Ouch!

What history nerd doesn’t thrill to Thomas Edison speaking to us from beyond the grave in a 50th anniversary repeat of his groundbreaking 1877 spoken word recording of (those hoping for loftier stuff should dial it down now) Mary Had a Little Lamb?

The original represents the first time a recorded human voice was successfully captured and played back. We live in hope that the fragile tinfoil sheet on which it was recorded will turn up in someone’s attic someday.

Apparently Edison got it in the can on the first take. The great inventor later reminisced that he “was never so taken aback” in his life as when he first heard his own voice, issuing forth from the phonograph into which he’d so recently shouted the famous nursery rhyme:

Everybody was astonished. I was always afraid of things that worked the first time.

His achievement was a game changer, obviously, but it wasn’t the first time human speech was successfully recorded, as Kings and Things clarifies in the above video.

That honor goes to Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville, whose phonautograph, patented in 1857, transcribed vocal sounds as wave forms etched onto lampblack-coated paper, wood, or glass.

Edison’s plans for his invention hinged on its ability to reproduce sound in ways that would be familiar and of service to the listening public. A sampling:

Léon Scott’s vision for his phonautograph reflects his preoccupation with the science of sound.

A professional typesetter, with an interest in shorthand, he conceived of the phonautograph as an artificial ear capable of reproducing every hiccup and quirk of pronunciation far more faithfully than a stenographer ever could. It was, in the words of audio historian Patrick Feaster, the “ultimate speech-to-text machine.”

As he told NPR’s Talk of the Nation, Léon Scott was driven to “get sounds down on paper where he could look at them and study them:”

…in terms of what we’re talking about here visually, anybody who’s ever used audio editing software should have a pretty good idea of what we’re talking about here, that kind of wavy line that you see on your screen that somehow corresponds to a sound file that you’re working with…He was hoping people would learn to read those squiggles and not just get the words out of them.

Although Léon Scott managed to sell a few phonautographs to scientific laboratories, the general public took little note of his invention. He was pained by the global acclaim that greeted Edison’s phonograph 21 years later, fearing that his own name would be lost to history.

His fear was not unfounded, though as Conan O’Brien, of all people, mused, “eventually, all our graves go unattended.”

But Léon Scott got a second act, as did several unidentified long-dead humans whose voices he had recorded, when Dr. Feaster and his First Sounds colleague David Giovannoni converted some phonautograms to playable digital audio files using non-contact optical-scanning technology from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Dr. Feaster describes the eerie experience of listening to the cleaned-up spoken word tracks after a long night of tweaking file speeds, using Léon Scott’s phonautograms of tuning forks as his guide:

I’m a sound recording historian, so hearing a voice from 100 years ago is no real surprise for me. But sitting there, I was just kind of stunned to be thinking, now I’m suddenly at last listening to a performance of vocal music made in France before the American Civil War. That was just a stunning thing, feeling like a ghost is trying to sing to me through that static.

Scanning technology also allowed historians to create playable digital files of fragile foil recordings made on Edison devices, like the St. Louis Tinfoil , made by writer and early adopter Thomas Mason in the summer of 1878, as a way of showing off his new-fangled phonograph, purchased for the whopping sum of $95.

The British Library’s Tinfoil Recording is thought to be the earliest in existence. It features an as-yet unidentified woman, who may or may not be quoting from social theorist Harriet Martineau… this garbled ghost is exceptionally difficult to pin down.

Far easier to decipher are the 1889 recordings of Prussian Field Marshall Helmuth Von Multke, who was born in 1800, the last year of the 18th century, making his the earliest-born recorded voice in audio history.

The nonagenarian recites from Hamlet and Faust, and congratulates Edison on his astonishing invention:

This phonograph makes it possible for a man who has already long rested in the grave once again to raise his voice and greet the present.

Related Content

Suzanne Vega, “The Mother of the MP3,” Records “Tom’s Diner” with the Edison Cylinder

A Beer Bottle Gets Turned Into a 19th Century Edison Cylinder and Plays Fine Music

400,000+ Sound Recordings Made Before 1923 Have Entered the Public Domain

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Before electronic amplification, instrument makers and musicians had to find newer and better ways to make themselves heard among ensembles and orchestras and above the din of crowds. Many of the acoustic instruments we’re familiar with today—guitars, cellos, violas, etc.—are the result of hundreds of years of experimentation focused on solving just that problem. These hollow wooden resonance chambers amplify the sound of the strings, but that sound must escape, hence the circular sound hole under the strings of an acoustic guitar and the f‑holes on either side of a violin.

I’ve often wondered about this particular shape and assumed it was simply an affected holdover from the Renaissance. While it’s true f‑holes date from the Renaissance, they are much more than ornamental; their design—whether arrived at by accident or by conscious intent—has had remarkable staying power for very good reason.

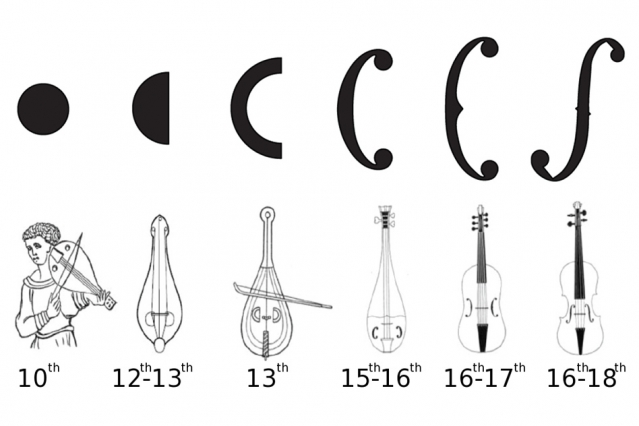

As acoustician Nicholas Makris and his colleagues at MIT announced in a study published by the Royal Society, a violin’s f‑holes serve as the perfect means of delivering its powerful acoustic sound. F‑holes have “twice the sonic power,” The Economist reports, “of the circular holes of the fithele” (the violin’s 10th century ancestor and origin of the word “fiddle”).

The evolutionary path of this elegant innovation—Clive Thompson at Boing Boing demonstrates with a color-coded chart—takes us from those original round holes, to a half-moon, then to variously-elaborated c‑shapes, and finally to the f‑hole. That slow historical development casts doubt on the theory in the above video, which argues that the 16th-century Amati family of violin makers arrived at the shape by peeling a clementine, perhaps, and placing flat the surface area of the sphere. But it’s an intriguing possibility nonetheless.

Instead, through an “analysis of 470 instruments… made between 1560 and 1750,” Makris, his co-authors, and violin maker Roman Barnas discovered, writes The Economist, that the “change was gradual—and consistent.” As in biology, so in instrument design: the f‑holes arose from “natural mutation,” writes Jennifer Chu at MIT News, “or in this case, craftsmanship error.” Makers inevitably created imperfect copies of other instruments. Once violin makers like the famed Amati, Stradivari, and Guarneri families arrived at the f‑hole, however, they found they had a superior shape, and “they definitely knew what was a better instrument to replicate,” says Makris. Whether or not those master craftsmen understood the mathematical principles of the f‑hole, we cannot say.

What Makris and his team found is a relationship between “the linear proportionality of conductance” and “sound hole perimeter length.” In other words, the more elongated the sound hole, the more sound can escape from the violin. “What’s more,” Chu adds, “an elongated sound hole takes up little space on the violin, while still producing a full sound—a design that the researchers found to be more power-efficient” than previous sound holes. “Only at the very end of the period” between the 16th and the 18th centuries, The Economist writes, “might a deliberate change have been made” to violin design, “as the holes suddenly get longer.” But it appears that at this point, the evolution of the violin had arrived at an “optimal result.” Attempts in the 19th century to “fiddle further with the f‑holes’ designs actually served to make things worse, and did not endure.”

To read the mathematical demonstrations of the f‑hole’s superior “conductance,” see Makris and his co-authors’ published paper here. And to see how a contemporary violin maker cuts the instrument’s f‑holes, see a careful demonstration in the video above.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2016.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

On the evening of January 12, 1971, CBS viewers across the United States sat down to a brand new sitcom preceded by a highly unusual disclaimer. The program they were about to see, it declared, “seeks to throw a humorous spotlight on our frailties, prejudices, and concerns. By making them a source of laughter, we hope to show — in a mature fashion — just how absurd they are.” Thereafter commenced the very first episode of All in the Family, which would go on, over nine full seasons, to define American television in the nineteen-seventies. It did so not just by daring to find comedy in the issues of the day — the Vietnam War, the generation gap, women’s lib, race relations, homosexuality — but also by spawning a variety of other major sitcoms like Maude, The Jeffersons, and Good Times.

Even if you didn’t live through the seventies, you’ve probably heard of these shows. Now you can watch full episodes on the official Youtube channel of Norman Lear, the television writer and producer involved in the creation of all of them and many others besides.

If you’ve ever seen Sanford and Son, Fernwood 2 Night, Diff’rent Strokes, or One Day at a Time (or if you happened to catch such short-lived obscurities as Hanging In, a.k.a. Pablo, and Sunday Dinner), you’ve seen one of his productions. His death this week at the age of 101 has provided the occasion to acquaint or reacquaint ourselves with Archie and Edith Bunker, George and Louise Jefferson, Florida and James Evans, and all the other characters from what we might now call the “Norman Lear multiverse.”

The best place to start is with the premiere of All in the Family, which introduces the Bunker clan and the central conflict of their household: that between boisterously prejudiced working-class patriarch Archie Bunker and his bleeding-heart baby-boomer son-in-law Michael “Meathead” Stivic. Later episodes introduce such secondary characters as Edith Bunker’s strong-willed cousin Maude Findlay, who went on to star in her own eponymous series the following year, and the Bunkers’ enterprising black next-door neighbors the Jeffersons, who themselves “moved on up” in 1975. (So far did the televisual Learverse eventually expand that Good Times and Checking In were built around the characters of Maude and the Jeffersons’ maids.)

An outspoken proponent of liberal causes, Lear probably wouldn’t have denied using his television work to influence public opinion on the issues that concerned him. Yet at their best, his shows didn’t reduce themselves to political morality plays, showing an awareness that the Archie Bunkers of the world weren’t always in the wrong and the Meatheads weren’t always in the right. By twenty-first-century standards, the jokes volleyed back and forth in All in the Family or The Jeffersons may seem blunt, not least when they employ terms now regarded as unspeakable on mainstream television. But they also have the forthrightness to go wherever the humor of the situation — that is to say, the truth of the situation — dictates, an uncommon quality among even the most acclaimed comedies this half-century later. Watch complete episodes of Norman Lear shows here.

Related content:

Watch Mad Magazine’s Edgy, Never-Aired TV Special (1974)

Watch Between Time and Timbuktu, an Obscure TV Gem Based on the Work of Kurt Vonnegut

Watch the Opening Credits of an Imaginary 70s Cop Show Starring Samuel Beckett

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

You’re busy. You don’t have much time to figure out the deal with Large Language Models (aka LLMs). But you have some curiosity. Enter Andrej Karpathy and his presentation, “A Busy Person’s Introduction to Large Language Models.” It’s a one-hour tutorial that explains “the core technical component behind systems like ChatGPT, Claude, and Bard.” Designed for a general audience, the video explains what Large Language Models (LLMs) are, and where Karpathy sees them going. Andrej knows what he’s talking about. He currently works for OpenAI (the maker of ChatGPT), and, before that, he served as the director of artificial intelligence at Tesla.

As one YouTube commenter put it, “Andrej is hands-down one of the best ML [Machine Learning] educators out there.” At Stanford, he was the primary instructor for the first deep learning class, which has become one of the largest courses at the university. Enjoy.

Related Content

Generative AI for Everyone: A Free Course from AI Pioneer Andrew Ng

Neural Networks for Machine Learning: A Free Online Course Taught by Geoffrey Hinton

Not quite a century ago, Shanghai was known as “the Paris of the East.” (Or it became one of the cities to enjoy that reputation, at any rate.) Today, you can catch a high-speed train in Shanghai and, just an hour later, arrive in a place that has made a much more literal bid for that title: Tianducheng, a district modeled directly on the French capital, complete with not entirely unconvincing faux-Haussmannian apartment buildings and boulevards. Struggling to attract residents in the years after its construction on farmland at the outskirts of Hangzhou in 2007, Tianducheng soon came to be regarded as one of China’s over-ambitious ghost towns.

Bizarre as it may seem to those unfamiliar with recent trends in Chinese city-building, Tianducheng actually belongs to a kind of imitative tradition. “On the outskirts of Beijing, a replica of Jackson Hole, Wyoming, is outfitted with cowboys and a Route 66,” writes National Geographic’s Gulnaz Khan.

“Red telephone booths, pubs, and statues of Winston Churchill pepper the corridors of Shanghai’s Thames Town. The city of Fuzhou is constructing a replica of Stratford-upon-Avon in tribute to Shakespeare.” To get a sense of how Tianducheng fares today, have a look at “I Explored China’s Failed $1 Billion Copy of Paris,” the new video from Youtube travel channel Yes Theory.

The group of friends making this trip includes one Frenchman, who admits to a certain sense of familiarity in the built environment of Tianducheng, and even seems genuinely stunned by his first glimpse of its one-third-scale version of the Eiffel Tower. (It surely pleases visiting Parisians to see that the developers haven’t also built their own Tour Montparnasse.) But apart from Chinese couples in search of a wedding-photo spot, this ersatz Eiffel Tower doesn’t seem to draw many visitors, or at least not during the day. As Yes Theory’s travelers discover, the neighborhood doesn’t come alive until the evening, when such locals as have settled in Tianducheng come out and enjoy their unusual cityscape. The street life of this Champs-Élysées is a far cry indeed from the real one — but in its way, it also looks like a lot more fun.

Related content:

A 5‑Hour Walking Tour of Paris and Its Famous Streets, Monuments & Parks

A 3D Animation Reveals What Paris Looked Like When It Was a Roman Town

The Sights & Sounds of 18th Century Paris Get Recreated with 3D Audio and Animation

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

New Yorkers have a variety of sayings about how they want nothing to do with nature, just as nature wants nothing to do with them. As a counterpoint, one might adduce Central Park, whose 843 acres of trees, grass, and water have occupied the middle of Manhattan for a century and a half now. Yet that “most famous city park in the world,” as veteran New York architect Michael Wyetzner puts it in the Architectural Digest video above, is both nature and not. Though Central Park may feel as if it has existed since time immemorial, organically thriving in its space long before the towers that surround it, few large urban spaces had ever been so deliberately conceived.

In the video, Wyetzner (previously featured here on Open Culture for his explanations of New York apartments, subway stations, and bridges, as well as individual works of architecture like Penn Station and the Chrysler Building) shows us several spots in Central Park that reveal the choices that went into its design and construction.

Many were already present in landscape architects Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux’s original plan, which they submitted to an open design competition in 1857. Of all the entries, only theirs refused to let the park be cut apart by transverse roads, opting instead to round automobile traffic underground and preserve a continuous experience of “nature” for visitors. (If only more recent urban parks could have kept its example in mind.)

Central Park would be welcome even if it were just a big of expanse of trees, grass, and water. But it also contains many distinctive built structures, such as the much-photographed mall leading to Bethesda Terrace, the “second-oldest cast-iron bridge in the United States,” the dairy that once provided fresh milk to New York’s children, and Belvedere Castle. That last is built at three-quarters scale, “which makes it appear further away than it actually is, and gives it this sort of magical fairy-tale quality,” the same trick that the builders of Disneyland would employ intensively about a century later. But the priorities of Walt Disney and his collaborators differed from the designers of Central Park, who, as Vaux once said, put “nature first, second, and third — architecture after a while.” If a mutually beneficial deal could be struck between those two phenomena anywhere, surely that place is New York City.

Related content:

The Lost Neighborhood Buried Under New York City’s Central Park

An Architect Breaks Down the Design of New York City Subway Stations, from the Oldest to Newest

An Immersive Architectural Tour of New York City’s Iconic Grand Central Terminal

Architect Breaks Down Five of the Most Iconic New York City Apartments

A Whirlwind Architectural Tour of the New York Public Library — “Hidden Details” and All

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Image via Wikimedia Commons

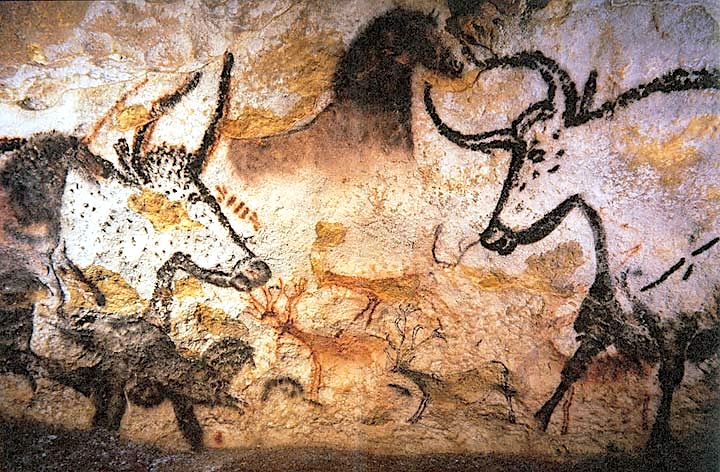

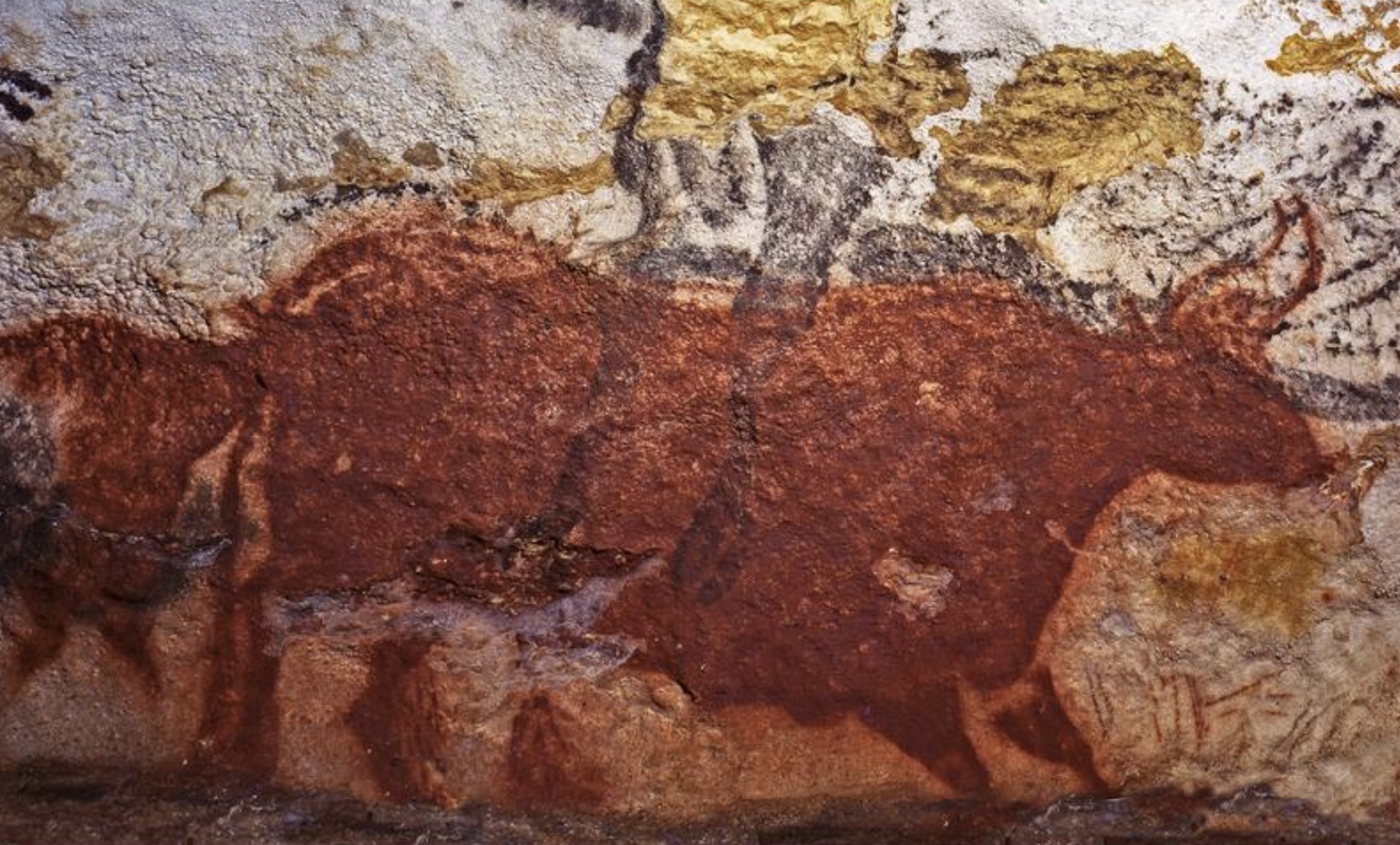

The Lascaux Caves enjoyed a quiet existence for some 17,000 years.

Then came the summer of 1940, when four teens investigated what seemed to be a fox’s den on a hill near Montignac, hoping it might lead to an underground passageway of local legend.

Once inside, they discovered the paintings that have intrigued us ever since, expanding our understanding of prehistoric art and human origins, and causing us to speculate on things we’ll never have an answer to.

The boys’ teacher reached out to several prehistorians, who authenticated the figures, arranged for them to be photographed and sketched, and collected a number of bone and flint artifacts from the caves’ floors.

By 1948, excavations and artificial lights rendered the caves accessible to visitors, who arrived in droves — as many as 1,800 in a single day.

Less than 20 years later, The Collector’s Rosie Lesso writes, the caves were in crisis, and permanently closed to tourism:

…the heat, humidity and carbon dioxide of all those people crammed into the dark and airless cave was causing an imbalance in the cave’s natural ecosystem, leading to the overgrowth of molds and funguses that threatened to obliterate the prehistoric paintings.

The lights that had helped visitors get an eyeful of the paintings caused fading and discoloration that threatened their very existence.

Declaring this major attraction off limits was the right move, and those who make the journey to the area won’t leave entirely disappointed. Lascaux IV, a painstaking replica that opened to the public in 2016, offers even more verisimilitude than the previous model, 1983’s Lascaux II.

A handful of researchers and maintenance workers are still permitted inside the actual caves, now a UNESCO World Heritage site, but human presence is limited to an annual total of 800 hours, and everyone must be properly outfitted with sterile white overalls, plastic head coverings, latex gloves, double shoe covers, and LED forehead lamps with which to view the paintings.

The rest of us rabble can get a healthy virtual taste of these visitors’ experience thanks to the digital Lascaux collection that the National Archeology Museum created for the Ministry of Culture.

An interactive tour offers close-up views of the famous paintings, with titles to orient the viewer as to the particulars of what and where — for example “red cow followed by her calf” in the Hall of the Bulls.

Click the button in the lower left for a more in-depth expert description of the element being depicted:

The flat red color used for the silhouette is of a uniformity that is seldom attained, which implies a repeated gesture starting from the same point, with complementary angles of projection of pigments. The outlines have been created with a stencil, and only the hindquarters, horns and the line of the back have been laid down with a brush…The fact that the artist used the same pigment for both figures without any pictorial transition between them indicates that the fusion of the two silhouettes was intentional, indicative of the connection between the calf and its mother. This duo was born of the same gesture, and the image of the offspring is merely the graphic extension of that of its mother.

The interactive virtual tour is further complimented by a trove of historic photographs and interviews, geological context, conservation updates and anthropological interpretations suggesting the paintings had a function well beyond visual art.

Begin your virtual interactive visit to the Lascaux Cave here.

Related Content

Was a 32,000-Year-Old Cave Painting the Earliest Form of Cinema?

Algerian Cave Paintings Suggest Humans Did Magic Mushrooms 9,000 Years Ago

40,000-Year-Old Symbols Found in Caves Worldwide May Be the Earliest Written Language

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

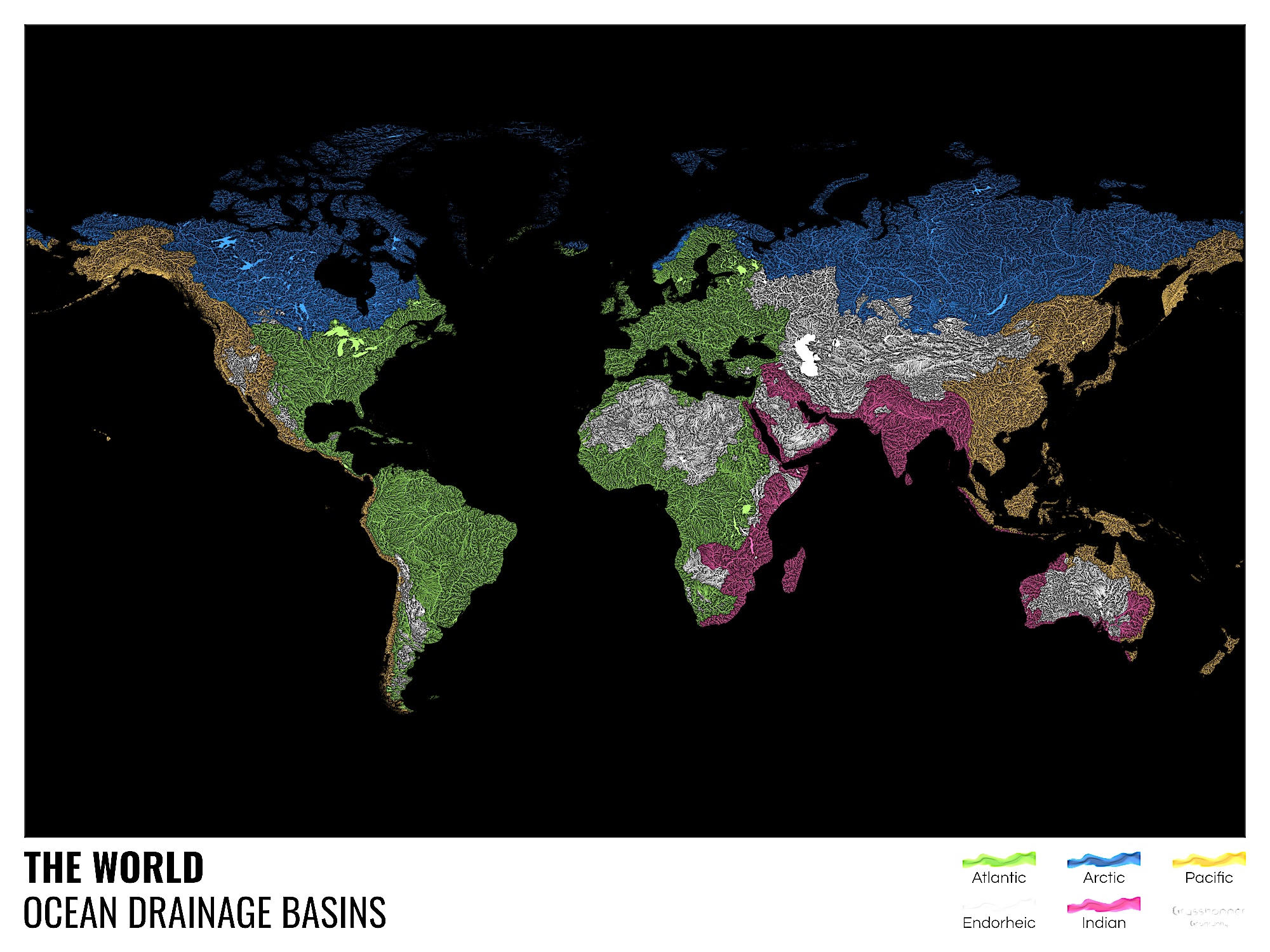

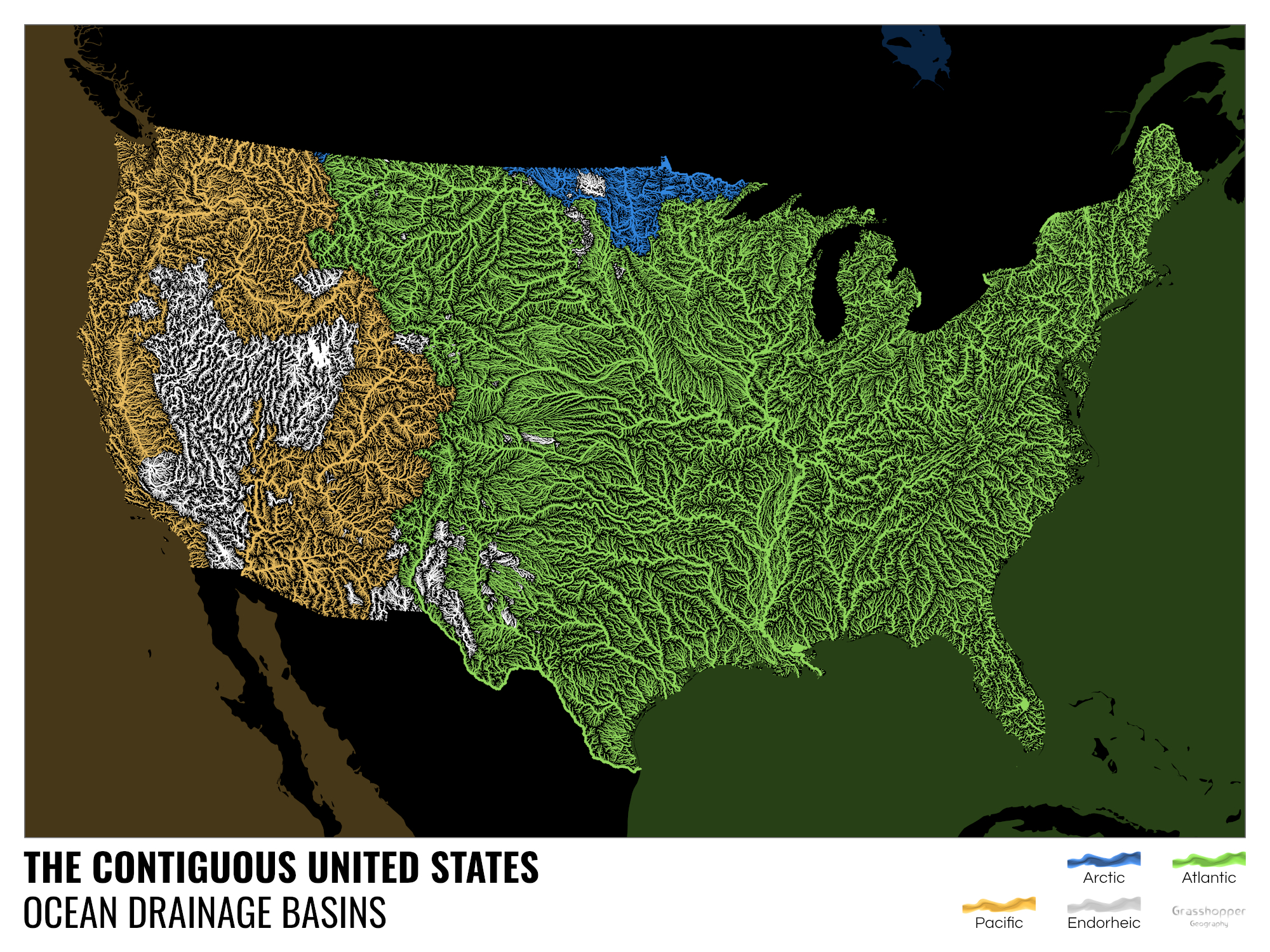

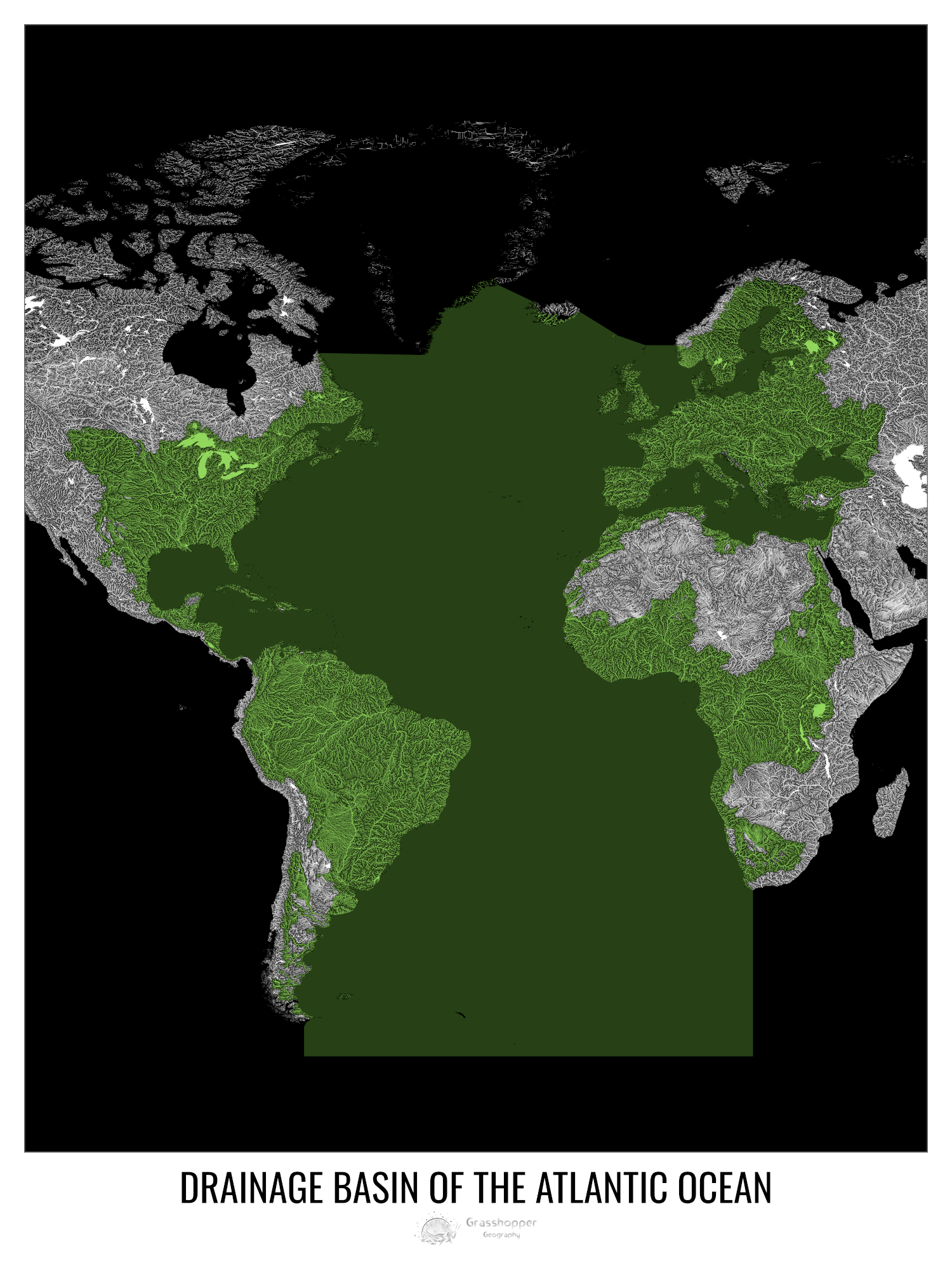

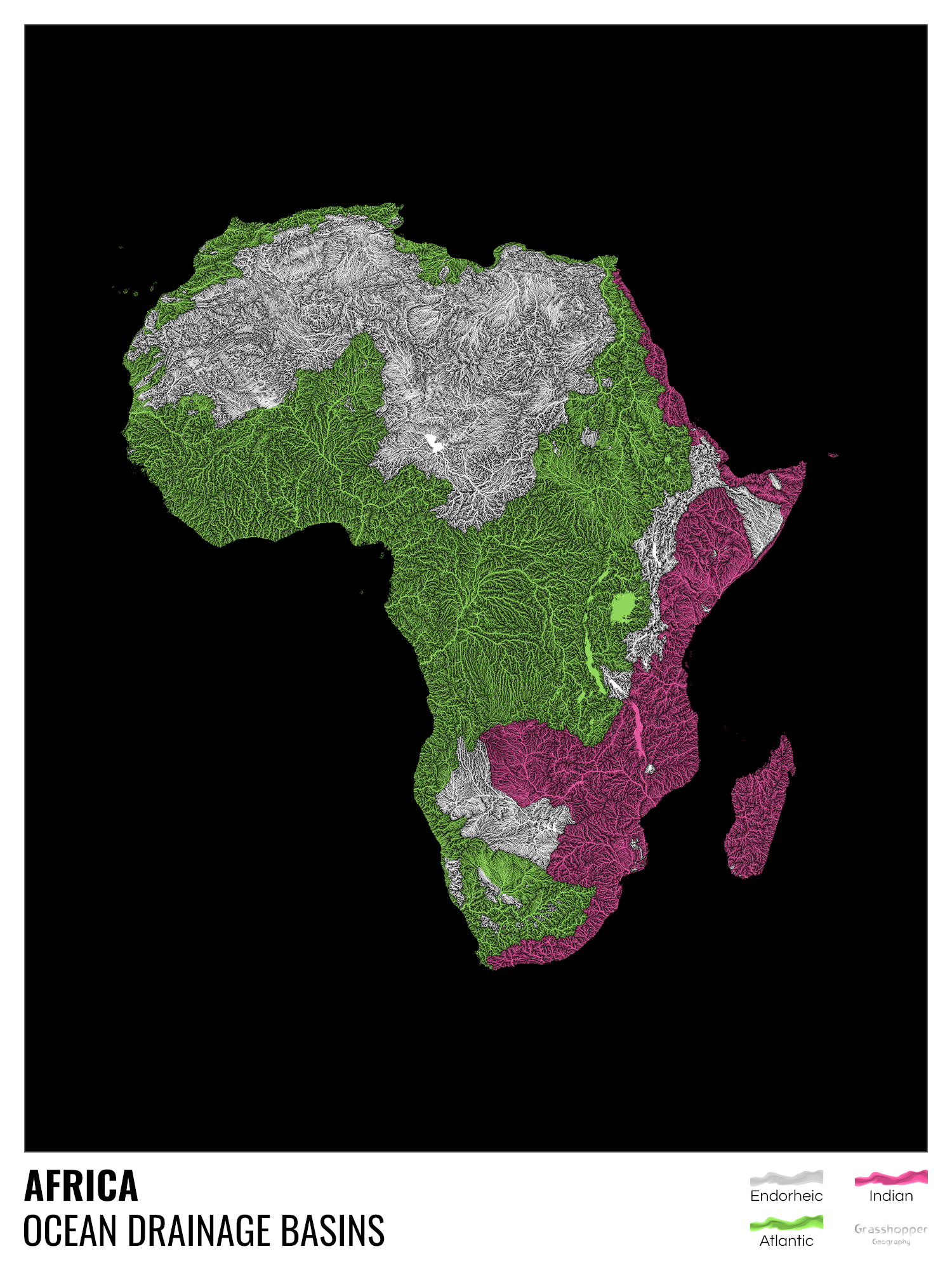

Even if you’ve never traveled the seas, you’ve surely known at least a few rivers in your time. And though you must be conscious of the fact that all of those rivers run, ultimately, to the sea, you may not have spent much time contemplating it. Now, thanks to the work of mapmaker and data analyst Robert Szucs, you won’t be able to come upon at a river without considering the particular sea into which it flows. He’s created what he calls “the first ever map of the world’s rivers divided into ocean drainage basins,” which appears just above.

This world map “shows, in different colors, all the rivers that flow into the Atlantic, Arctic, Indian or Pacific oceans, plus endorheic river basins which never reach the coast, mostly due to drying up in desert areas.”

Szucs has also broken it down into “a set of 43 maps in this style for different countries, states and continents,” all of them available to download (and to purchase as large-format posters) from his web site Grasshopper Geography.

