concoction is that one doesn’t have to make the sour face that usually accompanies the absorption of a remedy.

At the bottom of a glass, combine pepper and ginger. Pour the bitters on top, then brandy and “Vielle Cure.” Refrigerate or even put in the freezer.

Thirty minutes later, remove from the freezer and stir the juice of the orange into the chilled glass.

Drink… and wait for the effect.

It is rather speedy.

Your best bet for preparing Eggs on a Spit, which Lytle compares to “an herby, scrambled frittata that looks like a brain”, are contained in artist Rosanna Shalloe’s modern adaption.

What would you do if you discovered an original, autographed copy of Les Diners de Gala in the attic of your new home?

A young man named Brandon takes it to Rick Harrison’s Gold & Silver Pawn Shop, hoping it will fetch $2500.

Harrison, star of the History Channel’s Pawn Stars, gives Brandon a quick primer on the Persistence of Memory, Dali’s famous “melting clocks” painting (failing to mention that the artist insisted the clocks should be interpreted as “the Camembert of time.”)

Brandon walks with something less than the hoped for sum, and Harrison takes the book home to attempt some of the dishes. (Not, however, Bush of Crayfish in Viking Herb, which he declares, “a little creepy, even for Dali.”)

Alas, his younger relatives are wary of Oasis Leek Pie’s star ingredient and refuse to entertain a single mouthful of whole fish, baked with guts and eyes.

They’re not alone. The below newsreel suggests that comedian Bob Hope had some reservations about Dalinian Gastro Esthetics, too.

We intend to ignore those charts and tables in which chemistry takes the place of gastronomy. If you are a disciple of one of those calorie-counters who turn the joys of eating into a form of punishment, close this book at once; it is too lively, too aggressive, and far too impertinent for you. — Salvador Dali

You can purchase a copy of Taschen’s recent reissue of Les Diners de Gala online.

Related Content

Salvador Dalí’s 1973 Cookbook Gets Reissued: Surrealist Art Meets Haute Cuisine

Walk Inside a Surrealist Salvador Dalí Painting with This 360º Virtual Reality Video

Salvador Dalí’s Tarot Cards, Cookbook & Wine Guide Re-Issued as Beautiful Art Books

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...Organized Chaos!: Watch 33 Videos Showing How Saturday Night Live Gets Made Each Week

Who do you think of when you think of Saturday Night Live?

Creator Lorne Michaels?

Whoever hosted last week’s episode?

What about the guy who makes and holds the cue cards?

Wally Feresten is just one of the backstage heroes to be celebrated in Creating Saturday Night Live, a fascinating look at how the long-running television sketch show comes together every week.

Like many of those interviewed Feresten is more or less of a lifer, having come aboard in 1990 at the age of 25.

He estimates that he and his team of 8 run through some 1000 14” x 22” cards cards per show. Teleprompters would save trees, but the possibility of technical issues during the live broadcast presents too big of a risk.

This means that any last minute changes, including those made mid-broadcast, must be handled in a very hands on way, with corrections written in all caps over carefully applied white painter’s tape or, worst case scenario, on brand new cards.

(After a show wraps, its cards enjoy a second act as dropcloths for the next week’s painted sets.)

Nearly every sketch requires three sets of cue cards, so that the cast, who are rarely off book due to the frequent changes, can steal glances to the left, right and center.

As the department head, Feresten is partnered with each week’s guest host, whose lines are the only ones to be written in black. Betty White, who hosted in 2010 at the age of 88, thanked him in her 2011 autobiography.

Surely that’s worth his work-related arthritic shoulder, and the recurrent nightmares in which he arrives at Studio 8H just five minutes before showtime to find that all 1000 cue cards are blank.

Costumes have always been one of Saturday Night Live’s flashiest pleasures, running the gamut from Coneheads and a rapping Cup o’Soup to an immaculate recreation of the white pantsuit in which Vice President Kamala Harris delivered her victory speech a scant 3 hours before the show aired.

“A costume has a job,” wardrobe supervisor Dale Richards explains:

It has to tell a story before (the actors) open their mouth…as soon as it comes on camera, it should give you so much backstory.

And it has to cleave to some sort of reality and truthfulness, even in a sketch as outlandish as 2017’s Henrietta & the Fugitive, starring host Ryan Gosling as a detective in a film noir style romance. The gag is that the dame is a chicken (cast member Aidy Bryant.)

Richards cites actress Bette Davis as the inspiration for the chicken’s look:

Because you’re not going to believe it if the detective couldn’t actually fall in love with her. She has to be very feminine, so we gave her Bette Davis bangs and long eyelashes and a beautiful bonnet, so the underpinnings were very much like an actress in a movie, although she did have a chicken costume on.

The number of quick costume changes each performer must make during the live broadcast helps determine the sketches’ running order.

Some of the breakneck transformations are handled by Richards’ sister, Donna, who once beat the clock by piggybacking host Jennifer Lopez across the studio floor to the changing area where a well-coordinated crew swished her out of her opening monologue’s skintight dress and skyscraper heels and into her first costume.

That’s one example of the sort of traffic the 4‑person crane camera crew must battle as they hurtle across the studio to each new set. Camera operator John Pinto commands from atop the crane’s counterbalanced arm.

Those swooping crane shots of the musical guests, opening monologue and goodnights (see below) are a Saturday Night Live tradition, a part of its iconic look since the beginning.

Get to know other backstage workers and how they contribute to this weekly high wire act in a 33 episode Creating Saturday Night playlist, all on display below:

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Related Content

The Stunt That Got Elvis Costello Banned From Saturday Night Live

Saturday Night Live’s Very First Sketch: Watch John Belushi Launch SNL in October, 1975

Read More...Nikola Tesla’s Predictions for the 21st Century: The Rise of Smart Phones & Wireless, The Demise of Coffee & More (1926/35)

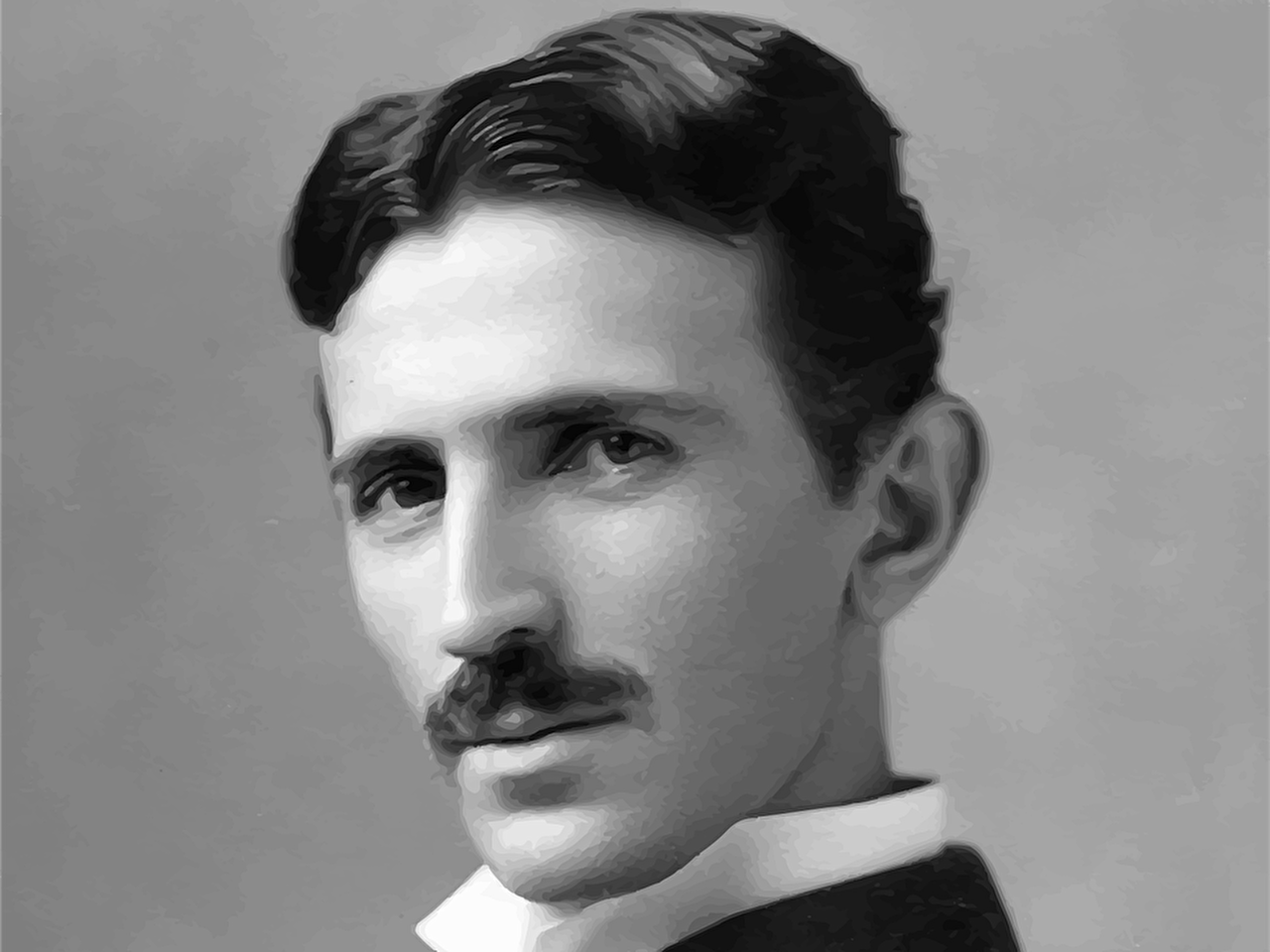

The fate of the visionary is to be forever outside of his or her time. Such was the life of Nikola Tesla, who dreamed the future while his opportunistic rival Thomas Edison seized the moment. Even now the name Tesla conjures seemingly wildly impractical ventures, too advanced, too expensive, or far too elegant in design for mass production and consumption. No one better than David Bowie, the pop artist of possibility, could embody Tesla’s air of magisterial high seriousness on the screen. And few were better suited than Tesla himself, perhaps, to extrapolate from his time to ours and see the technological future clearly.

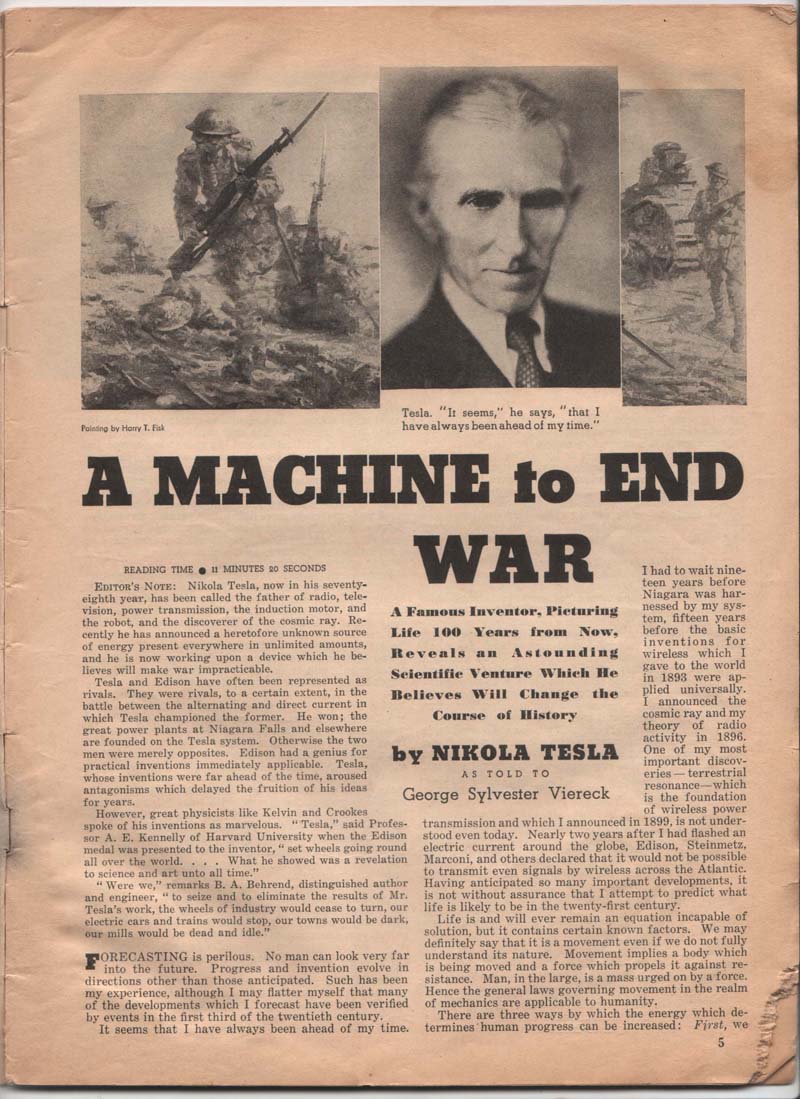

Of course, this image of Tesla as a lone, heroic, and even somewhat tragic figure who fell victim to Edison’s designs is a bit of a romantic exaggeration. As even the editor of a 1935 feature interview piece in the now-defunct Liberty magazine wrote, Tesla and Edison may have been rivals in the “battle between alternating and direct current…. Otherwise the two men were merely opposites. Edison had a genius for practical inventions immediately applicable. Tesla, whose inventions were far ahead of the time, aroused antagonisms which delayed the fruition of his ideas for years.” One can in some respects see why Tesla “aroused antagonisms.” He may have been a genius, but he was not a people person, and some of his views, though maybe characteristic of the times, are downright unsettling.

In the lengthy Liberty essay, “as told to George Sylvester Viereck” (a poet and Nazi sympathizer who also interviewed Hitler), Tesla himself makes the pronouncement, “It seems that I have always been ahead of my time.” He then goes on to enumerate some of the ways he has been proven right, and confidently lists the characteristics of the future as he sees it. No one likes a know-it-all, but Tesla refused to compromise or ingratiate himself, though he suffered for it professionally. And he was, in many cases, right. Many of his 1935 predictions in Liberty are still too far off to measure, and some of them will seem outlandish, or criminal, to us today. But some still seem plausible, and a few advisable if we are to make it another 100 years as a species. Tesla’s predictions include the following, which he introduces with the disclaimer that “forecasting is perilous. No man can look very far into the future.”

- “Buddhism and Christianity… will be the religion of the human race in the twenty-first century.”

- “The year 2100 will see eugenics universally established.” Tesla went on to comment, “no one who is not a desirable parent should be permitted to produce progeny. A century from now it will no more occur to a normal person to mate with a person eugenically unfit than to marry a habitual criminal.”

- “Hygiene, physical culture will be recognized branches of education and government. The Secretary of Hygiene or Physical Culture will be far more important in the cabinet of the President of the United States who holds office in the year 2025 than the Secretary of War.” Along with personal hygiene, Tesla included “pollution” as a social ill in need of regulation.

- “I am convinced that within a century coffee, tea, and tobacco will be no longer in vogue. Alcohol, however, will still be used. It is not a stimulant but a veritable elixir of life.”

- “There will be enough wheat and wheat products to feed the entire world, including the teeming millions of China and India.” (Tesla did not foresee the anti-gluten mania of the 21st century.)

- “Long before the next century dawns, systematic reforestation and the scientific management of natural resources will have made an end of all devastating droughts, forest fires, and floods. The universal utilization of water power and its long-distance transmission will supply every household with cheap power.” Along with this optimistic prediction, Tesla foresaw that “the struggle for existence being lessened, there should be development along ideal rather than material lines.”

Tesla goes on to predict the elimination of war, “by making every nation, weak or strong, able to defend itself,” after which war chests would be diverted to funding education and research. He then describes—in rather fantastical-sounding terms—an apparatus that “projects particles” and transmits energy, enabling not only a revolution in defense technology, but “undreamed of results in television.” Tesla diagnoses his time as one in which “we suffer from the derangement of our civilization because we have not yet completely adjusted ourselves to the machine age.” The solution, he asserts—along with most futurists, then and now—“does not lie in destroying but in mastering the machine.” As an example of such mastery, Tesla describes the future of “automatons” taking over human labor and the creation of “a thinking machine.”

Matt Novak at the Smithsonian has analyzed many of Tesla’s claims, interpreting his predictions about “hygiene and physical culture” as a foreshadowing of the EPA and discussing Tesla’s work in robotics (“Today,” Tesla proclaimed, “the robot is an accepted fact”). The Liberty article was not the first time Tesla had made large-scale, public predictions about the century to come and beyond. In 1926, Tesla gave an interview to Collier’s magazine in which he more or less accurately foresaw smartphones and wireless telephony and computing:

When wireless is perfectly applied the whole earth will be converted into a huge brain, which in fact it is…. We shall be able to communicate with one another instantly, irrespective of distance. Not only this, but through television and telephony we shall see and hear one another as perfectly as though were face to face, despite intervening distances of thousands of miles; and the instruments through which we shall be able to do this will be amazingly simple compared with our present telephone. A man will be able to carry one in his vest pocket.

Telsa also made some odd predictions about fuel-less passenger flying machines “free from any limitations of the present airplanes and dirigibles” and spouted more of the scary stuff about eugenics that had come to obsess him late in life. Additionally, Tesla saw changing gender relations as the precursor of a coming matriarchy. This was not a development he characterized in positive terms. For Tesla, feminism would “end in a new sex order, with the female as superior.” (As Novak notes, Tesla’s misgivings about feminism have made him a hero to the so-called “men’s rights” movement.) While he fully granted that women could and would match and surpass men in every field, he warned that “the acquisition of new fields of endeavor by women, their gradual usurpation of leadership, will dull and finally dissipate feminine sensibilities, will choke the maternal instinct, so that marriage and motherhood may become abhorrent and human civilization draw closer and closer to the perfect civilization of the bee.”

It seems to me that a “bee civilization” would appeal to a eugenicist, except, I suppose, Tesla feared becoming a drone. Although he saw the development as inevitable, he still sounds to me like any number of current politicians who argue that society should continue to suppress and discriminate against women for their own good and the good of “civilization.” Tesla may be an outsider hero for geek culture everywhere, but his social attitudes give me the creeps. While I’ve personally always liked the vision of a world in which robots do most the work and we spend most of our money on education, when it comes to the elimination of war, I’m less sanguine about particle rays and more sympathetic to the words of Ivor Cutler.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2015.

via Smithsonian/Paleofuture

Related Content:

In 1900, Ladies’ Home Journal Publishes 28 Predictions for the Year 2000

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...