For all its talk of liberty, the US government has practiced dehumanizing authoritarianism and mass murder since its founding. And since the rise of fascism in the early 20th century, it has never been self-evident that it cannot happen here. On the contrary — wrote Yale historian Timothy Snyder before and throughout the Trump presidency — it happened here first, though many would like us to forget. The histories of southern slavocracy and manifest destiny directly informed Hitler’s plans for the German colonization of Europe as much as did Europe’s 20th-century colonization of Africa and Asia.

Snyder is not a scholar of American history, though he has much to say about his country’s present. His work has focused on WWII’s totalitarian regimes and his popular books draw from a “deep knowledge of twentieth-century European history,” write Françoise Mouly and Genevieve Bormes at The New Yorker.

These books include bestsellers like Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin and the controversial Black Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning, a book whose arguments, he said, “are clearly not my effort to win a popularity contest.”

Indeed, the problem with rigid conformity to populist ideas became the subject of Snyder’s 2017 bestseller, On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century, “a slim volume,” Mouly and Bormes note, “which interspersed maxims such as ‘Be kind to our language’ and ‘Defend institutions’ with biographical and historical sketches.” (We posted an abridged version of Snyder’s 20 lessons that year.) On Tyranny became an “instant best-seller… for those who were looking for ways to combat the insidious creep of authoritarianism at home.”

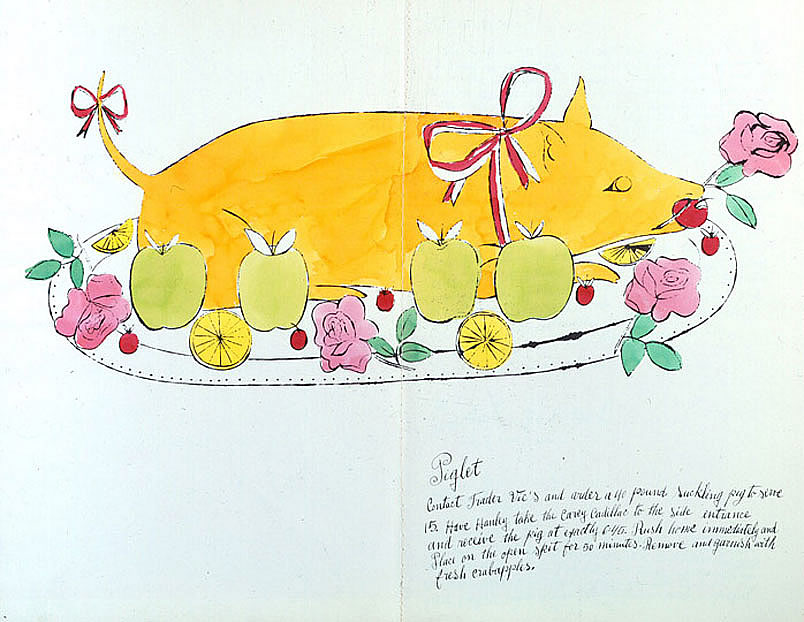

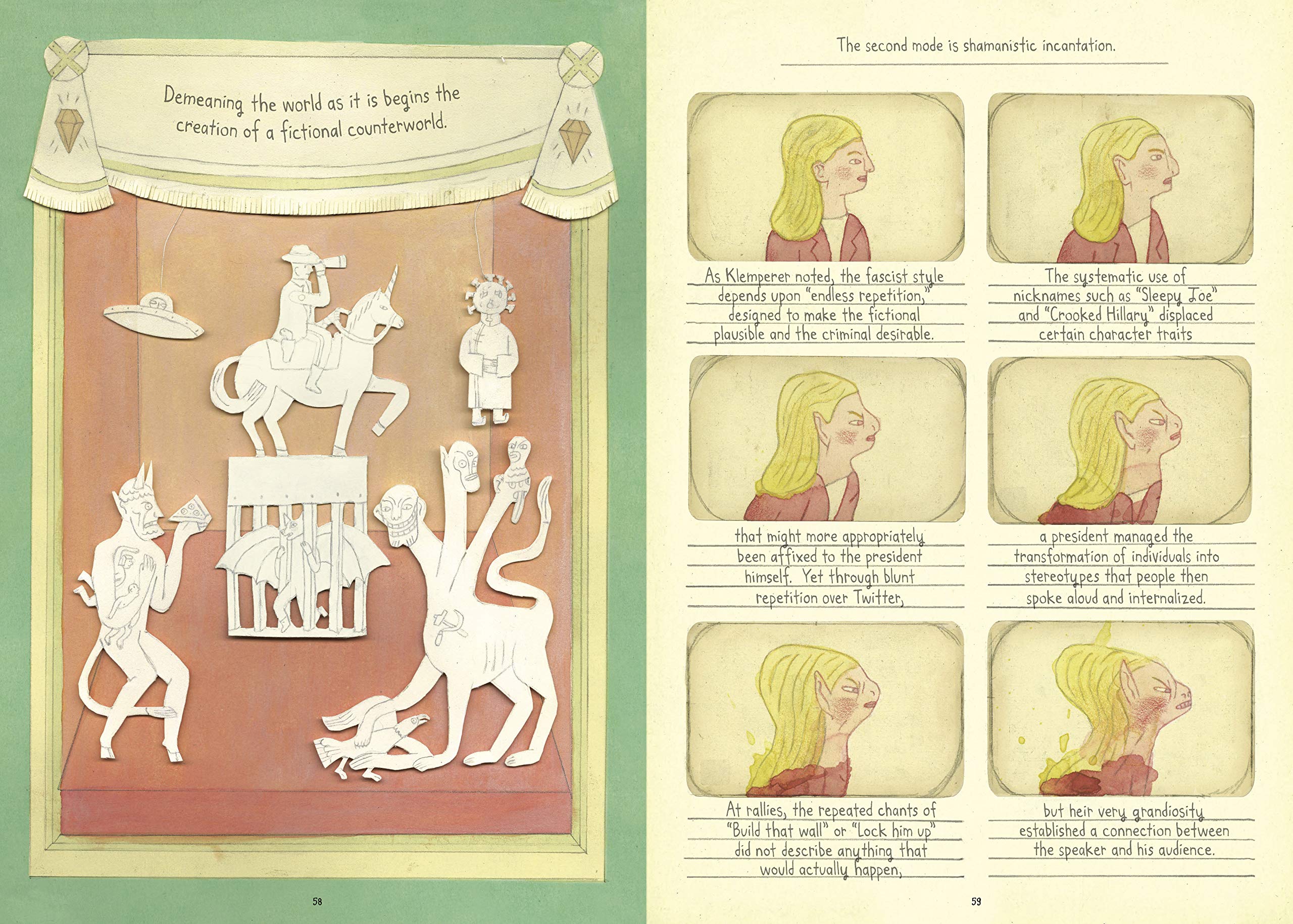

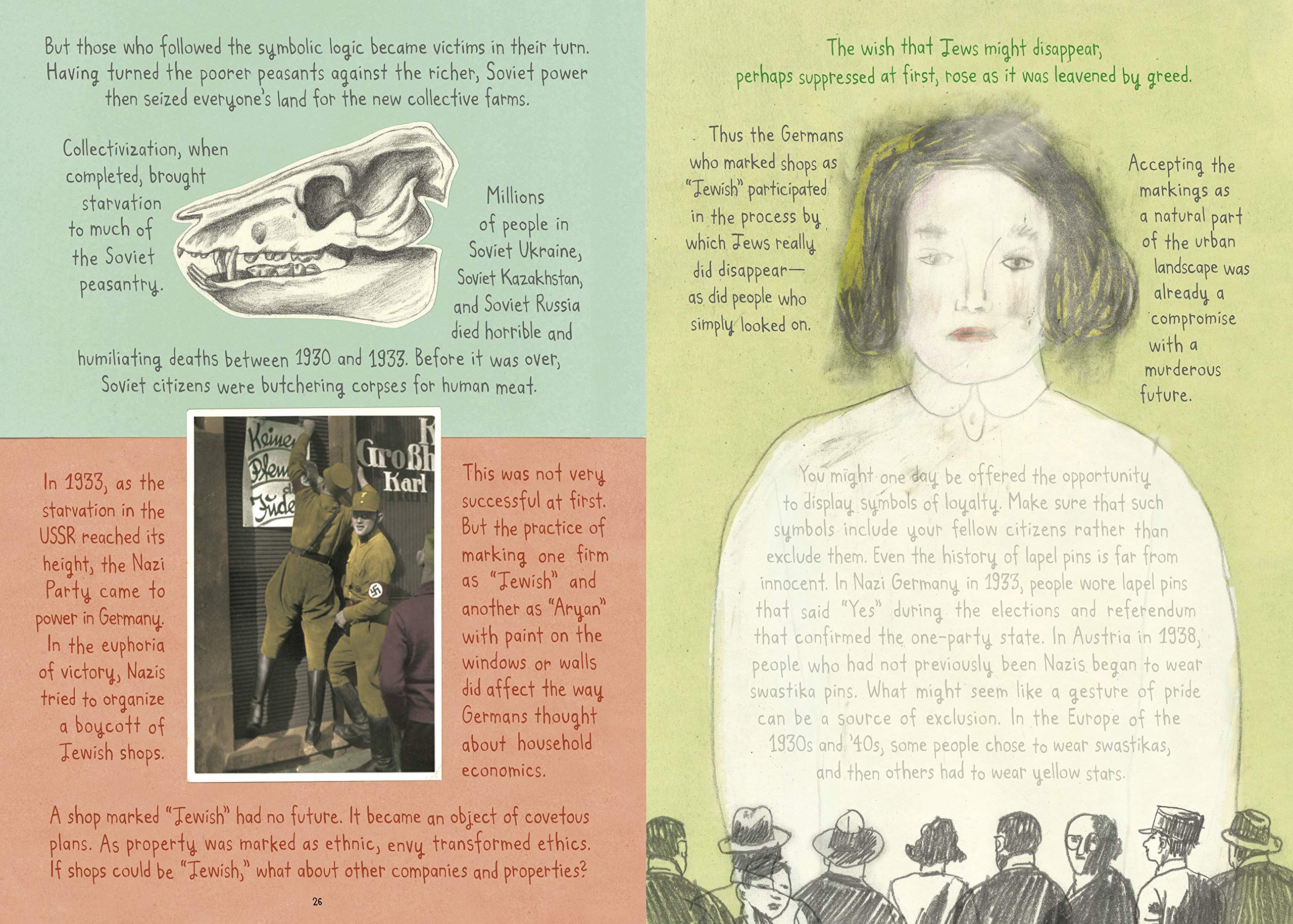

If you’ve paid any attention to the news lately, maybe you’ve noticed that the threat has not receded. Ideas about how to combat anti-democratic movements remain relevant as ever. It’s also important to remember that Snyder’s book dates from a particular moment in time and draws on a particular historical perspective. Contextual details that can get lost in writing come to the fore in images — clothing, cars, the use of color or black and white: these all key us in to the historicity of his observations.

“We don’t exist in a vacuum,” says artist Nora Krug, the designer and illustrator of a new, graphic edition of On Tyranny just released this month. “I use a variety of visual styles and techniques to emphasize the fragmentary nature of memory and the emotive effects of historical events.” Krug worked from artifacts she found at flea markets and antique stores, “depositories of our collective consciousness,” as she writes in an introductory note to the new edition.

Krug’s choice of a variety of mediums and creative approaches “allows me to admit,” she says, “that we can only exist in relationship to the past, that everything we think and feel is thought and felt in reference to it, that our future is deeply rooted in our history, and that we will always be active contributors to shaping how the past is viewed and what our future will look like.”

It’s an approach also favored by Snyder, who does not shy away, like many historians, from explicitly making connections between past, present, and possible future events. “It’s easy for historians to say, ‘It’s not our job to write the future,’” he told The New York Times in 2015. “Yes, right. But then whose job is it?” See many more images from the illustrated On Tyranny at The New Yorker and purchase a copy of the book here.

Via Kottke

Related Content:

Umberto Eco Makes a List of the 14 Common Features of Fascism

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness