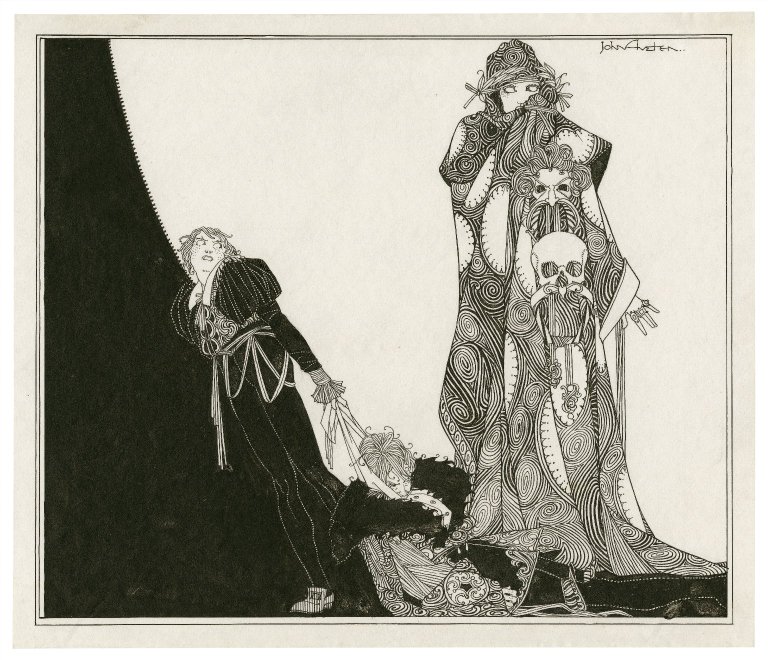

Image by J. G. Ballard, via the British Library

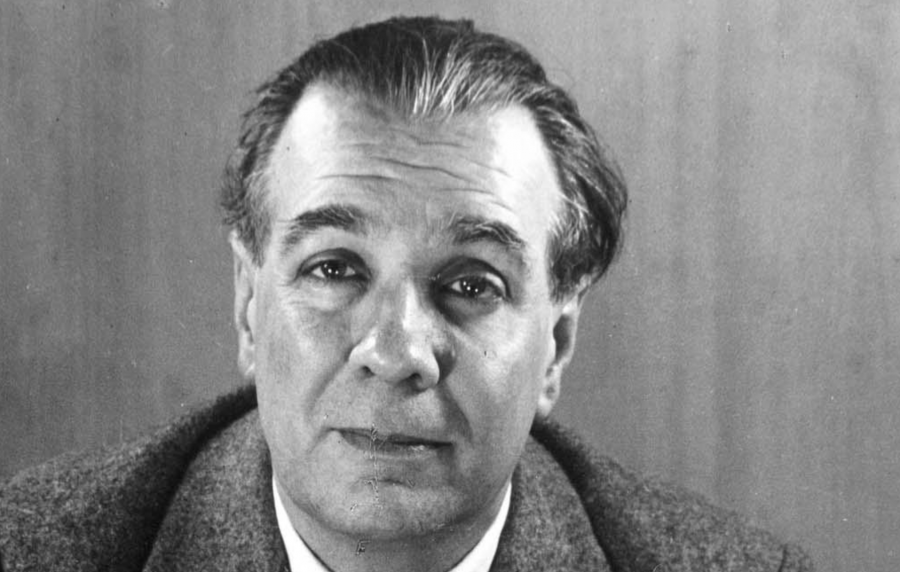

J.G. Ballard became famous for his 1985 autobiographical novel Empire of the Sun (later turned by Steven Spielberg into a major motion picture). Before that, he became well-known for his controversial, car-wreck-eroticizing 1973 novel Crash (later turned by David Cronenberg into a semi-major motion picture). Before that, he made cultural waves with the experimental 1970 collection of “condensed novels” The Atrocity Exhibition and the both post-apocalyptic and psychological Drowned World trilogy of the 1960s. Go just a bit deeper back into the Ballard canon and you find a work, in its way, even more daring still: 1958’s Project for a New Novel.

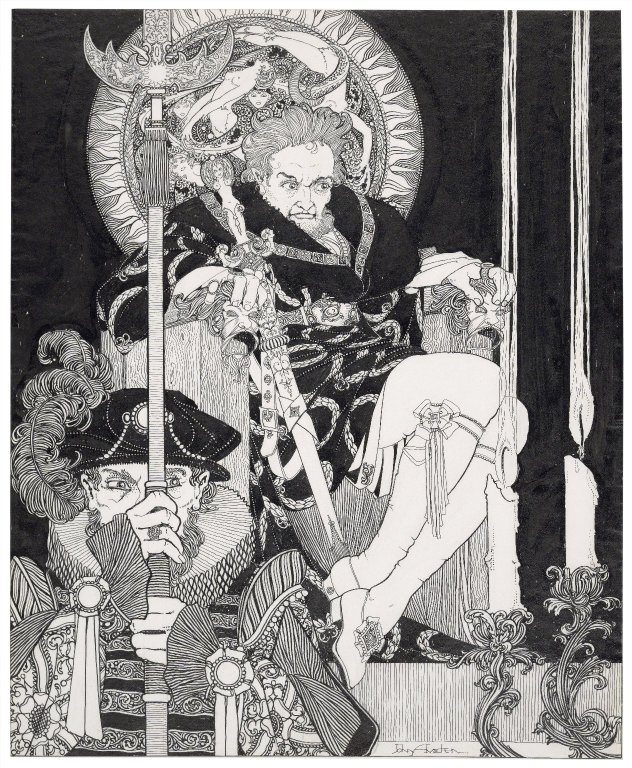

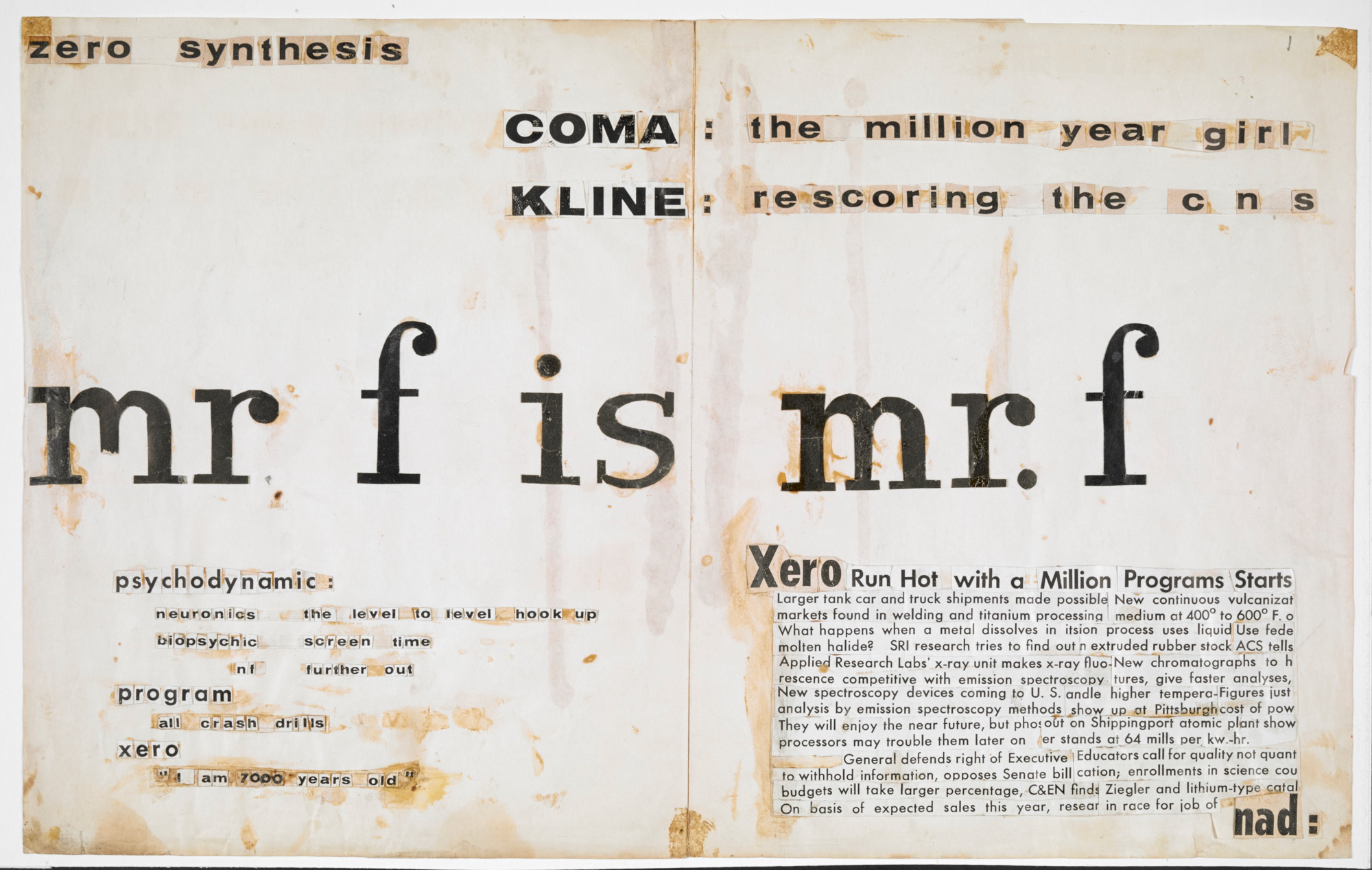

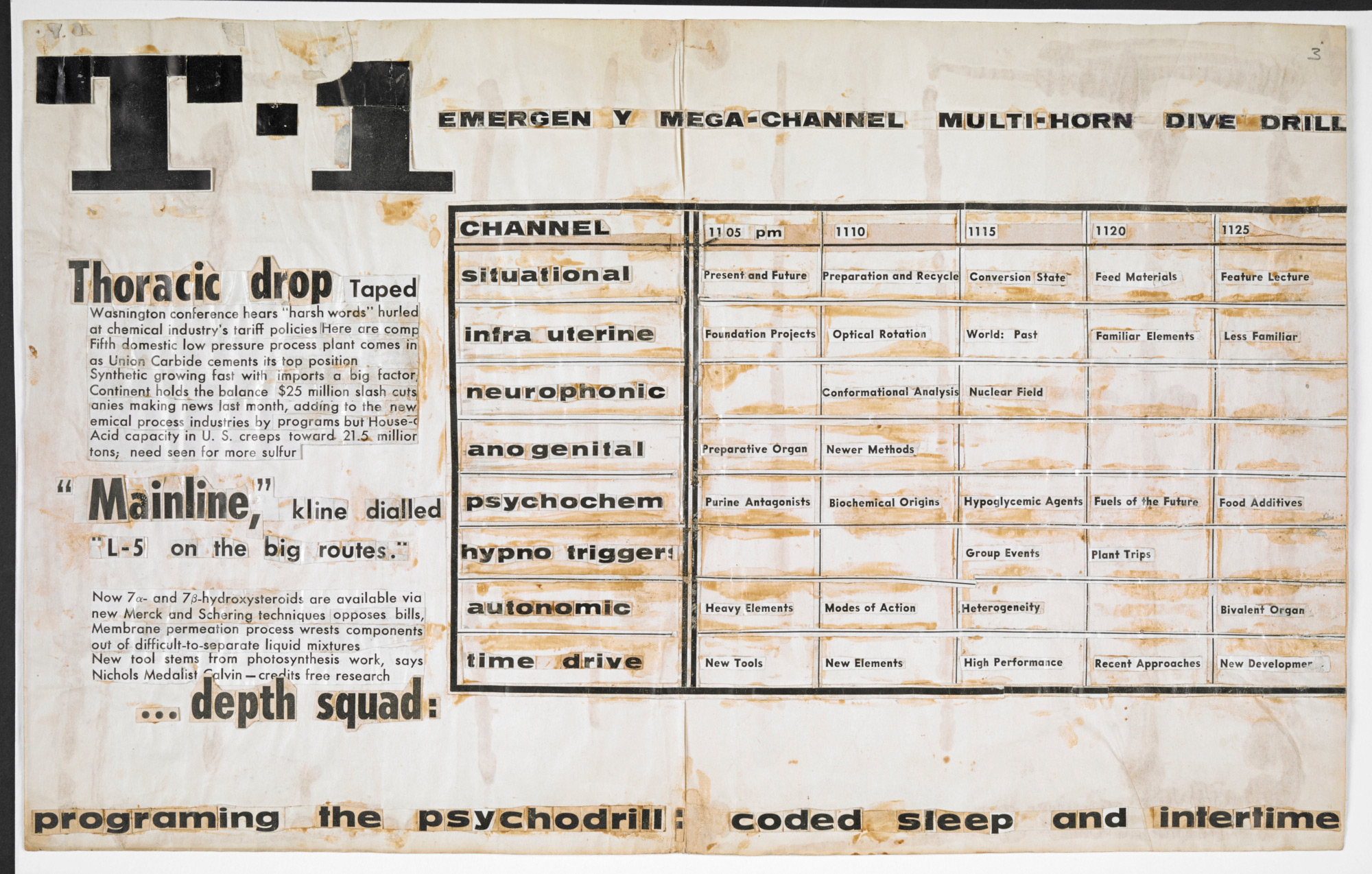

“Ballard formed the ‘novel’ from scientific and technical material cut from professional literature,” says the page at the British Library where you can see images of the work, the process of whose composition bears a resemblance to William Burroughs’ famous “cut-up writing” technique. “Letters, words and sentence fragments are pasted onto backing sheets with glue. Their design visually references everyday media, with headlines, body text and double-page spreads suggesting a magazine layout. Originally Ballard planned to display the work on billboards, as if it was a public advertisement.”

Ballard himself described the Project as “sample pages of a new kind of novel, entirely consisting of magazine-style headlines and layouts, with a deliberately meaningless text, the idea being that the imaginative content could be carried by the headlines and overall design, so making obsolete the need for a traditional text except for virtually decorative purposes.”

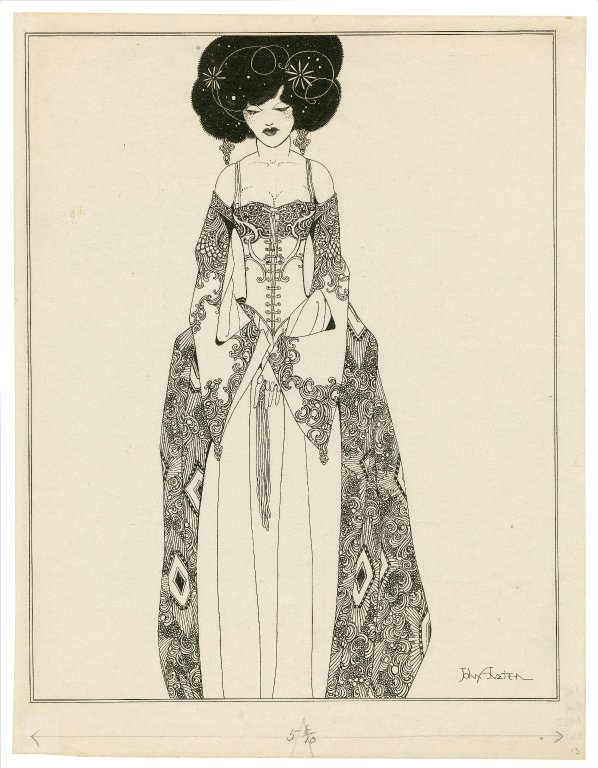

Image by J. G. Ballard, via the British Library

Employment at a London chemical society journal gave him access not just to photocopying facilities (then a rarity) but the magazine Chemical and Engineering News, which became his basic material: “I liked the stylish typography. I also like the scientific content, and used stories to provide the text of my novel. Curiously enough, far from being meaningless, the science news stories somehow become fictionalized by the headings around them.”

That quote comes from an article by Rick McGrath at jgballard.ca, who points out that “many of the characters and concerns in Project have resurfaced over the years” in his subsequent writings such as The Atrocity Exhibition and The Terminal Beach: “Ballard’s ‘collage of things’ spawned such characters as Coma, Kline and Xero, and such phrases as ‘the terminal beach’, ‘Mr F is Mr F’, ‘thoracic drop’ ‘intertime’ ‘T‑12’ and many more Ballardian tropes now familiar to his readers today.”

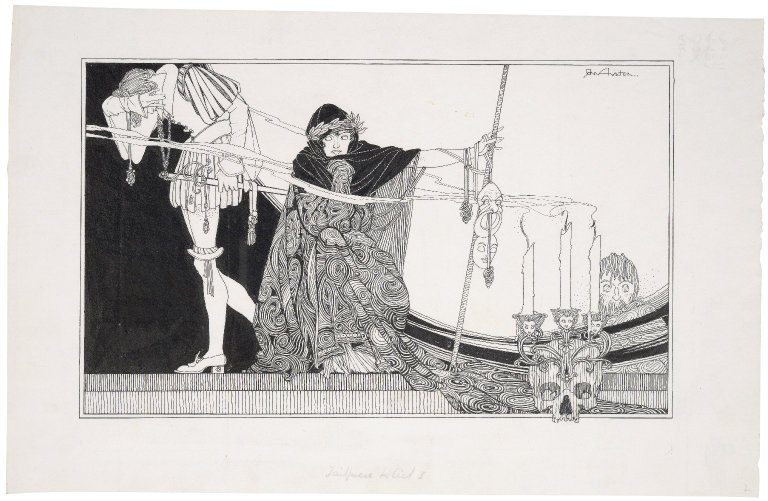

Though Ballard’s work remained imaginative in a way that no other writer has replicated, he never, after the Project for a New Novel and the pieces of 1970s follow-up Advertiser’s Announcements (“ ‘ads’ in the same sense that Project For A New Novel is a ‘novel‘”), got so experimental again. “Fascinated with the causality of time, Ballard’s first step is to remove it. Bored with action/reaction, Ballard inverts it,” writes McGrath. “Unwilling to accept the fictions of the world, Ballard creates a personal reality. The result is an autopsy report, or a box of tools, or a lineup of service station attendants at a police station. It’s up to you to make a kind of personal sense of it all” — a bit like the modern world itself.

via The Scofield

Related Content:

The Very First Film of J.G. Ballard’s Crash, Starring Ballard Himself (1971)

Sci-Fi Author J.G. Ballard Predicts the Rise of Social Media (1977)

William S. Burroughs on the Art of Cut-up Writing

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.