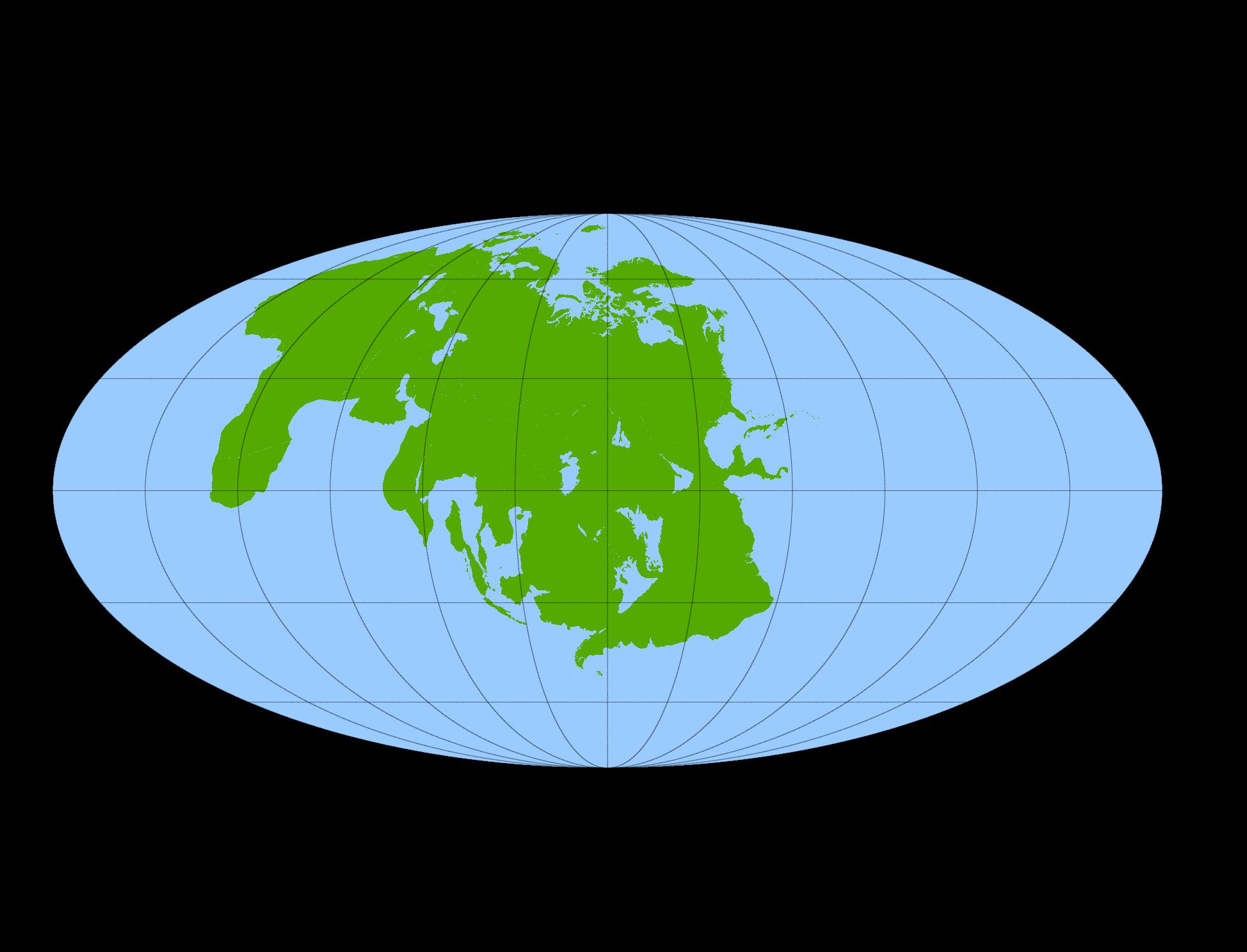

Most of us now accept the idea that all of Earth’s continents were once part of a single, enormous land mass. That wasn’t the case in the early nineteen-tens, when the geologist Alfred Wegener (1880–1930) first publicized his theory of not just the supercontinent Pangea, but also of the phenomenon of continental drift that caused it to break apart into the series of shapes we all know from classroom world maps. But as humorously explained in the Map Men video above, Wegener didn’t live to see these ideas convince the world. Only after his death did other scientists figure out just how the geological churning under the planet’s surface caused the continents to drift apart in the first place.

With that information in place, Pangea no longer seemed like the crackpot notion it had when Wegener initially proposed it. Less widely appreciated, even today, is the determination that, as the Map Men put it, “Pangea, far from being the original supercontinent, was actually the eleventh to have formed in Earth’s history.”

