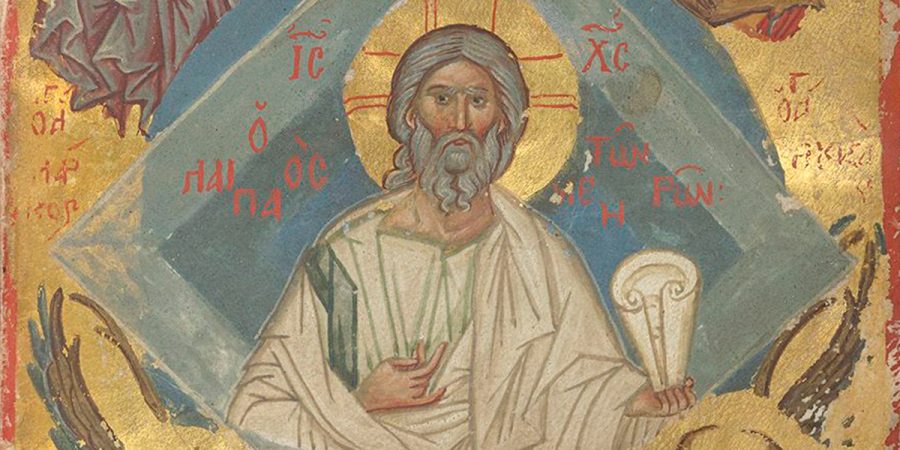

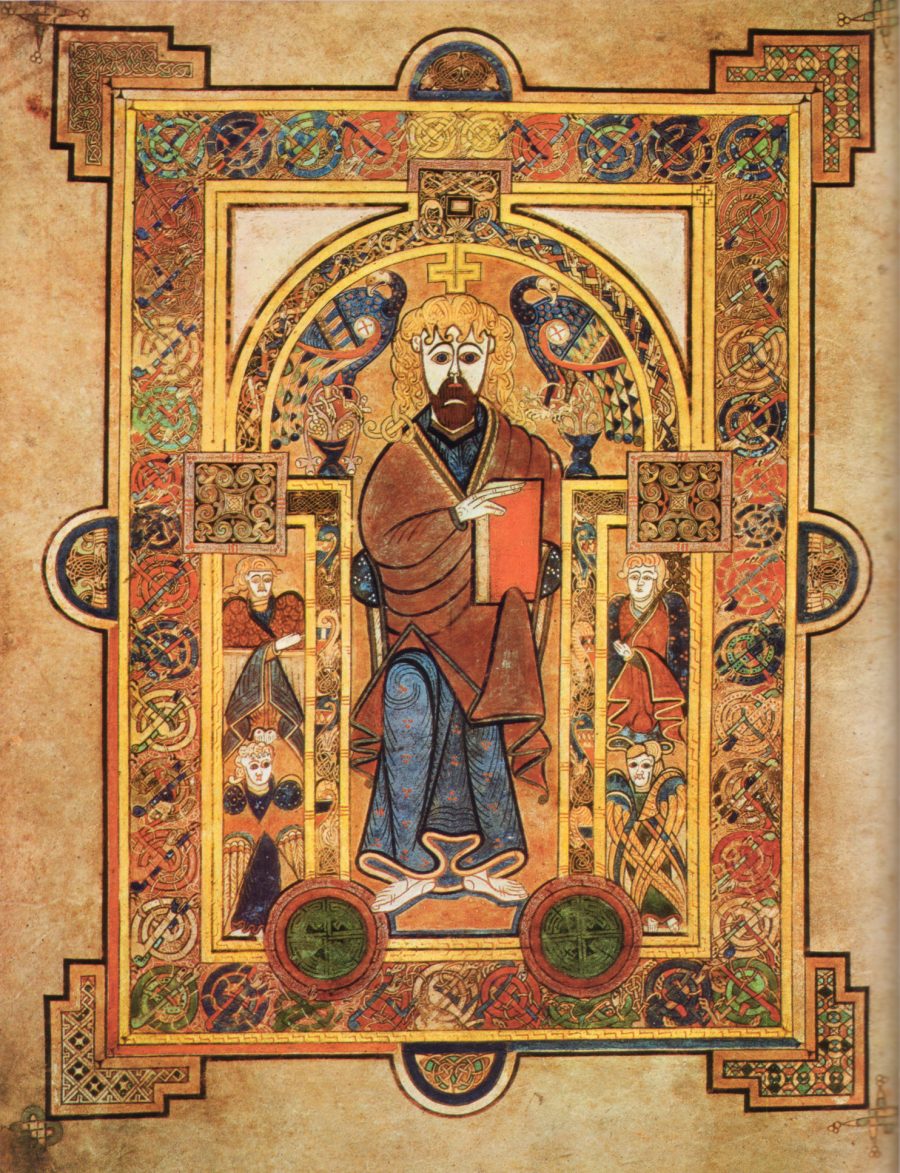

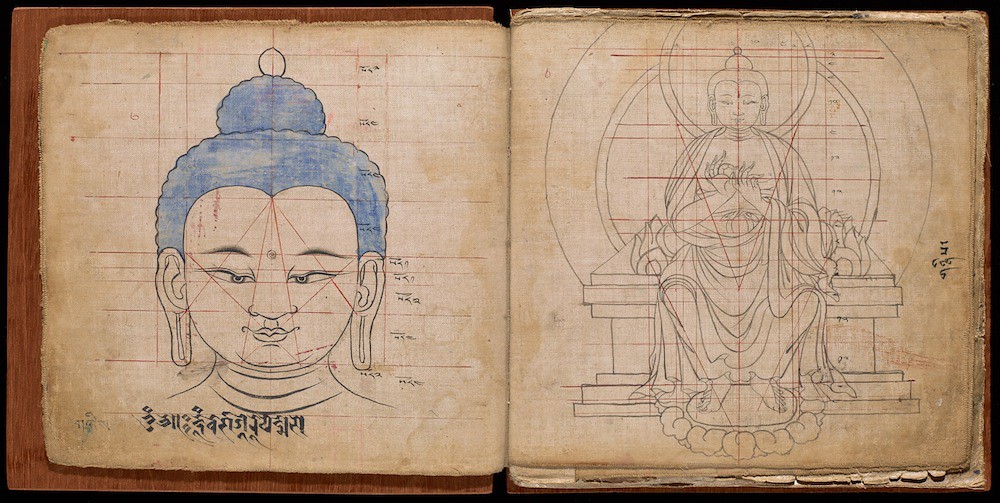

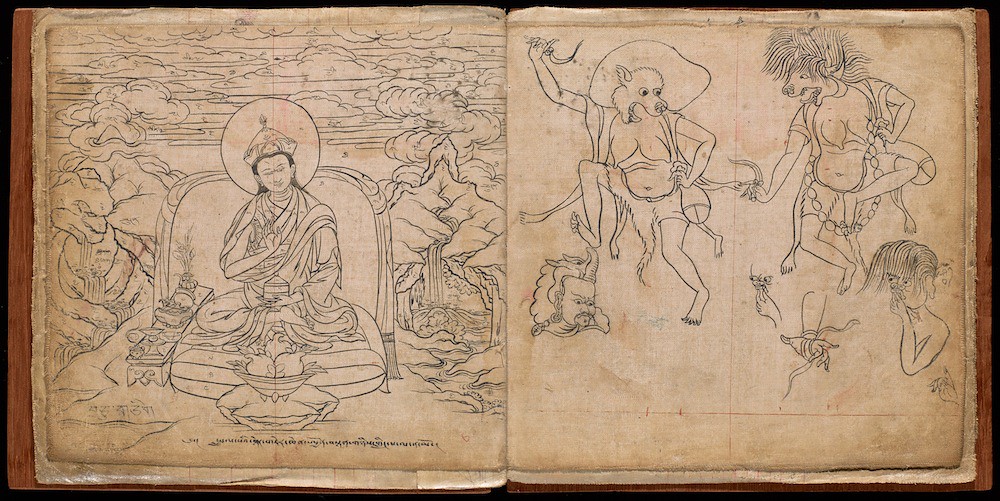

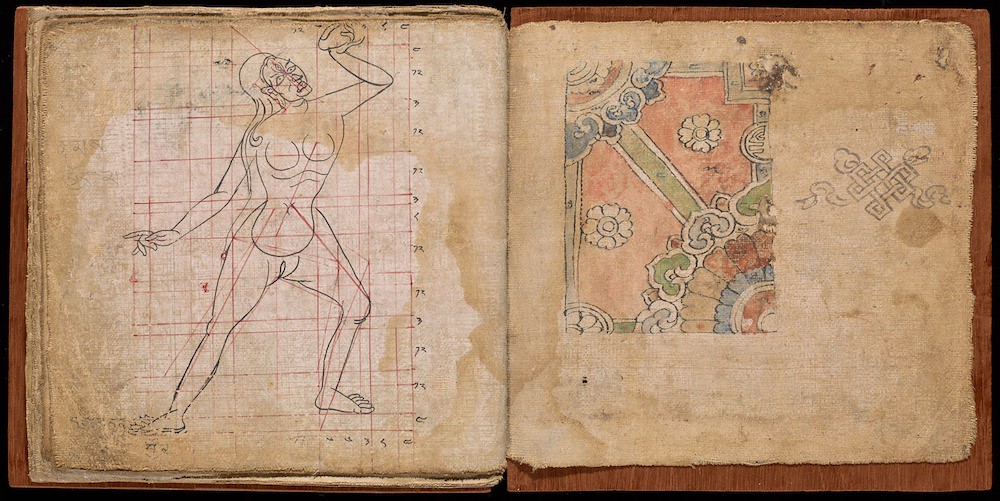

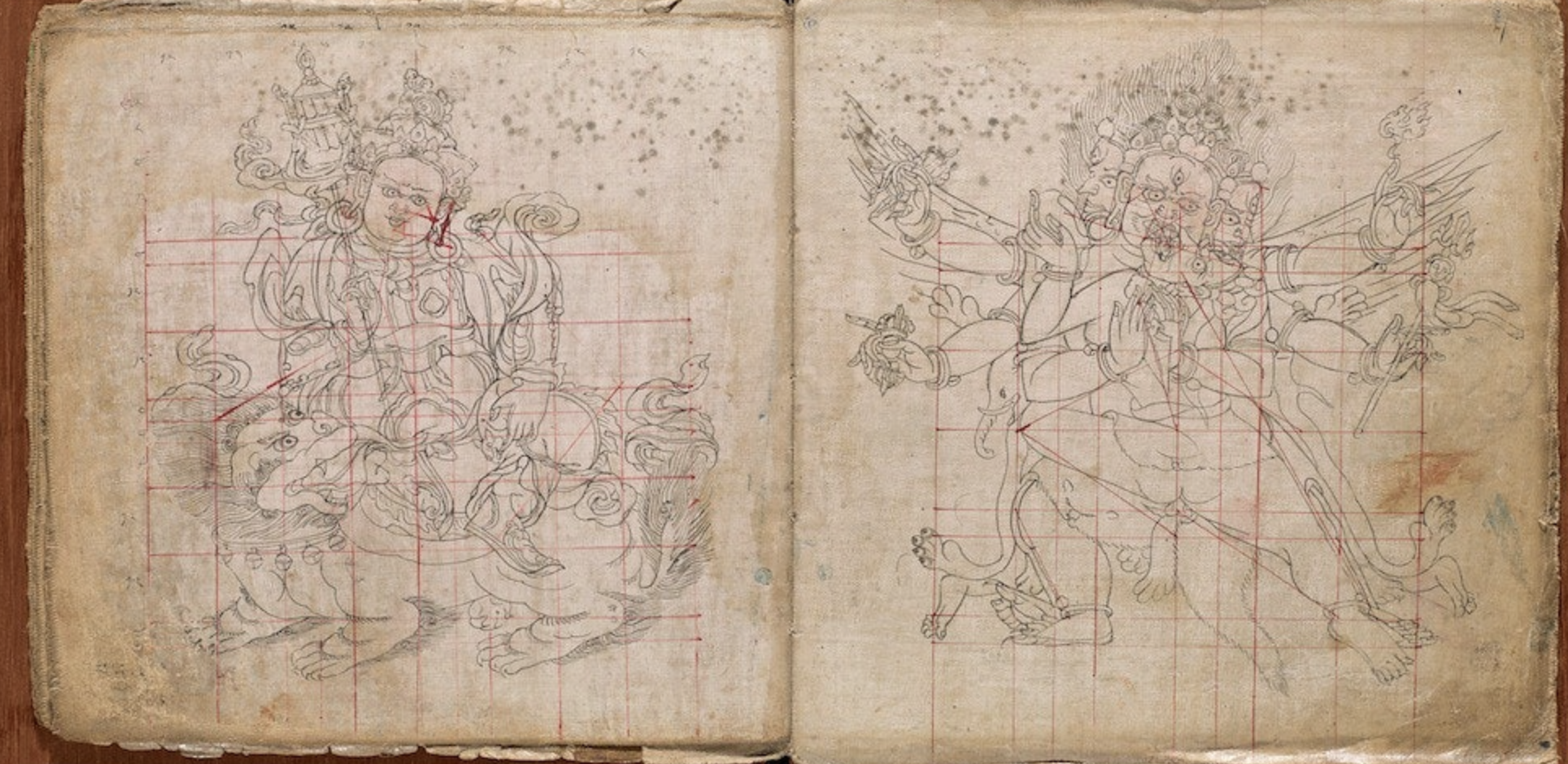

Some religions prohibit the depiction of their sacred personages. Tibetan Buddhism isn’t quite so strict, but it does ask that, if you’re going to depict the Buddha, you do it right. Hence aids like the Tibetan Book of Proportions, which provides “36 ink drawings showing precise iconometric guidelines for depicting the Buddha and Bodhisattva figures.” That description comes from the Public Domain Review, where you can behold many of those pages. Printed in the 18th century, “the book is likely to have been produced in Nepal for use in Tibet.” Now you’ll find it at the Getty Center in Los Angeles, which had made the book free to read at its digital collections.

To read it properly, of course, you’ll have to know your Newari script and Tibetan numerals. But even without them, anyone can appreciate the elegance of not just the book’s recommended proportions — all presented on a standardized and notated grid — but of the book itself as well.

By the time this volume appeared, the printing used for texts related to Tibetan Buddhism had long since shown itself to be a cut above: take the 15th-century collection of recitation texts, previously featured here on Open Culture, printed forty years before the Gutenberg Bible. Only a printing culture that had mastered this level of detail could produce a book like the Tibetan Book of Proportions, visual exactitude being its entire raison d’être.

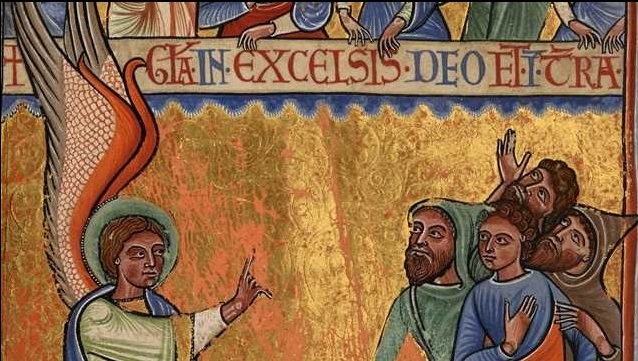

“The concept of the ‘ideal image’ of the Buddha emerged during the Golden Age of Gupta rule, from the 4th to 6th century,” says the Public Domain Review. During that Indian empire’s dominance, the importance of such depictions extended even beyond proportions to details like “number of teeth, color of eyes, direction of hairs.” Surely when it comes to showing one who has attained nirvana — or a bodhisattva, the designation for those on their way to nirvana — one can’t be too careful. Nevertheless, artworks in the form of the Buddha (of which the Victoria and Albert Museum offer a small sampling on their web site) have taken different shapes in different times and places. No matter how well-defined the ideal, the earthly realm always finds a way to introduce some variety.

Related Content:

Breathtakingly Detailed Tibetan Book Printed 40 Years Before the Gutenberg Bible

The World’s Largest Collection of Tibetan Buddhist Literature Now Online

Leonard Cohen Narrates Film on The Tibetan Book of the Dead, Featuring the Dalai Lama (1994)

Tibetan Musical Notation Is Beautiful

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.