photo by Céline Vidal

“Where’re you from?” one character asks another on the Firesign Theatre’s classic 1969 album How Can You Be in Two Places at Once When You’re Not Anywhere at All. “Nairobi, ma’am,” the other replies. “Isn’t everybody?” Like most of the countless multi-layered gags on their albums, this one makes a cultural reference, presumably to the discoveries made by famed paleoanthropologists Louis and Mary Leakey over the previous 20 years. Their discovery of fossils in Kenya and elsewhere did much to advance the thesis that humankind evolved in Africa, and that the process was happening more than 1.75 million years before.

Like all scientific breakthroughs, the Leakeys’ work only prompted more questions — or rather, created more opportunities for refining and adding detail to the relevant body of knowledge. Subsequent digs all over Africa have produced further evidence of how far our species and its predecessors go back, and where exactly the evolutionary progress happened.

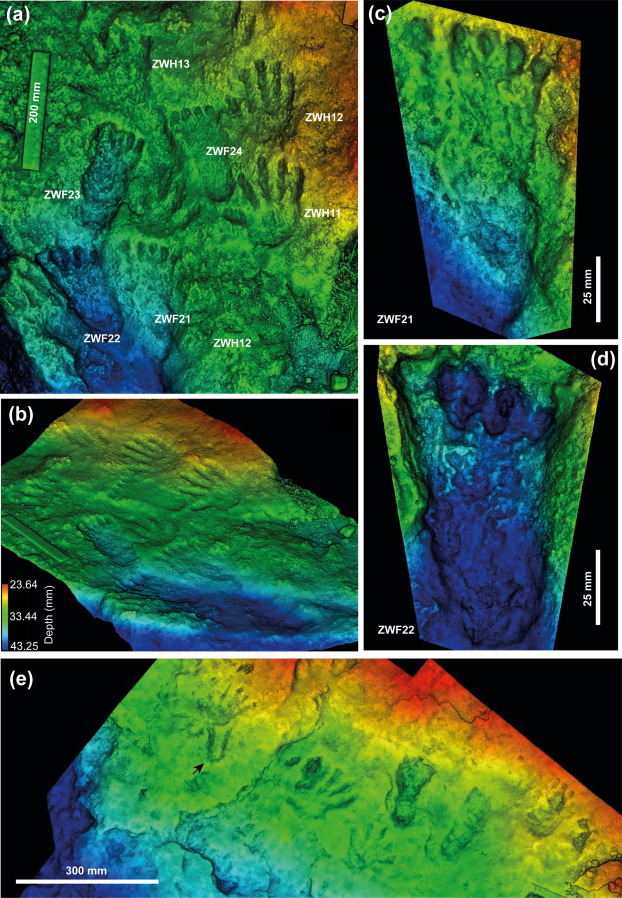

Just this month, Nature published a new paper on the “age of the oldest known Homo sapiens from eastern Africa.” These new findings about known fossils, originally discovered in southwestern Ethiopia in 1967, suggest that the time has come for another revision of the long pre-history of humanity.

photo by Céline Vidal

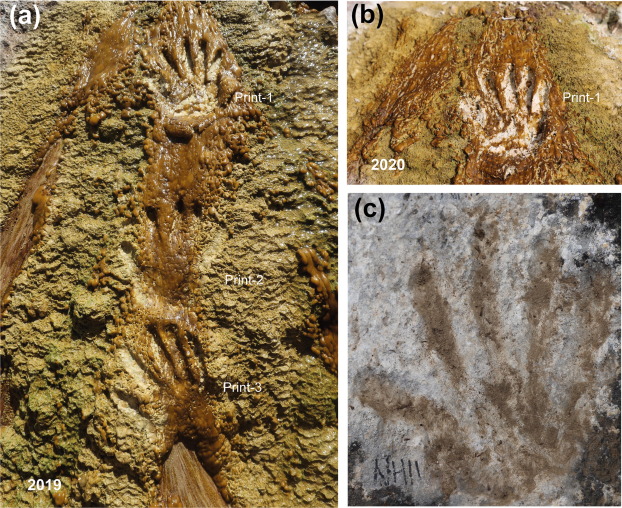

The paper’s authors, writes Reuters’ Will Dunham, “used the geochemical fingerprints of a thick layer of ash found above the sediments containing the fossils to ascertain that it resulted from an eruption that spewed volcanic fallout over a wide swathe of Ethiopia roughly 233,000 years ago.” These fossils “include a rather complete cranial vault and lower jaw, some vertebrae and parts of the arms and legs.” After their initial discovery by the late Richard Leakey, son of Louis and Mary (and a man genuinely from Nairobi, born and raised), the fossils buried by this prehistoric Vesuvius were previously believed to be “no more than about 200,000 years old.”

Dunham quotes the paper’s lead author, University of Cambridge volcanologist Celine Vidal, as saying this discovery aligns with “the most recent scientific models of human evolution placing the emergence of Homo sapiens sometime between 350,000 to 200,000 years ago.” Though Vidal and her team’s analysis of the ash’s geochemical composition has determined the minimum age of Omo I, as these fossils are known, the maximum age remains an open question. Or at least, it awaits the efforts of researchers to date the “ash layer below the sediment containing the fossils” and render a more precise estimate. And when that’s established, it will then, ideally, become material for the next big absurdist comedy troupe.

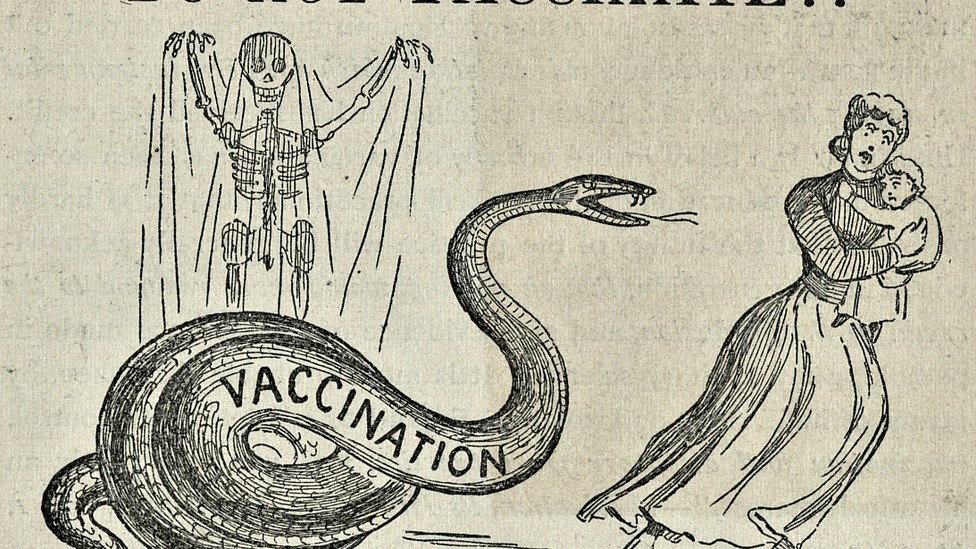

via Hyperallergic

Related Content:

Where Did Human Beings Come From? 7 Million Years of Human Evolution Visualized in Six Minutes

Richard Dawkins Explains Why There Was Never a First Human Being

How Humans Migrated Across The Globe Over 200,000 Years: An Animated Look

The Life & Discoveries of Mary Leakey Celebrated in an Endearing Cutout Animation

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.