If you spend any time at all on social media, you’ll have glimpsed the work of DALL‑E, OpenAI’s now-famous artificial-intelligence engine that generate images from simple text descriptions. A velociraptor dressed like Travis Bickle, American Gothic starring Homer and Marge Simpson, that astronaut riding a horse on the moon: like any the-future-is-now moment, especially in recent years on the internet, DALL-E’s rise has produced a host of artifacts as impressive as they are ridiculous. Now you can try to top them in both of those dimensions yourself, since not just DALL‑E but the new, improved, higher-resolution DALL‑E 2 has just opened for public use.

“How do you use DALL‑E 2?” You might well ask, and Creative Bloq has a guide for you. “The tool generates art based on text prompts,” it explains. “On the face of it, that couldn’t be more simple. Once you’ve completed the DALL‑E 2 sign up to open an account, you use the program in your browser on the DALL‑E 2 website. You type in a description of what you want, and DALL‑E will create the image.”

Of course, some prompts produce more visually interesting results than others. The guide recommends that you consult the DALL‑E 2 prompt book, which gets into how best to phrase your descriptions in order to inspire the richest combinations of subject, texture, style, and form.

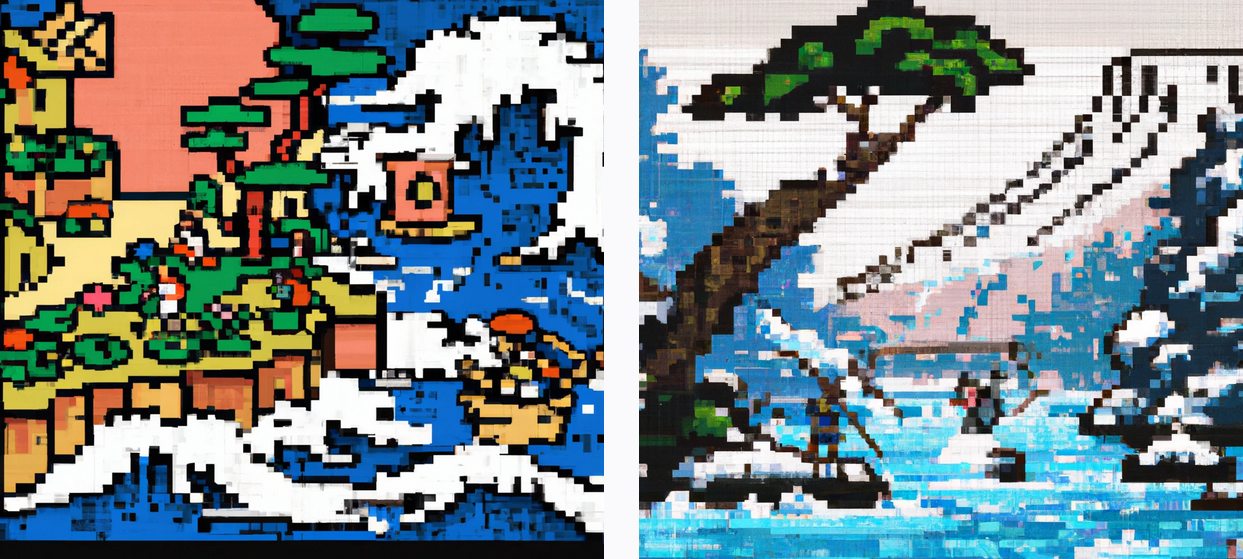

“Even the creators of DALL‑E 2 don’t know what the tool knows and doesn’t know. Instead, users have to work out what it’s capable of doing and how to get it to do what they want.” And indeed, that’s the part of the fun. DALL-E’s own interface recommends that you “start with a detailed description,” and with a little experimentation you’ll discover that specificity is key. The renderings of “an eight-bit Nintendo game designed by Hiroshige” and “a cyberpunk downtown Los Angeles scene painted by Rembrandt” strike me as credible enough for a first effort, but adding just a few more words opens up entirely new realms of surprise and incongruity.

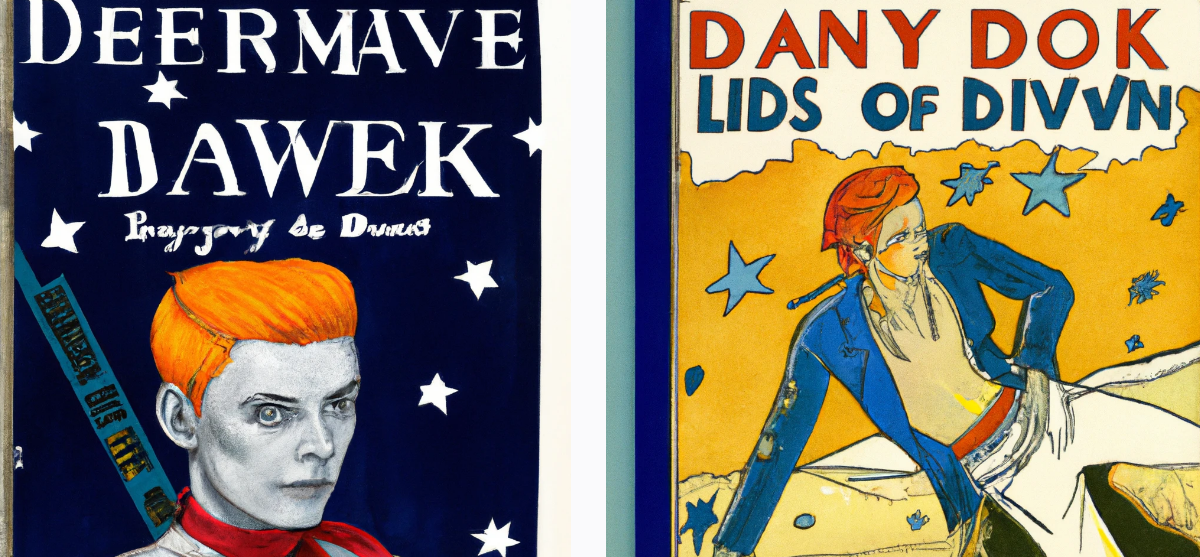

Just above, we have two of DALL-E’s infinitely many possible attempts to visualize “the cover of an old Ernest Hemingway pulp novel about the adventures of David Bowie.” Though the designs look entirely plausible, the titles highlight the technology’s already-notorious inability to come up with intelligible text. Other limitations of the newly public DALL‑E, according to Ars Technica’s Benj Edwards, include the requirement to provide your phone number and other information in order to sign up, the ownership of the generated images by OpenAI, and the necessity to purchase “credits” to generate more images after you’ve run through your initial free 50. Still, there’s nothing quite like typing in a few words and summoning up works of art no one has ever seen before to make you feel like you’re living in the twenty-first century. You can sign up here.

Related content:

Discover DALL‑E, the Artificial Intelligence Artist That Lets You Create Surreal Artwork

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.