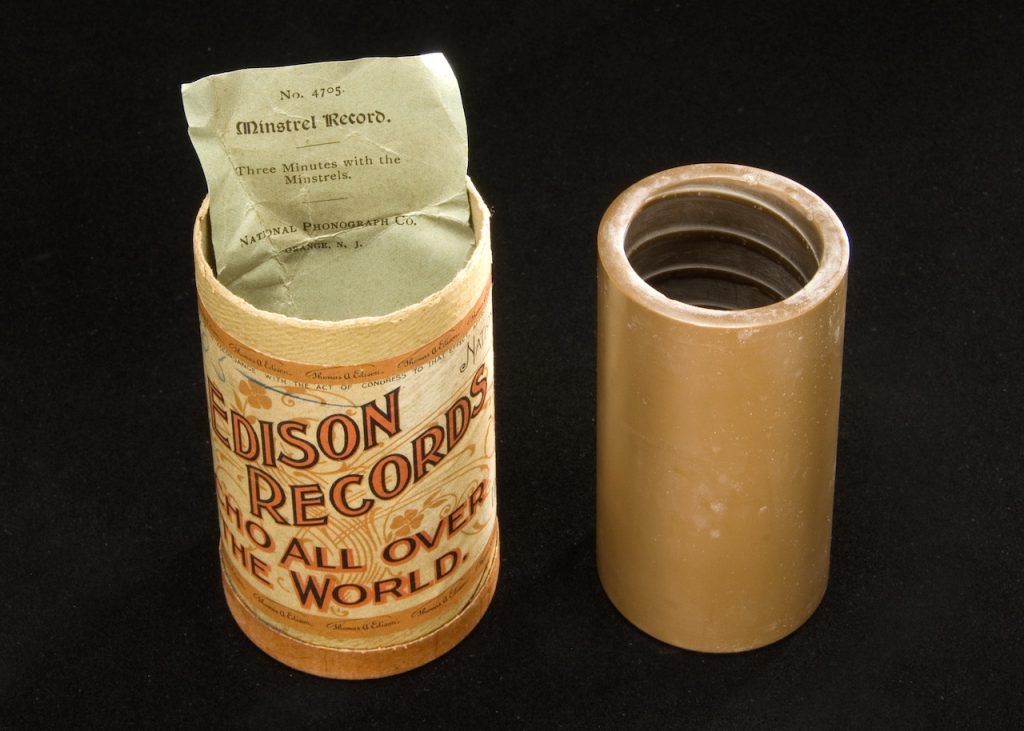

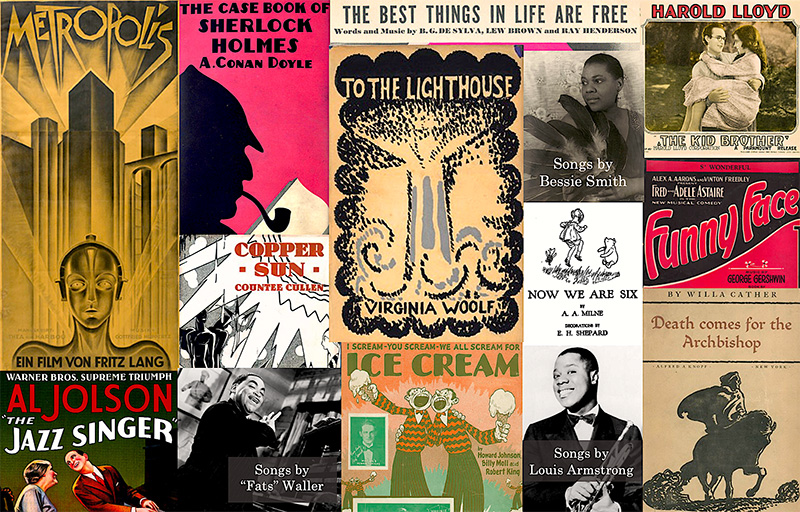

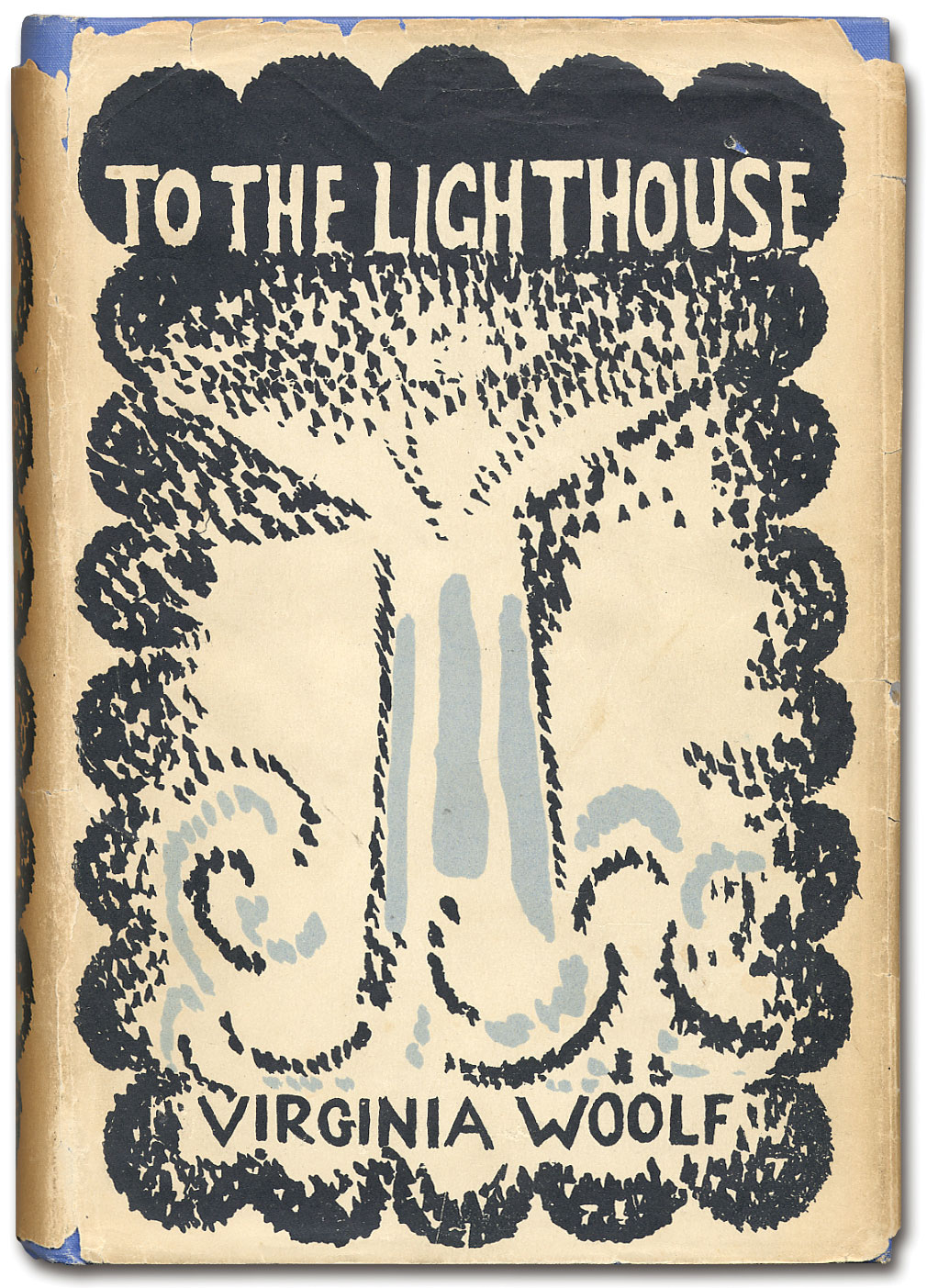

We may have yet to develop the technology of time travel, but recorded music comes pretty close. Those who listen to it have experienced how a song or an album can, in some sense, transport them right back to the time they first heard it. But older records also have the much stranger power to conjure up eras we never experienced. You can musically send yourself as far back as the nineteen-twenties with the above Youtube playlist of digitized 78 RPM records from the George Blood collection.

George Blood is the head of the audio-visual digitization company George Blood Audio, which has been participating in the Internet Archive’s Great 78 Project. “The brainchild of the Archive’s founder, Brewster Kahle, the project is dedicated to the preservation and discovery of 78rpm records,” writes The Vinyl Factory’s Will Pritchard.

The piece quotes Blood himself as saying that his company has been digitizing five to six thousand records per month with the ambitious goal of creating a “reference collection of sound recordings from the period of approximately 1880 to 1960.” He said that five years ago. Today, the Internet Archive’s George Blood collection contains more than 385,000 records free to stream and download.

The 78 having been the most popular recorded-music format in the first few decades of the twentieth century, George Blood L.P. and the Great 78 Project as a whole have had plenty of material to work with. In the large archive built up so far you’ll find plenty of obscurities — the Youtube playlist at the top of the post can get you acquainted with the likes of Eric Whitley and the Green Sisters, Tin Ear Tanner and His Back Room Boys, and Douglas Venable and His Bar X Ranch Hands — but also the work of musicians who remain beloved today. For the 78 was the medium through which many listeners enjoyed the big-band hit of Glenn Miller, or discovered jazz as performed by legends like Louis Armstrong and Billie Holiday. To know their music most intimately, one would perhaps have needed to hear them in the actual nineteen-thirties, but this is surely the next best thing.

Related content:

200,000+ Vintage Records Being Digitized & Put Online by the Boston Public Library

Rare Arabic 78 RPM Records Enter the Public Domain

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.