Vincent Van Gogh’s The Starry Night is one of the most popular and easily recognized paintings on earth. If you haven’t seen it person, you’ve probably seen it reproduced on a postcard, a tote bag, or a t‑shirt.

Musician Sheldon Clarke was a Starry Night virgin when he started working as a security officer at the Museum of Modern Art:

I knew nothing about Vincent or Starry Night before I started working here. And I remember the first time I stood at that painting…first of all, I was so amazed at the reaction of the public. There was always a group of people just fighting to look at it or take pictures or take selfies and I was just curious to know like, who is this painter and why is everyone so excited to see this piece?

Now, Clarke is sufficiently well versed to hold forth on both the nature of the artwork and circumstances in which the artist created it. He is, with Senior Paintings Conservator Anny Aviram, Associate Curator Cara Manes, and Robert Kastler, director of Imaging and Visual Resources, one of four MoMA staffers to give some context, while trying their hands at the new Starry Night LEGO set.

A collaboration between MoMA and LEGO, the set reinterprets Van Gogh’s thick impasto brushwork in 2316 tiny plastic bricks, including a mini figure of the artist, equipped with paintbrush, palette, easel, and an adjustable arm for positioning him at sufficient distance to gain perspective on his world famous work.

The set is the winning entry in a LEGO Ideas competition. Designer Truman Cheng, a 25-year-old LEGO fan and PhD candidate focusing on medical robotics and magnetic controlled surgical endoscopes. He had long wanted to render The Starry Night in LEGO, bu its execution required a lightbulb moment:

One day, I was just playing with LEGO parts, and I realized that stacking LEGO plates together at random intervals looks a lot like van Gogh’s iconic brush strokes. I couldn’t help but wonder what the full painting would look like with this build style.

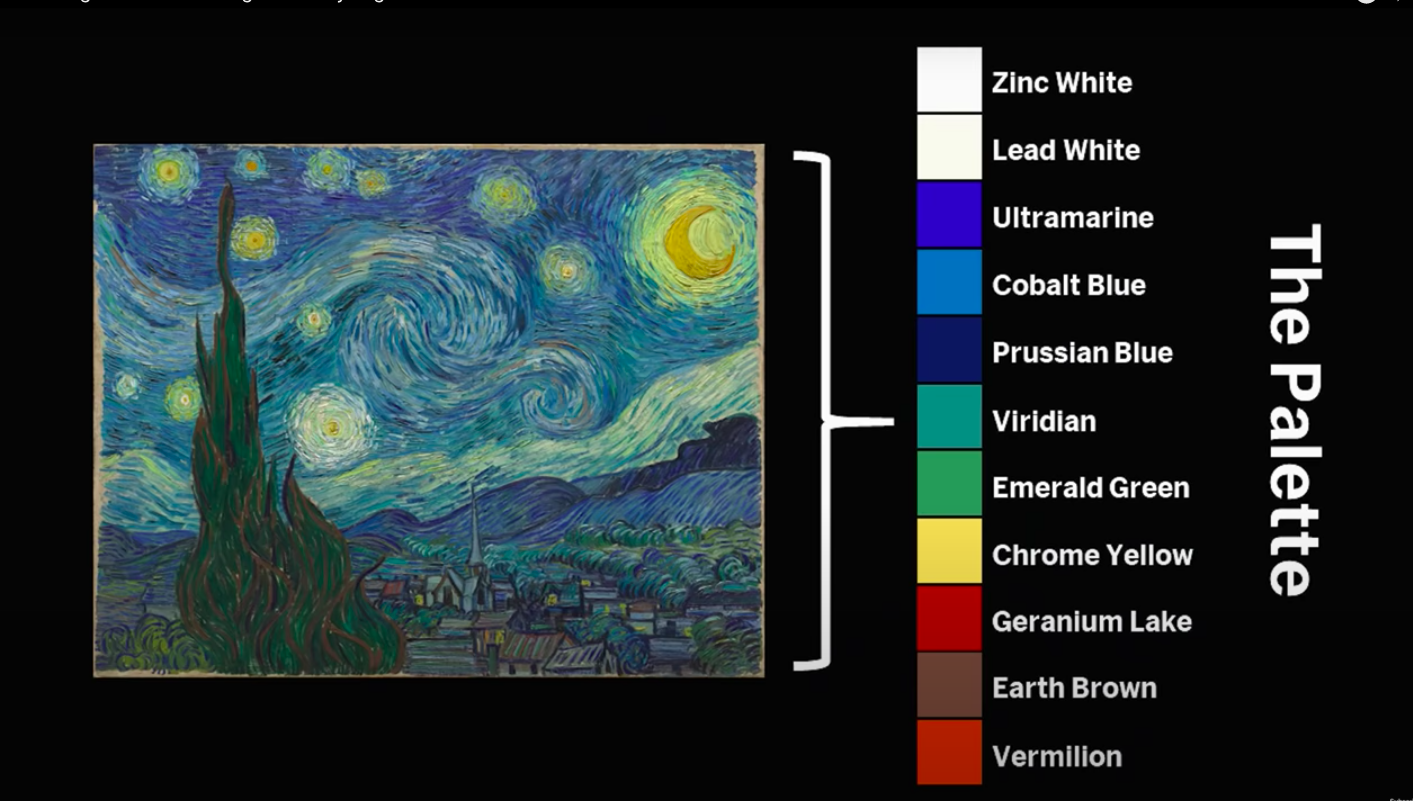

As Aviram and Kastler point out, the set cleaves faithfully to Van Gogh’s limited palette. Some LEGO fans report that building up the blue background layers is the most challenging aspect of assembling the 11”x14.5” kit:

I’m 54 and the colors, being kind of close, were playing games with my eyes. LOL This is my favorite LEGO of all time! In closing, if you haven’t heard the song, Vincent by Don McLean, I suggest you take a listen to this song as you stare at this LEGO masterpiece.

Order LEGO’s Vincent van Gogh - The Starry Night set from Amazon.

Related Content

Vincent Van Gogh’s “The Starry Night”: Why It’s a Great Painting in 15 Minutes

The Unexpected Math Behind Van Gogh’s “Starry Night”

Zoom Into a Super High Resolution Photo of Van Gogh’s “The Starry Night”

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.