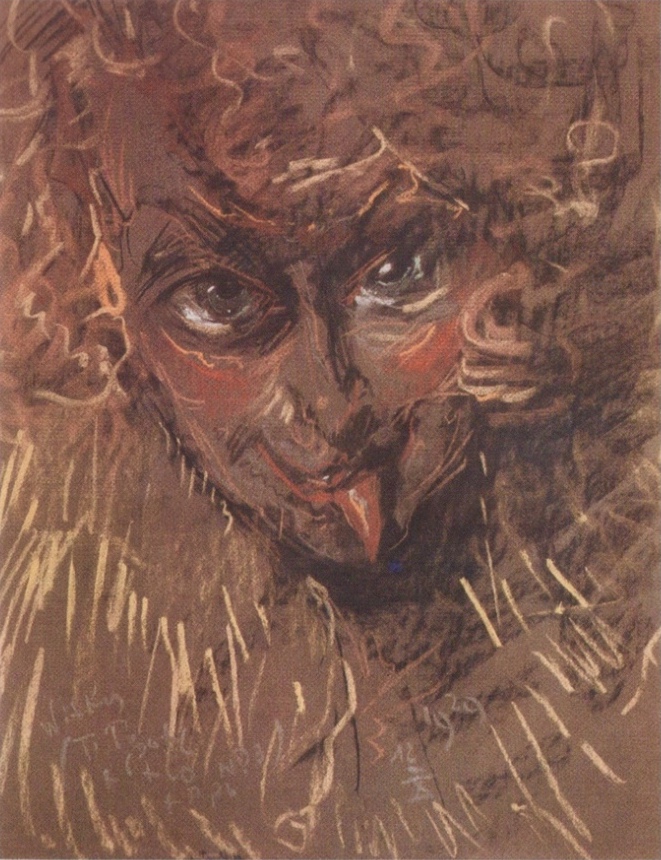

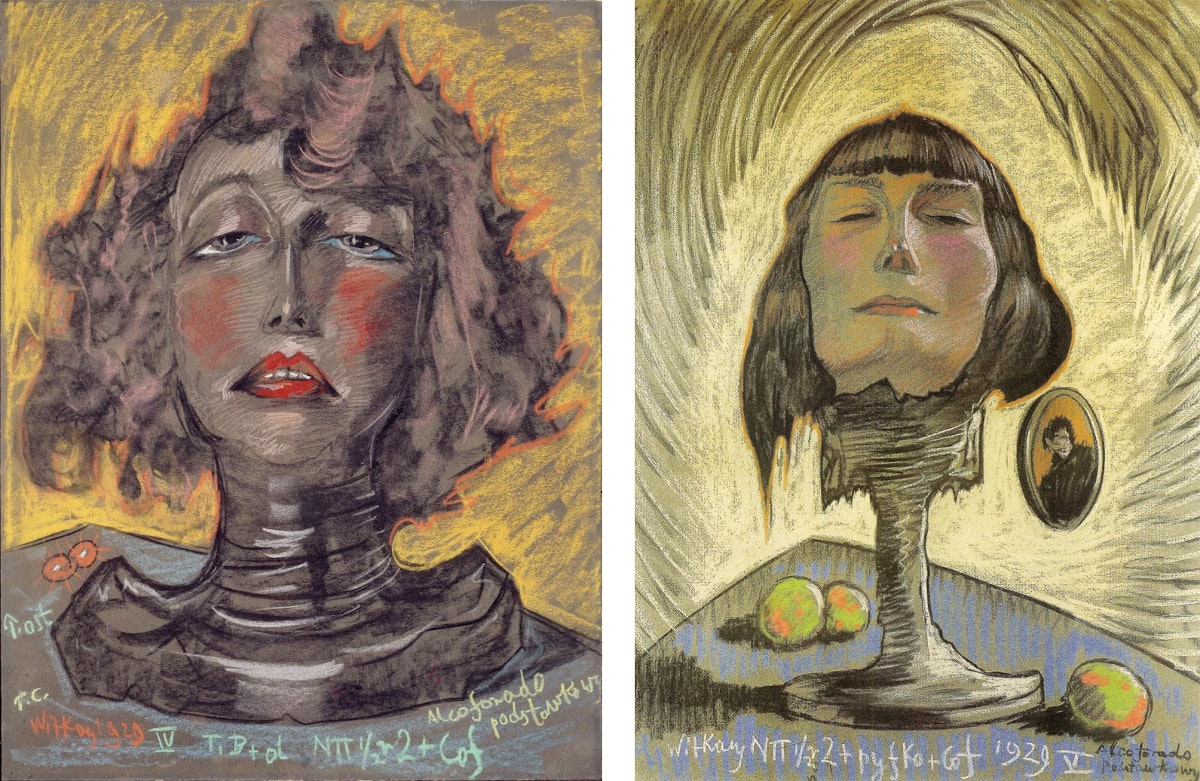

The Scream is not screaming. “One of the famous in the images of art,” Edvard Munch’s most widely seen painting “has become, for us, a universal symbol of angst and anxiety.” Munch painted it in 1893, when “Europe was at the birth of the modern era, and the image reflects the anxieties that troubled the world.” However many fin-de-siècle Europeans felt like screaming for one reason or another, the central figure of The Scream isn’t one of them: “rather, it is holding its hands over its ears, to block out the scream.” So gallerist and Youtuber James Payne reveals on the latest episode of his series Great Art Explained, which doesn’t just examine Munch’s iconic work of art, but places it in the context of his career and his time.

During most of Munch’s life, “European cities were going through truly exceptional changes. Industrialization and economic shifts brought fear, obsessions, diseases, political unrest, and radicalism. Questions were being raised about society, and the changing role of man within it: about our psyche, our social responsibilities, and most radical of all, about the existence of God.” It was hardly the most suitable time or place for the mentally troubled, but then, Munch seems to have possessed more psychological fortitude than he let the public know. A savvy self-promoter, he understood the value of living like someone whose terrible perceptions keep him on the brink of total breakdown.

But then, Munch never did have it easy. “His mother and his sister both died of tuberculosis. His father and grandfather suffered from depression, and another sister, Laura, from pneumonia. His only brother would later die of pneumonia.” He found solace in art, a pursuit strongly opposed by his religious father, and eventually joined the bohemian world, a milieu that encouraged him to let his inner world shape his aesthetic. Drawing inspiration from the French Impressionists and the drama of August Strindberg, Munch eventually found his way to starting a cycle of paintings called The Frieze of Life.

It was during his work on The Frieze of Life that, according to a diary entry of January 22nd, 1892, Munch found himself walking along a fjord. “I felt tired and ill. I stopped and looked out over the fjord — the sun was setting, and the clouds turning blood red. I sensed a scream passing through nature; it seemed to me that I heard the scream. I painted this picture, painted the clouds as actual blood. The color shrieked.” The fjord was on the way back from the asylum to which his beloved younger sister had recently been confined; Payne imagines that her “screams of terror must have haunted him as he walked away.” From these grim origins, The Scream emerged to become an oft-referenced and highly relatable image — even to those who see in it nothing more than their own frustration at receiving too much e‑mail.

Related content:

How Edvard Munch Signaled His Bohemian Rebellion with Cigarettes (1895): A Video Essay

Explore 7,600 Works of Art by Edvard Munch: They’re Now Digitized and Free Online

The Life & Work of Edvard Munch, Explored by Patti Smith and Charlotte Gainsbourg

Edvard Munch’s Famous Painting “The Scream” Animated to Pink Floyd’s Primal Music

The Edvard Munch Scream Action Figure

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.