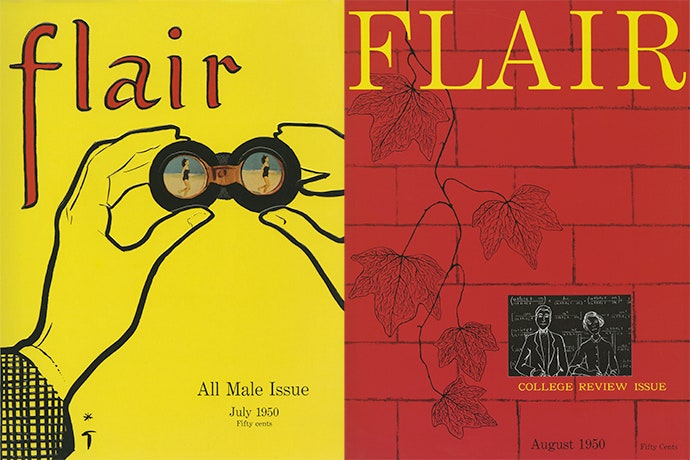

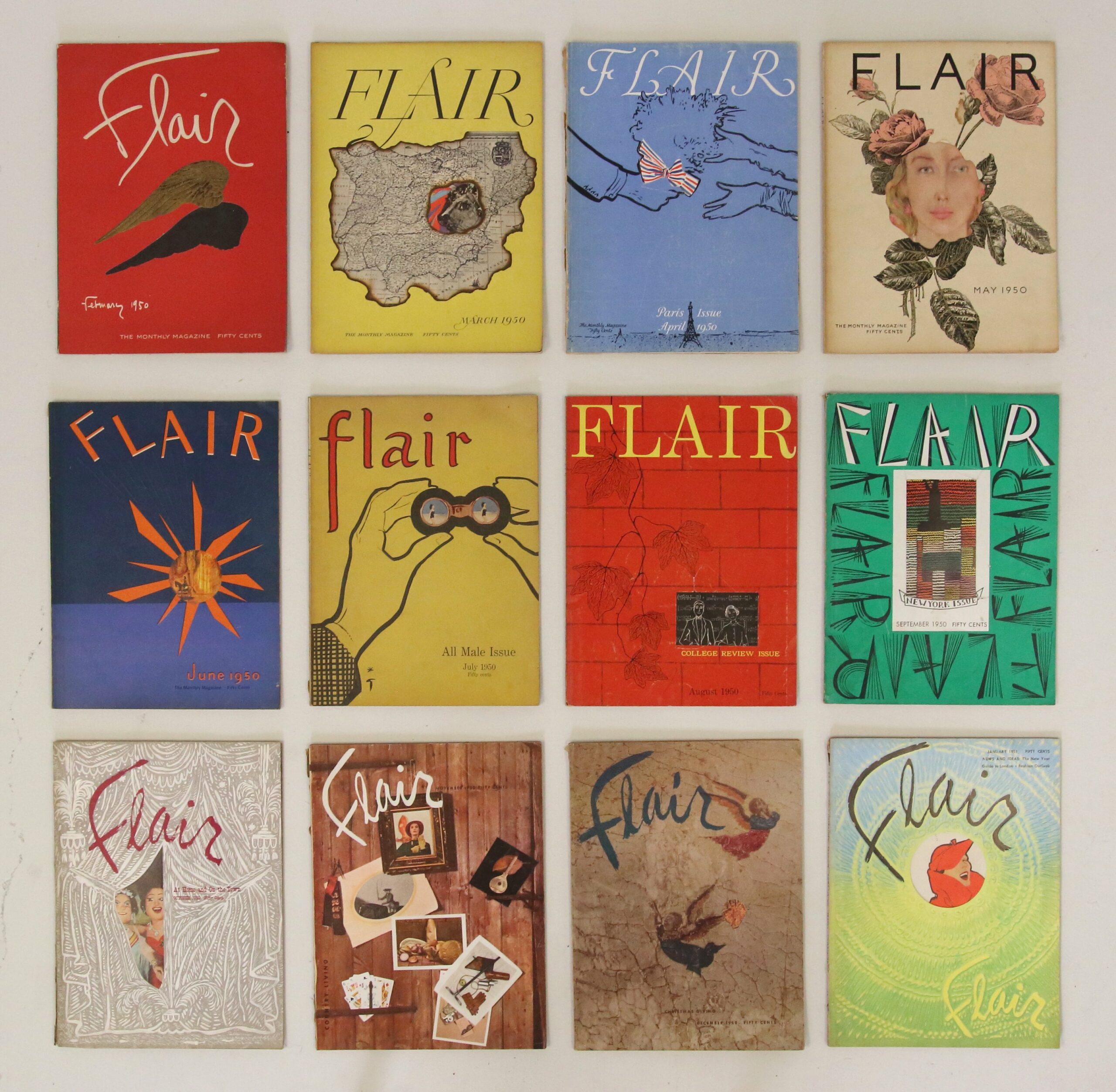

All magazines are their editors, but Flair was more its editor than any magazine had been before — or, for that matter, than any magazine has been since. Though she came to the end of her long life in England, a country to which she had expatriated with her fourth husband, a Briton, Fleur Cowles was as American a cultural figure as they come. Born Florence Freidman in 1908, she had performed on herself an unknowable number of Gatsbyesque acts of reinvention by 1950, when she found herself in a position to launch Flair. Her taste in husbands helped, married as she then was to Gardner “Mike” Cowles Jr., publisher of Look, a popular photo journal that Fleur had helped to lift from its lowbrow origins and make respectable among that all-powerful consumer demographic, postwar American women.

