As much as it is about every part of Dublin that ever passed by James Joyce’s once-young eyes, Ulysses is also a book about books, and about writing and speech—as mythic invocation, as seduction, chatter, and rhetoric, fulsome and empty. Words—two-faced, like open books—carry with them at least two senses, the meaning of their present utterance, and the verso shades of history. This is at least partly the import of Joyce’s mythical method, as it is that of all expositors of ancient texts, from preachers and theologians to literary critics. It seems particularly significant, then, that the passage Joyce chose for the one and only recording of a reading from Ulysses comes from the “Aeolus” episode, which parodies Odysseus and his companions’ encounter with the god of wind.

Joyce sets the scene in the newspaper offices of the Freeman’s Journal, epitome of writing in the present tense, where reporters and editors give puffed-up speeches punctuated by reductive, pithy headlines. Amidst this business, erudite professor MacHugh and Stephen Dedalus wax literary and historical, making connections. MacHugh recites “the finest display of oratory” he ever heard—a defense of the revival of the Irish language that compares the Irish people to Moses and the ancient Hebrews spurning the seductions of an oppressive empire in the person of an Egyptian high priest: Vagrants and daylabourers are you called: the world trembles at our name.

Joyce recorded the passage in 1924 at the urging of Shakespeare and Company founder Sylvia Beach, who persuaded the HMV gramophone studio in Paris to make the record, under the provision that she would finance it and that the studio’s name would appear nowhere on the product. Ulysses, recall, was in many places under a ban for obscenity (not lifted in the U.S. until 1933 by Judge John Woolsey). The recording session was painful for Joyce, who needed two attempts on two separate days to complete it, plagued as he was by his failing eyes. And yet Joyce, Beach wrote in her notes, “was anxious to have the recording made… He had made up his mind, he told me, that this would be his only reading from Ulysses… it is more, one feels, than mere oratory.” You can read the speech here while listening to Joyce read above. Beach called Joyce’s reading a “wonderful performance.” “I never hear it,” she wrote, “without being deeply moved.”

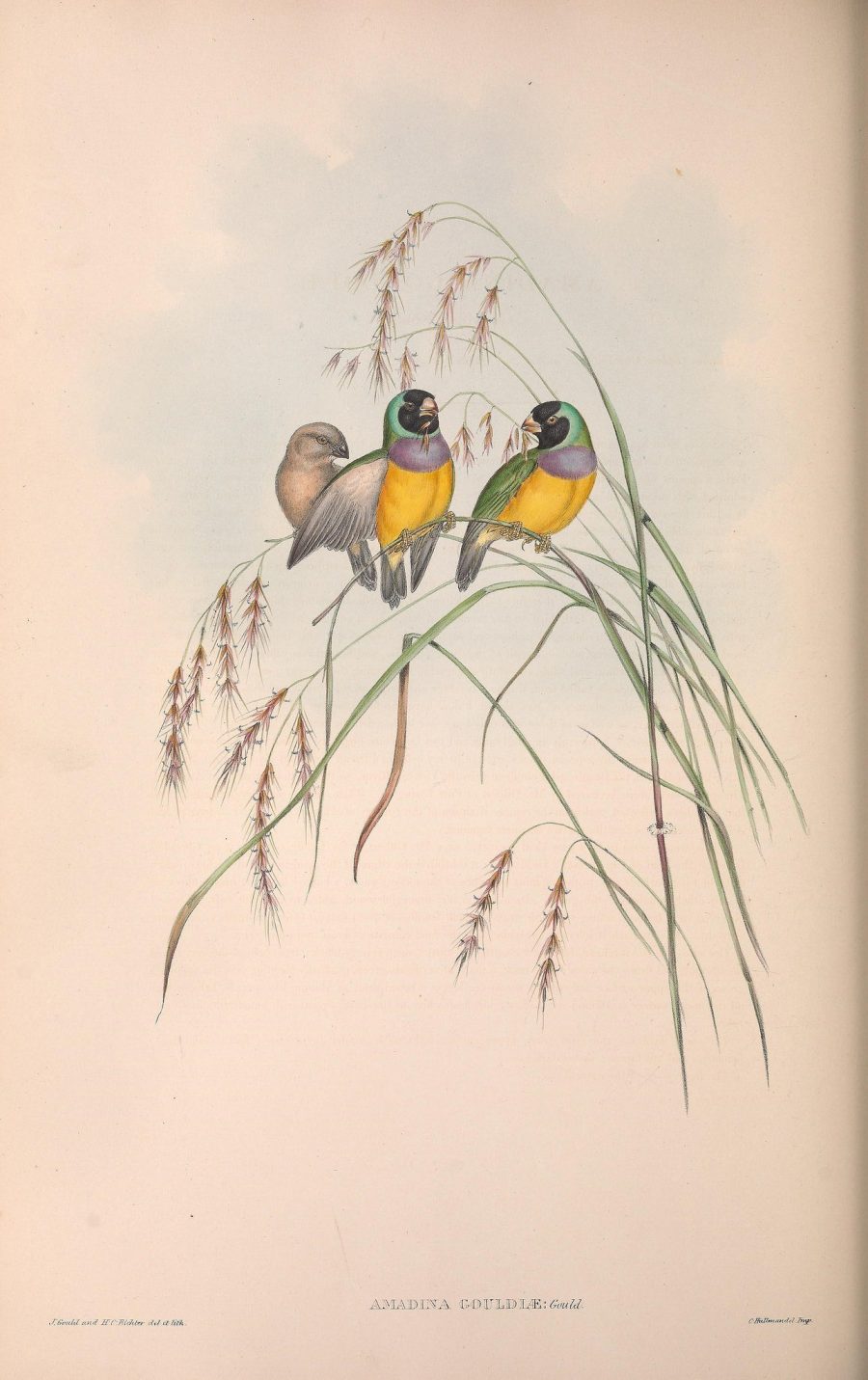

While Beach may have been satisfied with the recording, her friend, linguist C.K. Ogden pronounced it “very bad,” meaning, writes Beach, “it was not a success technically” (though it was not, in any case, “at all a commercial venture”). You will notice this immediately as you struggle to hear Joyce’s muted reading. Anxious to preserve his voice in a clearer document, Ogden captured Joyce reading from Finnegans Wake five years later at the studio of the Ornithological Society in Cambridge (he boasted of owning “the two biggest recording machines in the world”). By this time, Joyce’s eyesight had almost completely dimmed. Ogden photographed the text and enlarged it so that the letters were a half-inch tall, yet Joyce still could barely make them out and “supposedly needed someone to whisper along” (Beach, who was not present, imagined he must have known the passage by heart).

Joyce chose to read from the “Anna Livia Plurabelle” section of the experimental text—a passage “overflowing,” writes Mental Floss, with “allusions to the world’s rivers.” He reads in the voice of an old washerwoman, and begins with a most succinct statement of the temporal dimensions of language: “I told you every telling has a tailing.” Where Ulysses foregrounds literary history, Finnegans Wake dives deep into geologic time, and privileges the oral over the written. These are the only two recordings Joyce ever made, and they surely mark what were for him central locations in both books, though he also chose them for their ease of reading aloud and, perhaps, memorizing.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2014.

Related Content:

James Joyce, With His Eyesight Failing, Draws a Sketch of Leopold Bloom (1926)

Sylvia Beach Tells the Story of Founding Shakespeare and Company, Publishing Joyce’s Ulysses, Selling Copies of Hemingway’s First Book & More (1962)

Hear All of Finnegans Wake Read Aloud: A 35 Hour Reading

What Makes James Joyce’s Ulysses a Masterpiece: Great Books Explained

Virginia Woolf on James Joyce’s Ulysses, “Never Did Any Book So Bore Me.” Shen Then Quit at Page 200

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC.