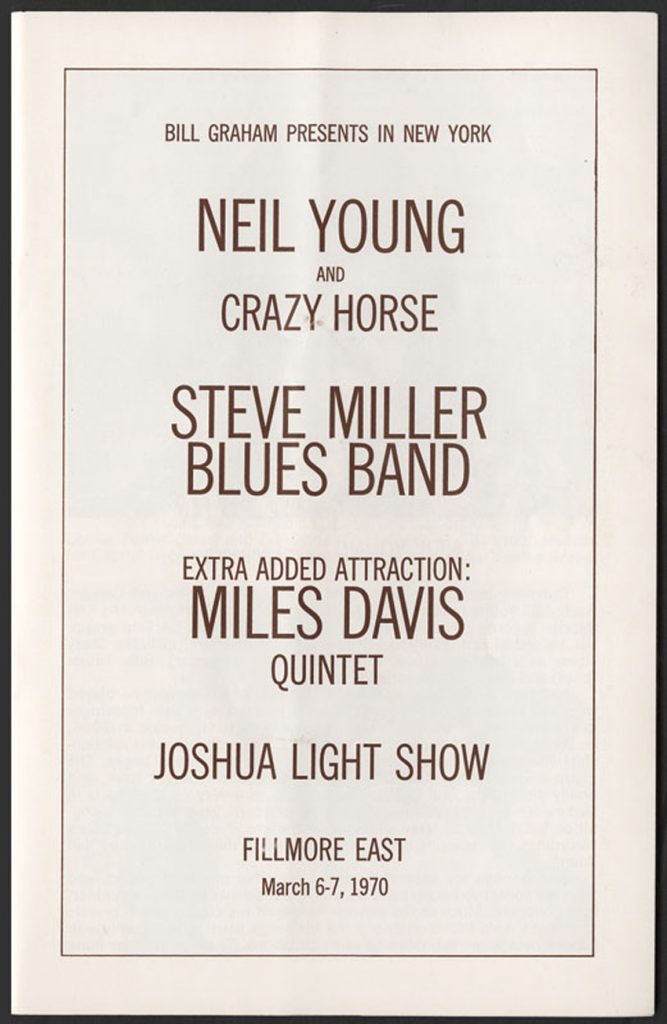

The story, the many stories, of Miles Davis as an opening act for several rock bands in the 1970s makes for fascinating reading. Before he blew the Grateful Dead’s minds as their opening act at the Fillmore West in April 1970 (hear both bands’ sets here), Davis and his all-star Quintet—billed as an “Extra Added Attraction”—did a couple nights at the Fillmore East, opening for Neil Young and Crazy Horse and The Steve Miller Band in March of 1970. The combination of Young and Davis actually seems to have been rather unremarkable, but there is a lot to say about where the two artists were individually.

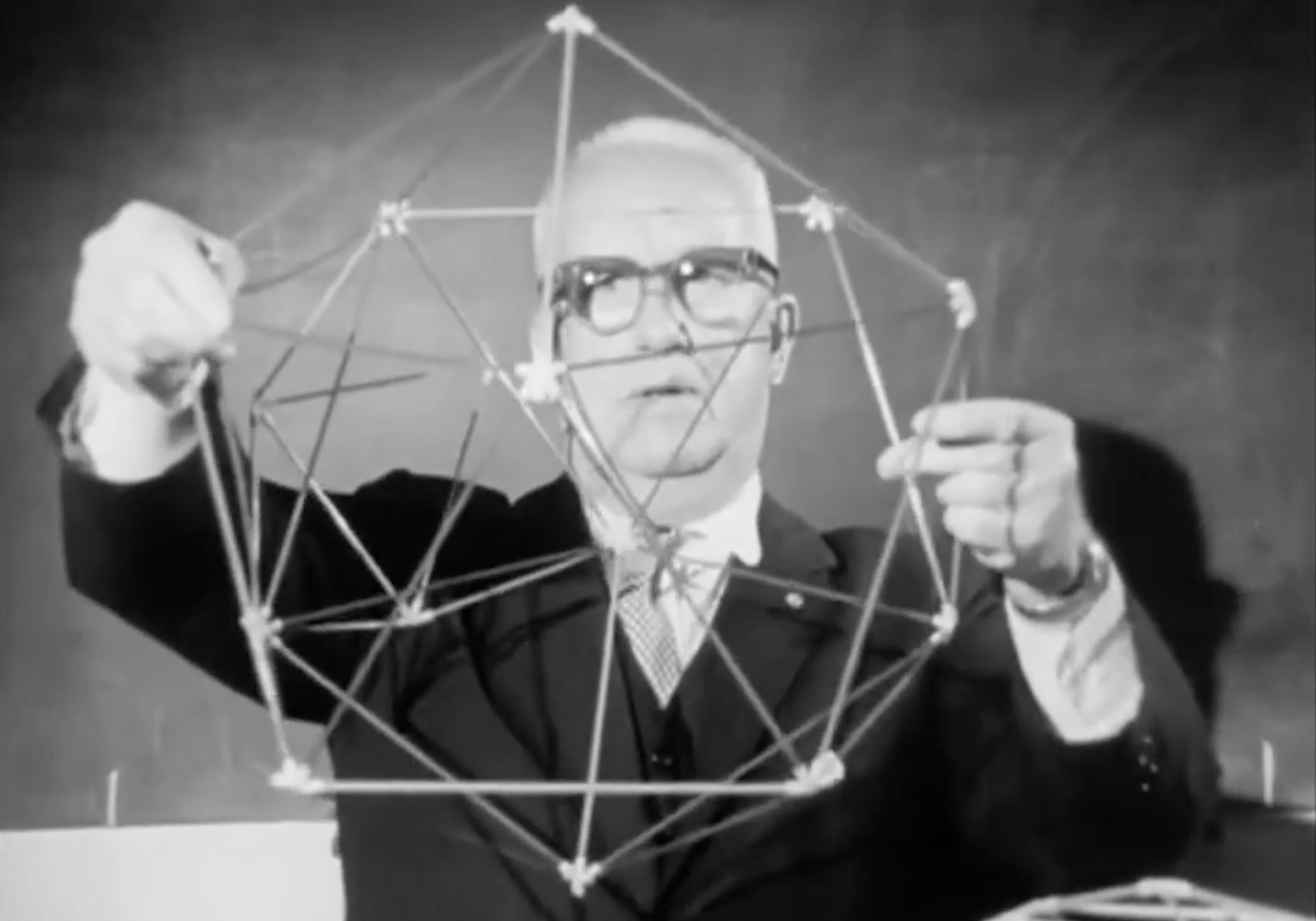

Nate Chinen in At Length describes their meeting as a “minimum orbit intersection distance”—the “closest point of contact between the paths of two orbiting systems.” Both artists were “in the thrall of reinvention,” Young moving away from the smoothness of CSNY and into free-form anti-virtuosity with Crazy Horse; Davis toward virtuosity turned back into the blues.

Miles, suggested jazz writer Greg Tate, was “bored fiddling with quantum mechanics and just wanted to play the blues again.” The story of Davis and Young at the Fillmore East is best told by listening to the music both were making at the time. Hear “Cinnamon Girl” below and the rest of Neil Young and Crazy Horse’s incredible set here. The band had just released their beautifully ragged Everybody Knows this is Nowhere.

When it comes to the meeting of Davis and Steve Miller, the story gets juicier, and much more Miles: the difficult performer, not the impossibly cool musician. (It sometimes seems like the word “difficult” was invented to describe Miles Davis.) The trumpeter’s well-earned egotism lends his legacy a kind of rakish charm, but I don’t relish the positions of those record company executives and promoters who had to wrangle him, though many of them were less than charming individuals themselves. Columbia Records’ Clive Davis, who does not have a reputation as a pushover, sounds alarmed in his recollection of Miles’ reaction after he forced the trumpeter to play the Fillmore dates to market psychedelic jazz-funk masterpiece Bitches Brew to white audiences.

According to John Glatt, Davis remembers that Miles “went nuts. He told me he had no interest in playing for ‘those fu*king long-haired kids.’” Particularly offended by The Steve Miller Band, Davis refused to arrive on time to open for an artist he deemed “a sorry-ass cat,” forcing Miller to go on before him. “Steve Miller didn’t have his shit going for him,” remembers Davis in his expletive-filled autobiography, “so I’m pissed because I got to open for this non-playing motherfu*ker just because he had one or two sorry-ass records out. So I would come late and he would have to go on first and then when we got there, we smoked the motherfu*king place, and everybody dug it.” There is no doubt Davis and Quintet smoked. Hear them do “Directions” above from an Early Show on March 6, 1970.

“Directions,” from unreleased tapes, is as raw as they come, “the intensity,” writes music blog Willard’s Wormholes, “of a band that sounds like they were playing at The Fillmore to prove something to somebody… and did.” The next night’s performances were released in 2001 as It’s About That Time. Hear the title track above from March 7th. You can also stream more on YouTube. As for The Steve Miller Blues Band? We have audio of their performance from that night as well. Hear it below. It’s inherently an unfair comparison between the two bands, not least because of the vast difference in audio quality. But as for whether or not they sound like “sorry-ass cats”… well, you decide.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2015.

Related Content:

The Night When Miles Davis Opened for the Grateful Dead in 1970: Hear the Complete Recordings

In 1969 Telegram, Jimi Hendrix Invites Paul McCartney to Join a Super Group with Miles Davis

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC.