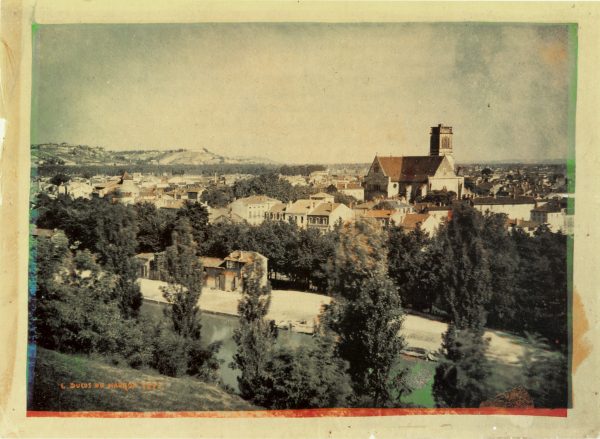

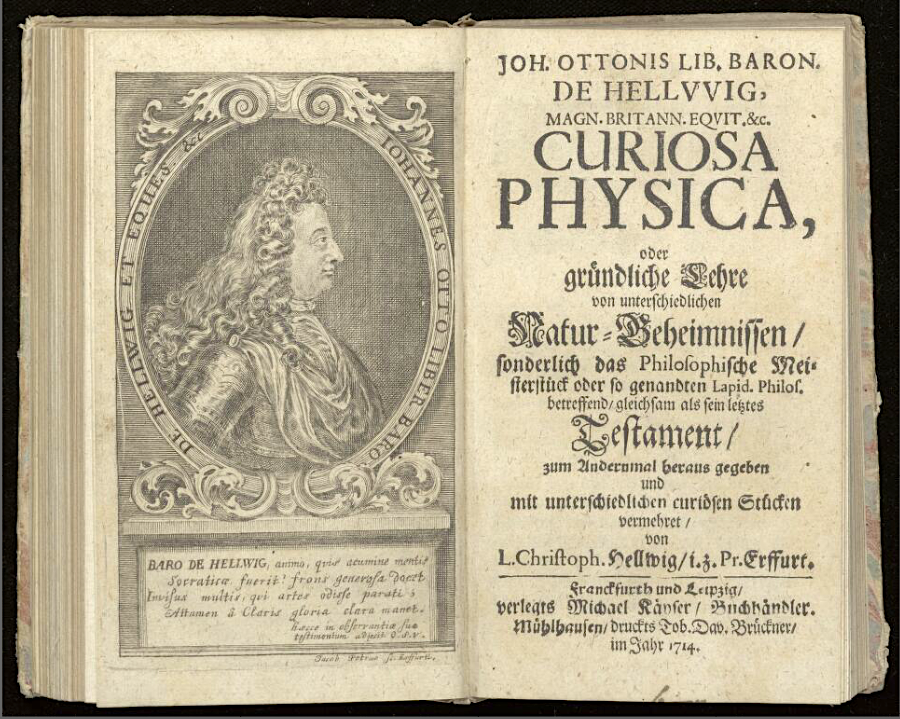

In 2018 we brought you some exciting news. Thanks to a generous donation from Da Vinci Code author Dan Brown, Amsterdam’s Ritman Library—a sizable collection of pre-1900 books on alchemy, astrology, magic, and other occult subjects—has been digitizing thousands of its rare texts under a digital education project cheekily called “Hermetically Open.” We are now pleased to report that the first 2,178 books from the Ritman project have come available in their online reading room.

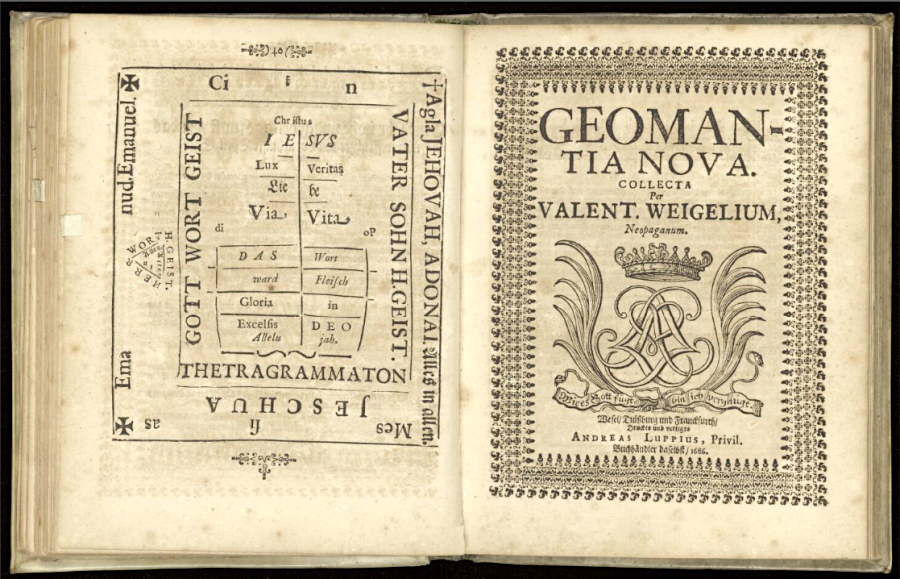

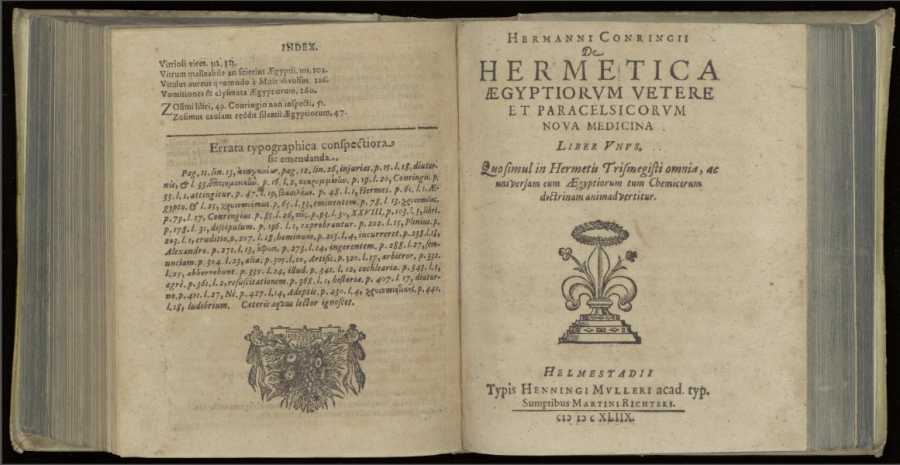

Visitors should be aware that these books are written in several different European languages. Latin, the scholarly language of Europe throughout the Medieval and Early Modern periods, predominates, and it’s a peculiar Latin at that, laden with jargon and alchemical terminology. Other books appear in German, Dutch, and French. Readers of some or all of these languages will of course have an easier time than monolingual English speakers, but there is still much to offer those visitors as well.

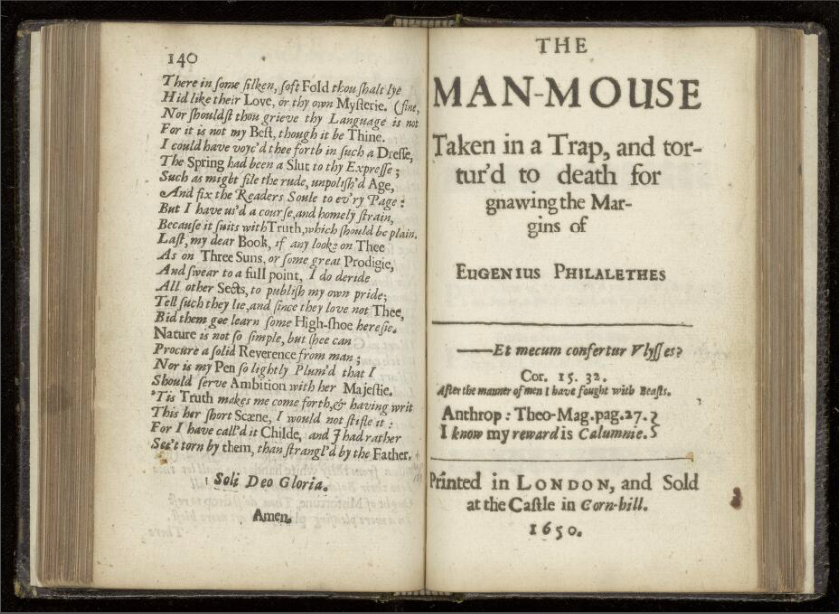

In addition to the pleasure of paging through an old rare book, even virtually, English speakers can quickly find a collection of readable books by clicking on the “Place of Publication” search filter and selecting Cambridge or London, from which come such notable works as The Man-Mouse Takin in a Trap, and tortur’d to death for gnawing the Margins of Eugenius Philalethes, by Thomas Vaughan, published in 1650.

The language is archaic—full of quirky spellings and uses of the “long s”—and the content is bizarre. Those familiar with this type of writing, whether through historical study or the work of more recent interpreters like Aleister Crowley or Madame Blavatsky, will recognize the many formulas: The tracing of magical correspondences between flora, fauna, and astronomical phenomena; the careful parsing of names; astrology and lengthy linguistic etymologies; numerological discourses and philosophical poetry; early psychology and personality typing; cryptic, coded mythology and medical procedures. Although we’ve grown accustomed through popular media to thinking of magical books as cookbooks, full of recipes and incantations, the reality is far different.

Encountering the vast and strange treasures in the online library, one thinks of the type of the magician represented in Goethe’s Faust, holed up in his study,

Where even the welcome daylight strains

But duskily through the painted panes.

Hemmed in by many a toppling heap

Of books worm-eaten, gray with dust,

Which to the vaulted ceiling creep

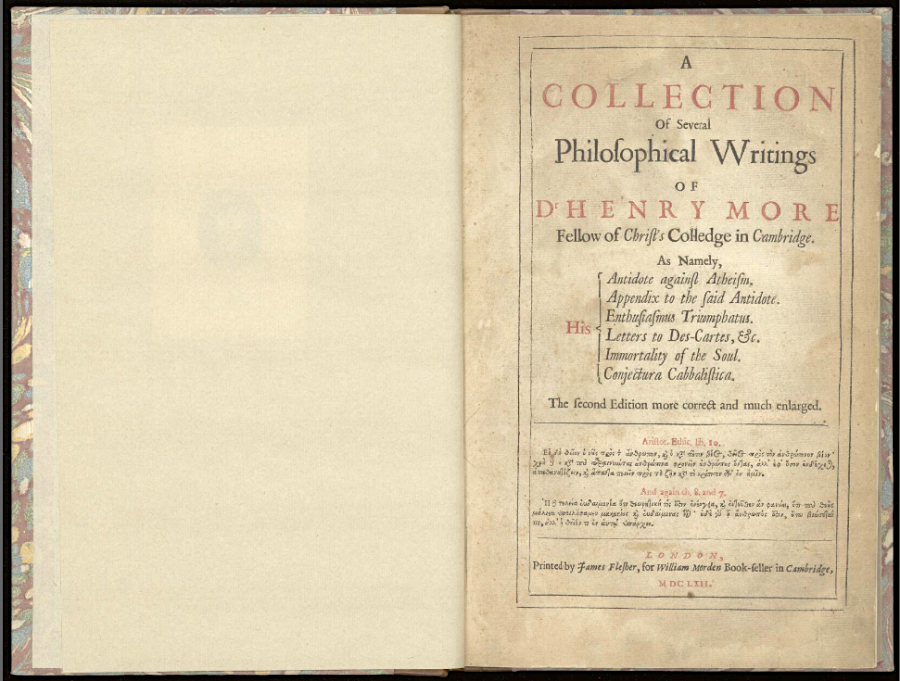

The library doesn’t only contain occult books. Like the weary scholar Faust, alchemists of old “studied now Philosophy / And Jurisprudence, Medicine,— / And even, alas! Theology.” Click on Cambridge as the place of publication and you’ll find the work above by Henry More, “one of the celebrated ‘Cambridge Platonists,’” the Linda Hall Library notes, “who flourished in mid-17th-century and did their best to reconcile Plato with Christianity and the mechanical philosophy that was beginning to make inroads into British natural philosophy.” Those who study European intellectual history know well that More’s presence in this collection is no anomaly. For a few hundred years, it was difficult, if not impossible, to separate the pursuits of theology, philosophy, medicine, and science (or “natural philosophy”) from those of alchemy and astrology. (Isaac Newton is a famous example of a mathematician/scientist/alchemist/believer in strange apocalyptic predictions.) Enter the Ritman’s new digital collection of occult texts here.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2018.

Related Content:

Discover The Key of Hell, an Illustrated 18th-Century Guide to Black Magic (1775)

Aleister Crowley Reads Occult Poetry in the Only Known Recordings of His Voice (1920)

The Surreal Paintings of the Occult Magician, Writer & Mountaineer, Aleister Crowley

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC.