“One of the biggest considerations when traveling to Japan is its inscrutable language,” writes Designboom’s Juliana Neira. But then, one might also consider making that language more scrutable — and making one’s experience in Japan much richer — by learning some of it. Kanji, the Chinese characters used in the written Japanese language, may at first look like small, often bewilderingly complex pictures, and many assume they visually evoke the meanings they express. In fact, to use the linguistic terms, they’re not pictograms, representations of thoughts or ideas, but logograms, representations of words or parts of words.

Resemble miniature works of art though they often do, kanji aren’t entirely unsystematic. This helps beginning learners get a handle on the first and most essential characters of the thousands they’ll eventually need to know.

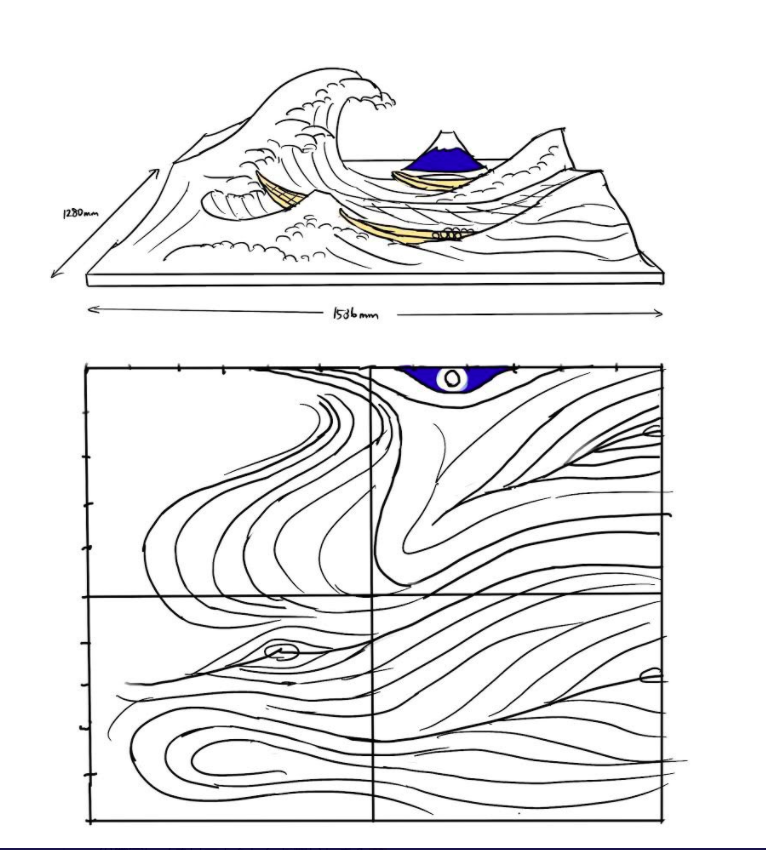

So does the fact that some of them, in origin, really are pictographic — that is, they look like the meaning of the word they represent — or at least pictographic enough to make them teachable through images. The Japanese word for “mountain,” to cite an elementary example, is 山; “river” is 川; “tree” is 木. Alas, most of us who enjoy the 山, 川, and 木 of Japan — to say nothing of the 書店 and 喫茶店 in its cities — haven’t been able to visit them at all in this past pandemic year.

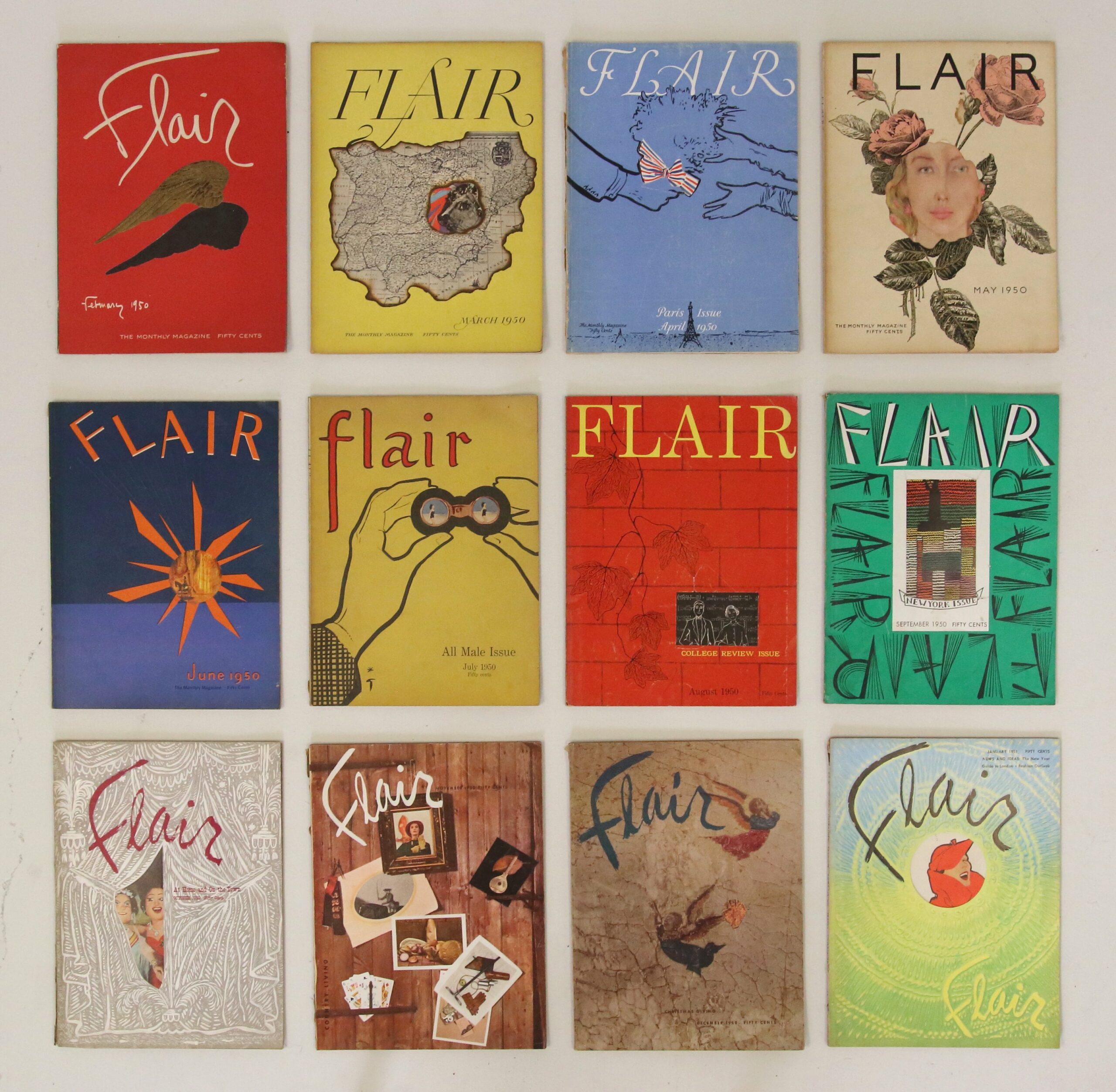

“After experiencing years of tourism growth, tourists to Japan are down over 95% due to the pandemic,” writes Spoon & Tamago’s Johnny Waldman. “Graphic designer Kenya Hara and his firm Nippon Design Center have self-initiated a project to release over 250 pictograms — free for anyone to use — in support of tourism in Japan from a visual design perspective.” Collectively bannered the Experience Japan Pictograms, these clear and evocative icons represent a wide range of the places and activities one can enjoy in the Land of the Rising Sun: skiing and surfing, calligraphy and open-air hot-spring bathing, Ginza and Asakusa, Tokyo’s Skytree and Osaka’s Tsūtenkaku Tower.

The Experience Japan Pictograms hardly fail to include the glories of Japanese cuisine — sushi, tempura, soba, and even the Japanified hanbāgā — which piques so many foreigners’ interest in Japan to begin with. Click on any of them and you’ll see a brief cultural and historical explanation of the item, activity, place, or concept in question, along with the relevant Japanese term (in kanji where applicable) and its pronunciation. You can also download them in the color scheme of your choice and use them for any purposes you like, including commercial ones. The more widely adopted they are, the more convenient Japanese tourism will become for those who don’t read Japanese. Those who do can hardly deny the pleasure of having another Japanese language to learn — and a truly pictographic one at that.

via Spoon & Tamago

Related Content:

Vintage 1930s Japanese Posters Artistically Market the Wonders of Travel

The Hobo Code: An Introduction to the Hieroglyphic Language of Early 1900s Train-Hoppers

Google Makes Available 750 Icons for Designers & Developers: All Open Source

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.