One of my very first acts as a new New Yorker many years ago was to make the journey across three boroughs to Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx. My purpose: a pilgrimage to Herman Melville’s grave. I came not to worship a hero, exactly, but—as Fordham University English professor Angela O’Donnell writes—“to see a friend.” Professor O’Donnell goes on: “It might seem presumptuous to regard a celebrated 19th-century novelist so familiarly, but reading a great writer across the decades is a means of conducting conversation with him and, inevitably, leads to intimacy.” I fully share the sentiment.

I promised Melville I would visit regularly but, alas, the pleasures and travails of life in the big city kept me away, and I never returned. No such petty distraction kept away a friend-across-the-ages of another 19th-century American author.

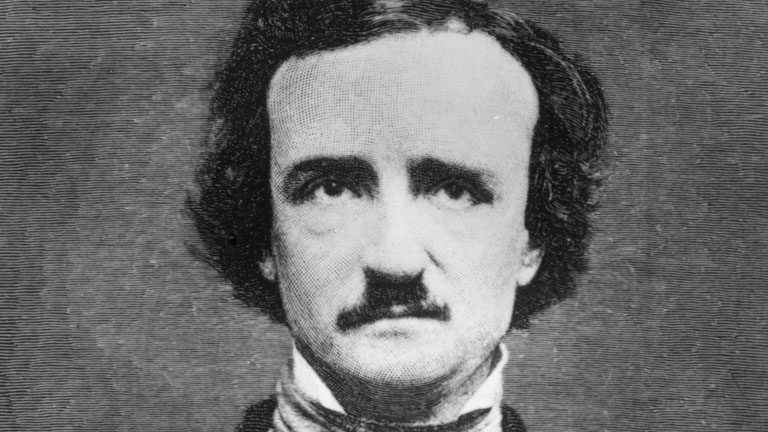

“For decades,” writes the Baltimore Sun, “Edgar Allan Poe’s birthday was marked by a mysterious visitor to his gravesite in Baltimore. Beginning in the 1930s, the ‘Poe Toaster’ placed three roses at the grave every Jan. 19 and opened a bottle of cognac, only to disappear into the night.” The identity of the original “Poe Toaster”—who may have been succeeded by his son—remains a tantalizing mystery. As does the mystery of how Edgar Allan Poe died.

Most of you have probably heard some version of the story. On October 3, 1849, a compositor for the Baltimore Sun, Joseph Walker, found Poe lying in a gutter. The poet had departed Richmond, VA on September 27, bound for Philadelphia “where he was to edit a volume of poetry for Mrs. St. Leon Loud,” the Poe Museum tells us. Instead, he ended up in Baltimore, “semiconscious and dressed in cheap, ill-fitting clothes so unlike Poe’s usual mode of dress that many believe that Poe’s own clothing had been stolen.” He never became lucid enough to explain where he had been or what happened to him: “The father of the detective story has left us with a real-life mystery which Poe scholars, medical professionals, and others have been trying to solve for over 150 years.”

Most people assume that Poe drank himself to death. The rumor was partly spread by Poe’s friend, editor Joseph Snodgrass, whom the poet had asked for in his semi-lucid state. Snodgrass was “a staunch temperance advocate” and had reason to recruit the writer posthumously into his campaign against drink, despite the fact that Poe had been sober for six months prior to his death and had refused alcohol on his deathbed. Poe’s attending physician, John Moran, dismissed the binge drinking theory, but that did not help clear up the mystery. Moran’s “accounts vary so widely,” writes Biography.com, “that they are not generally considered reliable.”

So what happened? Doctors at the University of Maryland Medical Center theorize that Poe may have contracted rabies from one of his own pets—likely a cat. This diagnosis accounts for the delirium and other reported symptoms, though “no one can say conclusively,” admits the Center’s Dr. Michael Benitez, “since there was no autopsy after his death.” As with any mystery, the frustrating lack of evidence has sparked endless speculation. The Poe Museum offers the following list of possible cause of death, with dates and sources, including the rabies and alcohol (both overimbibing and withdrawal) theories:

- Beating (1857) The United States Magazine Vol.II (1857): 268.

- Epilepsy (1875) Scribner’s Monthly Vo1. 10 (1875): 691.

- Dipsomania (1921) Robertson, John W. Edgar A. Poe A Study. Brough, 1921: 134, 379.

- Heart (1926) Allan, Hervey. Israfel. Doubleday, 1926: Chapt. XXVII, 670.

- Toxic Disorder (1970) Studia Philo1ogica Vol. 16 (1970): 41–42.

- Hypoglycemia (1979) Artes Literatus (1979) Vol. 5: 7–19.

- Diabetes (1977) Sinclair, David. Edgar Allan Poe. Roman & Litt1efield, 1977: 151–152.

- Alcohol Dehydrogenase (1984) Arno Karlen. Napo1eon’s Glands. Little Brown, 1984: 92.

- Porphryia (1989) JAMA Feb. 10, 1989: 863–864.

- Delerium Tremens (1992) Meyers, Jeffrey. Edgar A1lan Poe. Charles Scribner, 1992: 255.

- Rabies (1996) Maryland Medical Journal Sept. 1996: 765–769.

- Heart (1997) Scientific Sleuthing Review Summer 1997: 1–4.

- Murder (1998) Walsh, John E., Midnight Dreary. Rutgers Univ. Press, 1998: 119–120.

- Epilepsy (1999) Archives of Neurology June 1999: 646, 740.

- Carbon Monoxide Poisoning (1999) Albert Donnay

The Smithsonian adds to this list the possible causes of brain tumor, heavy metal poisoning, and the flu. They also briefly describe the most popular theory: that Poe died as a result of a practice called “cooping.”

A site called The Medical Bag expands on the cooping theory, a favorite of “the vast majority of Poe biographies.” The term refers to “a practice in the United States during the 19th century by which innocent people were coerced into voting, often several times, for a particular candidate in an election.” Oftentimes, these people were snatched unawares off the streets, “kept in a room, called the coop” and “given alcohol or drugs in order for them to follow orders. If they refused to cooperate, they would be beaten or even killed.” One darkly comic detail: victims were often forced to change clothes and were even “forced to wear wigs, fake beards, and mustaches as disguises so voting officials at polling stations wouldn’t recognize them.”

This theory is highly plausible. Poe was, after all, found “on the street on Election Day,” and “the place where he was found, Ryan’s Fourth Ward Polls, was both a bar and a place for voting.” Add to this the notoriously violent and corrupt nature of Baltimore elections at the time, and you have a scenario in which the author may very well have been kidnapped, drugged, and beaten to death in a voter fraud scheme. Ultimately, however, we will likely never know for certain what killed Edgar Allan Poe. Perhaps the “Poe Toaster” was attempting all those years to get the story from the source as he communed with his dead 19th century friend year after year. But if that mysterious stranger knows the truth, he ain’t talking either.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2015.

Related Content:

7 Tips from Edgar Allan Poe on How to Write Vivid Stories and Poems

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC.