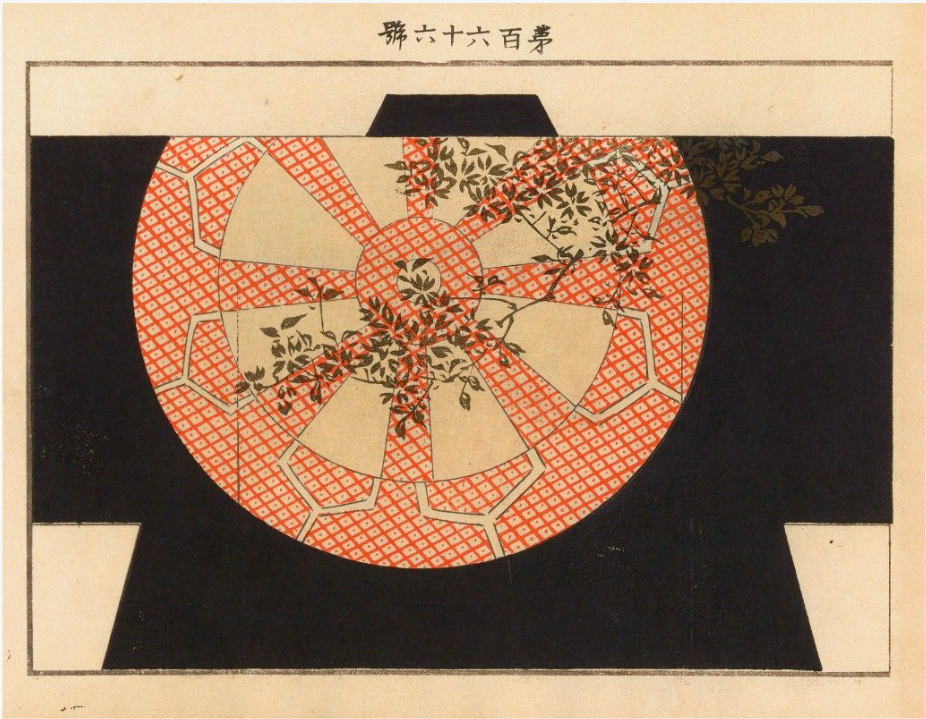

Visitors to Japan can’t help but be struck by the beauty of its temples, its scenic views, its zen gardens, its manhole covers…

You read that right.

What started as a scheme to get taxpayers on board with pricey rural sewer projects in the 1980s has grown into a countrywide tourist attraction and a matter of civic pride.

Each municipality boasts its own unique manhole cover designs, inspired by specific regional elements.

A community might opt to rep its local floral or fauna, a famous local landmark or festival, an historic event or bit of folklore.

Matsumoto City highlights one of its popular folk craft souvenirs, the colorful silk temari balls that once served as toys for female children and bridal gifts.

Nagoya touts the purity of its water with a water strider — an insect that requires the most pristine conditions to survive.

Hiroshima pays tribute to its baseball team.

Osaka offers a view of its castle surrounded by cherry blossoms.

The proximity of the Sanrio Puroland theme park allows Tama City to lay claim to Hello Kitty and Pokémon-themed lids have sprung up like mushrooms from Tokyo to Okinawa.

Most of Japan’s 15 million artistic manhole covers are monochromatic steel which makes spotting one of the vibrantly colored models even more exciting.

In the fifty some years since their introduction, an entire subculture has emerged. Veteran enthusiast Shoji Morimoto coined the term “manholer” to describe hobbyists participating in this “treasure hunt for adults.”

Remo Camerota documents his obsession in Drainspotting: Japanese Manhole Covers and American traveler Carrie McNinch shares the joy of stumbling across previously unspotted ones in her autobiographical comic series You Don’t Get There From Here.

The ongoing popularity of this officially sanctioned street art is evidenced by the Japanese Society of Manhole Lovers, an annual manhole summit, and tons of collectible trading cards.

Explore a crowdsourced gallery of Japanese manhole covers here.

Related Content

Discover Edo, the Historic Green/Sustainable City of Japan

The Making of Japanese Handmade Paper: A Short Film Documents an 800-Year-Old Tradition

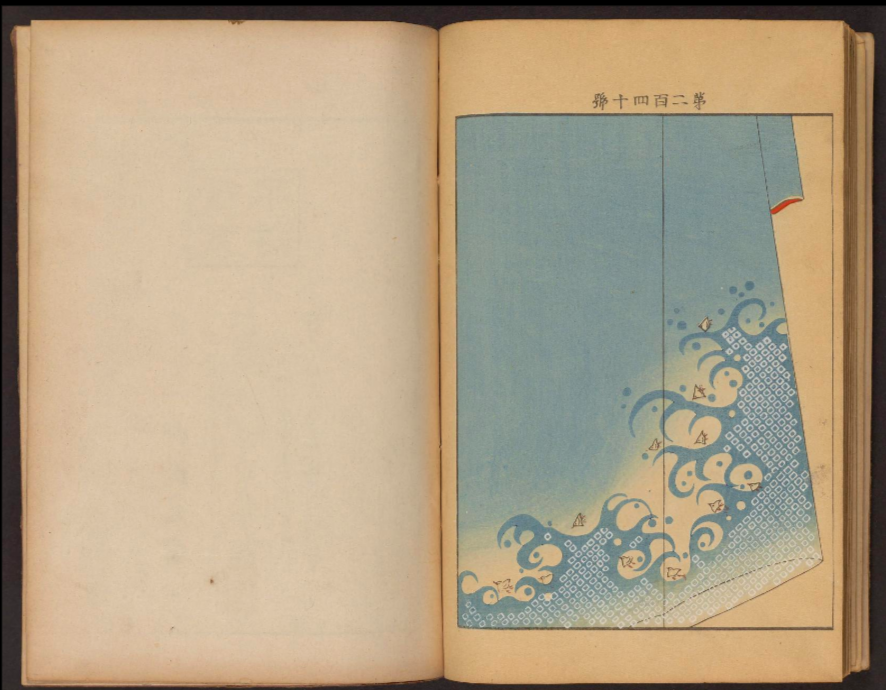

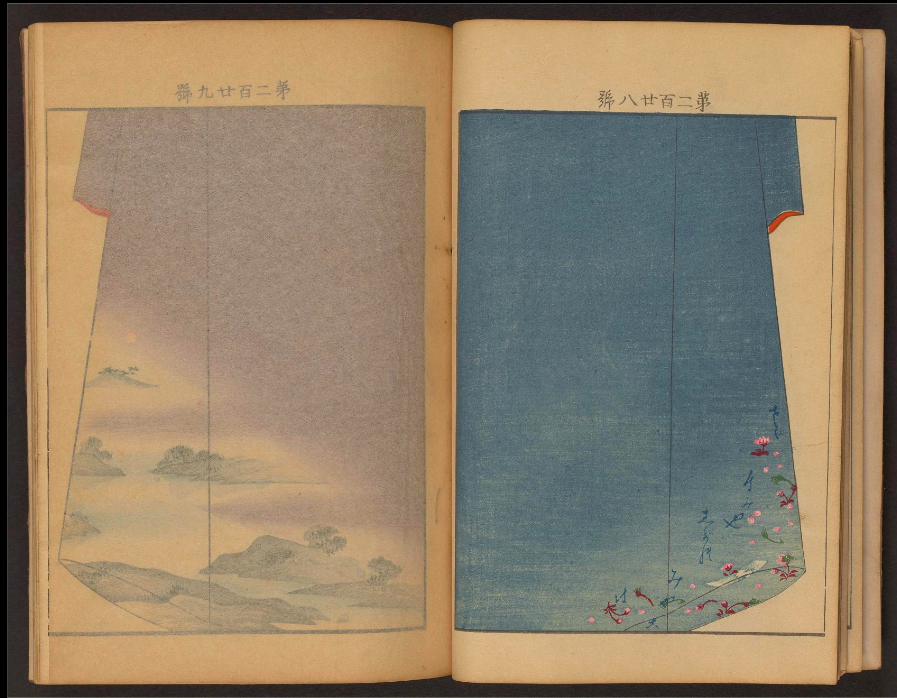

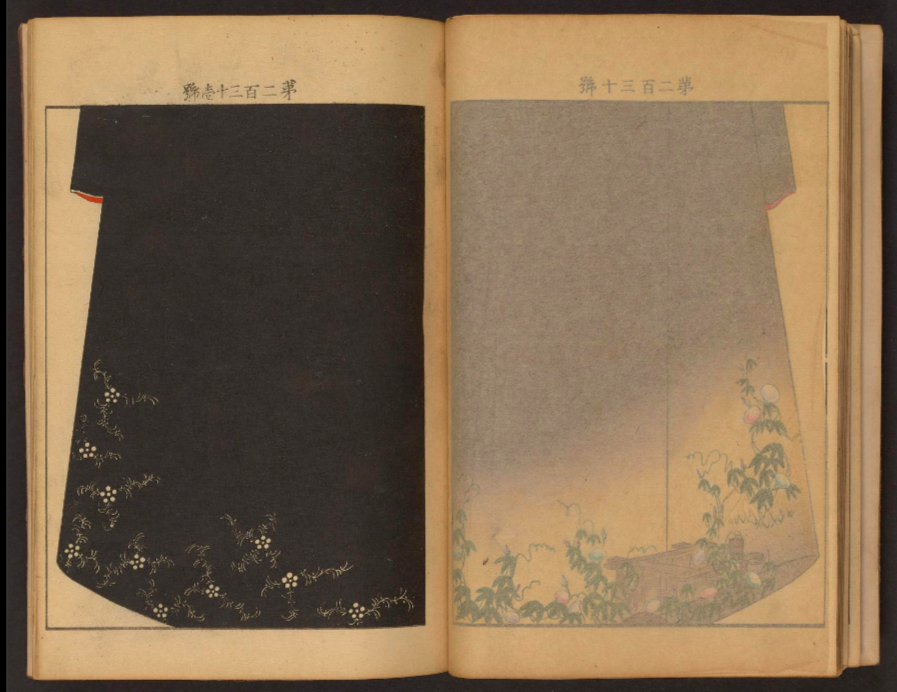

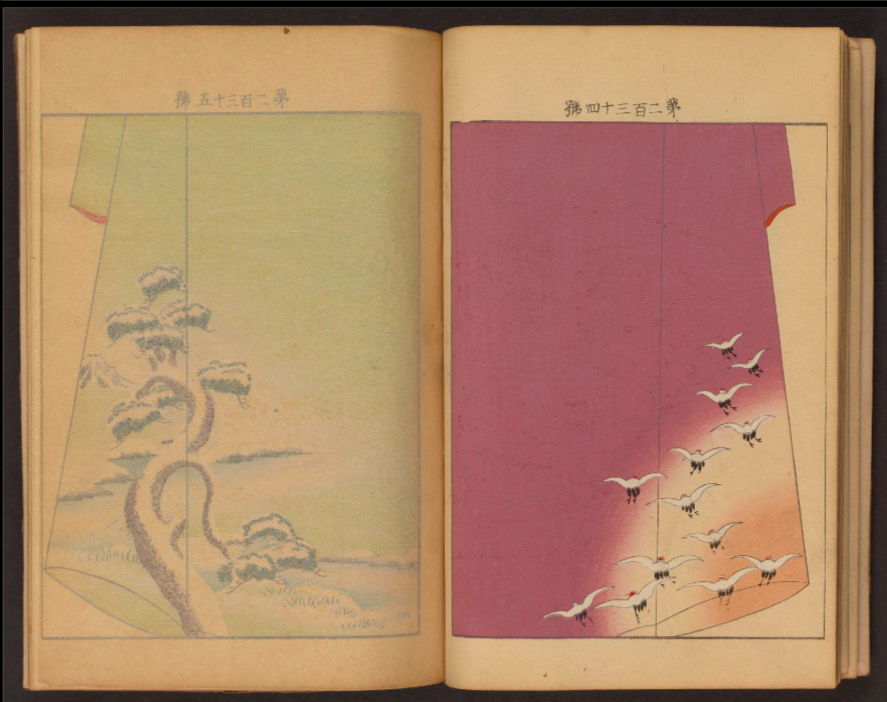

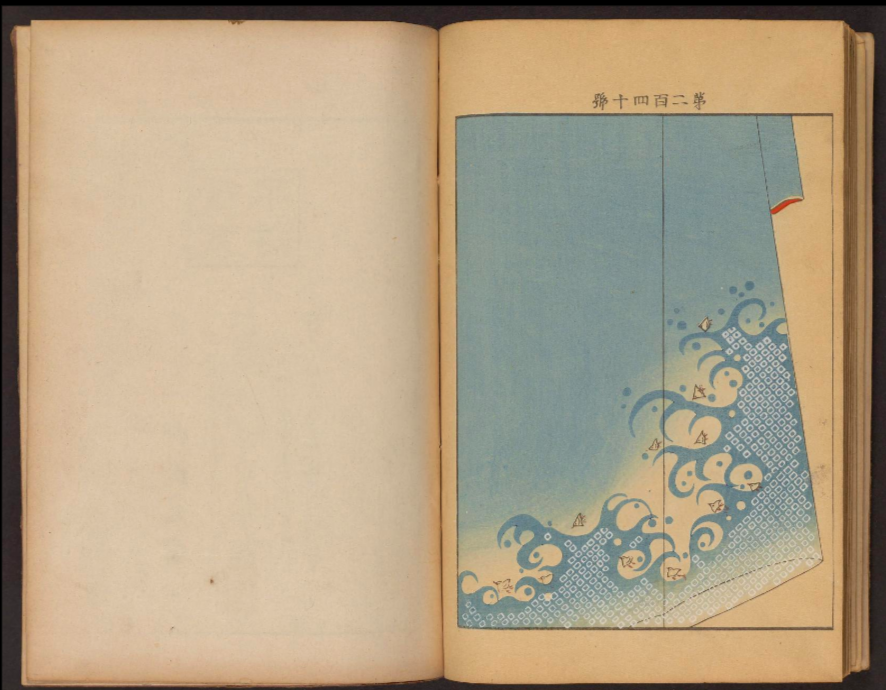

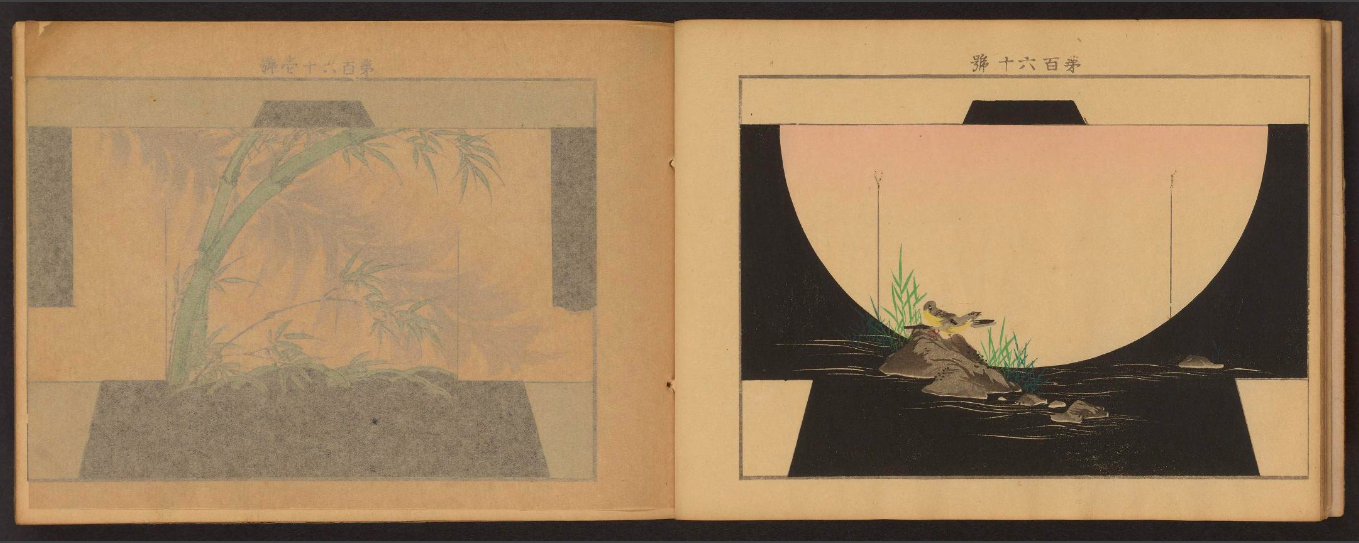

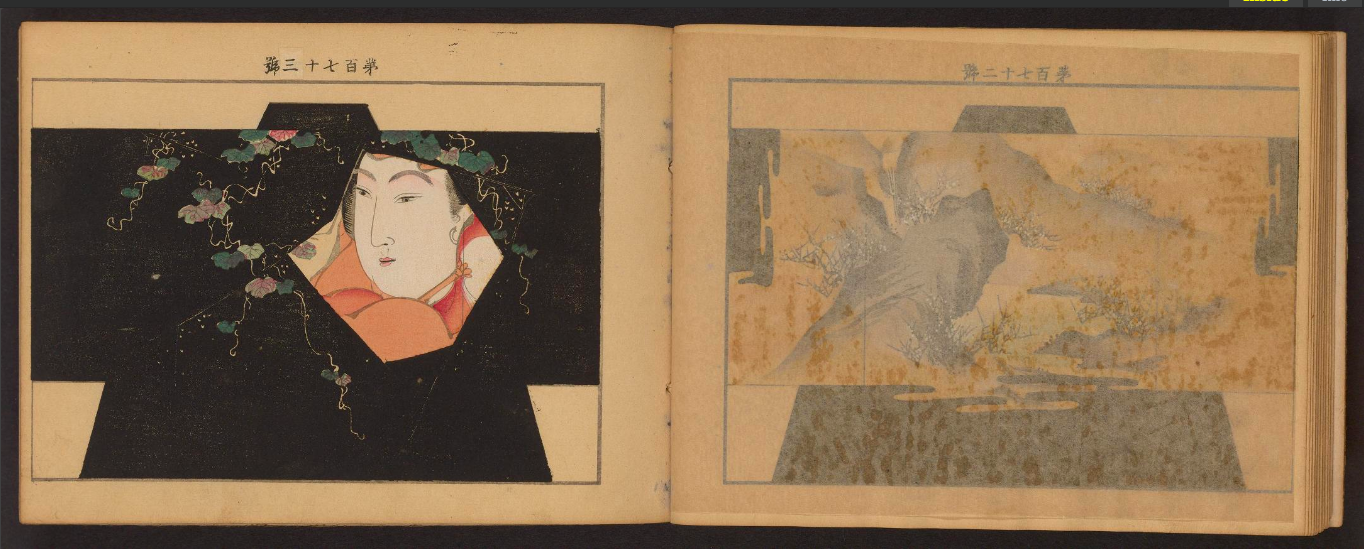

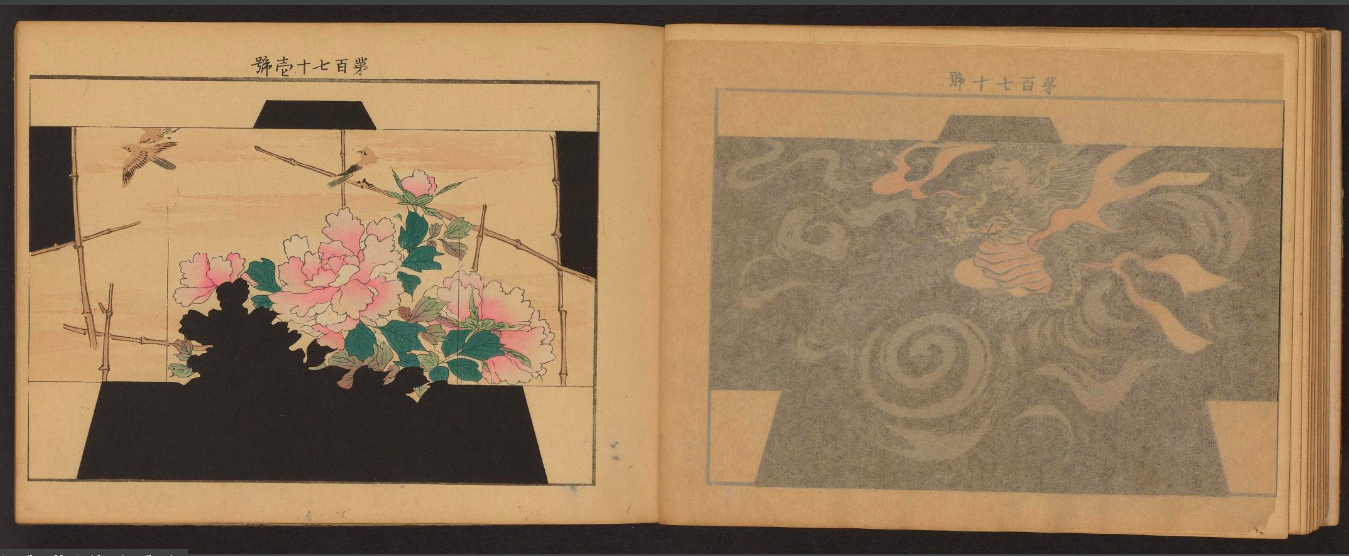

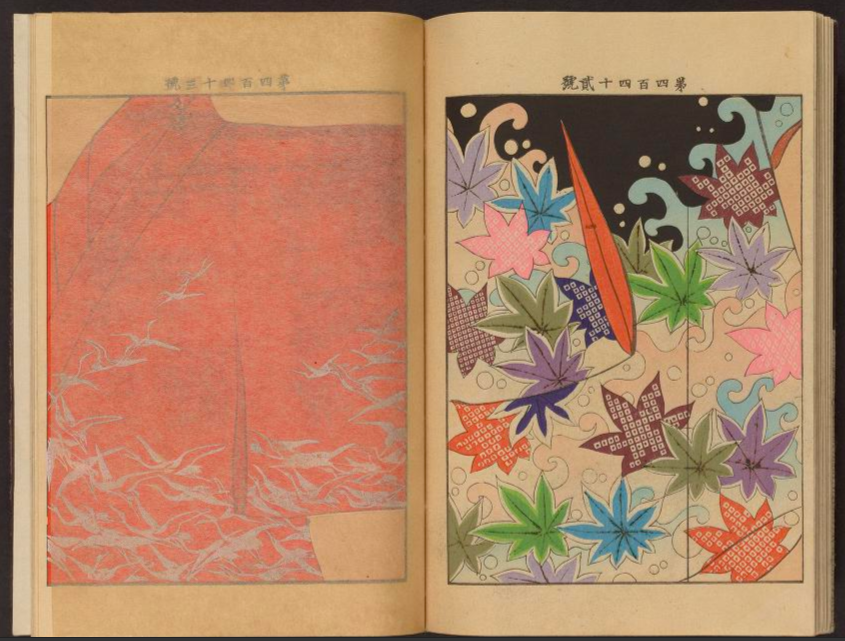

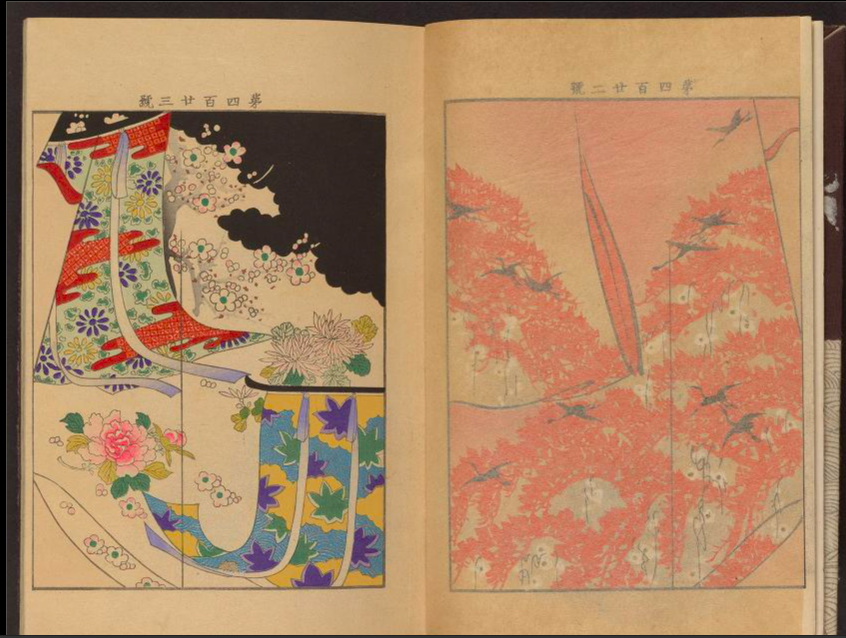

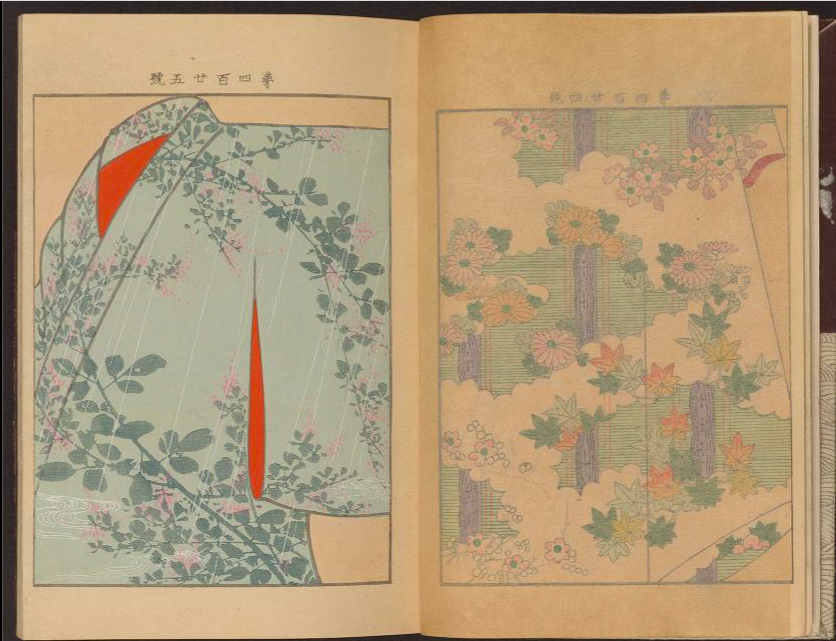

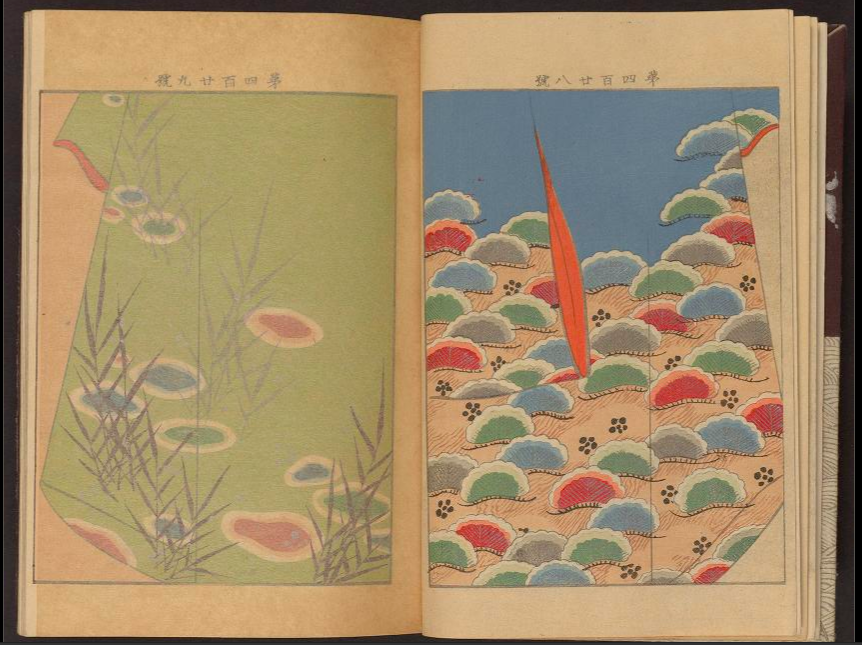

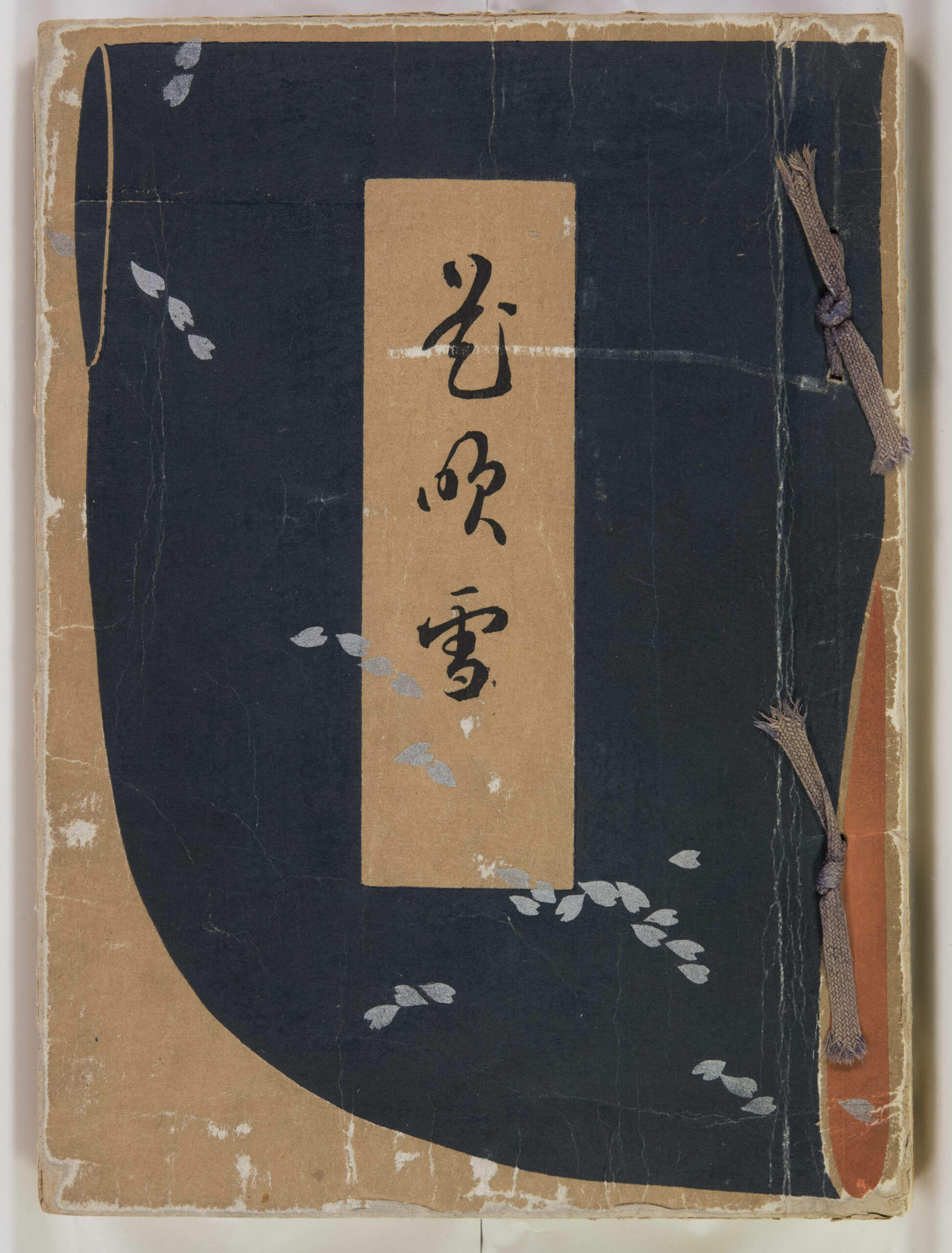

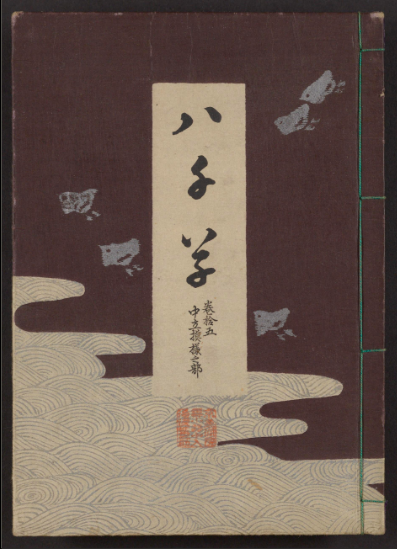

Download Classic Japanese Wave and Ripple Designs: A Go-to Guide for Japanese Artists from 1903

Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of The East Village Inky zine and nine books, including, most recently Creative, Not Famous. Follow her @Ayun-Halliday