The success of the reinvented Look “allowed Cowles to ask her husband for what she really wanted: the capital to start her own publication, which she called ‘a class magazine,’ ” writes Eye on Design’s Rachel Syme. “She was tired of spreads about the best linoleum; she wanted to do an entire issue on Paris, or hire Ernest Hemingway to write a travel essay, or commission Colette to gossip about her love affairs.”

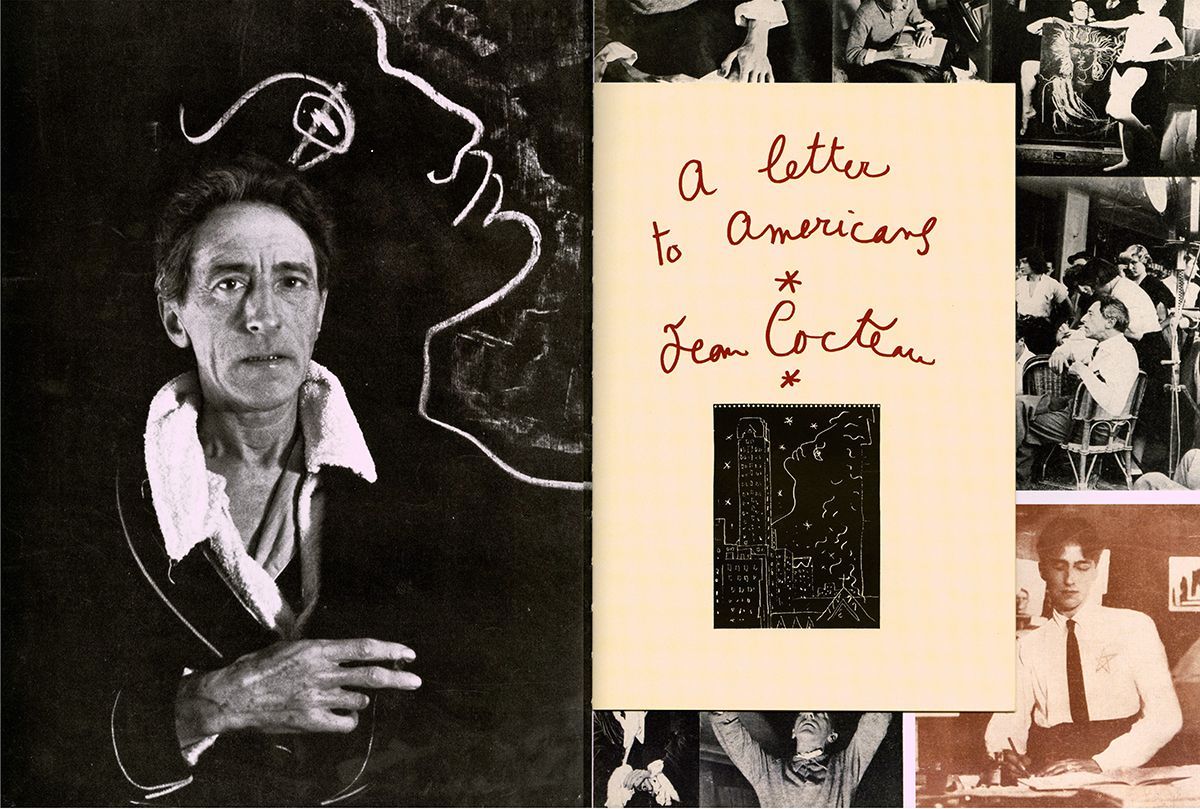

During Flair’s run she did all that and more, with a roster of contributors also including Salvador Dalí, Simone de Beauvoir, W. H. Auden, Gloria Swanson, Winston Churchill, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Jean Cocteau. In Flair’s debut issue, published in February 1950, “an article on the 28-year-old Lucian Freud came liberally accompanied with reproductions of his art—the first ever to appear in America.”

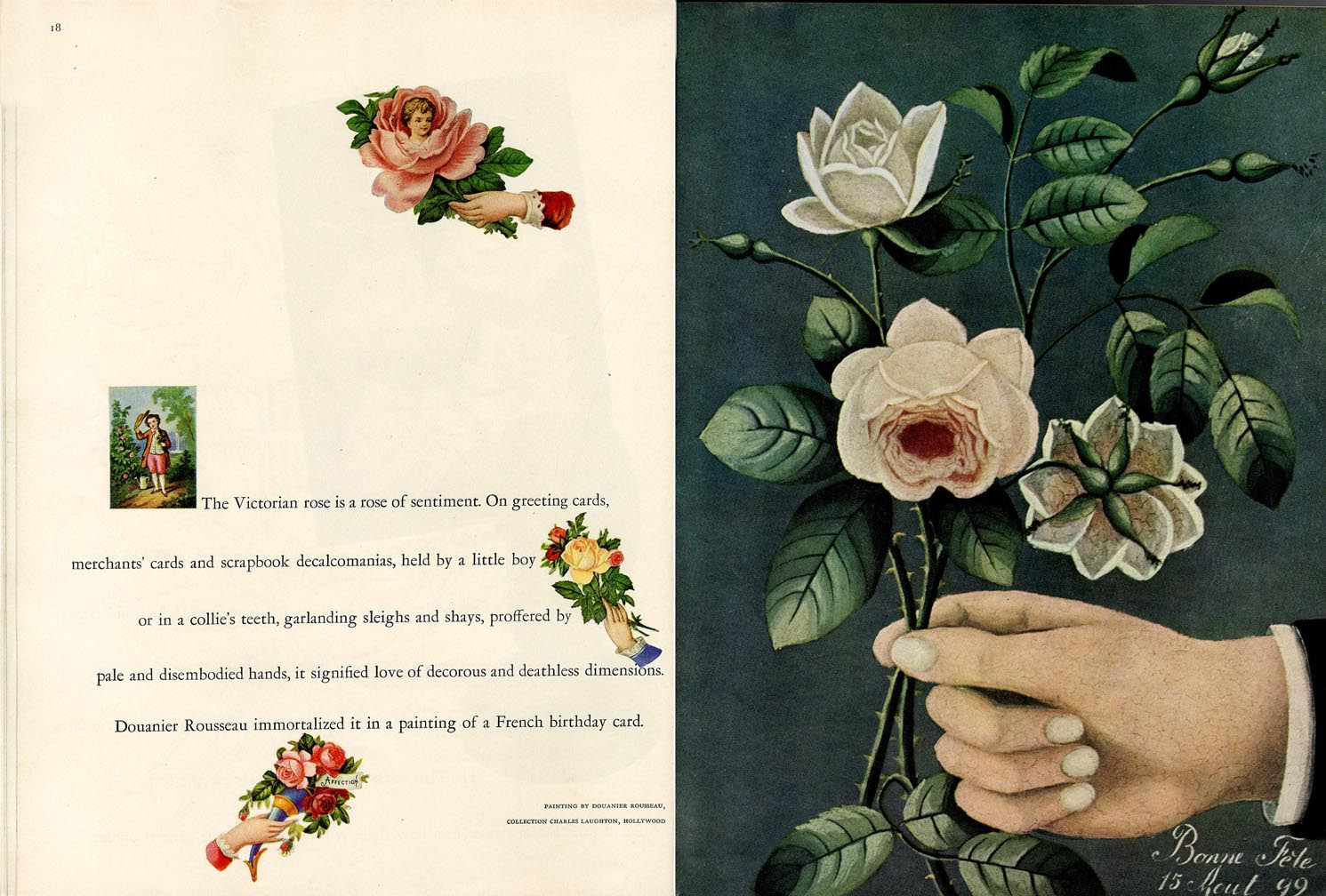

So writes Vanity Fair’s Amy Fine Collins in a profile of Clowes. “Angus Wilson and Tennessee Williams contributed short stories, Wilson’s printed on paper textured to resemble slubbed silk.” What’s more, “The Duke and Duchess of Windsor opened their home to Flair’s readers, treating them to their recondite and entertaining tips. A more futuristic approach to living was set forth in a two-page spread on Richard Kelly’s lighting design for Philip Johnson’s glass house in Connecticut.” Feature though it may have the work of an astonishingly varied group of luminaries — pulled in by Cowles’ vast and deliberately woven social net — Flair is even more respected today for each issue’s lavish, elaborate, and distinctive design.

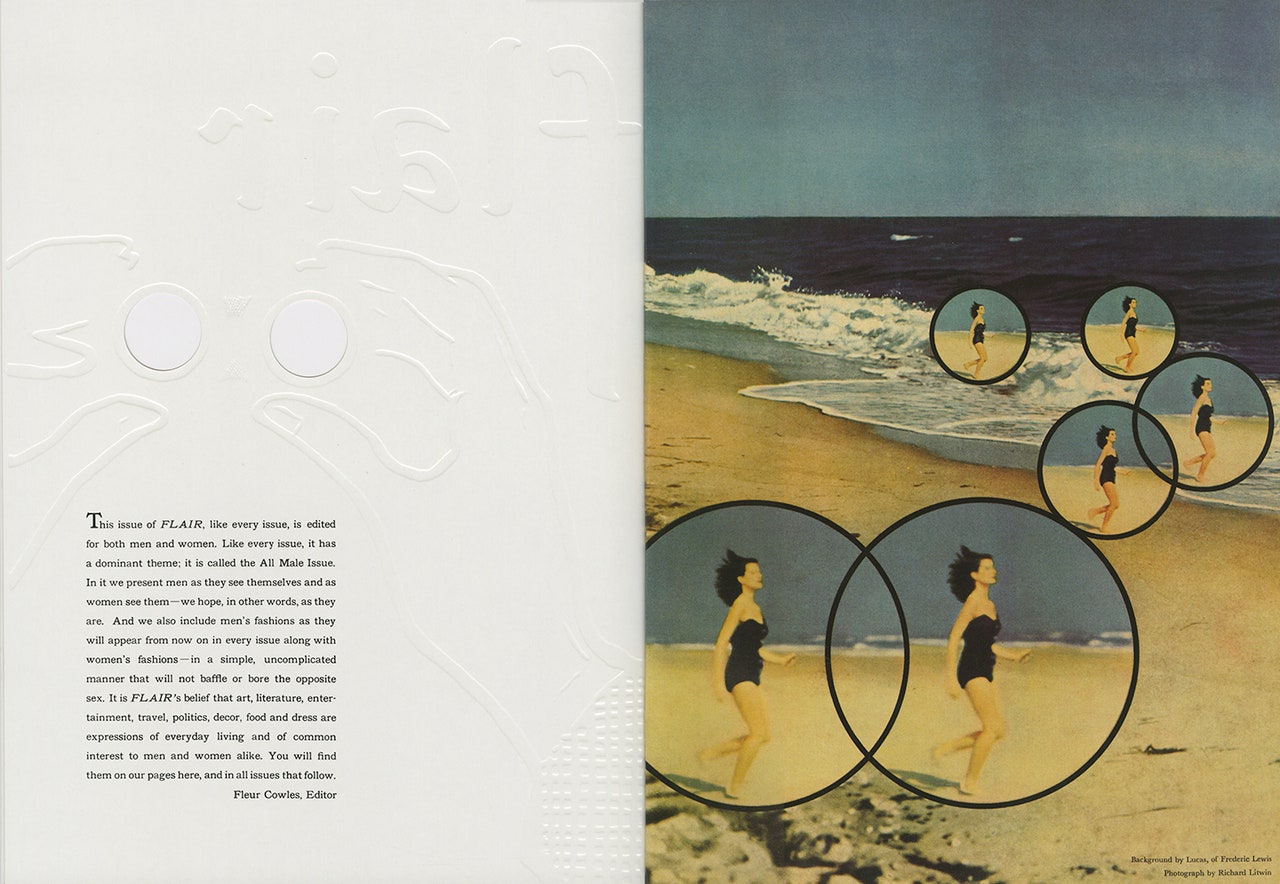

“If a feature would be better in dimension than on flat pages, why not fold half-pages inside double-page spreads?” asks Cowles in her memoirs, quoted in Print magazine. “Why not bind it as ‘a little book’ … giving it a special focus? If a feature was better ‘translated’ on textured paper, why use shiny paper?” And “if a painting was good enough to frame, why not print it on properly heavy stock? Why not bind little accordion folders into each issue to give the feeling of something more personal to the content?” One reason is the $2.5 million (1950 dollars) that Mike Cowles estimated Flair to have cost in the year it ran before he pulled its plug.

But then, by the early 1970s even the highly profitable Look had to fold — and of the two magazines, only one has become ever more sought-after, has books published in its tribute, and still inspires designers today. To take a closer look at the magazine, see The Best of Flair, a compilation of the magazine’s best content as chosen by Fleur Cowles herself. (See a video preview of the book above.)

Related Content:

Vogue Editor-in-Chief Anna Wintour Teaches a Course on Creativity & Leadership

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.