English astronomer and physicist James Jeans’ 1931 essay “Why the Sky is Blue” has become a classic of concise expository writing since it was first published in a series of talks. In only four paragraphs and one strikingly detailed, yet simple analogy, Jeans gave millions of students a grasp of celestial blueness in prose that does not substitute nature’s poetry for scientific jargon and diagrams.

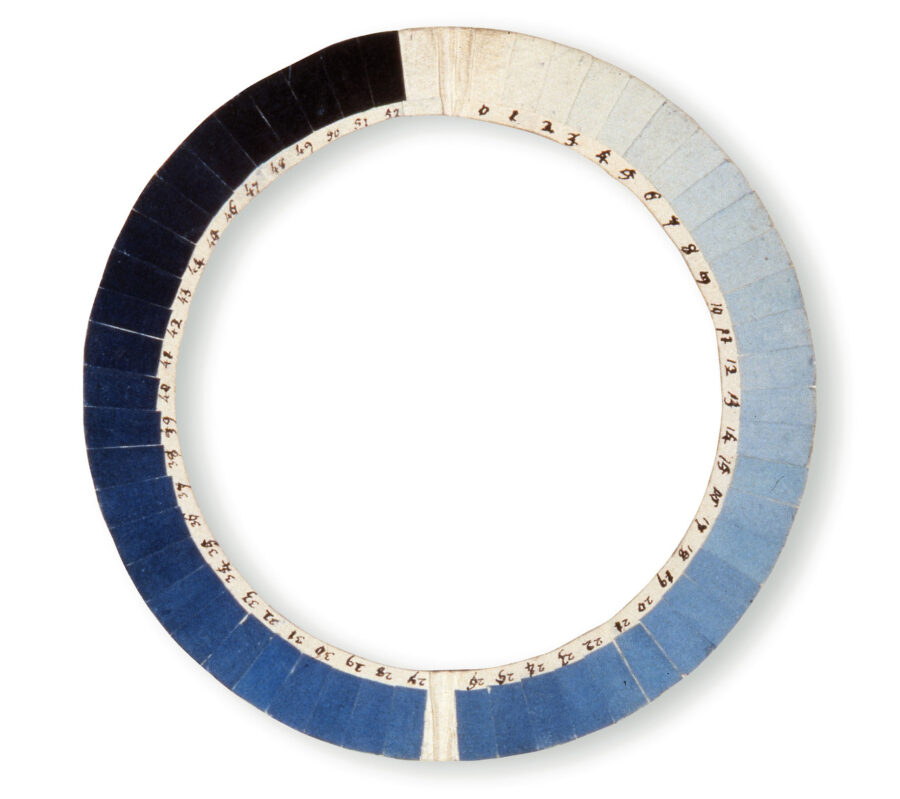

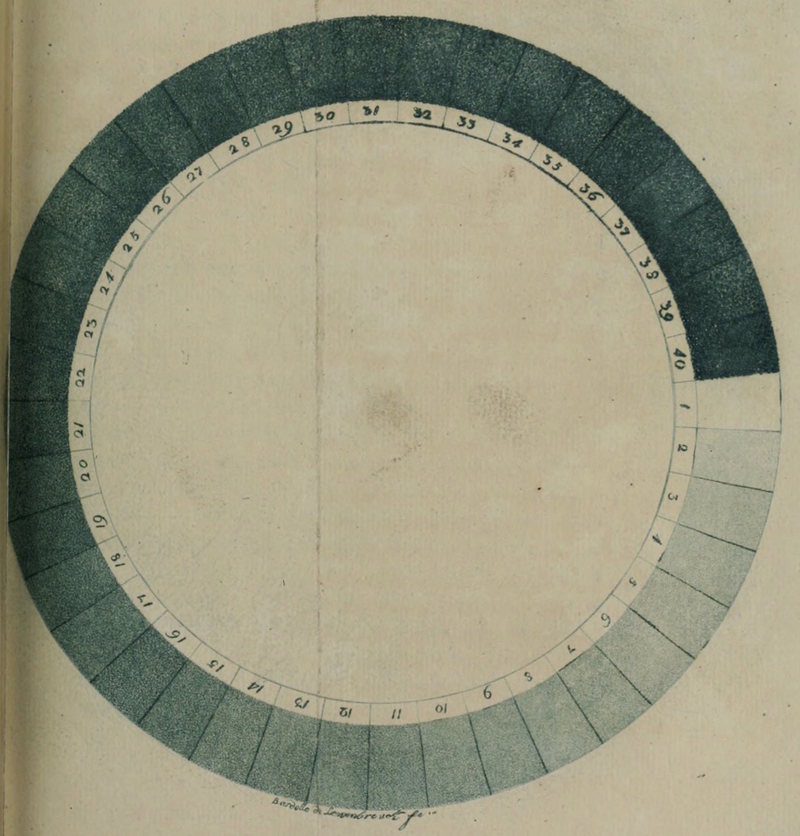

Over a hundred years earlier, another scientist created a similarly poetic device; in this case, one which attempted to depict how the sky is blue. Swiss physicist Horace Bénédict de Saussure’s 1789 Cyanometer, “a circle of paper swatches dyed in increasingly deep blues, shading from white to black,” Sarah Laskow writes at Atlas Obscura, “included 52 blues… in its most advanced iteration,” intended to show “how the color of the sky changed with elevation.”

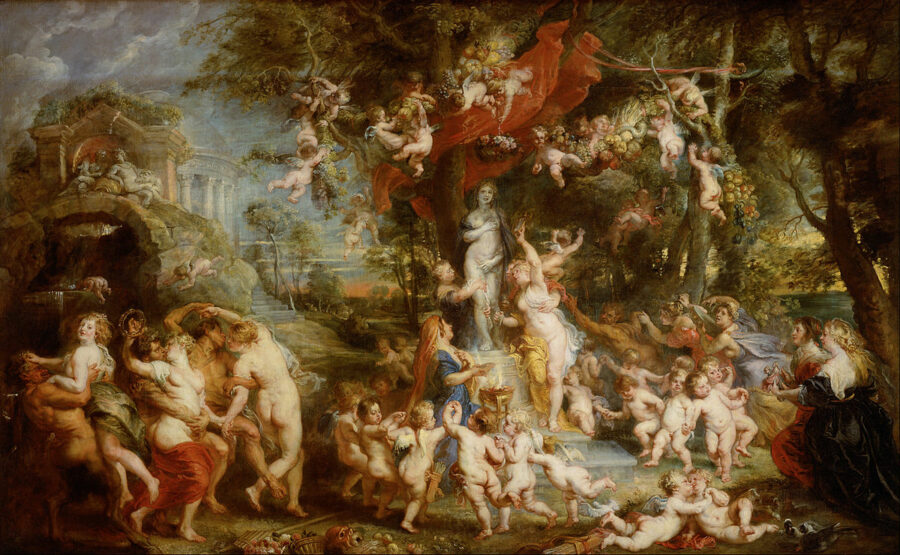

Saussure’s fascination with the blueness of the sky began when he was a young student and traveled to the base of Mont Blanc. Overawed by the summit, he dreamt of climbing it, but instead used his family’s wealth to offer a reward to the first person who could. Twenty-seven years later, Saussure himself would ascend to the top, in 1786, carrying with him “pieces of paper colored different shades of blue, to hold up against the sky and match its color.”

Saussure was taken with a phenomenon reported by mountaineers: as one climbs higher, the sky turns a deeper shade of blue. He began to formulate a hypothesis, the Royal Society of Chemistry Explains:

Armed with his tools and a small chemistry set, he trekked round the valleys and beyond. As his trips carried him ever higher, he puzzled about the colour of the sky. Local legend had it that if one climbed high enough it turned black and one would see, or even fall into, the void — such terrors kept ordinary men away from the peaks. But to Saussure, the blue colour was an optical effect. And because on some days the blue of the sky faded imperceptibly into the white of the clouds, Saussure concluded that the colour must indicate its moisture content.

At the top of Mont Blanc, the physicist measured what he deemed “a blue of the 39th degree.” The number meant little to anyone but him. “Upon its invention, the cyanometer rather quickly fell into disuse,” as Maria Gonzalez de Leon points out. “After all, very little scientific information was given.”

The tool did, however, accompany the famed geographer Alexander von Humboldt across the Atlantic, “to the Caribbean, the Canary Islands, and South America,” writes Laskow, where Humboldt “set a new record, at the 46th degree of blue, for the darkest sky ever measured” on the summit of the Andean mountain Chimborazo. This would be one of the only notable uses of the poetic device. “When the true cause of the sky’s blueness, the scattering of light, was discovered decades later, in the 1860s, Saussure’s circle of blue had already fallen into obscurity.”

via MessyNessy/Colossal

Related Content:

A 900-Page Pre-Pantone Guide to Color from 1692: A Complete Digital Scan

The Vibrant Color Wheels Designed by Goethe, Newton & Other Theorists of Color (1665–1810)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness