We hear many tragic stories of disappearing indigenous languages, their last native speakers dying out, and the symbolic and social worlds embedded in those languages going with them, unless they’re recorded (or recovered) by historians and archived in museums. Such reporting, sad but necessary, can sometimes obscure the millions of living indigenous language speakers who suffer from systemic neglect around the world.

The situation is beginning to change. The UN has called 2019 the Year of Indigenous Languages, not only to raise awareness of the loss of language diversity, but also to highlight the world’s continued linguistic richness. A 2015 World Bank report estimated that 560 different languages are spoken in Latin America alone.

The South American language Quechua—once a primary language of the Incan empire—claims one of the highest number of speakers: 8 million in the Andean region, with 4 million of those speakers in Peru. Yet, despite continued widespread use, Quechua has been labeled endangered by UNESCO. “Until recently,” writes Frances Jenner at Latin American Reports, “the Peruvian government had few language preservation policies in place.”

“In 2016 however, TV Perú introduced a Quechua-language daily news program called Ñuqanchik meaning ‘All of us,’ and in Cusco, the language is starting to be taught in some schools.” Now, Peruvian scholar Roxana Quispe Collantes has made history by defending the first doctoral thesis written in Quechua, at Lima’s 468-year old San Marco University. Her project examines the Quechuan poetry of 20th century writer Alencastre Gutiérrez.

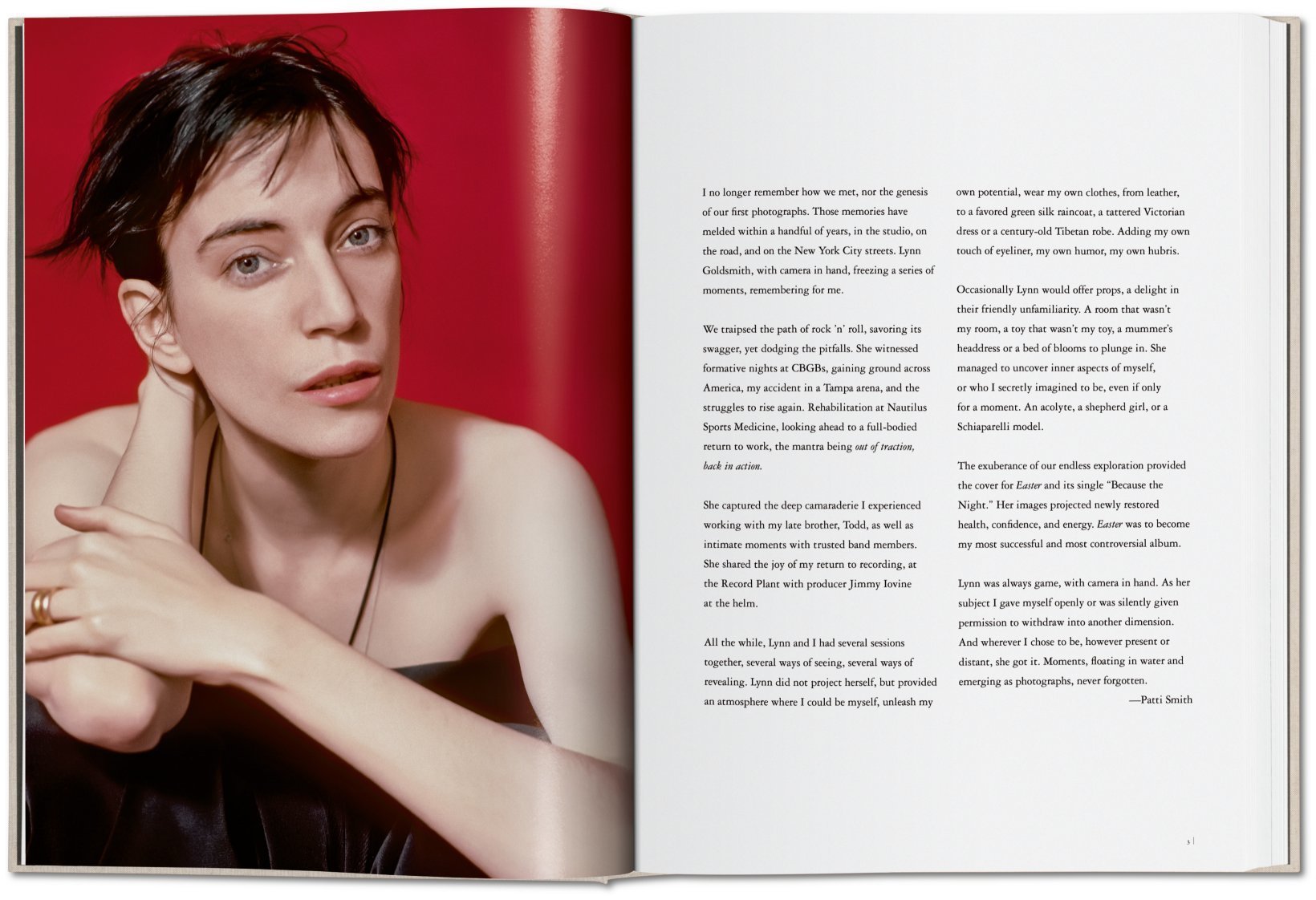

Collantes began her thesis presentation with a traditional thanksgiving ceremony,” writes Naveen Razik at NITV News, “and presented her study titled Yawar Para (Blood Rain),” the culmination of seven years spent “traveling to remote communities in the mountainous Canas region” to “verify the words and phrases used in Gutiérrez’s works.” The examiners asked her questions in Quechua during the nearly two hour examination, which you can see above.

The project represents a significant personal achievement for Collantes who “grew up speaking Quechua with her parents and grandparents in the Acomayo district of Cusco,” reports The Guardian. Collante’s work also represents a step forward for the support of indigenous language and culture, and the recognition of Quechua in particular. The language is foundational to South American culture, giving Spanish—and English—words like puma, condor, llama, and alpaca.

But it is “rarely—if ever—heard on national television or radio stations.” Quechua speakers, about 13% of Peruvians, “are disproportionately represented among the country’s poor without access to health services.” The stigma attached to the language has long been “synonymous with discrimination” and “social rejection” says Hugo Coya, director of Peru’s television and radio institute and the “driving force” behind the new Quechua news program.

Collantes’ work may be less accessible to the average Quechua speaker than TV news, but she hopes that it will make major cultural inroads towards greater acceptance. “I hope my example will help to revalue the language again and encourage young people, especially young women, to follow my path, “she says. “My greatest wish is for Quechua to become a necessity once again. Only by speaking it can we revive it.” Maybe in part due to her extensive efforts, UNESCO can take Quechua off its list of 2,860 endangered languages.

Related Content:

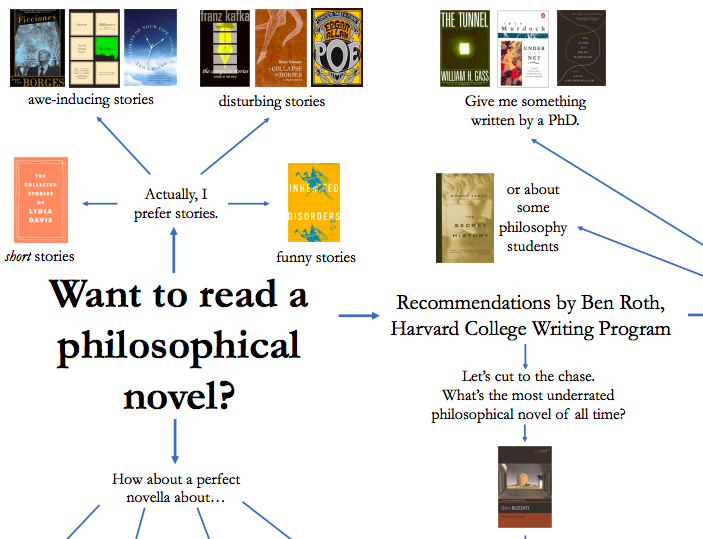

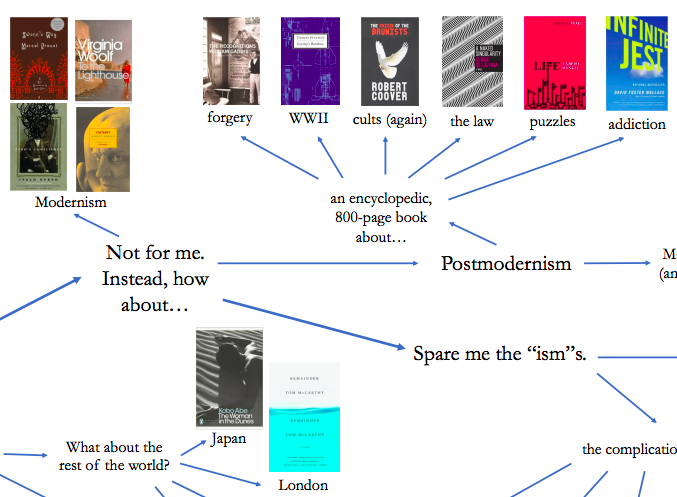

The Tree of Languages Illustrated in a Big, Beautiful Infographic

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness