Jon Kabat-Zinn Presents an Introduction to Mindfulness (and Explains Why Our Lives Just Might Depend on It)

The practice of cultivating mindfulness through meditation first took root in Europe and the U.S. in the 1960s, when Buddhist teachers from Japan, Tibet, Vietnam, and elsewhere left home, often under great duress, and taught Western students hungry for alternative forms of spirituality. Though popularized by countercultural figures like Alan Watts and Allen Ginsberg, the practice didn’t seem at first like it might reach those who seemed to need it most — stressed out denizens of the corporate world and military industrial complex who hadn’t changed their consciousness with mind-altering drugs, or left the culture to become monastics.

Then professor of medicine Jon Kabat-Zinn came along, stripped away religious and new age contexts, and began redesigning mindfulness for the masses in 1979 with his mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) program. Now everyone knows, or thinks they know, what mindfulness is. As meditation teacher Lokadhi Lloyd tells The Guardian, Kabat-Zinn is “Mr Mindfulness in relation to our secular strand. Without him, I don’t think mindfulness would have risen to the prominence it has.”

His secularization of mindfulness, however, has not, in practical terms, taken it very far from its roots, which explains why Kabat-Zinn’s groundbreaking 1990 book Full Catastrophe Living receives high praise from Buddhist teachers like Joseph Goldstein, Sharon Salzburg, and Kabat-Zinn’s own former Zen teacher, Thich Nhat Hanh.

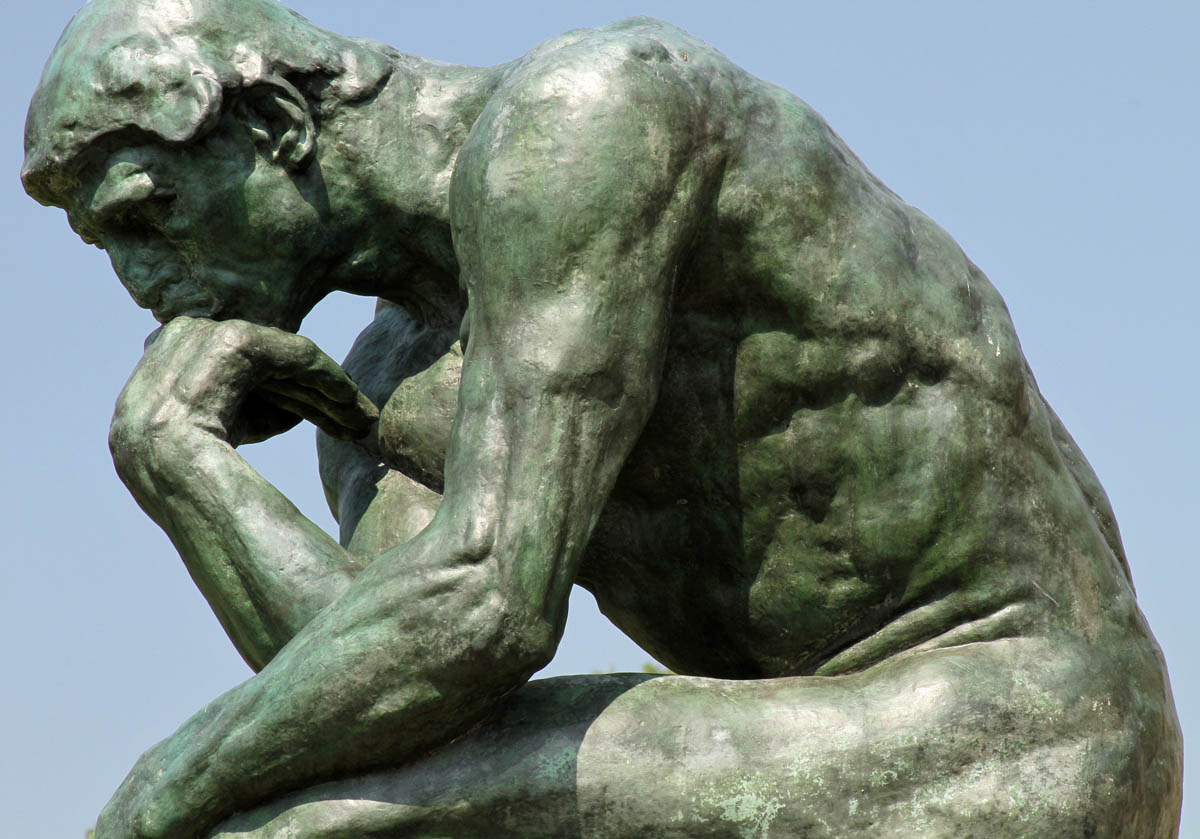

While Kabat-Zinn says he himself is not (or is no longer) a Buddhist, his definitions of mindfulness might sound just close enough to those who study and practice the religion. As he says in the short segment at the top: “It’s paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment, non-judgmentally.” And then, “sometimes,” he says, “I like to add, as if your life depended on it.” The quality of our lives, the clarity of our lives, and the depth and richness of our lives depend on our ability to be aware of what’s happening around and inside us. This ability, Kabat-Zinn insists, is the inheritance of all human beings. It can be found in spiritual practices around the world. No one owns a patent on awareness.

Nevertheless, Kabat-Zinn is particularly leery of what he calls McMindfulness, the commodity-driven industry selling coloring books, apps, puzzles, t‑shirts, and novelties touting mindful benefits. Mindfulness based stress reduction is “not a trick,” he says. It isn’t something we buy and try out here and there. “MBSR is exceedingly challenging,” Kabat-Zinn writes in Full Catastrophe Living. “In many ways, being in the present moment with a spacious orientation toward what is happening may really be the hardest work in the world for us humans. At the same time, it is also infinitely doable.” It can also be highly unpleasant, forcing us to sit with the things we’d rather ignore about ourselves. Why should we do it? We might consider the alternatives.

MBSR began (“in the basement of the University of Massachusetts Medical Center,” notes NPR) helping patients with chronic pain recover. It proved so effective, Kabat-Zinn applied the insight more globally — “using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness.” This is not a cure-all, but a way of living that reduces unnecessary suffering caused by overactive discursive thinking, which traps us in patterns of blame, shame, fear, regret, judgment, and self-criticism (illustrated in Scottish psychologist R.D. Laing’s book of neurotic narratives, Knots) — traps us, that is, in stories about the past and future, which affect our physical and mental health, our work, and our relationships.

The medical evidence for mindfulness has only begun to catch up with Kabat-Zinn’s work, yet it weighs heavily on the side of the outcomes he has seen for over 40 years. MBSR also comes highly recommended by Harvard neuroscientist Sara Lazar and trauma expert Bessel Van Der Kok, among so many others who have done the research. The evidence is why, as you can see in the longer presentations above at Dartmouth and Google, Kabat-Zinn has become something of an evangelist for mindfulness. “If this is another fad, I don’t want to have any part of it,” he says. “If in the past 50 years I had found something more meaningful, more healing, more transformative and with more potential social impact, I would be doing that.”

As Kabat-Zinn’s 2005 book, Wherever You Go, There You Are, shows, we can bring what happens in meditation into our everyday life, letting assumptions go, and “letting life become both the meditation teacher and the practice, moment by moment, no matter what arises,” he tells Mindful magazine. This isn’t about escaping into blissed out moments of Zen. It’s fostering “deep connections,” over and over again, with ourselves, families, friends, communities, the planet we live on, and, in turn, “the future that we’re bequeathing to our future generations.”

Related Content:

Daily Meditation Boosts & Revitalizes the Brain and Reduces Stress, Harvard Study Finds

De-Mystifying Mindfulness: A Free Online Course by Leiden University

Stream 18 Hours of Free Guided Meditations

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...An Online Archive of Beautiful, Early 20th Century Japanese Postcards

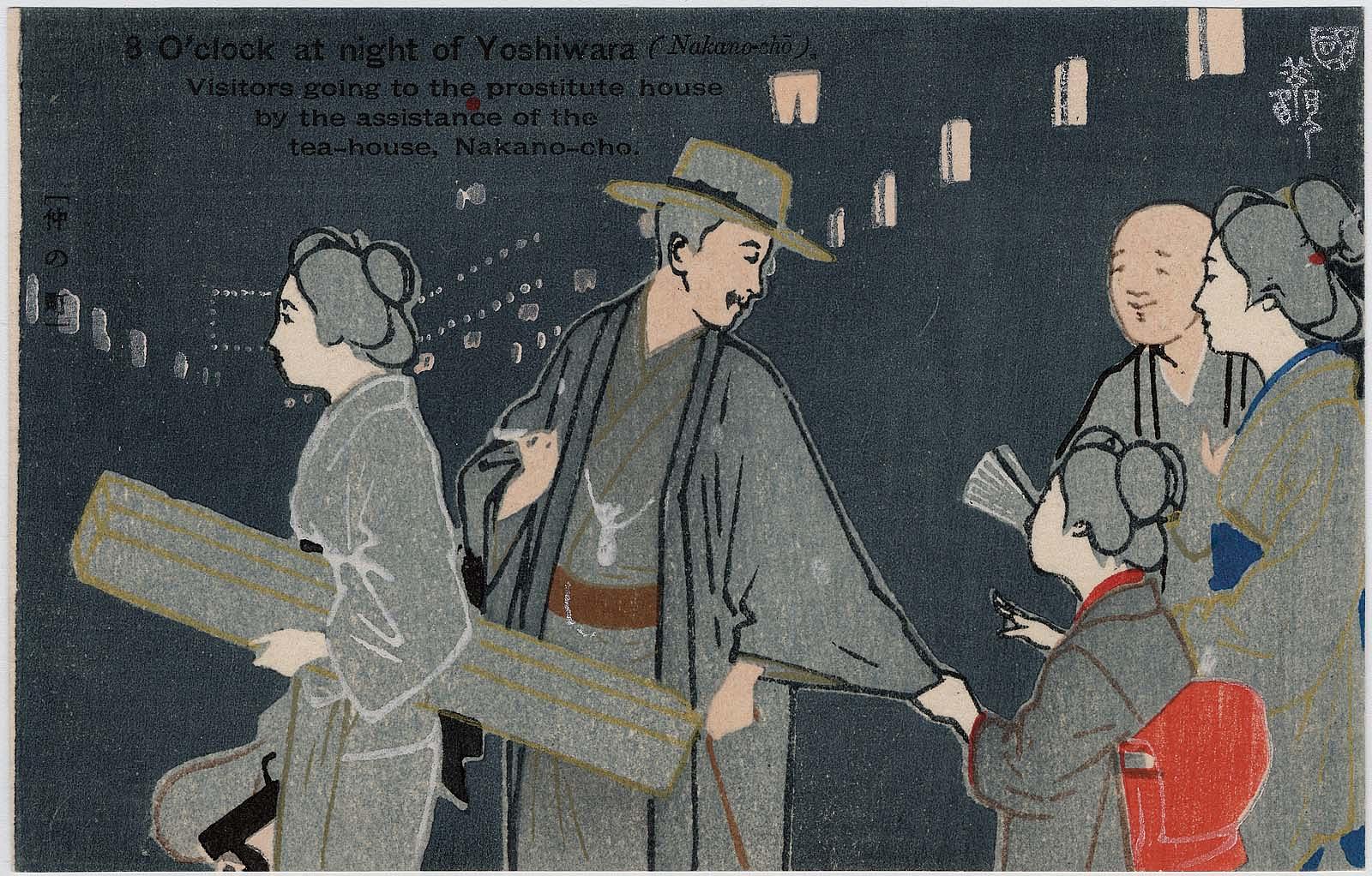

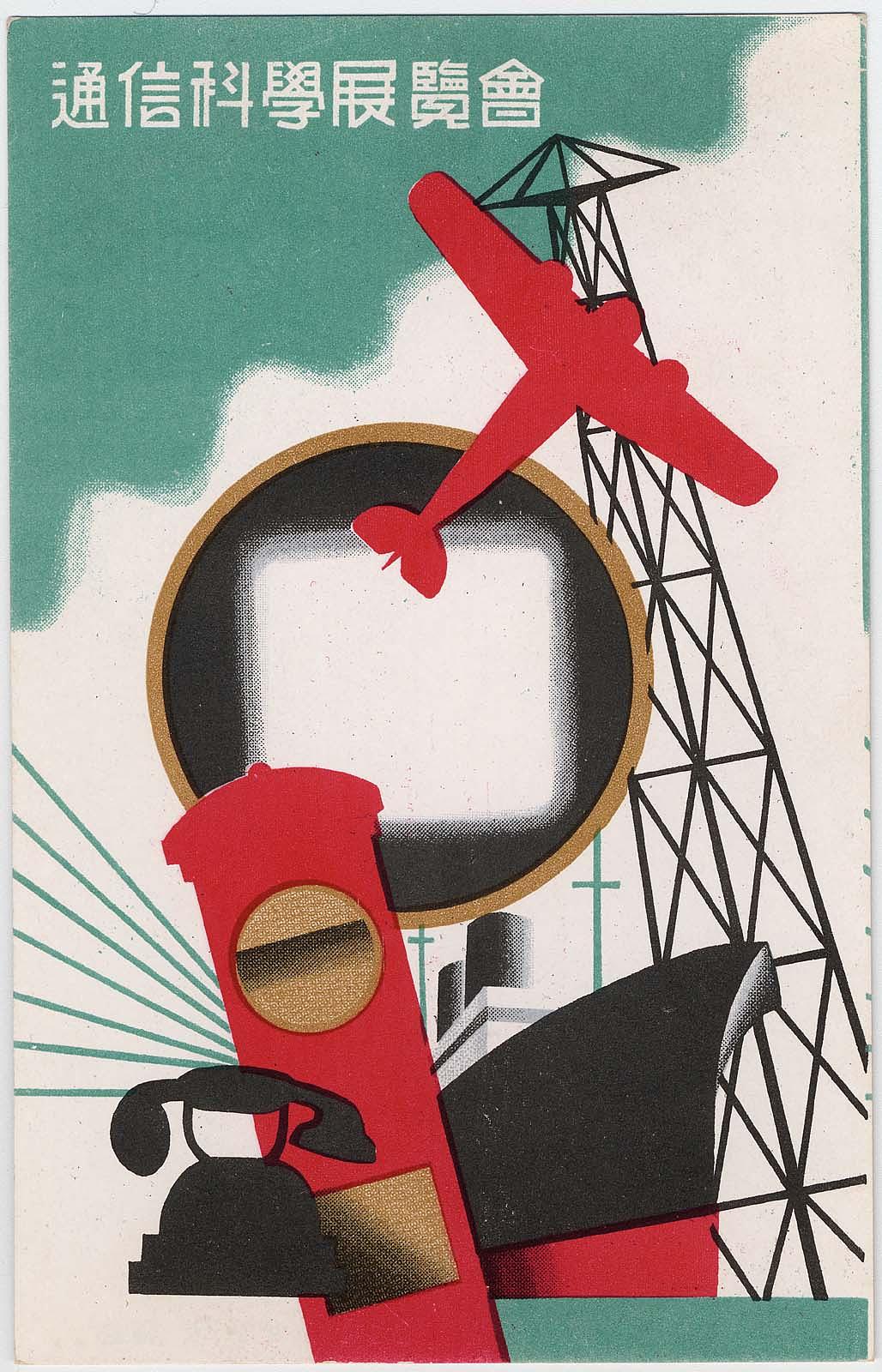

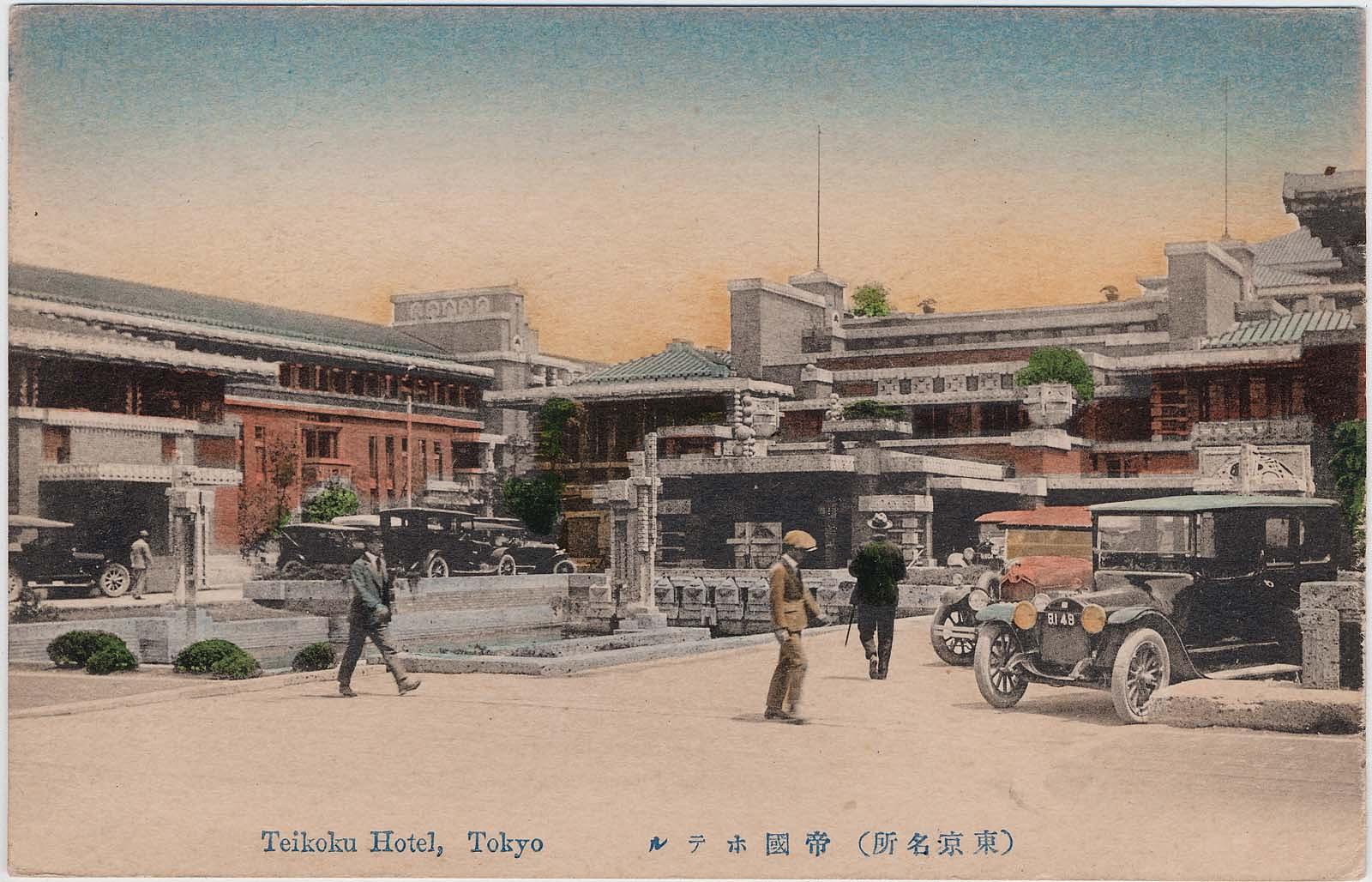

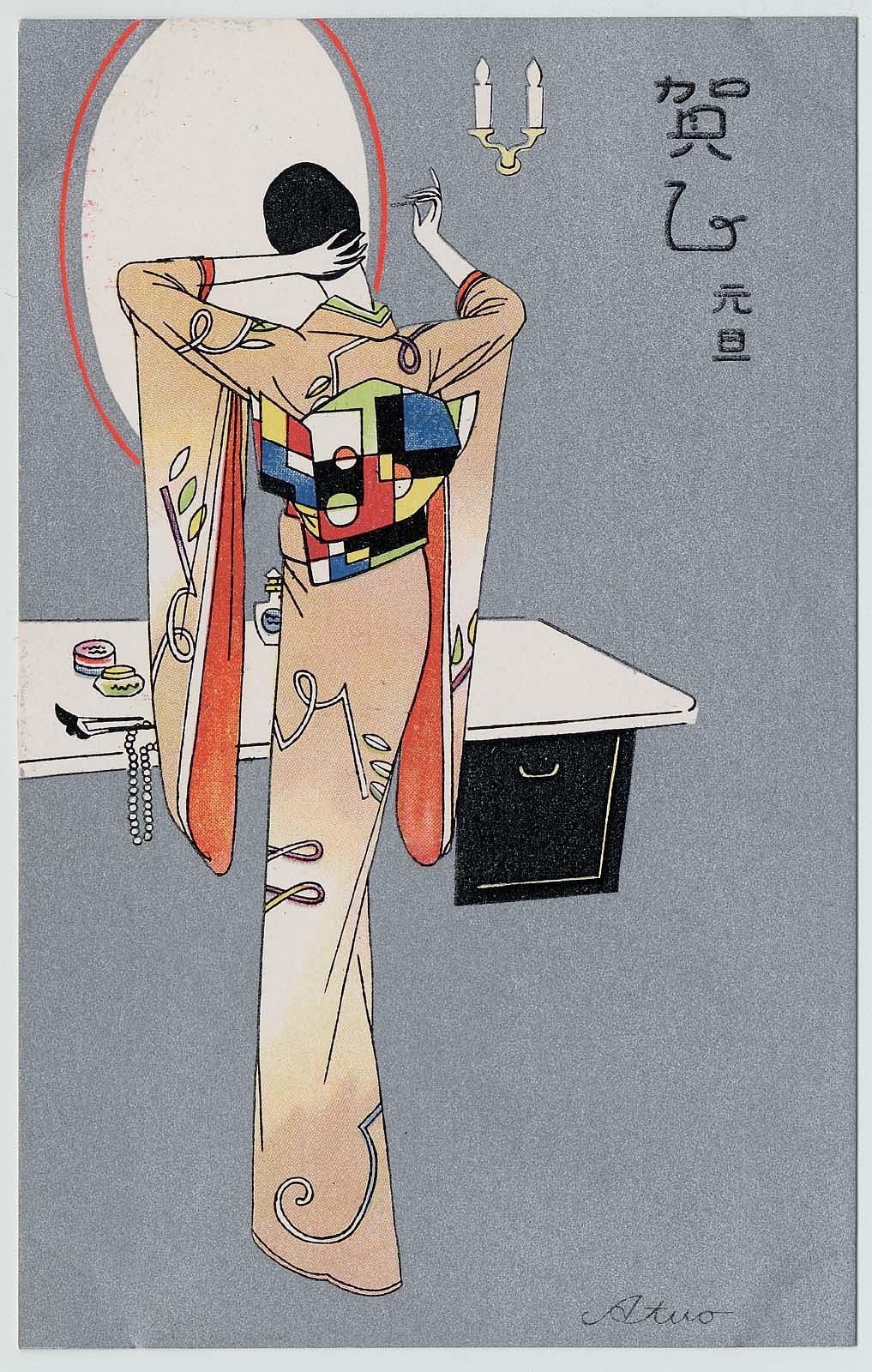

The world thinks of Japan as having transformed itself utterly after its defeat in the Second World War. And indeed it did, into what by the nineteen-eighties looked like a gleaming, technology-saturated condition of ultra-modernity. But the standard version of modernity, as conceived of in the early 20th century with its trains, telephones, and electricity, came to Japan long before the war did. “Between 1900 and 1940, Japan was transformed into an international, industrial, and urban society,” writes Museum of Fine Arts Boston curator Anne Nishimura Morse. “Postcards — both a fresh form of visual expression and an important means of advertising — reveal much about the dramatically changing values of Japanese society at the time.”

These words come from the introductory text to the MFA’s 2004 exhibition “Art of the Japanese Postcard,” curated from an archive you can visit online today. (The MFA has also published it in book form.) You can browse the vintage Japanese postcards in the MFA’s digital collections in themed sections like architecture, women, advertising, New Year’s, Art Deco, and Art Nouveau.

These represent only a tiny fraction of the postcards produced in Japan in the first decades of the twentieth century, when that new medium “quickly replaced the traditional woodblock print as the favored tableau for contemporary Japanese images. Hundreds of millions of postcards were produced to meet the demands of a public eager to acquire pictures of their rapidly modernizing nation.”

The earliest Japanese postcards “were distributed by the government in connection with the Russo-Japanese War (1904–5), to promote the war effort. Almost immediately, however, many of Japan’s leading artists — attracted by the informality and intimacy of the postcard medium — began to create stunning designs.” The work of these artists is collected in a dedicated section of the online archive, where you’ll find postcards by the commercial graphic-design pioneer Suguira Hisui; the French-educated, highly Western-influenced Asai Chi; the multitalented Ota Saburo, known as the illustrator of Kawabata Yasunari’s The Scarlet Gang of Asakusa; and Nakazawa Hiromitsu, creator of the “diver girl” long well-known among Japanese-art collectors.

Surprisingly, Nakazawa’s diver girl (also known as the “mermaid,” but most correctly as “Heroine Matsuzake” of a popular play at the time) seems not to have been among the possessions of cosmetics billionaire and art collector Leonard A. Lauder, who donated more than 20,000 Japanese selections from his vast postcard collection to the MFA. “In 1938 or ’39, a boy of five or six, or maybe seven, was so enthralled by the beauty of a postcard of the Empire State Building that he took his entire five-cent allowance and bought five of them,” writes the New Yorker’s Judith H. Dobrzynski. The youngster thrilling to the paper image of a skyscraper was, of course, Lauder — who couldn’t have known how much, in that moment, he had in common with the equally modernity-intoxicated people on the other side of the world.

via Flashbak

Related content:

Advertisements from Japan’s Golden Age of Art Deco

Vintage 1930s Japanese Posters Artistically Market the Wonders of Travel

Glorious Early 20th-Century Japanese Ads for Beer, Smokes & Sake (1902–1954)

An Eye-Popping Collection of 400+ Japanese Matchbox Covers: From 1920 through the 1940s

View 103 Discovered Drawings by Famed Japanese Woodcut Artist Katsushika Hokusai

Download 2,500 Beautiful Woodblock Prints and Drawings by Japanese Masters (1600–1915)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Read More...A Whirlwind Architectural Tour of the New York Public Library–“Hidden Details” and All

The New York Public Library opened in 1911, an age of magnificence in American city-building. Eighteen years before that, writes architect-historian Witold Rybczynski, “Chicago’s Columbian Exposition provided a real and well-publicized demonstration of how the unruly American downtown could be tamed though a partnership of classical architecture, urban landscaping, and heroic public art.” Modeled after Europe’s urban civilization, the “White City” built on the ground of the Columbian Exposition inspired a generation of American architects and planners including John Nolen, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., and John Carrère, co-designer of the New York Public Library.

Carrère appears in the Architectural Digest tour video of the NYPL building above — or at least his bust does, prominently placed as it is on the landing of one of the grand staircases leading up from the main entrance. The staircases are marble, as is much of else; when the NYPL opened after nine years of construction, so the tour’s narration informs us, it did so as the largest marble-clad structure in the country.

On the soundtrack we have not just one guide, but three: NYPL visitor volunteer program manager Keith Glutting, design historian Judith Gura, and architectural historian Paul Ranogajec. Together they tell the story of this venerable American building, and also point out the “hidden details” that a visitor might not otherwise notice.

Take the terrace on which the whole building stands, a feature of the European villa and palace tradition. Or the murals depicting the history of the written word from Moses’ stone tablets on down. Or the pneumatic tubes, artifacts of the analog information-technology system in use before the NYPL computerized in the nineteen-seventies. Or the rendering of the world in the library’s formidable map room that mistakenly depicts California as an island (not that every New Yorker would disagree). The video also includes other, even lesser-seen wonders both old and new, from a 1455 Gutenberg Bible — the first in the New World — to the automated trolley system that brings books out of the stacks. But it is the building itself that inspires wonder, its extravagant solidity and detail that hark back to a time of consensus, however brief, that nothing was too good for ordinary people.

Related content:

The New York Public Library Announces the Top 10 Checked-Out Books of All Time

Watch 52,000 Books Getting Reshelved at The New York Public Library in a Short, Timelapse Film

The New York Public Library Unveils a Cutting-Edge Train That Delivers Books

The New York Public Library Creates a List of 125 Books That They Love

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Read More...The History of Birth Control: From Alligator Dung to The Pill

The history of birth control is almost as old as the history of the wheel.

Pessaries dating to Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt provide the launching pad for documentarian Lindsay Holiday’s overview of birth control throughout the ages and around the world.

Holiday’s History Tea Time series frequently delves into women’s history, and her pledge to donate a portion of the above video’s ad revenue to Pathfinder International serves as reminder that there are parts of the world where women still lack access to affordable, effective, and safe means of contraception.

One goal of the World Health Organization’s Ending Preventable Maternal Mortality initiative is for 65% of women to be able to make informed and empowered decisions regarding sexual relations, contraceptive use, and their reproductive health by 2025.

As Holiday points out, expense, social stigma, and religious edicts have impacted ease of access to birth control for centuries.

The further back you go, you can be certain that some methods advocated by midwives and medicine women have been lost to history, owing to unrecorded oral tradition and the sensitive nature of the information.

Holiday still manages to truffle up a fascinating array of practices and products that were thought — often erroneously — to ward off unwanted pregnancy.

Some that worked and continue to work to varying degrees, include barrier methods, condoms, and more recently the IUD and The Pill.

Definitely NOT recommended: withdrawal, holding your breath during intercourse, a post-coital sneezing regimen, douching with Lysol or Coca-Cola, toxic cocktails of lead, mercury or copper salt, anything involving alligator dung, and slugging back water that’s been used to wash a corpse.

As for silphium, an herb that likely did have some sort of spermicidal properties, we’ll never know for sure. By 1 CE, demand outstripped supply of this remedy, eventually wiping it off the face of the earth despite increasingly astronomical prices. Fun fact: silphium was also used to treat sore throat, snakebite, scorpion stings, mange, gout, quinsy, epilepsy, and anal warts

The history of birth control can be considered a semi-secret part of the history of prostitution, feminism, the military, obscenity laws, sex education and attitudes toward public health.

From Margaret Sanger and the 60,000 women executed as witches in the 16th and 17th centuries, to economist Thomas Malthus’ 1798 Essay on the Principle of Population and legendary adventurer Giacomo Casanova’s satin ribbon-trimmed jimmy hat, this episode of History Tea Time with Lindsay Holiday touches on it all.

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Related Content

The Story Of Menstruation: Watch Walt Disney’s Sex Ed Film from 1946

Read More...A Master List of 1,700 Free Courses From Top Universities: A Lifetime of Learning on One Page

For the past 15 years, we’ve been busy rummaging around the internet and adding courses to an ever-growing list of Free Online Courses, which now features 1,700 courses from top universities. Let’s give you the quick overview: The list lets you download audio & video lectures from schools like Stanford, Yale, MIT, Oxford, Harvard and many other institutions. Generally, the courses can be accessed via YouTube, iTunes or university web sites, and you can listen to the lectures anytime, anywhere, on your computer or smart phone. We haven’t done a precise calculation, but there’s about 50,000 hours of free audio & video lectures here. Enough to keep you busy for a very long time–something that’s useful during these socially distant times.

Right now you’ll find 200 free philosophy courses, 105 free history courses, 170 free computer science courses, 85 free physics courses and 55 Free Literature Courses in the collection, and that’s just beginning to scratch the surface. You can peruse sections covering Astronomy, Biology, Business, Chemistry, Economics, Engineering, Math, Political Science, Psychology and Religion.

Here are some highlights from the complete list of Free Online Courses. We’ve added a few unconventional/vintage courses in the mix just to keep things interesting.

- A History of Philosophy in 81 Video Lectures: From Ancient Greece to Modern Times — Free Online Video — Arthur Holmes, Wheaton College

- A Romp Through Ethics for Complete Beginners - Various Formats – Marianne Talbot, Oxford University

- Ancient Greek History — Various Formats — Donald Kagan, Yale

- Creative Reading and Writing by William S. Burroughs — Free Online Audio — Naropa University

- Critical Reasoning for Beginners — Various Formats – Marianne Talbot, Oxford

- Deep Learning — Free Online Video — Vincent Vanhoucke, Google

- Edible Education 101 – Free Online Video – Michael Pollan, UC Berkeley

- Financial Markets — Various Formats — Robert Shiller, Yale

- Growing Up in the Universe – Free Online Video – Richard Dawkins, Oxford

- Harvard’s Introductory Computer Science Course - Free Online Course — David Malan, Harvard

- Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Faulkner – Various Formats – Wai Chee Dimock, Yale

- How to Listen to Music — Various Formats — Craig Wright, Yale

- Human Behavioral Biology – Various Formats – Robert Sapolsky, Stanford

- Introduction to the Old Testament (Hebrew Bible) – Free Online Video — Christine Hayes, Yale.

- Lectures on Digital Photography — Free Online Video — Marc Levoy, Stanford/Google

- Physics for Future Presidents – Free Online Video – Richard Muller, UC Berkeley

- Science and Cooking: From Haute Cuisine to the Science of Soft Matter — Various Formats — Team taught, Harvard

- Speak Italian with Your Mouth Full - Various Formats — MIT, Dr. Paola Rebusco

- The American Novel Since 1945 – Various Formats – Amy Hungerford, Yale

- The Central Philosophy of Tibet — Free Online Audio – Robert Thurman, Columbia University

- The Character of Physical Law (1964) - Free Online Video — Richard Feynman, Cornell

- The Tempest - Free Online Audio — Allen Ginsberg, Naropa

- Walter Kaufmann Lectures on Nietzsche, Kierkegaard and Sartre — Free Online Audio

The complete list of courses can be accessed here: 1,700 Free Online Courses from Top Universities. For more enriching material, see our other collections below.

Related Content:

1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free.

4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Learn 45+ Languages Online for Free: Spanish, Chinese, English & More.

200 Online Certificate & Microcredential Programs from Leading Universities & Companies.

Read More...

Explore a Big Archive of Vintage Early Comics: 1700–1929

The popularity of graphic novels (and more than a few extremely lucrative superhero movie franchises) have conferred respectability on comics.

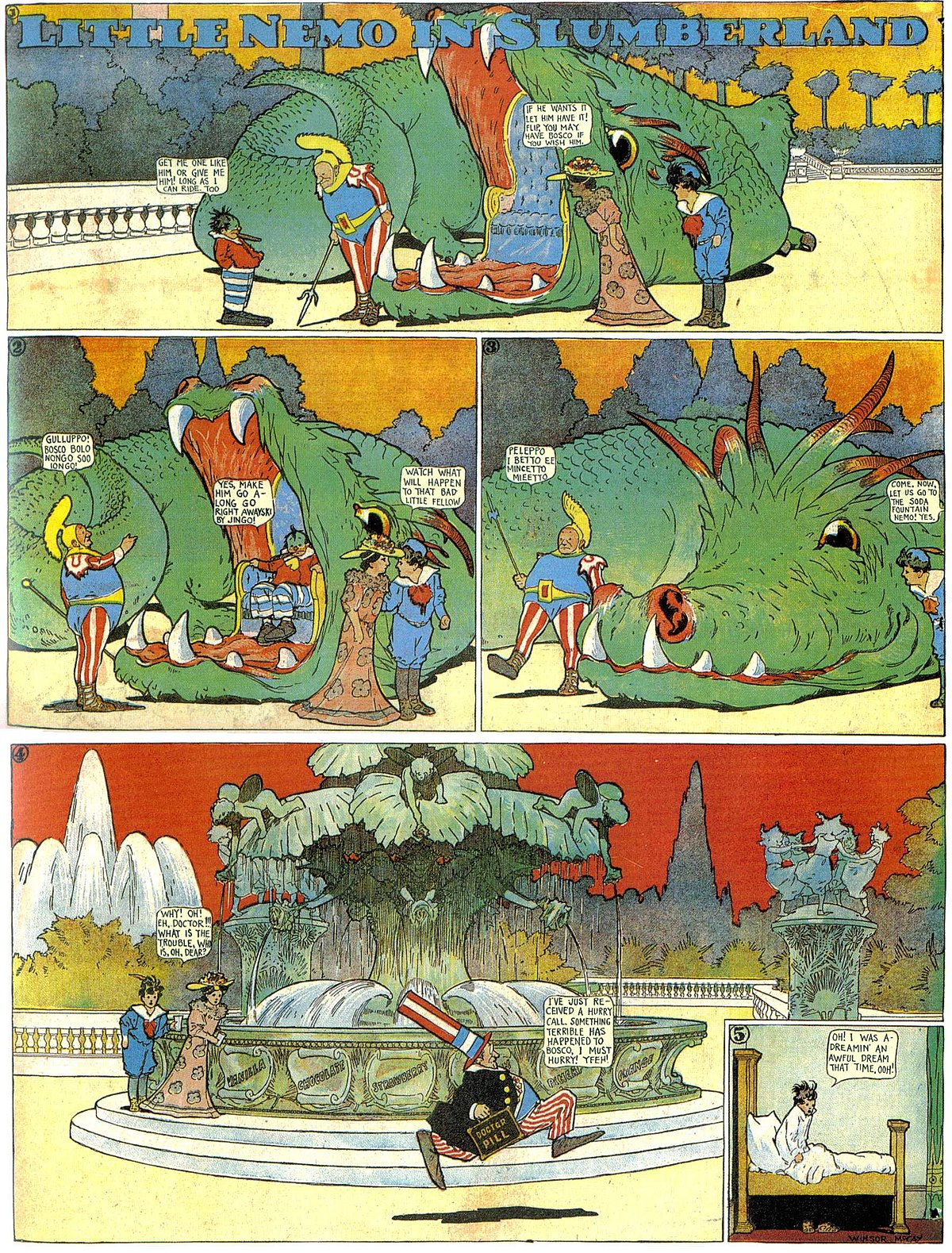

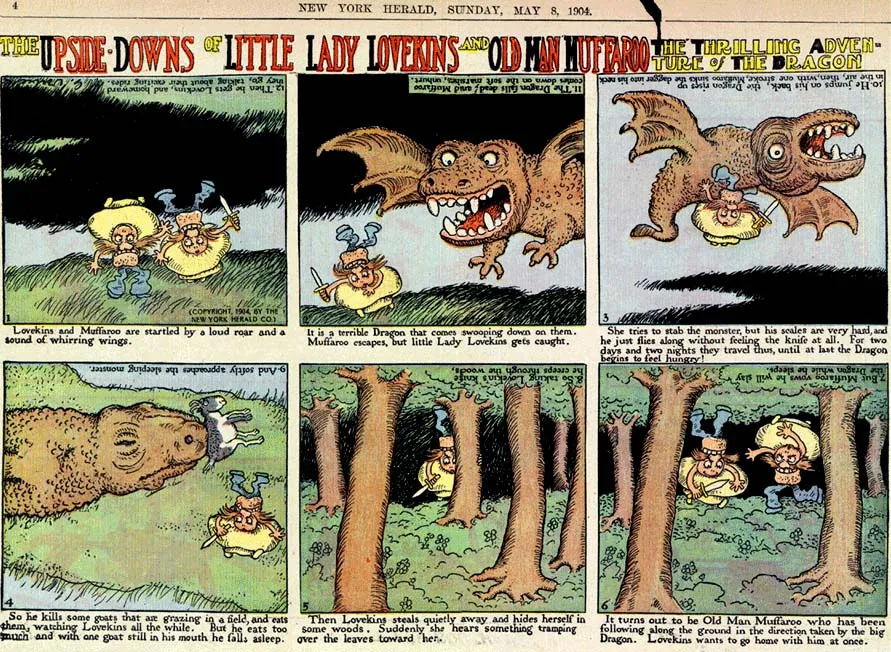

Handsome reissues of such stunning early works as Winsor McKay’s Little Nemo in Slumberland, George Herriman’s Krazy Kat, and Frank King’s Walt and Skeezix suggest that readers’ appetite for vintage comics extends deeper and further back than mere nostalgia for the Sunday funnies of their youth.

Artist Andy Bleck’s Andy’s Early Comics Archive is an excellent resource for those seeking to discover early examples of the form that have yet to be reissued in a collected edition. (Fair warning: reflecting the attitudes of the time, the collection does inevitably contains some racist imagery. Such imagery won’t be on display in this post.)

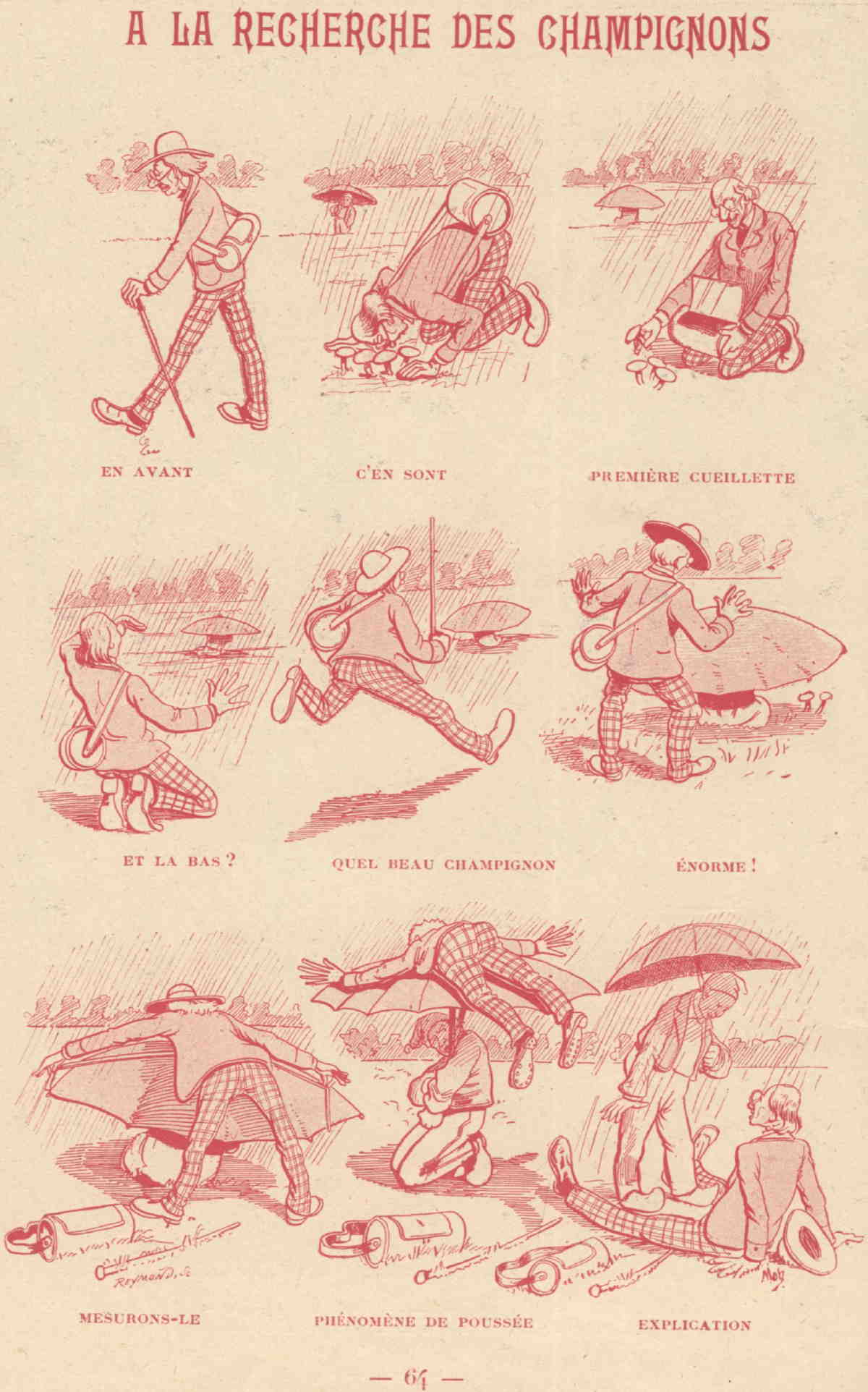

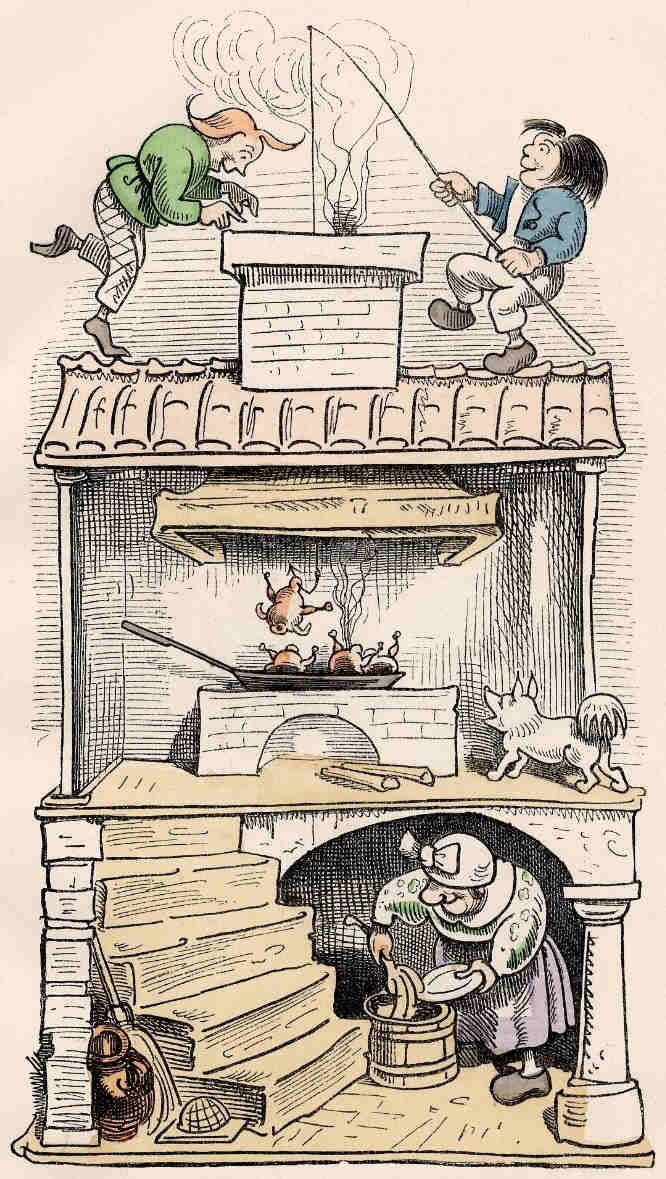

Bleck, the creator of Konky Kru, a beautifully simple, wordless series, as well as several self-published mini comics, takes a historian’s interest in his subject, beginning with the William Hogarth engravings A Harlot’s Progress from 1730:

The famous ‘progressions’ by Hogarth were not actually comics. The images don’t lead into and don’t interact with each other. Each shows a distinct, separate stage of a longer story. However, because of their great popularity, they established the very notion of telling entertaining stories with a series of pictures and so became a highly influential stepping stone for future developments.

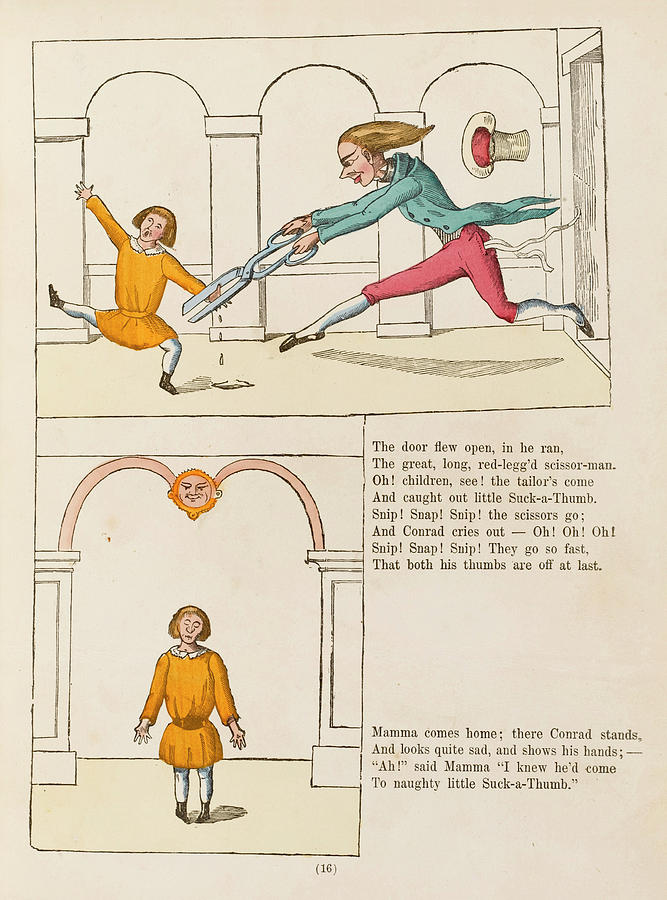

He also cites the influence of British political cartoons, Chinese woodcuts, illustrated fairy tales and nursery rhymes, and Heinrich Hoffmann’s Struwwelpeter, a book that terrified children into behaving by depicting the monstrous consequences befalling those who failed to do so.

Ironically, Franz Joseph Goez’s Lenardo und Blandine, an actual graphic novelette from 1783, “probably had little influence:”

It was too ahead of its time as far as the comic structure is concerned. In content, it was delightfully very much of its time, full of outrageous melodrama.

Things continued to evolve in the second half of the 19th-century, with picture broadsheets for children, such as the ones starring Wilhelm Busch’s wildly popular Max and Moritz. (See an English translation here.)

Bleck traces the birth of modern comics, whose storytelling vocabulary continues today, to the beginning of the 20th century, with American newspaper strips and particularly, the Sunday funnies:

The newspaper format was much larger and cheaper, providing a lot more empty space to fill. The audience was less sophisticated, but (possibly because of this) more open to a particular type of experimentation, despite the dumb and lowbrow humor… these American Sunday pages became the breeding ground for something new. Weirder, rougher, slapdashier. Also easier, for children, but not childish. More popular. More … somethingier.

Maybe it was that new type of human being, the urban immigrant, who was most prepared and eager to pay for all this new visual goings on.

Andy’s Early Comics Archive can be searched chronologically, or alphabetically by artist’s name. Enter here.

Related Content

Read The Very First Comic Book: The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck (1837)

Download Over 22,000 Golden & Silver Age Comic Books from the Comic Book Plus Archive

Download 15,000+ Free Golden Age Comics from the Digital Comic Museum

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...

100-Year-Old Music Recordings Can Now Be Heard for the First Time, Thanks to New Digital Technology

If you were listening to recorded music around the turn of the twentieth century, you listened to it on cylinders. Not that anyone alive today was listening to recorded music back then, and much of it has since been lost. Invented by Alexander Graham Bell (better known for his work on an even more popular device known as the telephone), the recording cylinder marked a considerable improvement on Thomas Edison’s earlier tinfoil phonograph. Never hesitant to capitalize on an innovation — no matter who did the innovating — Edison then began marketing cylinders of his own, soon turning his own name into the format’s most popular and recognizable brand.

“Edison set up coin-operated phonograph machines that would play pre-recorded wax cylinders in train stations, hotel lobbies, and other public places throughout the United States,” writes Atlas Obscura’s Sarah Durn. They also became the medium choice for hobbyists. “One of the most famous is Lionel Mapleson,” says Jennifer Vanasco in an NPR story from earlier this month.

“He recorded his family,” but “he was also the librarian for the Metropolitan Opera. And in the early 1900s, he recorded dozens of rehearsals and performances. Listening to his work is the only way you can hear pre-World War I opera singers with a full orchestra”: German soprano Frieda Hempel, singing “Evviva la Francia!” above.

The “Mapleson Cylinders” constitute just part of the New York Public Library’s collection of about 2,700 recordings in that format. “Only a small portion of those cylinders, around 175, have ever been digitized,” writes Durn. “The vast majority of the cylinders have never even been played in the generations since the library acquired them.” Most have become too fragile to withstand the needles of traditional players. Enter Endpoint Audio Labs’ $50,000 Cylinder and Dictabelt Machine, which uses a combination of needle and laser to read and digitize even already-damaged cylinders without harm. Only seven of Endpoint’s machines exist in the world, one of them a recent acquisition of the NYPL’s, which will now be able to play many of its cylinders for the first time in more than a century.

Some of these cylinders are unlabeled, their contents unknown. Curator Jessica Wood, as Velasco says, is hoping to “hear a birthday party or something that tells us more about the social history at the time, even someone shouting their name and explaining they’re testing the machine, which is a pretty common thing to hear on these recordings.” She knows that the NYPL’s collection has “about eight cylinders from Portugal, which may be some of the oldest recordings ever made in the country,” as well as “five Argentinian cylinders that have preserved the sound of century-old tango music.” In the event, from the first cylinder she puts on for NPR’s microphone issue familiar words: “Hello, my baby. Hello, my honey. Hello, my ragtime gal.” This listening experience perhaps felt like something less than time travel. But then, were you really to go back to 1899, what song would you be more likely to hear?

Related content:

Hear Singers from the Metropolitan Opera Record Their Voices on Traditional Wax Cylinders

A Beer Bottle Gets Turned Into a 19th Century Edison Cylinder and Plays Fine Music

400,000+ Sound Recordings Made Before 1923 Have Entered the Public Domain

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...The Birth of the Blues Brothers: How Dan Aykroyd & John Belushi Started Introducing a New Generation to the Blues

What were the Blues Brothers? A comedy sketch? A parody act? A real band? A celebrity soul artist tribute? All of the above, yes. The musical-comedic duo of Dan Aykroyd and John Belushi turned a ludicrous beginning in bumble bee costumes — not dark suits, fedoras, and Ray-Bans — into a musical act that “exposed a generation to the brilliance of blues and soul legends like John Lee Hooker and Aretha Franklin,” as Darren Weale writes at Loudersound.

That’s quite an accomplishment for a couple of improv comedians on a fledgling late-night comedy show that did not seem, in its first year, like it would stick around long. It was during that anarchic period when the Killer Bees became recurring characters on the show, appearing 11 times (despite the studio note, “Cut the bees,” which Lorne Michaels pointedly ignored).

The bees were the first incarnation of the Blues Brothers, two years before their actual debut in Season 4. (See a later appearance from that season, introduced by Garrett Morris, just above).

A January 17, 1976 appearance of the bees featured “Howard Shore and his All Bee Band,” consisting of “Aykroyd on the harmonica and Belushi on vocals belting out a blues classic very much in the style of the future Elwood and ‘Joliet’ Jake Blues,” notes History.com. They had the beginnings of an act, but the look and the personas would come later, “during the hiatus between SNL seasons two and three” in 1977, while Belushi filmed Animal House in Eugene, Oregon and fell under the spell of local bluesman Curtis Salgado, future harmonica player for Robert Cray.

Salgado “sure turned John on to blues music,” says Aykroyd. “He steeped him in blues culture.” Salgado himself describes how Belushi won him over on their first meeting: “I’m packing up my harps, trying to break free, when he says, ‘I’m going to have Ray Charles on the show.’ ” Salgado also gave Belushi a lesson in playing it straight, even when he played the blues for laughs. When the comic performed the song “Hey Bartender” to a packed house one night, in character as Joe Cocker, his mentor gave him a post-show dressing down.

“He asks me, ‘What did you think?’”

“I say, ‘John, it’s Joe Cocker.’”

‘Yes, I do Joe on Saturday Night Live.’

“I punch his chest and say, ‘You need to do this from here [pointing at his heart] and be yourself.’ After that he didn’t mimic any more. He was himself.”

Taking the look of Jake and Elwood from Salgado, but developing the character as his swaggering self, Belushi “came back from Oregon with a lust for the blues,” his widow, Judith, recalls. “He had tapes in his pockets and went to clubs.” (See the duo play “Hey Bartender” at the Universal Amphitheater in 1978, below.)

The name was the brainchild of SNL musical director Howard Shore (who would go on to write the Lord of the Rings film scores), who happened to be present when the two conceived the characters at a bar. Their 1978 debut — made over the protests of Lorne Michaels (who didn’t get it) — made them instant stars.

Paul Shaffer spun their origin story in his introduction, “claiming that they had been discovered in 1969 by the fictional ‘Marshall Checker,” writes Mental Floss. He went on:

Today they are no longer an authentic blues act, but have managed to become a viable commercial product. So now, let’s join “Joliet” Jake and his silent brother Elwood — the Blues Brothers.

With that, the never-authentic blues act did, indeed, become a viable commercial product. “Things started to move quickly,” Weale writes. “Record executive Michael Klenfner took John and Dan to see Ahmet Ertegün at Atlantic Records. He signed the Blues Brothers up.” They were a real act, and two years later, real movie stars with the release of John Landis’ The Blues Brothers, a film that fully delivered on the duo’s comic promises, while gleefully giving the spotlight away to its huge cast of soul and blues legends

Related Content:

Saturday Night Live’s Very First Sketch: Watch John Belushi Launch SNL in October, 1975

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Make Your Own Medieval Memes with a New Tool from the Dutch National Library

As much joy as internet memes have given you over the years, you may have struggled to explain them to those unfamiliar with the concept. But if you’ve found it a tall order to articulate the power of found images crudely overlaid with text to, say, your parents, imagine attempting to do the same to an ancestor from the fourteenth century. Introducing memes to a medieval person, the best strategy would presumably be to begin not with sardonic Willy Wonka, the guy distracted by another girl, or The Most Interesting Man in the World, but memes with familiar medieval imagery. Thanks to KB, the national library of the Netherlands, you can now make some of you own with ease.

“On www.medievalmemes.org visitors can use images taken from the Dutch national library’s medieval collection and turn them into memes,” says Medievalists.net. “When using the meme generator, people actively create new contexts for these historic images by adding current captions. The available images are accompanied by explanatory videos, providing viewers with background information and showing them that, much like today, people in the Middle Ages used images to comment on their surroundings and current affairs.” You might repurpose these lively pieces of medieval art for such twenty-first-century topics as clubbing, online shopping, or the COVID-19 pandemic.

At the top of this post appears an image from 1327, originally created for a book of miracles King Charles IV ordered for his queen. As KB explains, it offers “a warning of what can happen if you don’t learn your prayers properly.” Below that is “a sort of Mediaeval cartoon” from 1183 about the techniques involved in properly slaughtering a pig. And just above, we see what happened when “the Kenite Jael lured the leader of the army, Sisera, into her tent. Sisera had been violently oppressing the Kenites for 20 years. While he slept, she whacked a tent peg straight through his head.” Though created for a picture Bible 592 years ago, this picture surely has potential for transposition into commentary on the very different perils of life in the twenty-twenties. But when you deploy it as a meme, you can do so in the knowledge that even your medieval forebears would have known that feel.

Related content:

Why Butt Trumpets & Other Bizarre Images Appeared in Illuminated Medieval Manuscripts

Why Knights Fought Snails in Illuminated Medieval Manuscripts

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Watch Stevie Wonder’s Amazing Drum Solo, and See Why He May Be the “Greatest Drummer of Our Time”

When Prince passed away, many a non-Prince fan suddenly found out that the man was not only a brilliant songwriter, singer, dancer, guitarist, pianist, stylist, and superstar, but that he was also a virtual one-man band in the studio, able to play almost any instrument, in exactly the way he wanted it played. Prince fans knew this, as do fans of the musician who made Songs in the Key of Life — or what Prince called the greatest album ever recorded. And if Prince were here, he would agree: Stevie Wonder deserves more appreciation for his multi-musicianship while he’s still with us.

Yes, of course, we know him for his “staggering songwriting and vocal skills,” writes PC Muñoz at Drum! magazine, for his “prowess as a formidable, inventive keyboardist (and pop music synthesizer pioneer)” and “his virtuoso-level skills on harmonica.”

But do we know Stevie Wonder as a drummer? Well, “newsflash for those who didn’t know,” Muñoz announces: “Stevie Wonder also happens to be one badass drummer.” (In fact, his very first gig, at 8 years old, was on the drums.) Not that he hasn’t received his just due from fellow musicians, far from it.

Eric Clapton called Wonder “the greatest drummer of our time” in 1974 — “hefty praise” (and maybe a bit of a swipe), wrote music journalist Eric Sandler, “coming from a man who played with Ginger Baker.” See a demonstration of Wonder’s formidable feel and groove behind the kit in the drum solo at the top of the post. But, of course, you’ve already heard his drumming — all, or most, of your life perhaps — on his albums, including most every track on Talking Book, Songs in the Key of Life, and Innervisions — songs like “Superstition,” “Higher Ground,” “Living for the City” … all Stevie.

“I grew up practicing to Stevie Wonder’s music,” drummer Eric Carnes tells Muñoz, “but I actually didn’t know he was often the drummer on his own stuff. Until I was in my twenties.” Carnes goes on to describe the hallmarks of Wonder’s style: “very relaxed – not so crisp and not so metronomic. He’s using different parts of the stick at different times, and his hi-hat parts change throughout the song. A lot of times, each chorus in a given song is played slightly differently, too. He escalates a song over a long period of time, really growing the whole piece, instead of topping out early; it gives the music somewhere to go.”

Bill Janovitz of the band Buffalo Tom — in a very thorough paean to Songs in the Key of Life – points to the “innate sense of groove in his drumming.… There is a musical inventiveness that might stem from being a well-rounded multi-instrumentalist, as opposed to someone who strictly defines themselves as a drummer.”

In his appreciation of Wonder’s drumming at Slate, Seth Stevenson also highlights Wonder’s “expressiveness.… No two measures sound the same.” He offers a mini best-of roundup of Wonder’s recorded drumming moments:

My favorite Wonder drum track comes on ‘Too High,’ the first song on Innervisions. Subtle snare rolls, sudden tom-tom tumbles, jazzy ride-cymbal swings – they’re all scrumptious and all in the greater service of the song. This is not the approach of a hired drummer attempting to carve out his own terrain. It’s the work of a multi-instrumentalist composer who fits his vision for each part into an interlocking whole.

Stevenson and Janovitz speak to a thread in so many discussions of “virtuoso” musicians: composers who are also musical prodigies have ways of playing instruments in an idiom only they can understand. One imagines that if we had recordings of Mozart or Bach – both prodigious multi-instrumentalists from very young ages – we would hear classical instruments played in ways we’ve never heard them played before. The magic of recording — and Stevie Wonder’s recordings especially — means we can hear the drums on his songs exactly as he heard, and played, them, and exactly as he wanted them played.

Related Content:

Catch Stevie Wonder, Ages 12–16, in His Earliest TV Performances

See Stevie Wonder Play “Superstition” and Banter with Grover on Sesame Street in 1973

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...