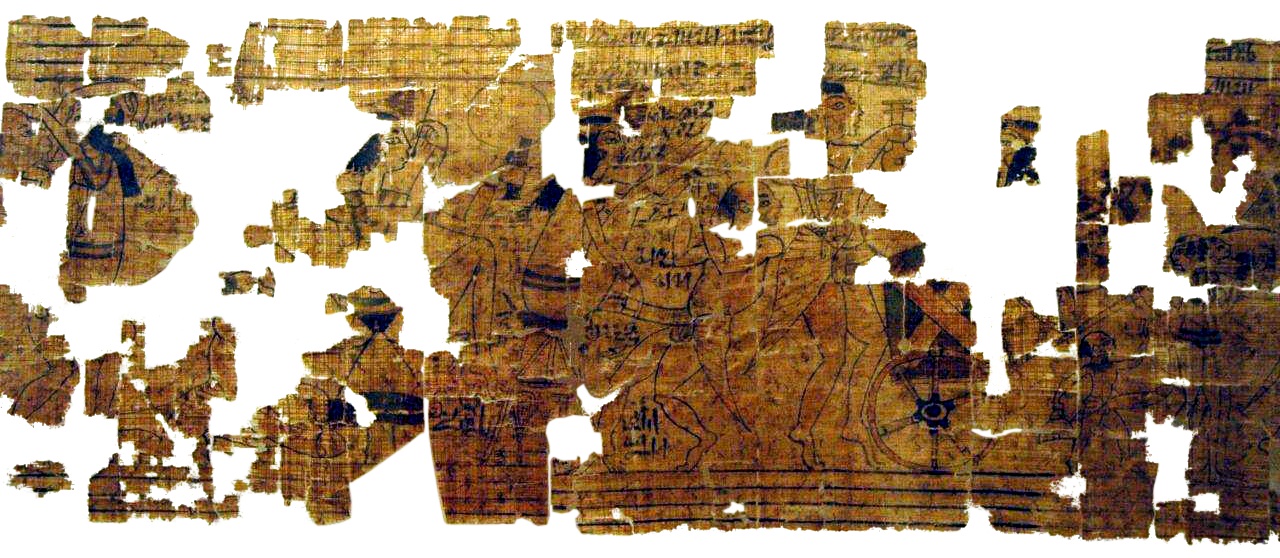

Image via Wikimedia Commons

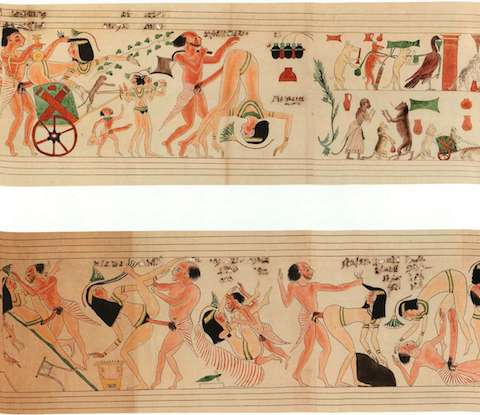

With the old joke about every generation thinking they invented sex, Listverse brings us the papyrus above, the oldest depiction of sex on record. Painted sometime in the Ramesside Period (1292–1075 B.C.E.), the fragments above—called the “Turin Erotic Papyrus” because of their “discovery” in the Egyptian Museum of Turin, Italy—only hint at the frank versions of ancient sex they depict (see a graphic partial reconstruction at the bottom of the post—probably NSFW). The number of sexual positions the papyrus illustrates—twelve in all—“fall somewhere between impressively acrobatic and unnervingly ambitious,” one even involving a chariot. Apart from its obvious fertility symbols, writes archaeology blog Ancient Peoples, the papyrus also has a “humorous and/or satirical” purpose, and probably a male audience—evidenced, perhaps, by its resemblance to 70’s porn: “the men are mostly unkempt, unshaven, and balding […], whereas the women are the ideal of beauty in Egypt.”

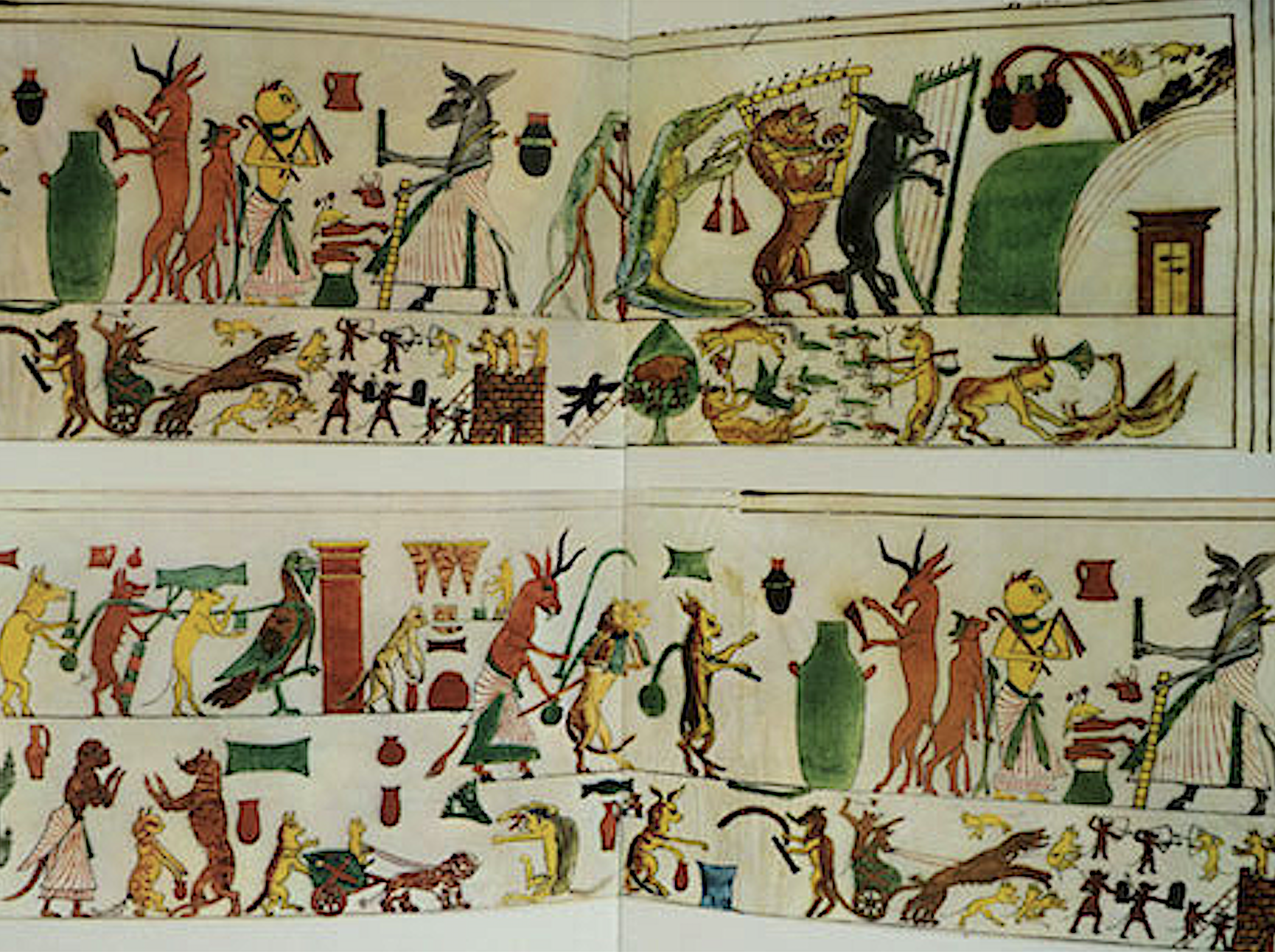

In fact the erotic portion of the papyrus was only made public in the 1970s. Egyptologists have known of the larger scroll, technically called “Papyrus Turin 55001” since the 1820s. On the right side of the papyrus (above) animals perform various human tasks as musicians, soldiers, and artisans. The artist meant this piece too as satire, Ancient Peoples alleges. Like ancient Roman and Greek satirical art, the animals may represent supposed archetypal aspects of the artists and tradesmen shown here. All very interesting, but of course the real interest in Papyrus Turin 55001 is of the prurient variety.

Egyptology student Caroline Seawright points us toward the rather lurid History Channel segment on the erotic papyrus, which calls the pictures “one of the most shocking sets of images in the whole of antiquity.” Against a perception of ancient Egyptians as “buttoned-up and repressed,” the video, and Seawright, detail the ways in which the culture reveled in a stylized ritual sexuality quite different from our own limited mores.

Sacred temple prostitutes held a privileged position and mythological narratives incorporated unbiased descriptions of homosexuality and transgenderism. Ancient Egyptians even expected to have sex after death, attaching fabricated organs to their mummies. The above applies mainly to a certain class of Egyptian. As archaeologist David O’Connor points out, the Turin Erotic Papyrus’ high “artistic merit” marks it as within the provenance of “an elite owner and audience.” You can find more detailed images from a different reconstruction of the erotic papyrus here.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2014.

Related Content:

An Ancient Egyptian Homework Assignment from 1800 Years Ago: Some Things Are Truly Timeless

Sex and Alcohol in Medieval Times: A Look into the Pleasures of the Middle Ages