Doric, Ionic, Corinthian: these, as practically everyone who went through school in the West somehow remembers, are the three varieties of classical column. We may still recall them, more specifically, as representing the three ancient Greek architectural styles. But as ancient-history YouTuber Garrett Ryan points out in the new Told in Stone video above, only Doric and Ionic columns belong fully to ancient Greece; what we think of when we think of Corinthian columns were developed more in the civilization of ancient Rome. The context is an explanation of how the ancient Greeks built their temples, one of the characteristics of their design process being the use of columns aplenty.

It’s one thing to hear about Greek columns in the classroom, and quite another to walk amid them in person. That, perhaps, is why Ryan delivers the opening of his video perched upon the ruins of what’s known as Temple C. Having once stood proudly in Selinus, a city belonging to Magna Graecia (Greek-speaking areas of Italy), it now constitutes one of the prime tourist attractions for antiquity-minded visitors to modern-day Sicily.

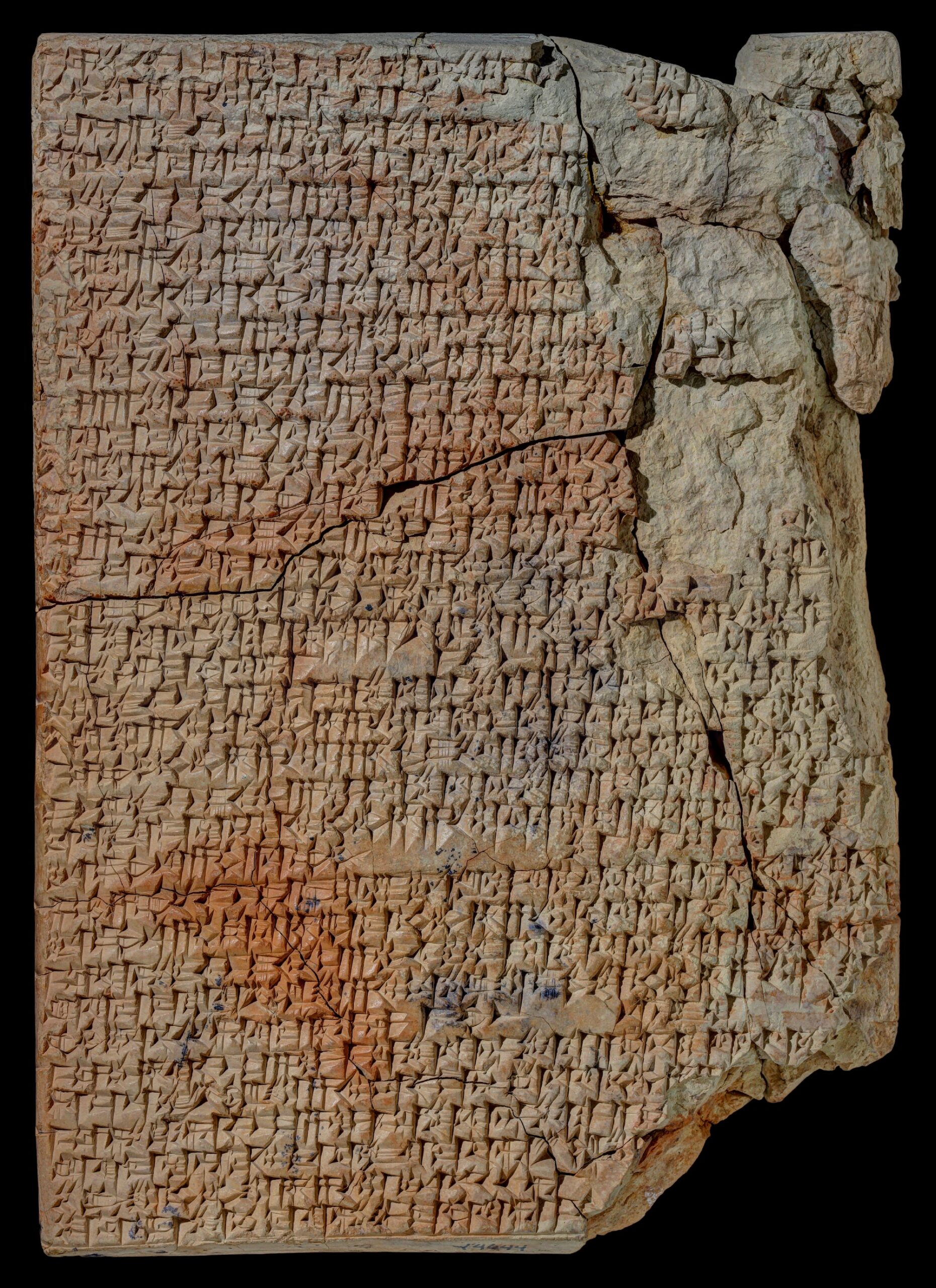

Though his channel may be called Told in Stone, Ryan begins his brief history of the Greek temple before that hardy material had even come into use for these purposes. At first, the Greeks fashioned the homes of their gods out of mud brick, with thatched roofs and wooden porches; only from the seventh century BC, “probably inspired by contact with Egypt,” did they start building them to last.

Or they built them to last as long as could be expected, in any case, given the nature of the materials available in the ancient world and the millennia that have passed since then. Take the Temple of Apollo at the Sanctuary of Didyma in modern-day Turkey, which history-and-architecture YouTuber Manuel Bravo pays a visit in the video just above. It may not look as if the nearly 2400 years since its never-technically-completed construction began have been kind, but it’s nevertheless one of the better-preserved temples from ancient Greek civilization in existence (not to mention the largest). Even in its ruined state, it gives what Bravo describes as the impression of — or at least, in its heyday, having been — “a forest of huge columns,” a built version of “the sacred forests that Greeks used to consecrate to the gods.” They’re Ionic columns, in case you were wondering, but don’t sweat it; there won’t be a quiz.

Related content:

A 3D Model Reveals What the Parthenon and Its Interior Looked Like 2,500 Years Ago

How the Parthenon Marbles Ended Up In The British Museum

The History of Ancient Greece in 18 Minutes: A Brisk Primer Narrated by Brian Cox

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.