The Tarot has long been a tool of charlatans. But it has also long been embraced by brilliant, unconventional thinkers, many of whom themselves have a touch of the charlatan about them (and who would just as likely admit it with a smile). William Butler Yeats was a fan, as is visionary Chilean filmmaker, artist, writer, and psychonaut Alejandro Jodorowsky, who has recorded his own Youtube series explaining his take on this classic mode of divination. With its archetypal symbolism, the Tarot’s appeal to artists should be obvious. Most of them, like Jodorowsky, find far more interesting uses for it than fortune-telling. “You must not talk about the future,” Jodorowsky tells us in his series, “the future is a con. The tarot is a language that talks about the present.”

What might another visionary artist, Salvador Dalí, think of Jodorowsky’s Tarot interpretations? We’ll never know, but I suspect he would find them enchanting. Not only do the two seem like kindred spirits, but Dalí devoted some part of his life to the Tarot, designing his own deck in the 70s.

Initially, the project arrived as a commission from producer Albert Broccoli for the James Bond film Live and Let Die. “Likely inspired by his wife Gala, who nurtured his interest in mysticism,” writes Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art, “Dalí eagerly got to work, and continued the project of his own accord when the contractual deal fell through.”

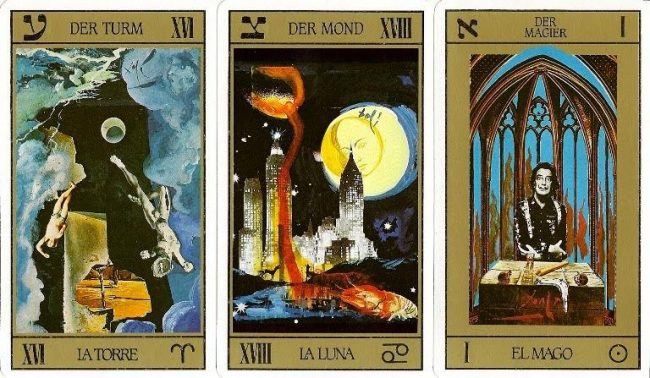

It was just around this time that the Tarot saw a massive resurgence in popularity. The occult interests of the 60s counterculture were mainstreamed in the 70s thanks to books like Stuart Kaplan’s Tarot Cards for Fun and Fortune Telling. But while Dalí had channeled the vivid psychedelia of the age in an earlier illustration project, 1969’s Alice and Wonderland, his Tarot deck, writes Lisa Rainwater at Galo magazine, “actually shows reserve. Yes, reserve—as if his reverence for the tarot nearly humbles him.” His knack for “fanatical self-promotion” does get the better of him eventually: he chooses his own face to represent the Magician (above).

Overall, the deck combines the eclectic origins of occult practices with Dalí’s own unmistakable sensibility. Dalí’s Tarot is “a pastiche of old-world art, surrealism, kitsch, Christian iconography and Greek and Roman sculpture. Many of his recurring motifs such as the rose, the fly and the bull’s head are found throughout the deck.” First published in a limited edition in 1984—and reissued since in editions by TASCHEN and in book form by other publishers—the deck included an introductory booklet that reads, in Spanish, English, and French:

The Wizard (Arcanum I), Salvador Dalí, has transformed with his exceptional art and his marvelous talent the 78 golden plates of ‘The fabulous book of Thot’ into as many artistic marvels, each one of them duly signed by the hand of this unmatchable, internally famous painter … such an extraordinary artistic creation does not detract, in any way, from the Tarot’s close symbolism. On the contrary, it enhances with its captivating beauty, the Tarot’s esoteric and plastic meaning.

See a preview video of the full Dalí deck above, purchase a limited edition set here, or a much more affordable version here.

NOTE: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2016.

Related Content:

Philip K. Dick Tarot Cards: A Tarot Deck Modeled After the Visionary Sci-Fi Writer’s Inner World

Alejandro Jodorowsky Explains How Tarot Cards Can Give You Creative Inspiration

Behold the Sola-Busca Tarot Deck, the Earliest Complete Set of Tarot Cards (1490)

The Pulp Tarot: A New Tarot Deck Inspired by Midcentury Pulp Illustrations

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness