As many as a million people crossed the Golden Gate Bridge on foot to celebrate the 50th anniversary of its construction in 1987. More than a few of them would have remembered San Francisco as it was before it had its most iconic structure — and indeed, some would even remember walking across it once before, on its inaugural “Pedestrian Day” in 1937. Barring the possibility of unusually vigorous supercentenarians, that won’t be the case 12 years from now, on the Golden Gate Bridge’s 100th anniversary. But we’ll still be able to appreciate the enormous ambition of its builders, not least its chief design engineer Joseph Strauss, who, along with Charles Alton Ellis, made possible a project long assumed impossible.

The video from Sabin Civil Engineering at the top of the post explains every stage of the Golden Gate Bridge’s design and construction. Building a suspension bridge over the Golden Gate, the deep strait between San Francisco Bay and the Pacific Ocean, posed formidable challenges. The distinctive shape we know from so many photographs emerged in part from the need to anchor the bridge in such a way as to balance out the massive forces that would otherwise bend its towers inward, and the steel-on-steel construction of its suspenders and deck was necessary to prevent catastrophic crack formation.

The deck hangs from 250 pairs of cables, and each of the main cables that run the length of the bridge actually consists of 27,000 steel wires wound together. A system of thermal expansion joints accommodates regular elongation and shrinkage of nearly four feet.

And we haven’t even got into the underwater blasting and terrifying-looking drilling work required to put up the towers in the first place. In any case, the painstaking efforts of the engineers and laborers alike have surely been vindicated by the Golden Gate Bridge’s functionality and popularity over the past 88 years. Naturally, it’s had to undergo considerable maintenance and retrofitting in that time, and it would take a true romantic to ignore its limitations entirely. (Take its lack of rail capacity, which was neither technically nor economically feasible to incorporate during the Great Depression.) Still, when 300,000 people jammed themselves onto its deck at once on its 50th anniversary, it may have bent in the middle, but it didn’t break. That was a testament to the civil engineering acumen of Strauss and company — but let’s hope the centenary festivities are better organized.

Related content:

“The Bay Lights,” the World’s Largest LED Light Sculpture, Debuts in San Francisco

The 5 Innovative Bridges That Make New York City, New York City

A Mesmerizing Trip Across the Brooklyn Bridge: Watch Footage from 1899

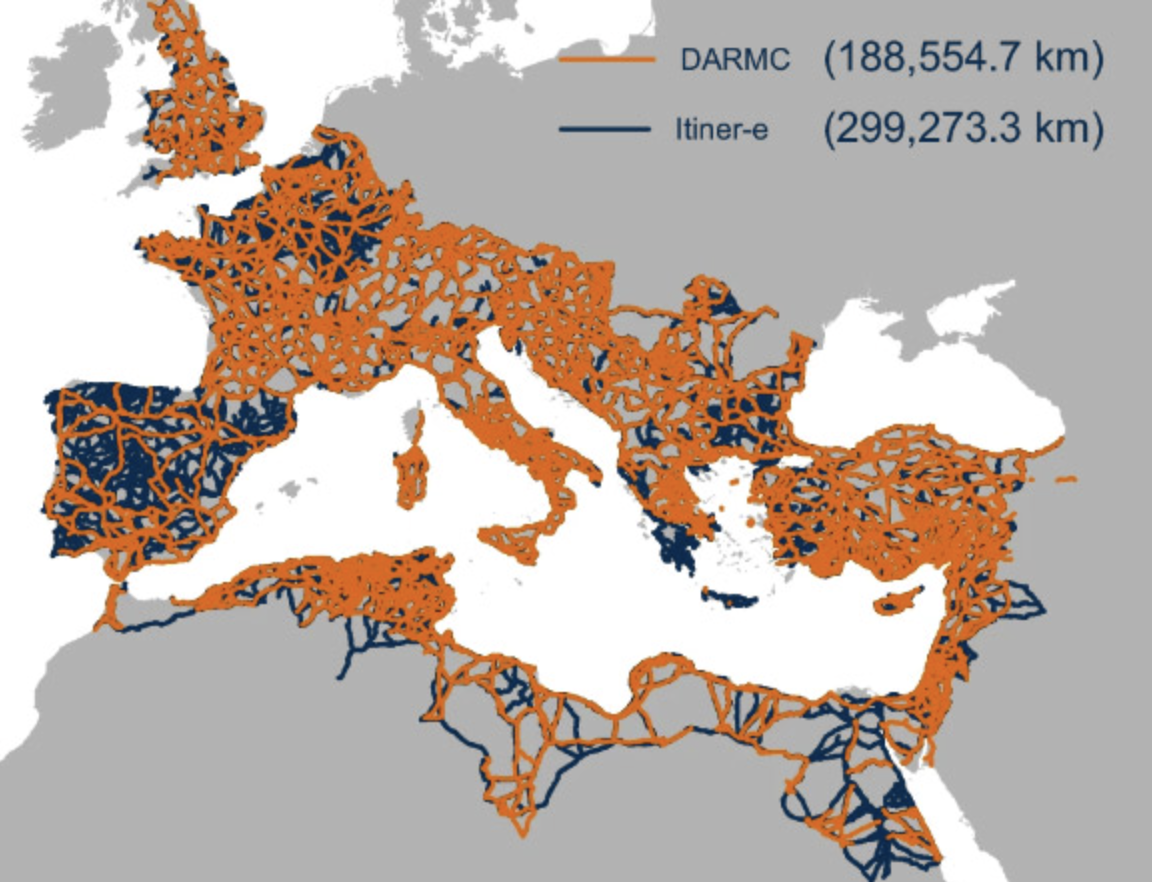

Built to Last: How Ancient Roman Bridges Can Still Withstand the Weight of Modern Cars & Trucks

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.