If you’re looking for free outdoor activities to pull you from the digital realm, may we recommend mudlarking?

Lara Maiklem, author of Mudlarking: Lost and Found on the River Thames and A Field Guide to Larking, has developed a keen eye in the 20 years she’s been scavenging historic detritus from the foreshore of the Thames at low tide.

I never use a metal detector and I often walk little more than a mile in 5 hours, yet I can travel 2,000 years back in time through the objects that are revealed by the tide. Prehistoric flint tools, medieval pilgrim badges, Tudor shoes, Georgian wig curlers and Victorian pottery, ordinary objects left behind by the ordinary people who made London what it is today.

As she says in the short film above, her first find has become one of her most common — a clay pipe fragment.

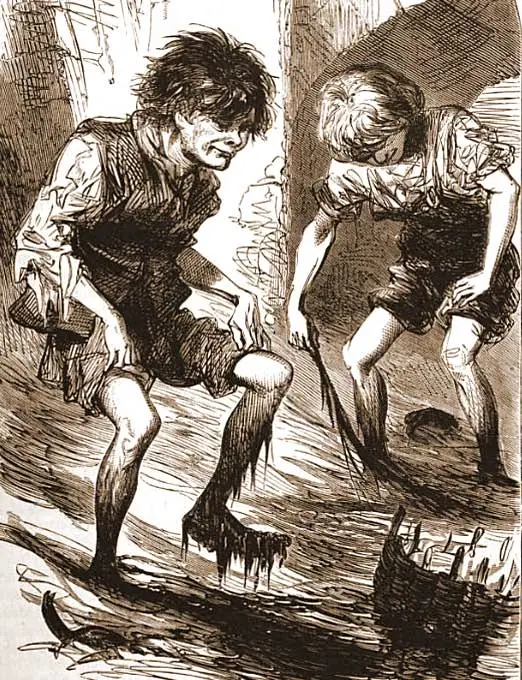

The term mudlark was invented to describe the poverty stricken Victorians who scoured the foreshore for copper, wire, and other items with resale value, as well as things they could clean off and use themselves.

Today’s mudlarks are primarily history buffs and amateur archeologists.

The hobby has become so popular that The Port of London Authority, which controls the Thames waterway along with the Crown Estate, has started to require foreshore permits of all prospective debris hunters.

Permitted mudlarks can claim as souvenirs however many Victorian clay pipes and blue and white pottery shards they dig up, but are legally obliged by the Portable Antiquities Scheme to report items of potentially greater historic and monetary value — i.e. Treasure — to a museum-trained Finds Liason Officer:

- Any metallic object, other than a coin, provided that at least 10 per cent by weight of metal is precious metal (that is, gold or silver) and that it is at least 300 years old when found. If the object is of prehistoric date it will be Treasure provided any part of it is precious metal.

- Any group of two or more metallic objects of any composition of prehistoric date that come from the same find (see note below).

- Two or more coins from the same find provided they are at least 300 years old when found and contain 10 per cent gold or silver (if the coins contain less than 10 per cent of gold or silver there must be at least ten of them). Only the following groups of coins will normally be regarded as coming from the same find: Hoards that have been deliberately hidden; Smaller groups of coins, such as the contents of purses, that may been dropped or lost; Votive or ritual deposits.

- Any object, whatever it is made of, that is found in the same place as, or had previously been together with, another object that is Treasure.

How did all this historic refuse come to be in the Thames? Maiklem told Collectors Weekly that there are many reasons:

Obviously, it’s been used as a rubbish dump. It was a useful place to chuck your household waste. It was essentially a busy highway, so people accidentally dropped things and lost things as they traveled on it. Of course, people also lived right up against it. London was centered on the Thames so houses were all along it, and there was all this stuff coming out of the houses and off the bridges. It was the biggest port in the world in the 18th century, so there was all the shipbuilding and industry going on.

And then of course, there’s the rubbish that was used to build up the foreshore and create barge beds. The riverbed in its natural state is a V shape, so they had to build up the sides next to the river wall to make them flatter so the flat-bottom barges could rest there at low tide. They did that by pouring rubbish and building spoil and kiln waste, anything they could find—industrial waste, domestic waste. When they dug into the ground further up, they’d bring the spoil down and use it to build up the foreshore, and cap it off with a layer of chalk, which was soft and didn’t damage the bottom of the barges.

One of the reasons we’re finding so much in the river now is because there’s so much erosion. While it was a “working river,” these barge beds were patched up and the revetments, or the wooden walls that held them in, were repaired when they broke. But now, they’re being left to fall apart, and these barge beds are eroding as the river is getting busier with river traffic.

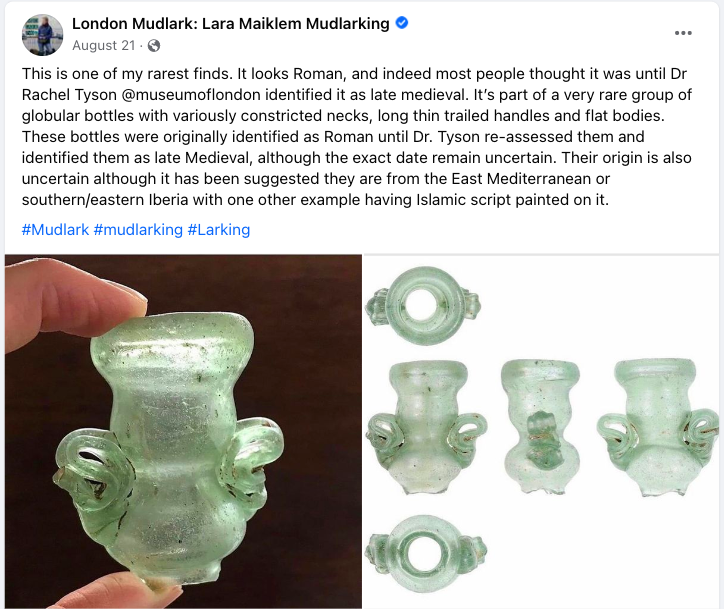

There are numerous social media groups where modern mudlarks can proudly share their finds, and seek assistance in identifying strange or fragmented objects.

Maiklem’s London Mudlark Facebook page is an education in and of itself, a reflection of her abiding interest in the historic significance of the items she truffles up.

Witness the pewter buckle plate dating to the 14th or 15th-century that she spotted on the foreshore in late November, turned over to her Finds Liaison Officer and researched with the help of historic pewter craftsman Colin Torode:

Prior to c.1350 pewter belt fittings seem to have been rather rare, although a London Girdlers’ Guild Charter of 1321 which banned the use of pewter belt fittings does show that the metal was certainly in use. In 1344 the Girdlers’ guild again reiterated the ban on what they felt were inferior metals such as pewter, tin and lead. In 1391 however, a statute recognized that these metals had been in use for some time and that their use could continue without restriction

This ornate plate would have had a separate buckle frame attached to it and is probably a cheaper copy of the more upmarket copper alloy or silver versions that were produced at the time. Although the the openwork design is similar to those found in in furniture or church screens, it’s not religious or pilgrim related.

Maiklem also challenges fans to play along from home with “spot the find” videos for such items as a Tudor clothes hook, Georgian cufflink, and a German salt glazed, stoneware bottle’s neck embossed with a human face.

She also reminds would be mudlarks to always wear gloves as it’s not all medieval thimbles, WWI medals and 16th-century boxwood combs, beautifully preserved by the Thames’ anaerobic mud.

The river also spews up plenty of drowned rats, flushing them out with the sewage after a heavy rain. Other potential hazards include hypodermic needles and broken glass.

In addition to such safety precautions as gloves, sturdy footwear, and remaining mindful of incoming tides, Maiklem advises novice mudlarks to look for straight lines and perfect circles — “the things that nature doesn’t make.”

It takes practice and patience to develop a skilled eye, but don’t get discouraged if your first outings don’t yield the sort of jaw dropping discoveries Maiklem has made — an intact glass Victorian sugar crusher, a 16th-century child’s leather shoe and Roman era pottery shards galore.

Sometimes even plastic comes with a compelling story.

I’m still feeling quite giddy over this bit of plastic. I came to Cornwall this week to write and to beachcomb. I hoped I might find a small piece of Lost Lego, but I wasn’t holding out much hope. Calm weather means less plastic: good for the beach, bad for the Lego looker. Then I found this wedged between two boulders. It’s one of the black octopuses from the Lego spill of 1997 when, 20 miles from Land’s End, a huge wave hit the cargo ship Tokio Express. It tilted 45 degrees and 62 containers slid into the water. One container was filled with nearly 5 million pieces of Lego, much of which was sea themed. Little scuba tanks, flippers, octopuses, cutlasses, life rafts, spear guns, dragons and octopuses like this still wash up on the beaches of Cornwall and further afield.

Stay abreast of Lara Maiklem’s mudlarking finds here.

Try your hand at mudlarking the Thames in person, during a guided tour with the Thames Explorer Trust.

Related Content

Prize-Winning Animation Lets You Fly Through 17th Century London

- Ayun Halliday is a mudlarking newbie, the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.