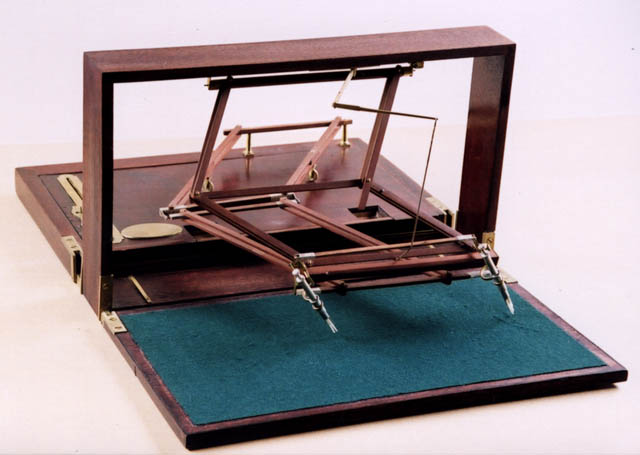

Today we associate the word polygraph mainly with the devices we call “lie detectors.” The unhidden Greek terms from which it originates simply mean “multiple writing,” which seems apt enough in light of all those movie interrogation scenes with their juddering parallel needles. But the first “polygraph machine” meriting the name long predates such cinematic clichés, and indeed cinema itself. Patented in 1803 by an Englishman named John Isaac Hawkins, it consisted essentially of twin pens, mounted side-by-side and connected by means of levers and springs so as always to move in unison. The result, in theory, was that it would make an identical copy of a letter even as the writer wrote it.

“The polygraph was pushing technology to the absolute limit,” but for years “it was nearly impossible to make it work correctly.” So says Charles Morrill, a guide at Thomas Jefferson’s estate Monticello, in the video above.

Despite the prolonged technical difficulties, the third president of the United States of America fell in love with the polygraph, “a device to duplicate letters, just the thing if you’re carrying on multiple conversations with different people all over the world. You want to keep a copy of the letter to catch yourself up, to see what you had written to cause a response” — and, of special concern to a national politician, to check on the exact degree to which the press was misquoting you.

Image by the Smithsonian, via Wikimedia Commons

Jefferson wrote nearly 20,000 letters, one of them a complaint to John Adams about suffering “under the persecution of Letters,” a condition ensuring that “from sun-rise to one or two o’clock, I am drudging at the writing table.” That the polygraph reduced this drudgery somewhat made it, in Jefferson’s words, “the finest invention of the present age.” Like technological early adopters today, Jefferson acquired each new model as it came out, the device having been continually retooled by American rights-holder Charles Willson Peale. By 1809 Peale had improved the polygraph to the point that Jefferson could write that it “has spoiled me for the old copying press the copies of which are hardly ever legible … I could not, now therefore, live without the Polygraph.” Imagine how he would’ve felt had Monticello been wired for e‑mail.

Related Content:

Thomas Jefferson’s Handwritten Vanilla Ice Cream Recipe

The First Music Streaming Service Was Invented in 1881: Discover the Théâtrophone

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.