Image via Wikimedia Commons

The site Fast Company published an article that describes the “Complaint Restraint project,” an initiative that aims to create a “positive life by eliminating negative statements.” It’s an admirable goal. Though most of us have a perverse love of wallowing in our misery—a human trait amplified a thousandfold by the internet—complaining rarely makes things any better. As in the Buddha’s parable of the “second arrow,” our griping can make our sufferings doubly painful; as in the parable of the “poisoned arrow,” it can postpone or substitute for the constructive actions we need to take in order to heal or improve our condition.

But it would be a mistake to think that complaining is somehow a recent phenomenon, though we may hear more of it every day, all the time, from every quarter of the globe. The Buddhist arrow stories are, after all, at least a couple thousand years old; lamentation more or less constitutes its own genre in Biblical literature.

Even older still than these religious sources is the first documented customer service complaint, a specific variety of complaining that we might be forgiven for associating mainly with a modern, consumerist age—and one of the few kinds of complaints that can generate positive results.

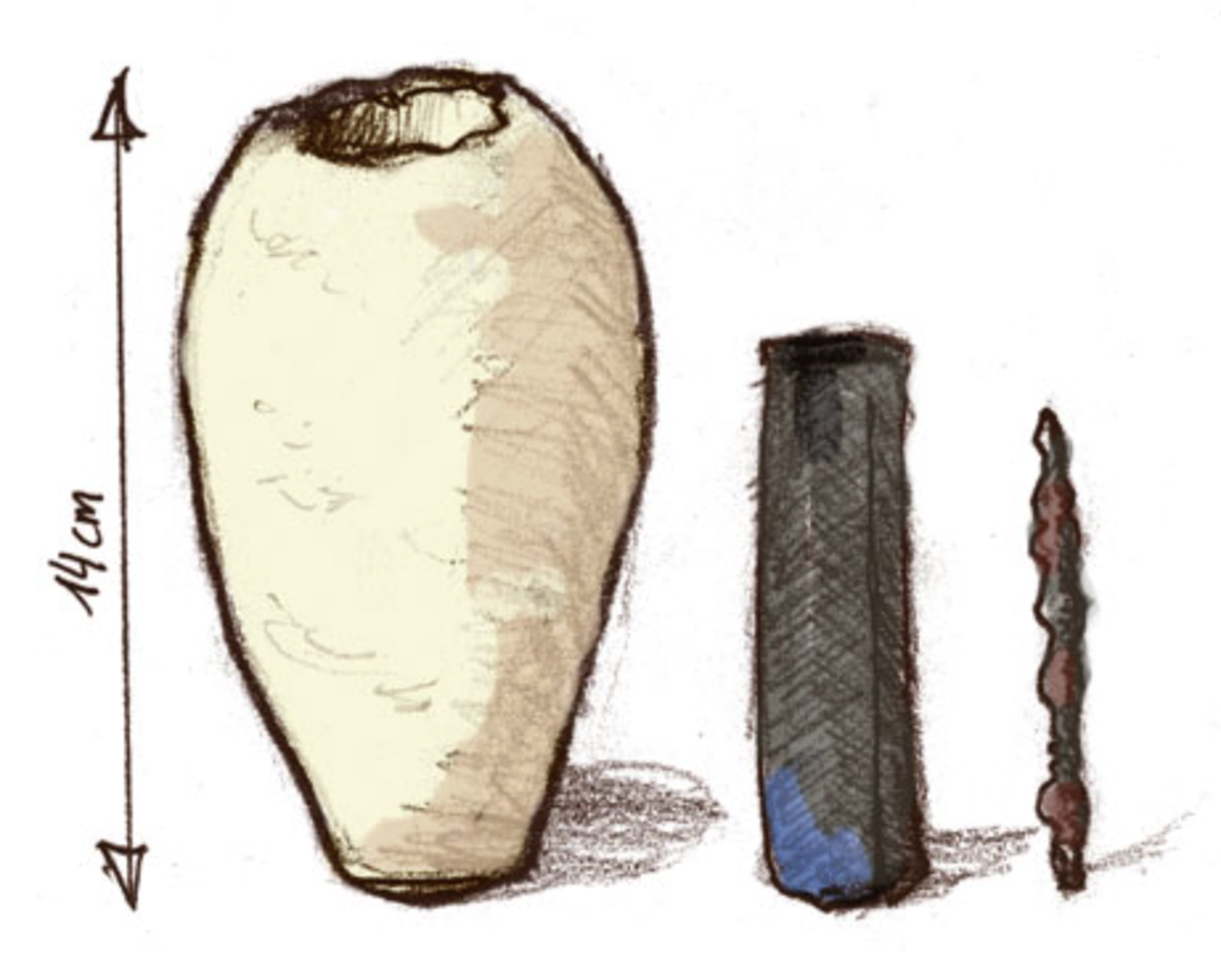

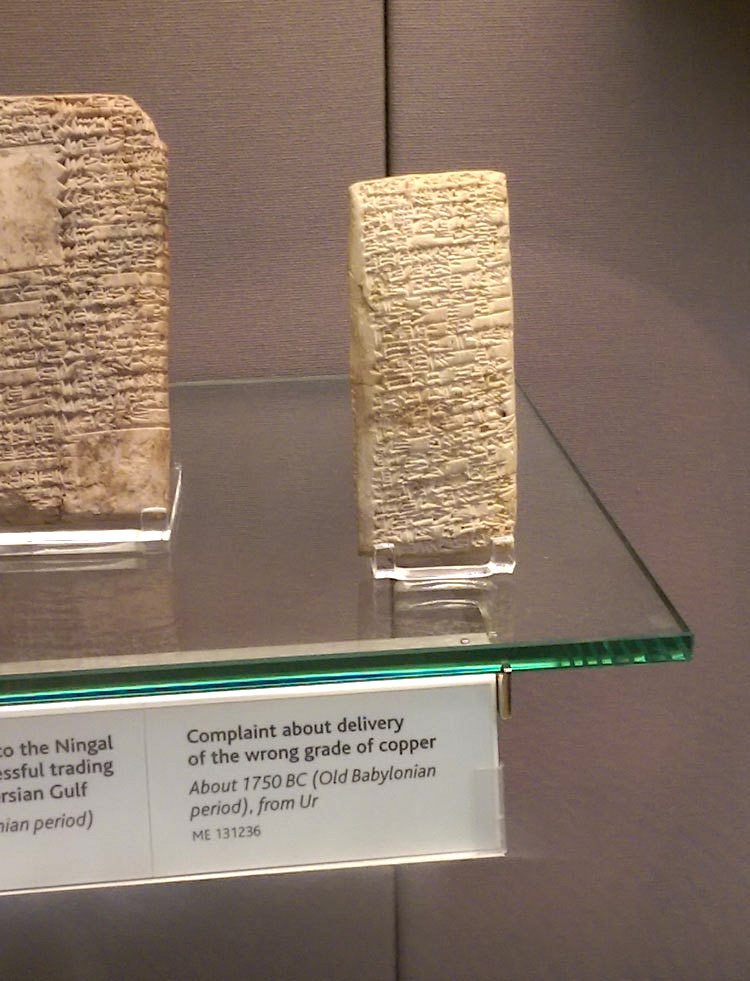

Absent a Yelp app, the ancient Babylonian consumer in this case inscribed his complaint on a clay tablet—which now resides at the British Museum—sometime around 1750 B.C. The irate purchaser here, Nanni, writing to someone named Ea-nasir, received a shipment of copper ore of an inferior grade, after some annoying delay and in a damaged condition. In the translation below from Assyriologist A. Leo Oppenheim, Nanni vents his spleen.

Tell Ea-nasir: Nanni sends the following message:

When you came, you said to me as follows : “I will give Gimil-Sin (when he comes) fine quality copper ingots.” You left then but you did not do what you promised me. You put ingots which were not good before my messenger (Sit-Sin) and said: “If you want to take them, take them; if you do not want to take them, go away!”

What do you take me for, that you treat somebody like me with such contempt? I have sent as messengers gentlemen like ourselves to collect the bag with my money (deposited with you) but you have treated me with contempt by sending them back to me empty-handed several times, and that through enemy territory. Is there anyone among the merchants who trade with Telmun who has treated me in this way? You alone treat my messenger with contempt! On account of that one (trifling) mina of silver which I owe(?) you, you feel free to speak in such a way, while I have given to the palace on your behalf 1,080 pounds of copper, and umi-abum has likewise given 1,080 pounds of copper, apart from what we both have had written on a sealed tablet to be kept in the temple of Samas.

How have you treated me for that copper? You have withheld my money bag from me in enemy territory; it is now up to you to restore (my money) to me in full.

Take cognizance that (from now on) I will not accept here any copper from you that is not of fine quality. I shall (from now on) select and take the ingots individually in my own yard, and I shall exercise against you my right of rejection because you have treated me with contempt.

It does seem that Nanni maybe took this poor service a little too personally. In any case, let’s hope he received some satisfaction for the trouble it must have taken to inscribe this angry message.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2015.

Related Content:

Mark Twain Drafts the Ultimate Letter of Complaint (1905)

Hunter S. Thompson Calls Tech Support, Unleashes a Tirade Full of Fear and Loathing (NSFW)

Behold the Oldest Written Text in the World: The Kish Tablet, Circa 3500 BC

Hear the Oldest Song in the World: A Sumerian Hymn Written 3,400 Years Ago

How to Write in Cuneiform, the Oldest Writing System in the World: A Short Introduction

Hear the Earliest Recorded Customer Complaint Letter: From Ancient Sumeria 1750 BC

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC.