In the last year, screenwriter Todd Alcott’s hobby has blown up into a legit side career.

This Etsy seller isn’t peddling kombucha SCOBYs, letter pressing new baby announcements, or repurposing old barns for use as cutting boards.

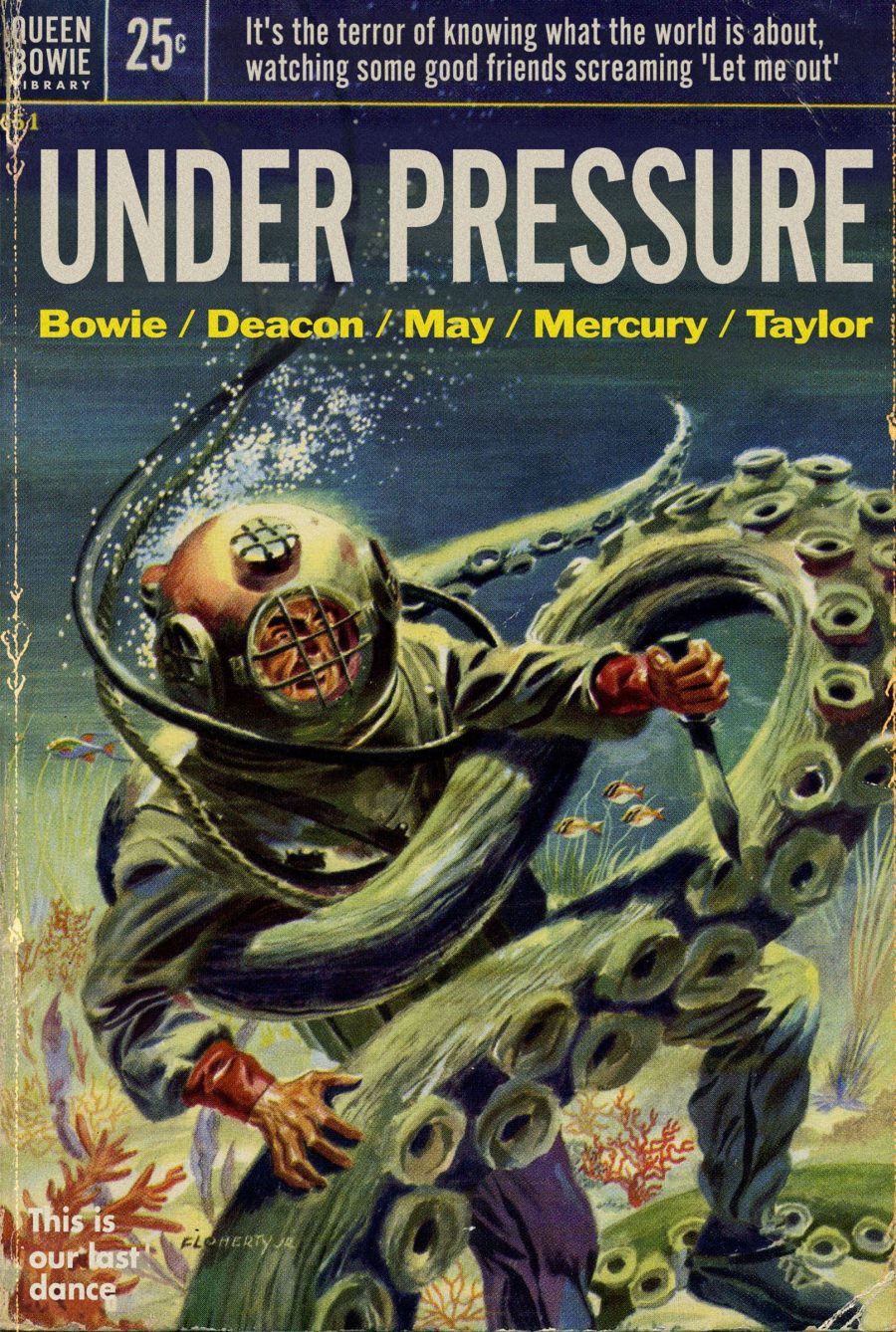

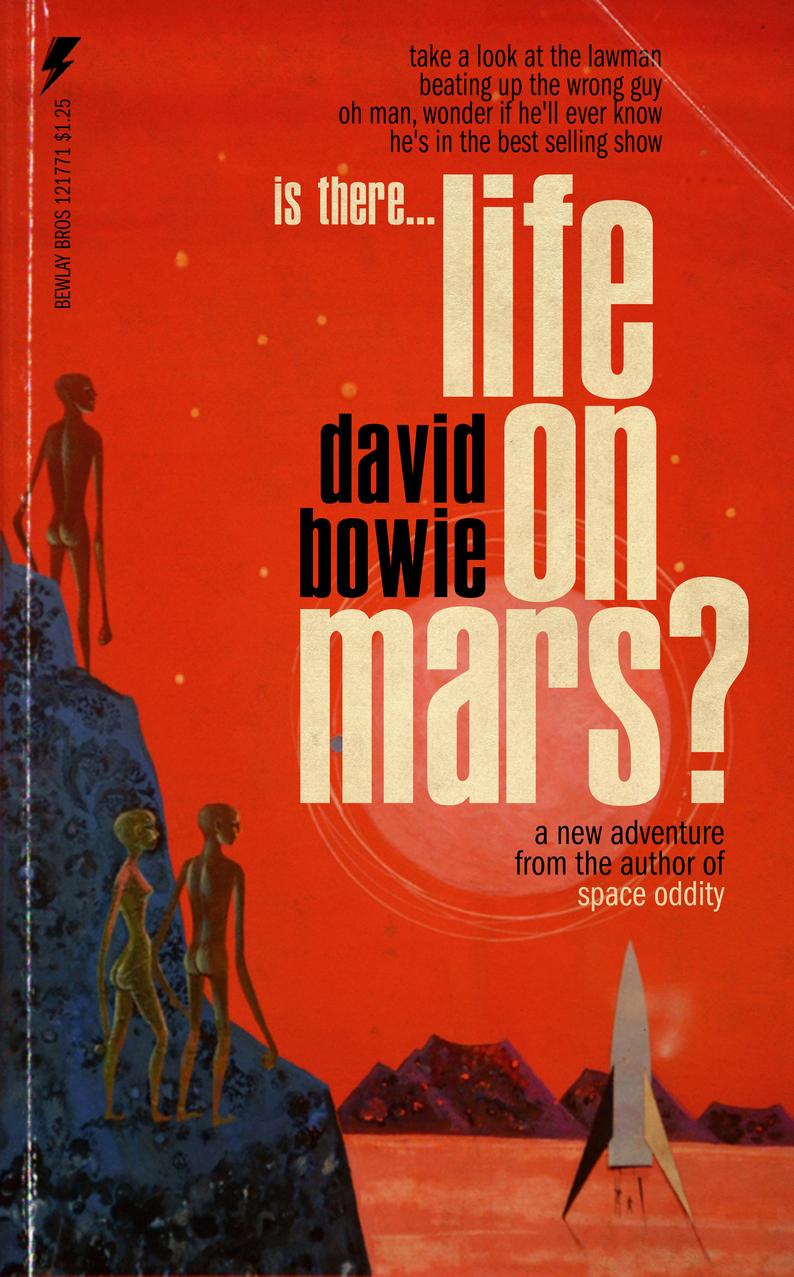

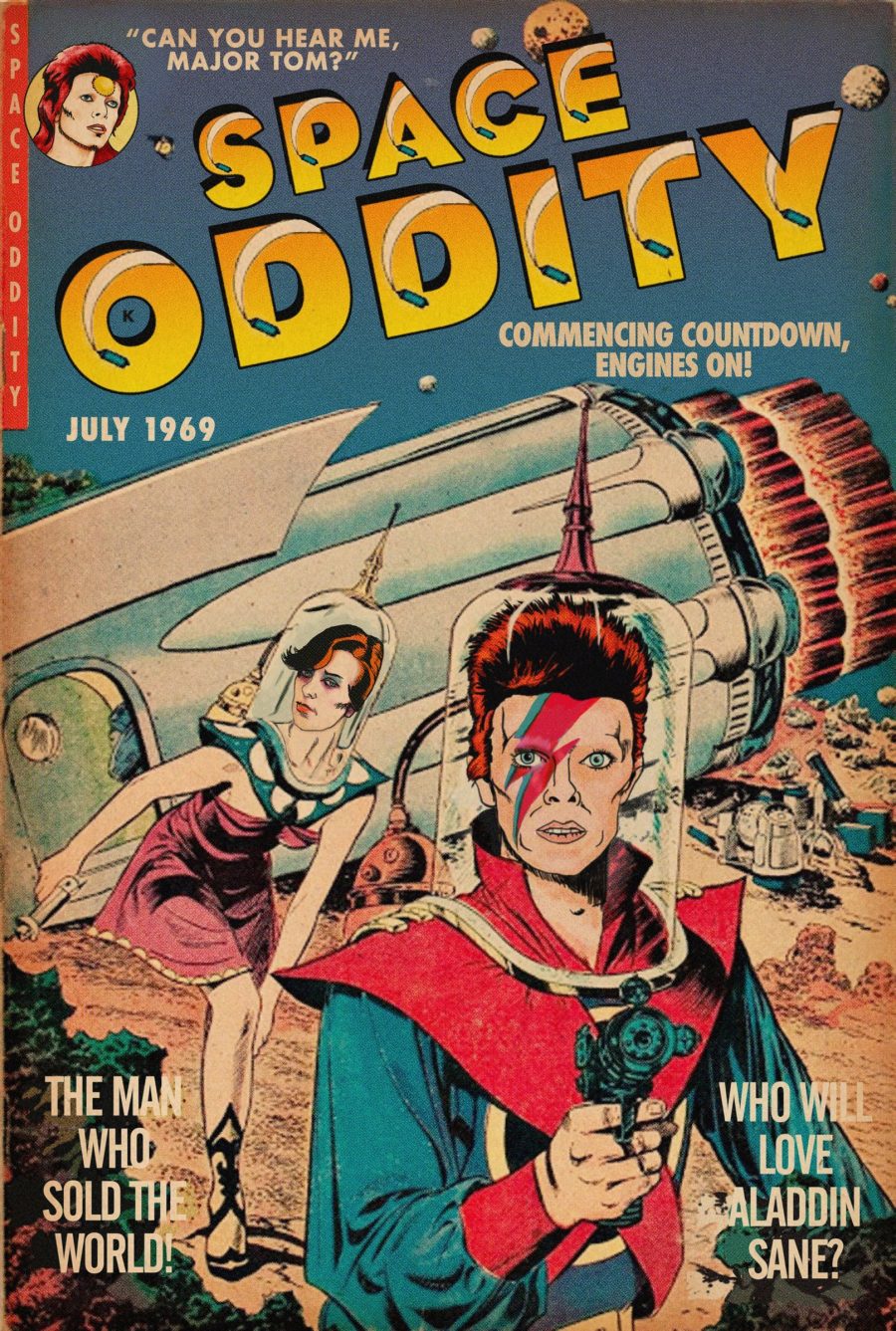

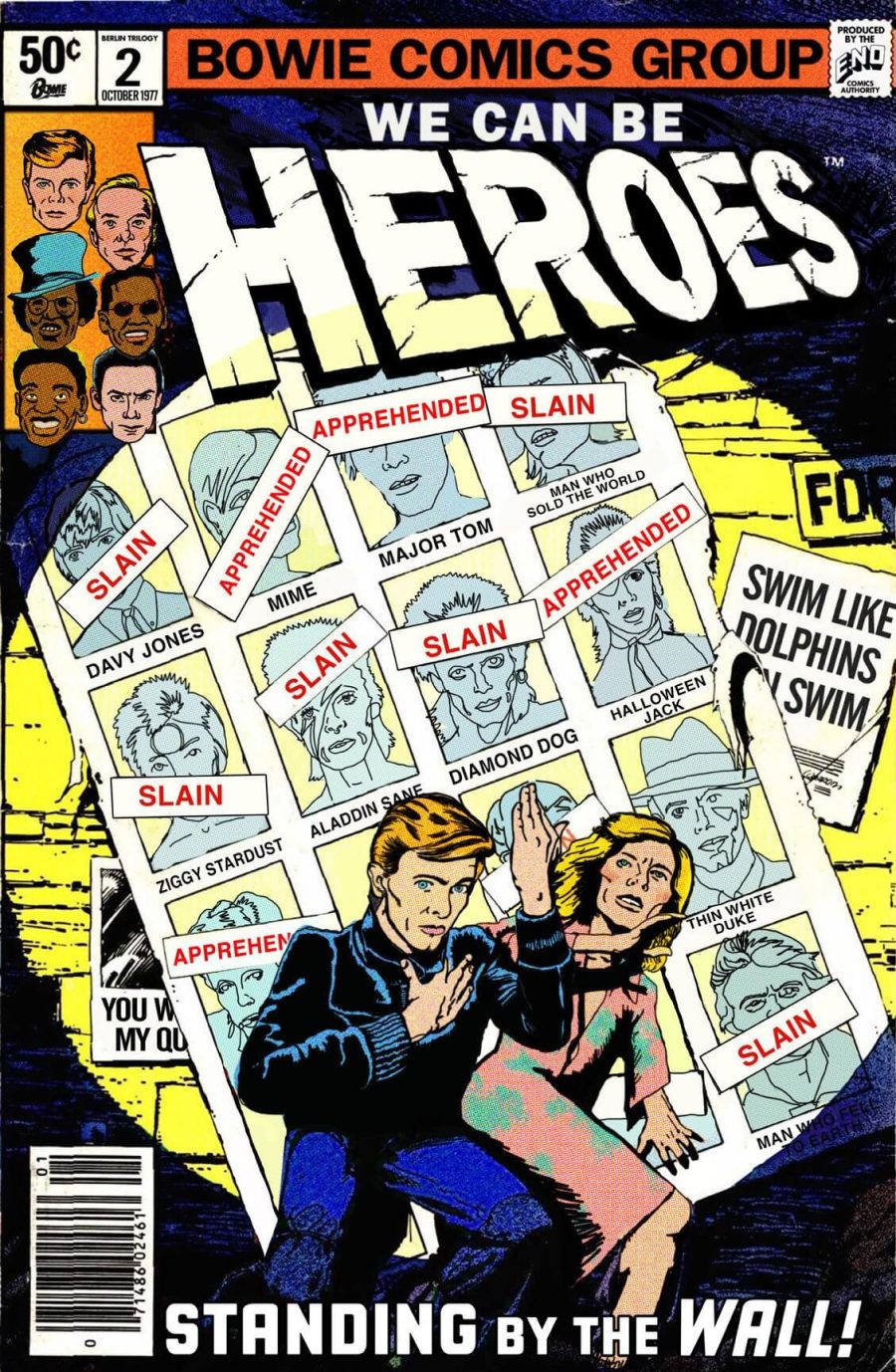

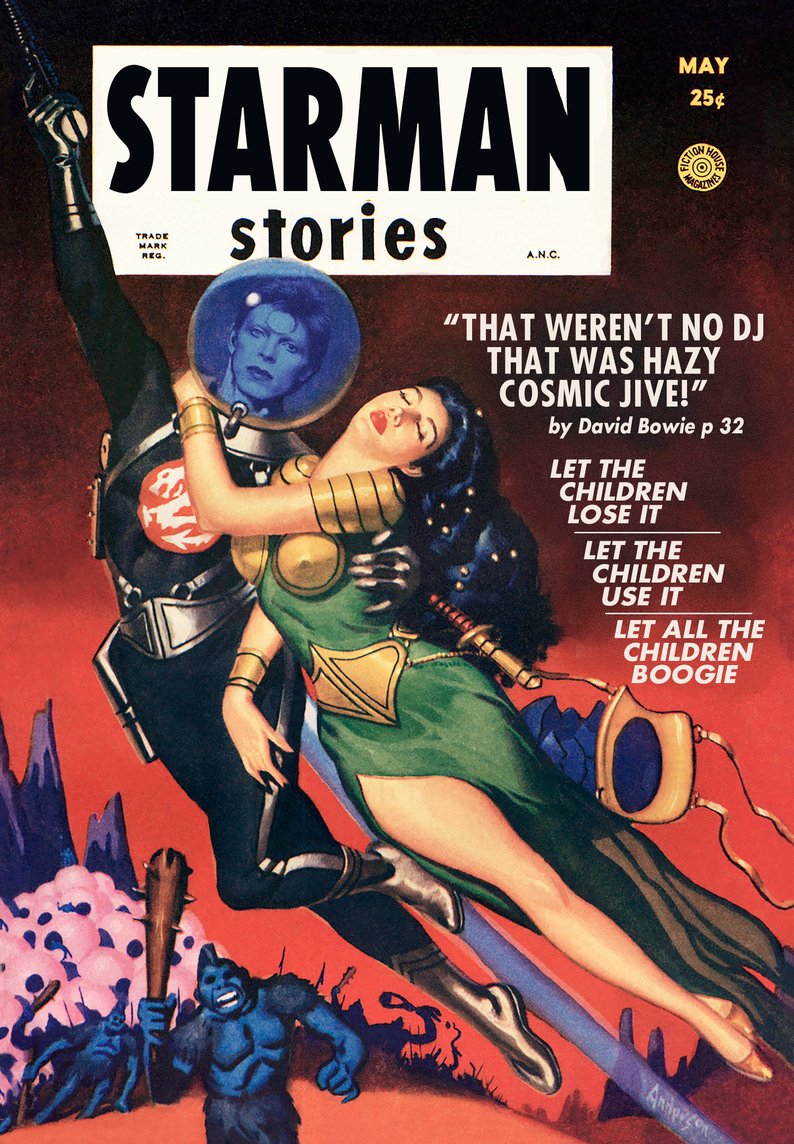

No, Alcott’s crafty fortunes fall squarely at the intersection of pulp fiction and rock and roll, with classic song titles, lyrics, and other cunning references replacing the cover text of pre-existing vintage paperbacks.

David Bowie’s lifelong fascination with space travel, tortured anti heroes, and outrageous fashion make him a natural fit with Alcott’s ongoing project, which has lavished similar attention on such luminaries as Bob Dylan, Radiohead, Talking Heads, and Elvis Costello.

As Alcott, who conceives of his mash ups as tributes to his long time musical favorites, told Open Culture:

Bowie dressed as an androgynous alien, went out onstage and told his audience “You’re not alone, give me your hands,” I can’t think of a more encompassing gesture to a misfit. No matter how weird you were in your community, you would always find someone like you at a Bowie concert. During a time of my life when I felt incredibly isolated and alone, (Bowie was one of) the key artists who made me feel like I was part of a bigger world, an artistic continuum.

Meanwhile, Alcott is tending to another continuum by posthumously pairing such late greats as Bowie and Queen’s Freddie Mercury (“co-author” of the deep sea-themed Under Pressure cover, above) with the sort of adventurous, occasionally steamy reading material that were among the hallmarks of their 1950s’ boyhoods.

Many of these items have found their way to used book and thrift stores, where, tattered and worn, they provide a vast trove for someone like Alcott, who browses with his favorite acts’ catalogues deeply imprinted on his mental hard drive.

It must’ve been a grand day when he happened across the above 1970s sci fi cover. A few deft tweaks, and Life on Mars, a nonexistent “new adventure from the author of Space Oddity,” was born.

(Hardcore fans, take note of the doctored publisher in the upper left corner)

Heroes, which takes its inspiration from the 1981 X‑Men comic Days of Future Past, is crammed full of such Easter eggs. Can you spot them all?

What a fitting tribute to the Starman’s enduring hold on the public’s imagination.

Browse Todd Alcott’s Bowie-themed pulp fiction collection in his Etsy shop.

Related Content:

The Art Collection of David Bowie: An Introduction