Since its ancient origins as the camera obscura, the photographic camera has always mimicked the human eye, allowing light to enter an aperture, then projecting an image upside down. Renaissance artists relied on the camera obscura to sharpen their own visual perspectives. But it wasn’t until photography—the ability to reproduce the obscura’s images—that the rudimentary artificial eye began evolving the same complex structures we rely on for our own visual acuity: lenses for sharpness, variable apertures, shutter speeds, focus controls…. Only when it began to seem that photography might vie with the other fine arts did the development of camera technology take off. And it moved quickly.

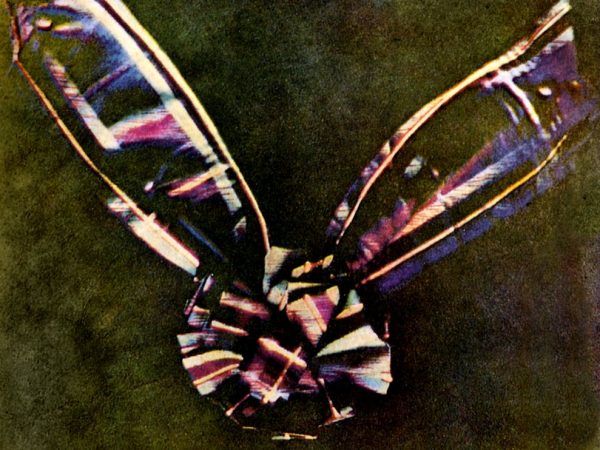

Between the time of the first photograph in 1826 by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce and 1861, photography had advanced sufficiently that physicist James Clerk Maxwell—known for his “Maxwell’s Demon” thought experiment—produced the first color photograph that did not immediately fade or require hand painting (above).

The Scottish scientist chose to take a picture of a tartan ribbon, “created,” writes National Geographic, “by photographing it three times through red, blue, and yellow filters, then recombining the images into one color composite.” Maxwell’s three-color method was intended to mimic the way the eye processes color, based on theories he had elaborated in an 1855 paper.

Maxwell’s many other accomplishments tend to overshadow his color photography (and his poetry!). Nonetheless, the polymath thinker ushered in a revolution in photographic reproduction, almost as an aside. “It’s easy to forget,“ writes BBC picture editor, Phil Coomes, “that not long ago news agencies were transmitting their wire photographs as colour separations, usually cyan, magenta, and yellow—a process that relied on Clerk Maxwell’s discovery. Indeed, even the latest digital camera relies on the separation method to capture light.” And yet, compared to the usual speed of photographic advancement, the process took some time to fully refine.

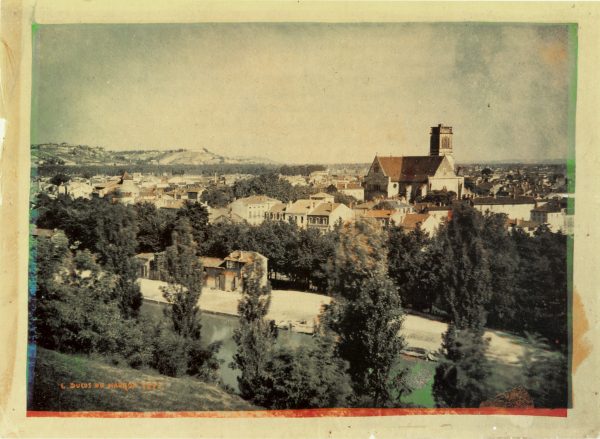

Maxwell created the image with the help of photographer Thomas Sutton, inventor of the single lens reflex camera, but his interest lay principally in its demonstration of his color theory, not its application to photography in general. Sixteen years later, the reproduction of color had not advanced significantly, though a subtractive method allowed more subtlety of light and shade, as you can see in the 1877 example above by Louis Ducos du Hauron. Even so, these nineteenth-century images still cannot compete for vibrancy and lifelikeness with hand-colored photos from the period. Despite appearing artificial, hand-tinted images like these of 1860s Samurai Japan brought a startling immediacy to their subjects in a way that early color photography did not.

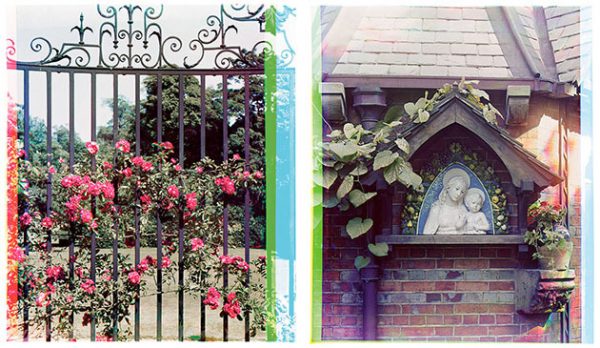

It wasn’t until the early 20th century—with the development of color processes by Gabriel Lippman and the Sanger Shepherd company—that color came into its own. Leo Tolstoy appeared early in the century in brilliant full color photos. Paris came alive in color images during WWI. And Sarah Angelina Acland, a pioneering English photographer, took the image above in 1900 using the Sanger Shepherd method. That process—patented, marketed, and sold—thoroughly improved upon Maxwell’s results, but its basic operation was nearly the same: three images, red, green, and blue, combined into one.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2016.

Related Content:

The First Photograph Ever Taken (1826)

Hand-Colored 1860s Photographs Reveal the Last Days of Samurai Japan

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness