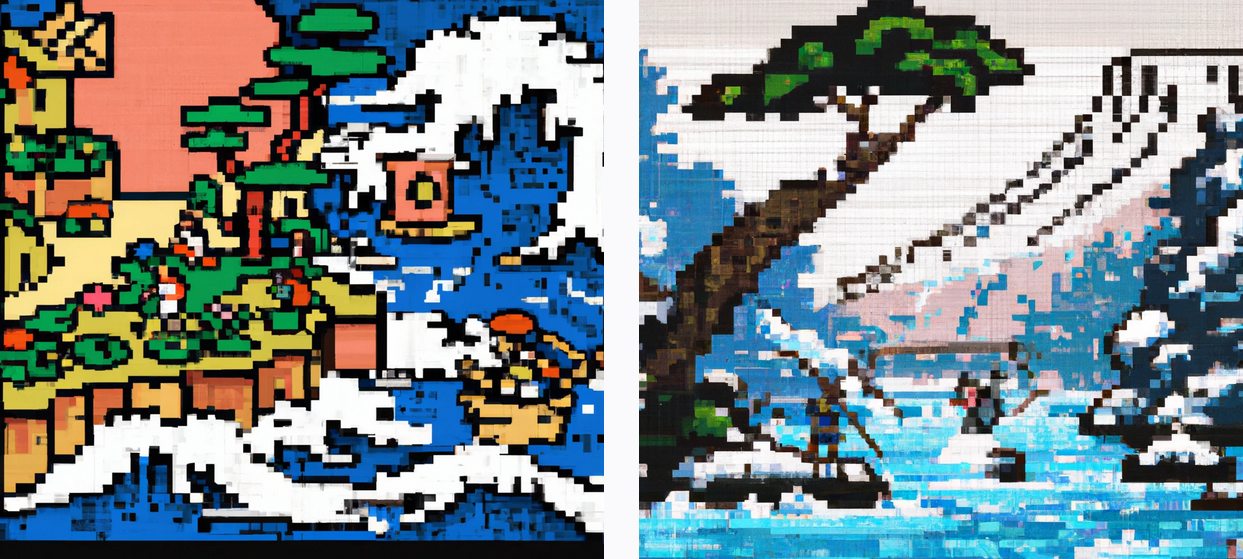

“By the time of his death”—almost two years before, in fact—“Van Gogh’s work had begun to attract critical attention,” writes the Metropolitan Museum of Art, who point out that Van Gogh’s works shown “at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris between 1888 and 1890 and with Les XX in Brussels in 1890… were regarded by many artists as ‘the most remarkable’” in both exhibits. Critics wrote glowing appreciations, and Van Gogh seemed poised to achieve the recognition everyone knows he deserved in his lifetime. Still, Van Gogh himself was not present at these exhibitions. He was first in Arles, where he settled in near-seclusion (save for Gauguin), after cutting off part of his ear. Then, in 1889, he arrived at the asylum near Saint-Rémy, where he furiously painted 150 canvases, then shot himself in the chest, thinking his life’s work a failure, despite the public recognition and praise his brother Theo poignantly tried to communicate to him in his final letters.

Now imagine that Van Gogh had actually been able to experience the acclaim bestowed on him near the end—or the acclaim bestowed on him hundreds of times over in the more than 100 years since his death. Such is the premise of the clip above from Doctor Who, Series 5, Episode 10, in which Van Gogh—who struggled to sell any of his work through most of his lifetime—finds himself at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris in 2010, courtesy of the TARDIS. Granted, the scene milks the inherent pathos with some maudlin musical cues, but watching actor Tony Curran react as Van Gogh, seeing the gallery’s collections of his work and the wall-to-wall admirers, is “unexpectedly touching,” as Kottke writes. To drive the emotional point even further home, the Doctor calls over a docent played by Bill Nighy, who explains why “Van Gogh is the finest painter of them all.” Laying it on thick? Fair enough. But try not getting a little choked up at the end, I dare you.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2016.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Martin Scorsese Plays Vincent Van Gogh in a Short, Surreal Film by Akira Kurosawa

Download Free Doctor Who Backgrounds for Virtual Meetings (Plus Many Other BBC TV Shows)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness