In Christmases past, we featured Charles Dickens’ hand-edited copy of his beloved 1843 novella A Christmas Carol. He did that hand editing for the purposes of giving public readings, a practice that, in his time, “was considered a desecration of one’s art and a lowering of one’s dignity.” That time, however, has gone, and many of the most prestigious writers alive today take the reading aloud of their own work to the level of art, or at least high entertainment, that Dickens must have suspected one could. Some writers even do a bang-up job of reading other writers’ work: modern master storyteller Neil Gaiman gave us a dose of that when we featured his recitation of Lewis Carroll’s “Jabberwocky” from memory. Today, however, comes the full meal: Gaiman’s telling of A Christmas Carol straight from that very Dickens-edited reading copy.

Gaiman read to a full house at the New York Public Library, an institution known for its stimulating events, holiday-themed or otherwise. But he didn’t have to hold up the afternoon himself; taking the stage before him, BBC researcher and The Secret Museum author Molly Oldfield talked about her two years spent seeking out fascinating cultural artifacts the world over, including but not limited to the NYPL’s own collection of things Dickensian. You can hear both Oldfield and Gaiman in the recording below. But perhaps the greatest gift of all came in the form of the latter’s attire for his reading: not only did he go fully Victorian, he even went to the length of replicating the 19th-century literary superstar’s own severe hair part and long goatee. And School Library Journal has pictures. The story really gets started around the 11:00 mark. Gaiman’s reading will be added to our list of Free Audio Books. You can find the text of Dickens’ classic here.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in December 2014.

Related Content:

An Oscar-Winning Animation of Charles Dickens’ Classic Tale, A Christmas Carol (1971)

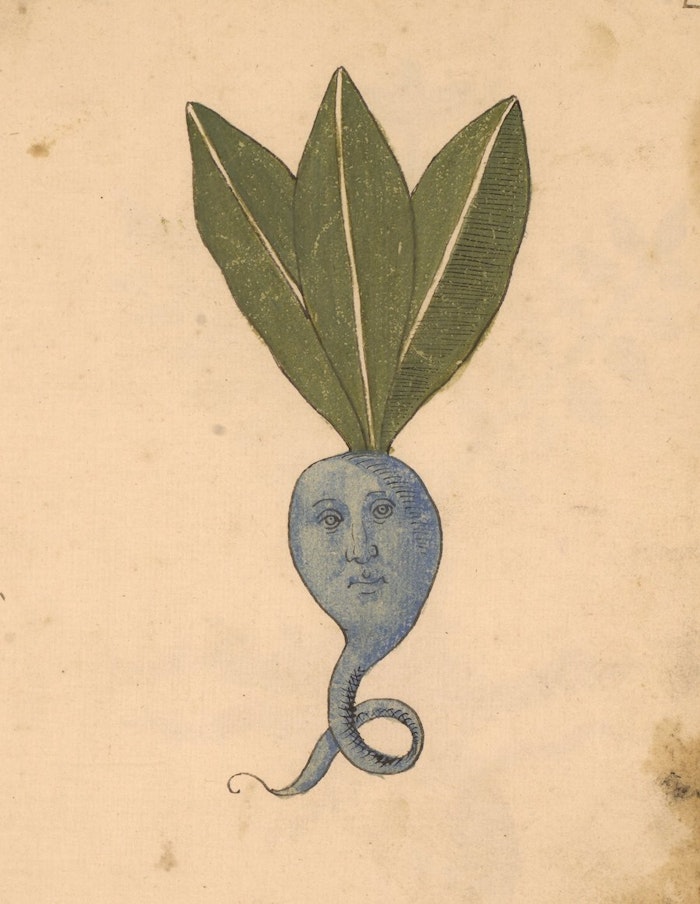

Charles Dickens’ Hand-Edited Copy of His Classic Holiday Tale, A Christmas Carol

Hear Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol Read by His Great-Granddaughter, Monica

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.