My Penguin Classics copy of Mark Twain’s Life on the Mississippi sits alone atop an overfull shelf. There is a bookmark on page 204, exactly halfway through, torn from an in-flight duty-free catalog—whiskey and fancy pens. It tells me “hey, you forgot to finish this, you [various obscenities].” And I shrug. What can I say? I went to grad school, where I learned to read ten books at once and never finish one. Good thing Mark Twain didn’t write that way, or we might not have Life on the Mississippi.

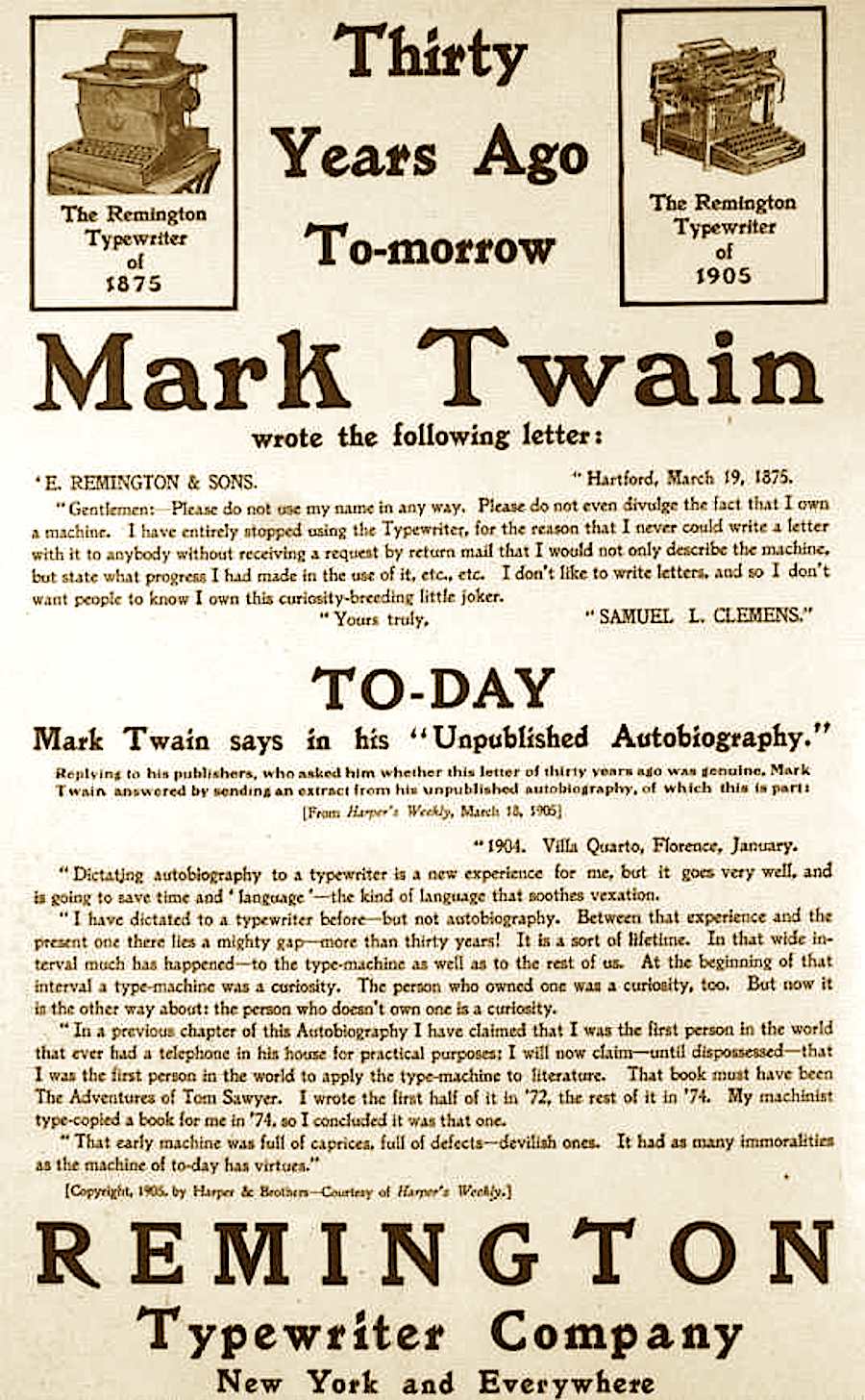

Twain was a diligent and conscientious writer with a memory like a bear trap, or at least that’s what he wanted us to think. But somewhere in his reminiscence he may have been confused. Twain wrote in his 1904 autobiography that his first novel written on a typewriter—the first typewritten novel at all—was Tom Sawyer.

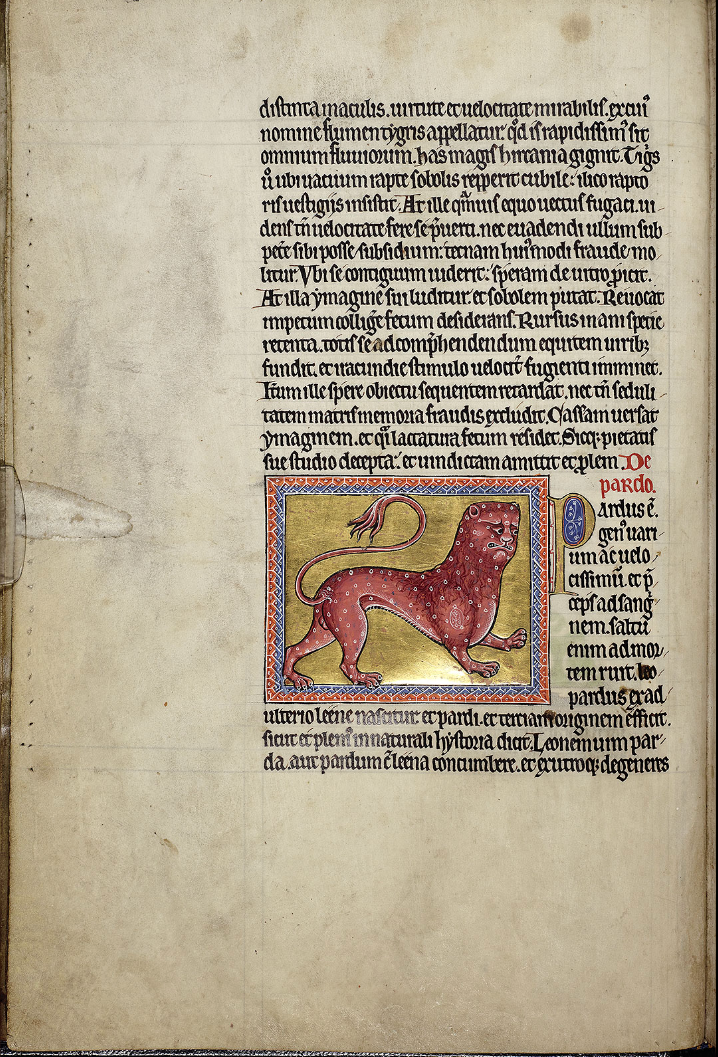

Was this so? Twain purchased his first typewriter (which probably looked like the Sholes and Glidden seen here) in 1874 for $125. In 1875, he writes in a letter to the Remington company that he is no longer using his typewriter; it corrupts his morals because it makes him want to swear. He gives the infernal machine away, twice. It returns to him each time.

The year after Twain’s moral trouble with his Remington, Tom Sawyer is published from handwritten manuscript, not typed. Then, seven years later, Life on the Mississippi (1883) comes to the publisher in typescript. Twain did not type it himself—he had presumably renounced the act—but he dictated the memoir to a typist from a handwritten draft. Now, I can hear you quibbling… Life on the Mississippi isn’t a novel at all! Well, okay, fair enough. Let’s just say it’s the first typewritten book and call it a day, eh? Go read this excellent New Yorker piece on the early life of the typewriter and leave me alone. I’ve got a book to finish.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2013.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Mark Twain Makes a List of 60 American Comfort Foods He Missed While Traveling Abroad (1880)

The Only Footage of Mark Twain: The Original & Digitally Restored Films Shot by Thomas Edison

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC.