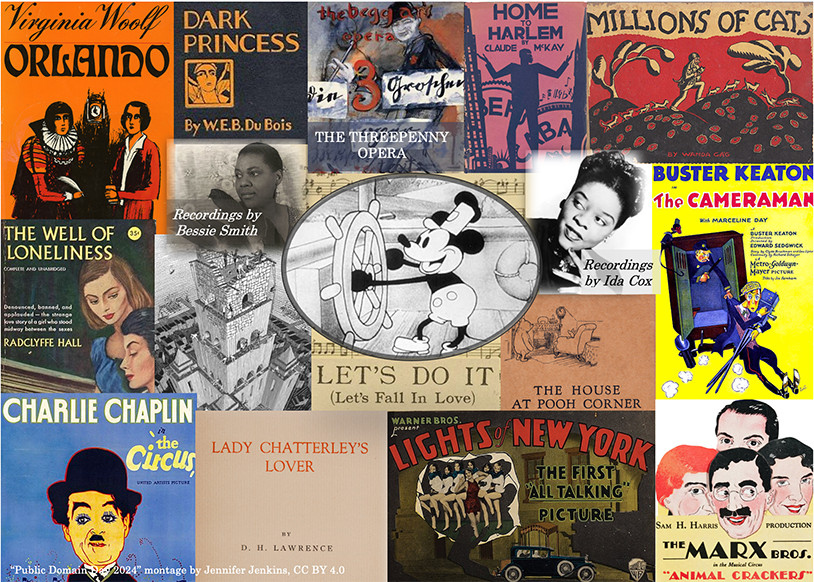

More than thirty years after it was first privately published in 1928, Lady Chatterley’s Lover became the subject of the most famous obscenity trial in English history. Though the ultimate decision of R v Penguin Books Ltd in favor of the publisher opened a cultural floodgate in that country, the novel was also subject to bans elsewhere, including the United States and Japan. Nearly a century after D. H. Lawrence wrote Lady Chatterley’s Lover — and a world apart as regards attitudes about public morality — it can be somewhat difficult to understand what all the fuss was about. But now that the book has entered the public domain in the United States, it could potentially be made artistically and socially dangerous again.

The same could be said of a number of other notable works of literature, from Virginia Woolf’s sex-switching satire Orlando to Bertolt Brecht’s piece of revolutionary theater Die Dreigroschenoper (known in translation as The Threepenny Opera) to a cultural phenomenon-spawning story like J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan; or the Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up.

These and others are named on this year’s Public Domain Day post by Jennifer Jenkins, director of the Duke Center for the Study of the Public Domain. If not for multiple extensions of copyright law, she notes, all of them would have originally gone public domain in 1984, and we would now have almost four decades’ worth of additional creations reinterpreting, re-imagining, and re-using them. Still, “better late than never!”

At this point in history, the artifacts freed for anyone’s use aren’t just written works, but also films, musical compositions, and even actual sound recordings. These include classic Disney cartoons Steamboat Willie and Plane Crazy, which introduced the world to a certain Mickey Mouse; live-action movies from major filmmakers, like Charlie Chaplin’s The Circus and Carl Theodor Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc; and such songs with broad cultural footprints as “Yes! We Have No Bananas,” “When You’re Smiling,” and “Mack the Knife” — or rather “Die Moritat von Mackie Messer,” in the original German from Die Dreigroschenoper. Alas, those of us who want to do our own thing with Bobby Darin’s version will have to wait until February of 2067.

Related Content:

An Early Version of Mickey Mouse Enters the Public Domain on January 1, 2024

The Disney Cartoon That Introduced Mickey Mouse & Animation with Sound (1928)

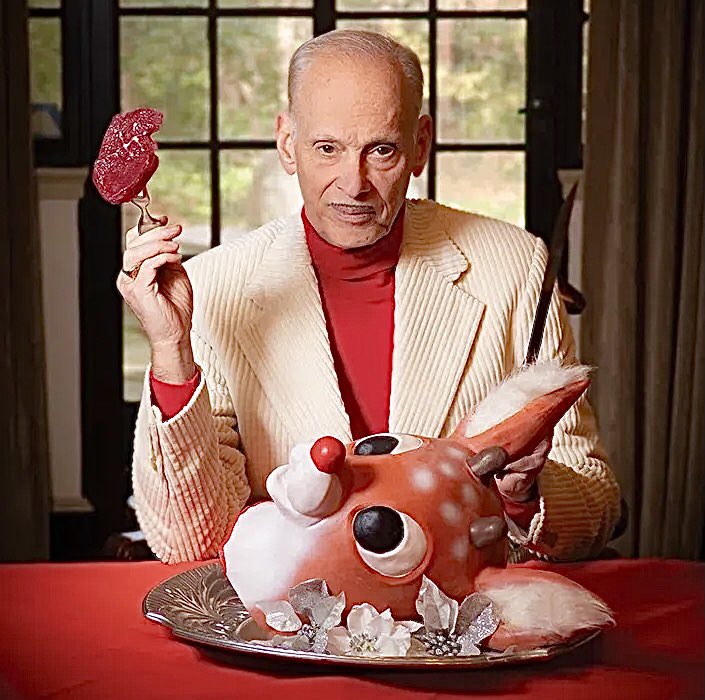

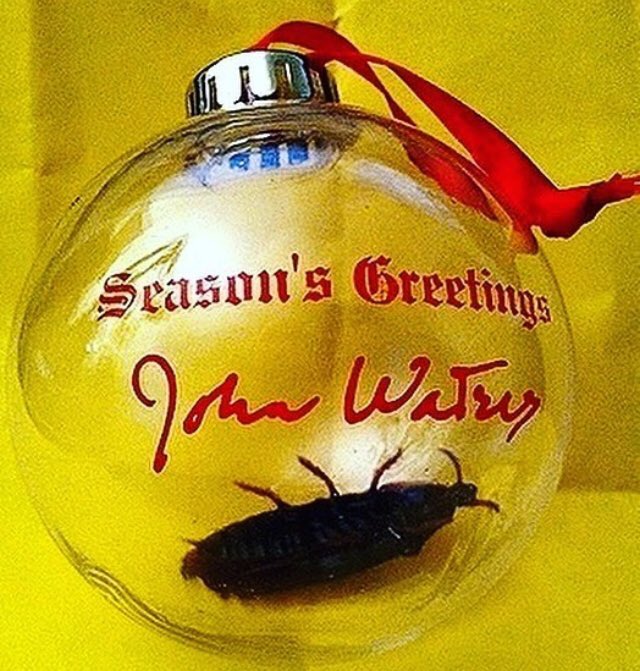

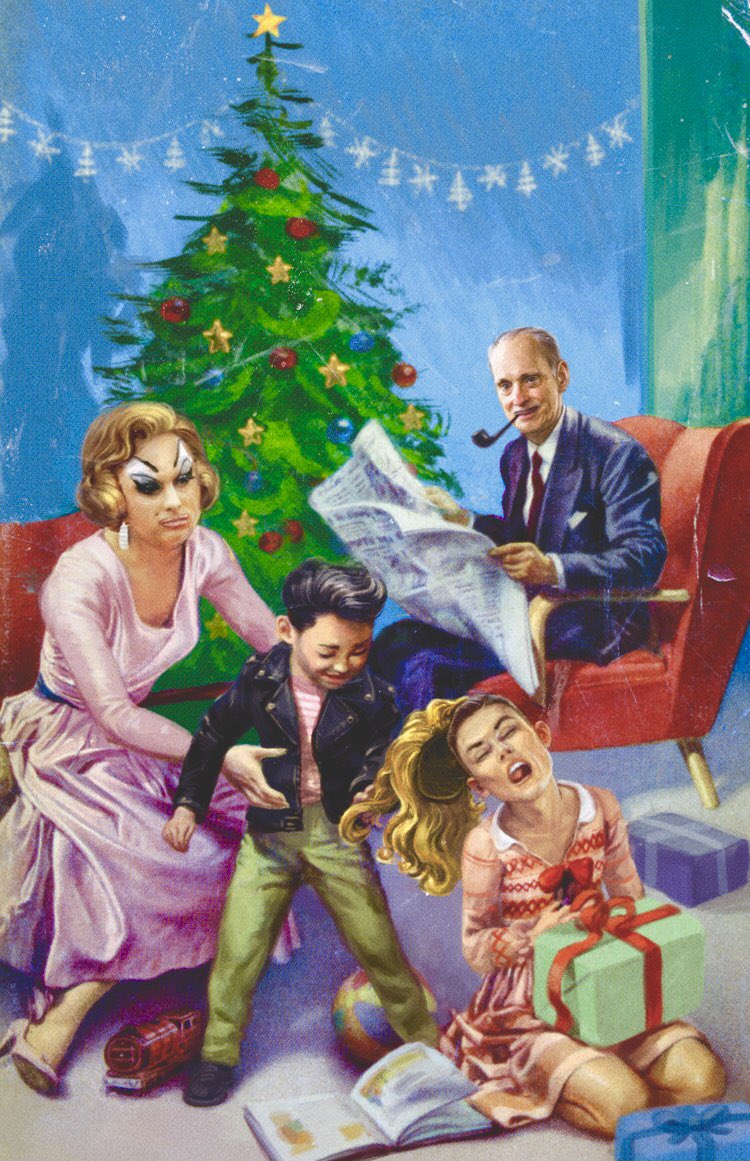

John Waters Reads Steamy Scene from Lady Chatterley’s Lover for Banned Books Week (NSFW)

The British Library Digitizes Its Collection of Obscene Books (1658–1940)

Bertolt Brecht Sings ‘Mack the Knife’ From The Threepenny Opera (1929)

Watch Online: The Passion of Joan of Arc by Carl Theodor Dreyer (1928)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.