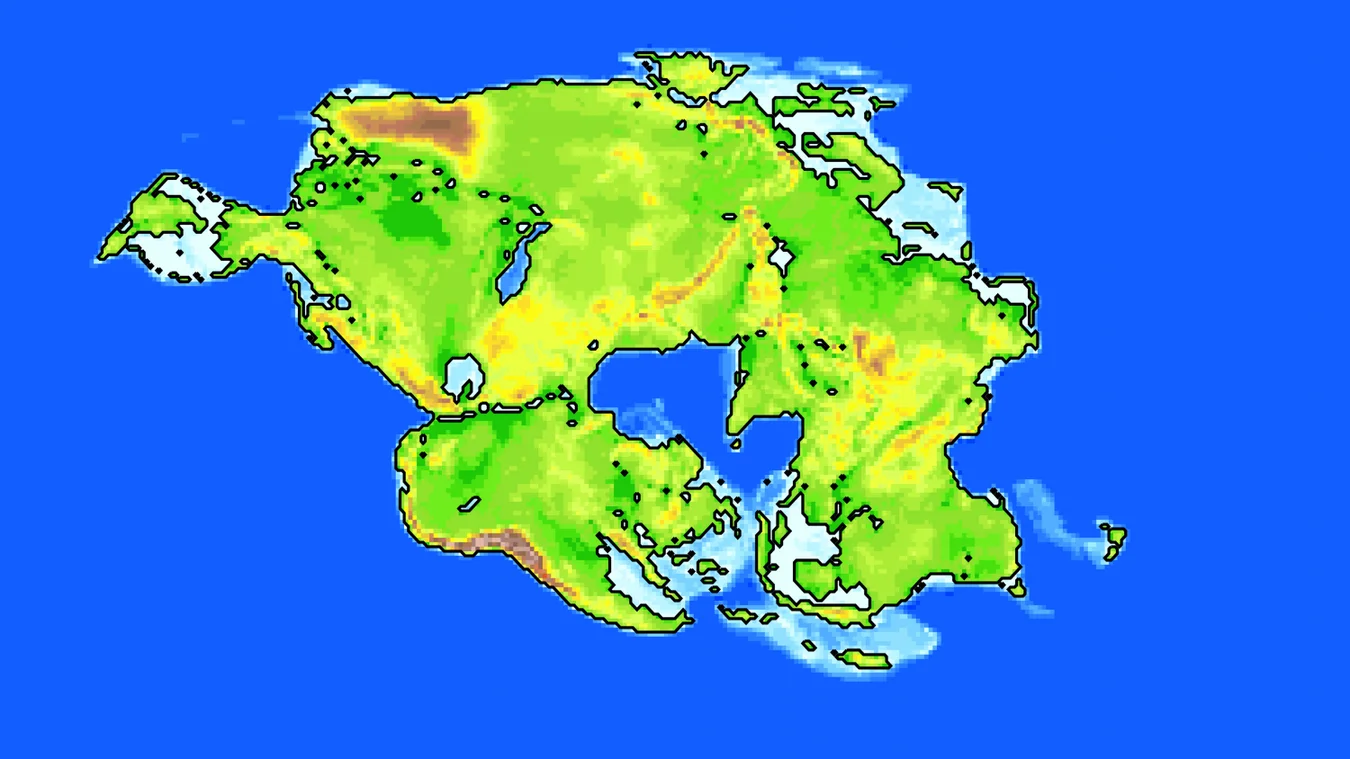

It seems that the continents have been cyclically breaking apart and coming together again, with no sign of the process stopping. When, then, will we next find ourselves back on a supercontinent? Perhaps in 250 million years or so, according to the “Novopangea” model explained in the video, which has the Pacific ocean closing up as Australia slots into East Asia and North America while Antarctica drifts north.

Other models also exist, including Aurica, “where Eurasia splits in half, and both the Pacific and Atlantic oceans close up”; Pangea Ultima, “where Britain gets closer to America”; and Amasia, “where all the continents congregate around the North Pole, except Antarctica” (whose drift patterns make it seem like “the laziest continent”). At this kind of time scale, small changes in the basic assumptions can result in very different-looking supercontinents indeed, not that any of us will be around to see how the next Pangea really takes shape. Nevertheless, in this age when we can hardly go a week without encountering predictions of humanity’s imminent extinction, it’s refreshing to find a subject that lets us even consider looking a quarter-billion years down the road.

Related Content:

Map Showing Where Today’s Countries Would Be Located on Pangea

A Web Site That Lets You Find Your Home Address on Pangea

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.