We previously featured Szucs here on Open Culture back in 2017, when he published a river-and-stream-visualizing map of the United States made according to a similarly colorful and informative scheme. Examining that work of information design gave me a richer context in which to imagine the rivers around which I grew up in Washington State — the Sammamish, the Snoqualmie, the Columbia — as well as a clearer sense of just how much the United States’ larger, much more complex waterway network must have contributed to the development of the country as a whole.

Of course, having lived the better part of a decade in South Korea, I’ve lately had less reason to consider those particular geographical subjects. But Szucs’ new global ocean drainage maps have brought related ones to mind: it will henceforth be a rare day when I ride a train across the Han River (one of the more sublime everyday sights Seoul has to offer) and don’t imagine it making its way out to the Pacific — the very same Pacific that was the destination of all those rivers of my west-coast American youth. Oceanically speaking, even a move across the world doesn’t take you quite as far as it seems.

Related content:

All the Rivers & Streams in the U.S. Shown in Rainbow Colors: A Data Visualization to Behold

That Time When the Mediterranean Sea Dried Up & Disappeared: Animations Show How It Happened

A Radical Map Puts the Oceans — Not Land — at the Center of Planet Earth (1942)

Tour the Amazon with Google Street View; No Passport Needed

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

We’re taking you on a wistful trip down memory lane. Above, Shane MacGowan and Sinéad O’Connor perform “Haunted” on the British music show, The White Room. Originally recorded in 1986 with Cait O’Riordan on vocals, “Haunted” got a second lease on life in 1995 when MacGowan and O’Connor cut a new version, combining her ethereal vocals with his inimitable songwriting and whiskey-soaked voice. Below, they both appear in an interview recorded during the same period.

The two Irish musicians first met in London during the 1980s, starting a friendship that would have its ups and downs. Their collaboration on “Haunted” marked a high point. Then, in 1999, O’Connor called the police when she found MacGowan doing heroin at home. Angered at first, MacGowan later credited the intervention with helping him kick his habit. When Sinéad gave birth to her third child in 2004, she named him Shane, in honor of her friend.

MacGowan and O’Connor both died this year, just months apart from one another. As you watch their duet, you can’t help but feel the sand running through the hourglass. It leaves you feeling grateful for what we had, and sad for what we have lost. May they rest in peace.

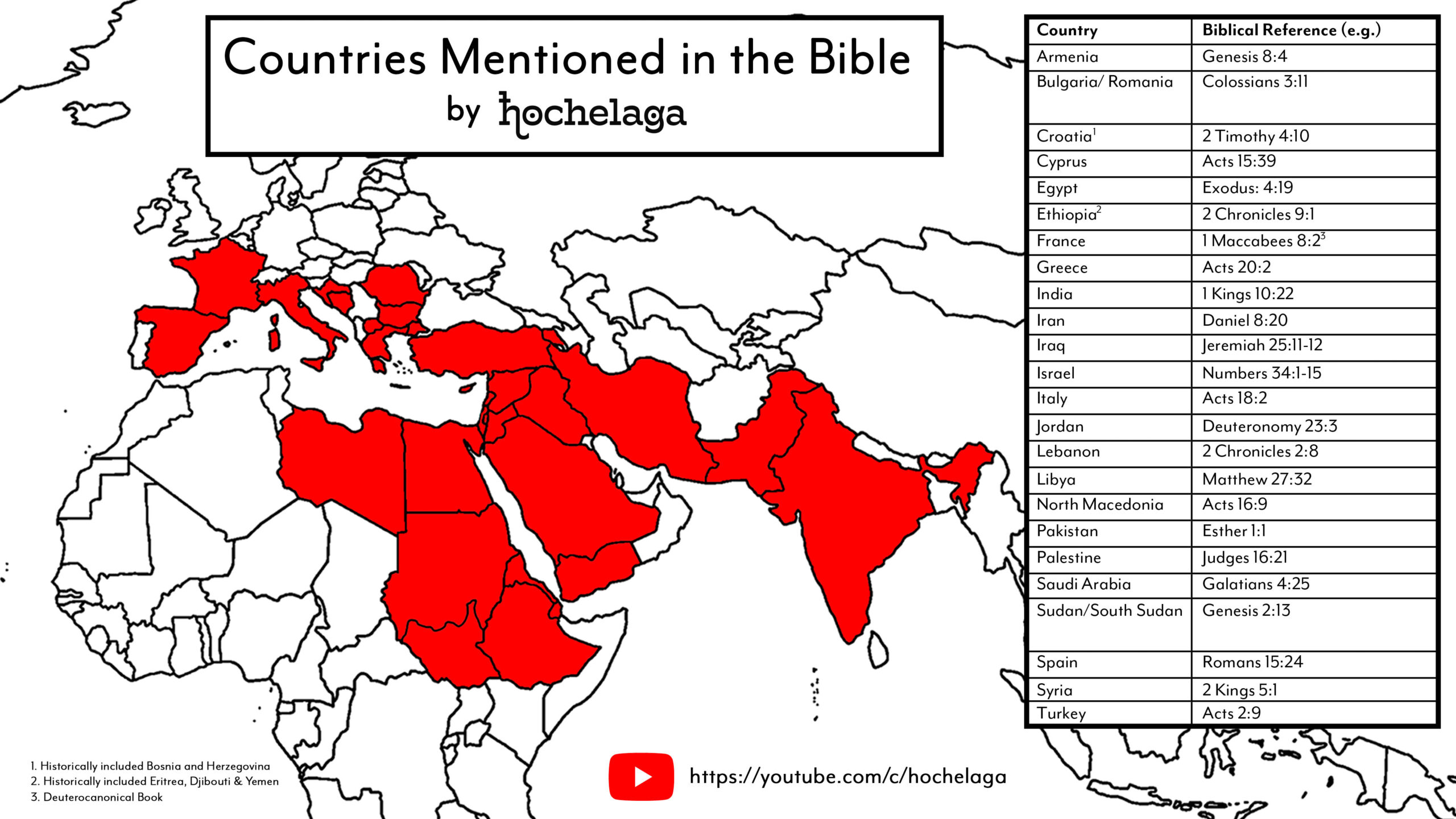

“For most of the last two thousand years, the Bible has been virtually the only history book used in Western civilization,” writes Isaac Asimov in his Guide to the Bible. “Even today, it remains the most popular, and its view of ancient history is still more widely and commonly known than is that of any other.” As a result, “millions of people today know of Nebuchadnezzar, and have never heard of Pericles, simply because Nebuchadnezzar is mentioned prominently in the Bible and Pericles is never mentioned at all.” That same disproportionate recognition is accorded to “minor Egyptian pharaohs” like Shishak and Necho, “people whose very existence is doubtful” like Nimrod and the Queen of Sheba, and “small towns in Canaan, such as Shechem and Bethel.”

Asimov notes that “only that is known about such places as happens to be mentioned in the Bible. Ecbatana, the capital of the Median Empire, is remembered in connection with the story of Tobit, but its earlier and later history are dim indeed to most people, who might be surprised to know that it still exists today as a large provincial capital in the modern nation of Iran.” In the video from Hochelaga above, we learn that Iran, then called Persia, is celebrated in the Bible “for ending the Jewish exile and returning Israel to its homeland. The Book of Usaiah gives a special shout-out to its King, Cyrus the Great: he is given the title ‘anointed one,’ or ‘messiah.’ ”

Though “Persia has played a huge role in the history of the region, and at a time was one of the largest empires of its day,” it’s just one of the surprisingly many lands to receive Biblical acknowledgement. As Hochelaga creator Tommy Trelawny makes clear, “when the Bible was written, the countries as we know them today didn’t even exist.” But though the concept of the modern nation-state hadn’t yet come into being, the places that would give rise to a fair few of the nation-states in the twenty-first century certainly had: “shout-out to Egypt, Lebanon, Israel, Persia, Cyprus, Greece, Italy, and Spain, that still exist today, or at least go by the names that appear in the Bible.”

You may notice, Trelawny adds, that “many of these exotic lands are mentioned in the story of King Solomon’s temple, and how precious raw materials were imported from faraway places, from the strongest Lebanese cedars to the finest Indian ivories.” It hardly matters “whether King Solomon was even real; we know these geographical regions exist today, and that Biblical writers seemed to know of them as well.” As depicted in the Bible or other sources, the ancient world can seem scarcely recognizable to us. But if we make the necessary adjustments to our perspective, we can see a process of globalization not dissimilar to what we see in our own societies — whose fascination with distant lands and expensive luxuries seems hardly to have diminished over the millennia.

Related content:

Christianity Through Its Scriptures: A Free Course from Harvard University

Introduction to the Old Testament: A Free Yale Course

Introduction to New Testament History and Literature: A Free Yale Course

Ancient Israel: A Free Course from NYU

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.