We don’t often think of the Beats as family men, and that’s because the most prominent of them weren’t, except William Burroughs for a time (a tragic story or two for another day). But friends of Ginsberg and Kerouac like Lucien and Francesca Carr and Robert and Mary Frank brought children into the poets’ lives, and you can see them all above, relaxing at the Harmony Bar & Restaurant in New York’s East Village in 1959.

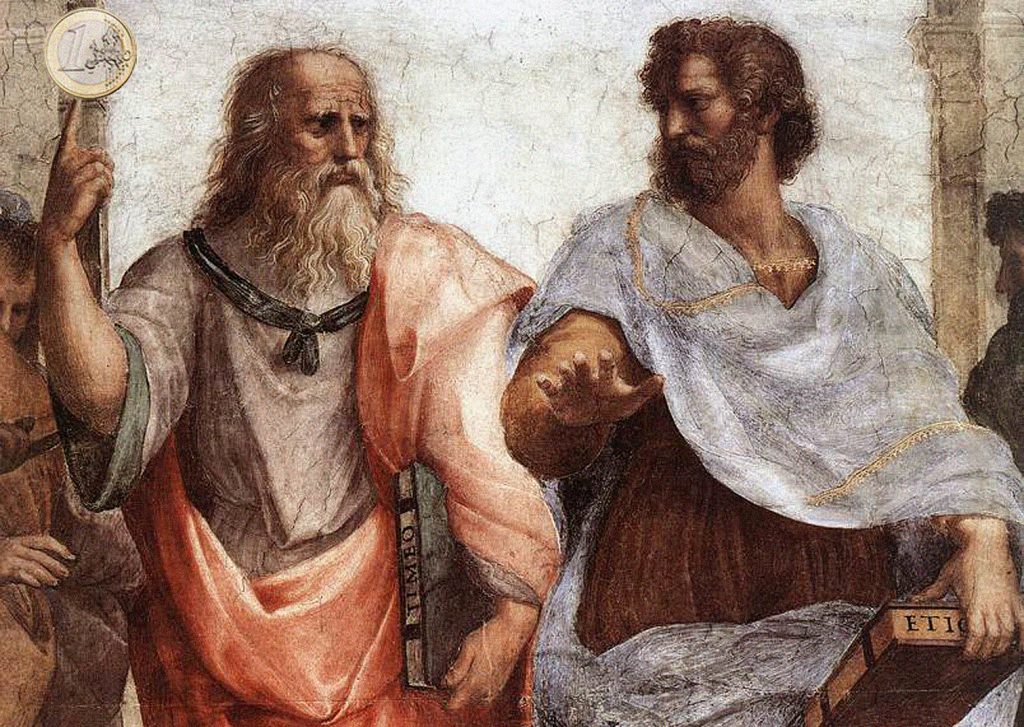

This rare silent footage unites the three Carr and two Frank children in a rare appearance of the Beats together on film. The mustachioed Lucien Carr —a character with his own dark story—can be seen seated next to Kerouac. The Franks, père and mère, were both artists in their own right—London-born Mary a trained dancer, sculptor, and painter, and Robert an important American photographer and documentary filmmaker.

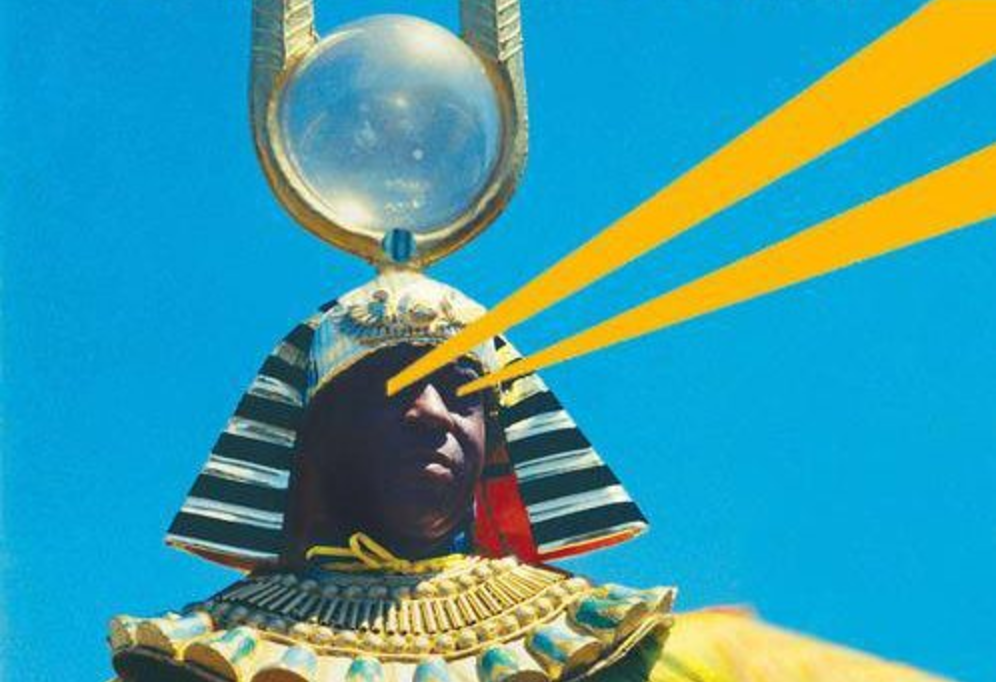

Dangerous Minds speculates that it’s Robert Frank behind the camera, both because we don’t see him in front of it and because Frank would that same year direct the short film Pull My Daisy (above), featuring both Ginsberg and Kerouac and adapted from Kerouac’s play Beat Generation. (Frank apparently denies he shot the footage at the top). Pull My Daisy also includes famous Beats like Gregory Corso, musician David Amram, and Ginsberg’s partner, poet Peter Orlovsky. In a previous post on that film, Open Culture’s Colin Marshall described it as crafted with “great deliberateness, albeit the kind of deliberateness meant to create the impression of thrown-together, ramshackle spontaneity.”

To learn more about the Beats’ appearances on film—as themselves, in character, and through their adapted work, see this excellent filmography. And just above, watch a mash-up of most of those various cinematic appearances in a trailer produced by Cinefamily for the IFC and Sundance series “Beats on Film.”

via The Wall Breakers/Dangerous Minds

Related Content:

Pull My Daisy: 1959 Beatnik Film Stars Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, Shot by Robert Frank

William S. Burrough’s Avant-Garde Movie ‘The Cut Ups’ (1966)

Bob Dylan and Allen Ginsberg Visit the Grave of Jack Kerouac (1975)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness