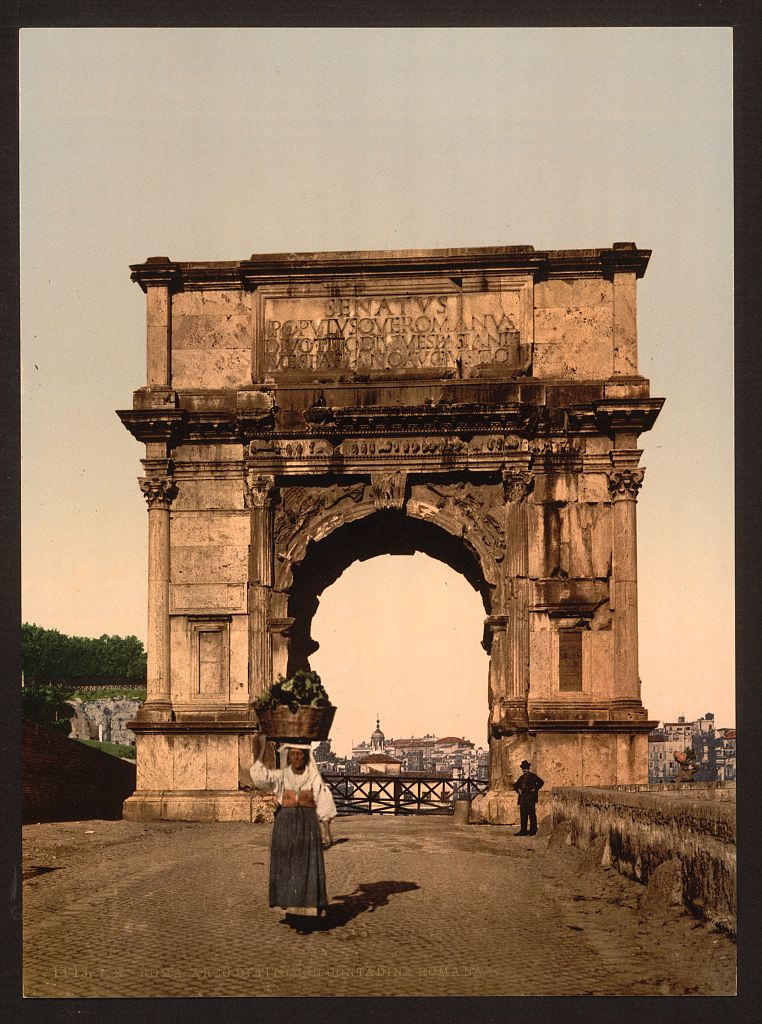

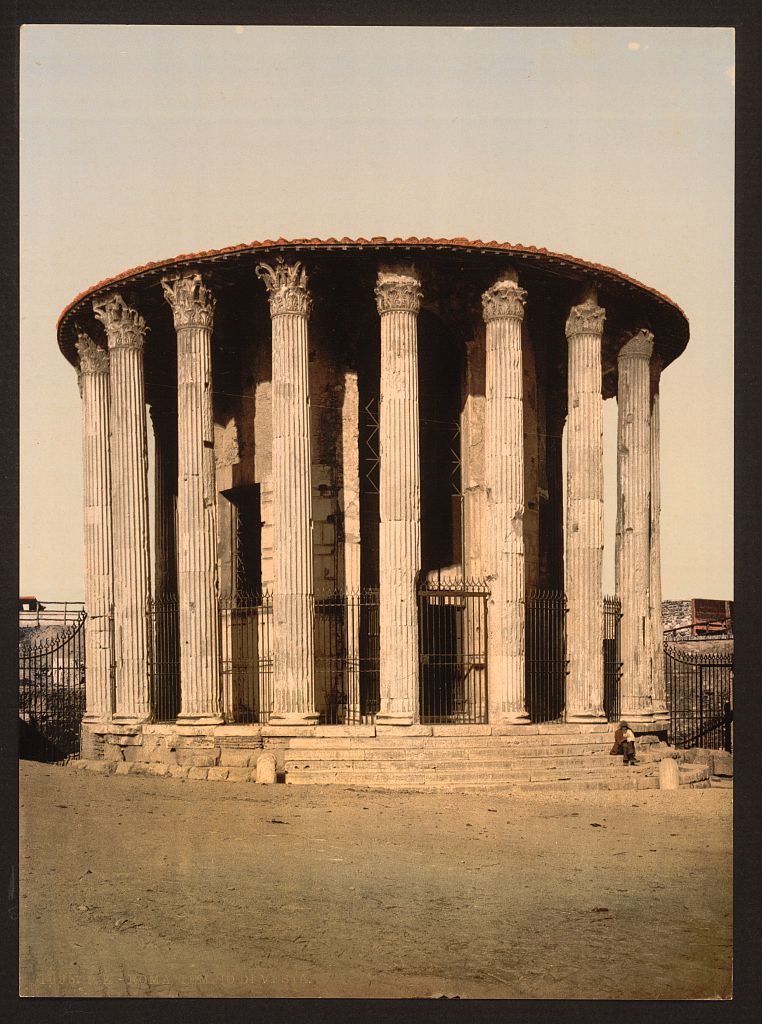

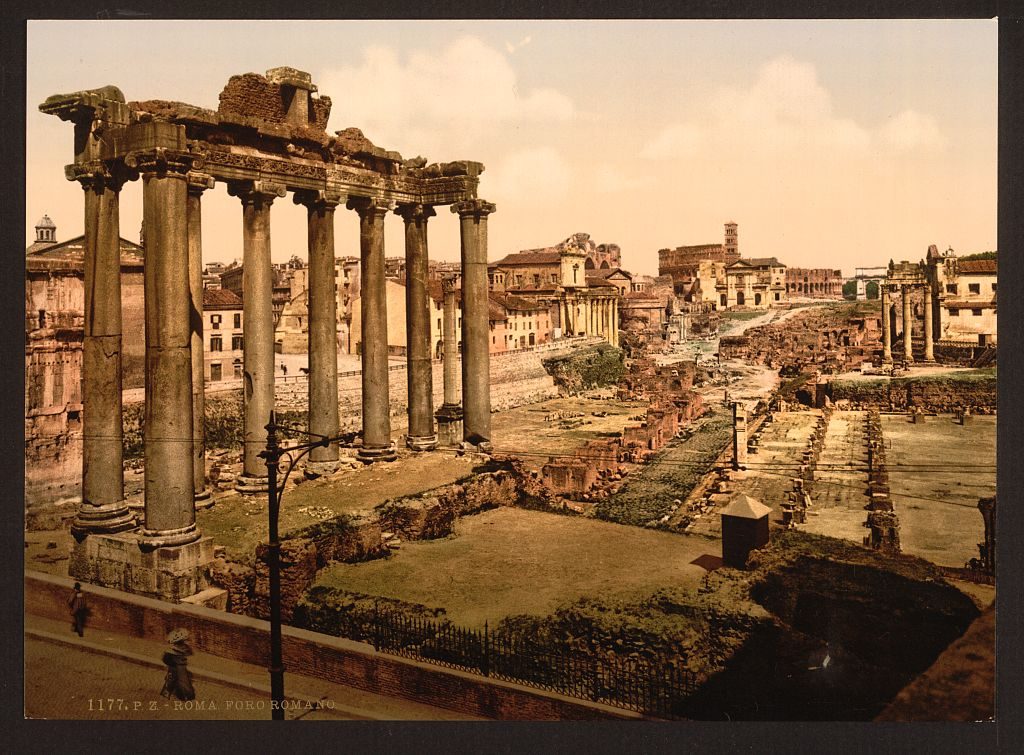

The idea of the classical period—the time of ancient Greece and Rome—as an elegantly unified collection of superior aesthetic and philosophical cultural traits has its own history, one that comes in large part from the era of the Neoclassical. The rediscovery of antiquity took some time to reach the pitch it would during the 18th century, when references to Greek and Latin rhetoric, architecture, and sculpture were inescapable. But from the Renaissance onward, the classical achieved the status of cultural dogma.

One tenet of classical idealism is the idea that Roman and Greek statuary embodied an ideal of pure whiteness—a misconception modern sculptors perpetuated for hundreds of years by making busts and statues in polished white marble. But the truth is that both Greek statues and their Roman counterparts—as you’ll learn in the Vox video above—were originally brightly painted in riotous color.

This includes the 1st century A.D. Augustus of Prima Porta, the famous figure of the Emperor standing triumphantly with one hand raised. Rather than left as blank white marble, the statue would have had bronzed skin, brown hair, and a fire-engine red toga. “Ancient Greece and Rome were really colorful,” we learn. So how did everyone come to believe otherwise?

It’s partly an honest mistake. After the fall of Rome, ancient sculptures were buried or left out in the open air for hundreds of years. By the time the Renaissance began in the 1300s, their paint had faded away. As a result, the artists unearthing, and copying ancient art didn’t realize how colorful it was supposed to be.

But white marble couldn’t have become the norm without some willful ignorance. Even though there was a bunch of evidence that ancient sculpture was painted, artists, art historians and the general public chose to disregard it. Western culture seemed to collectively accept that white marble was simply prettier.

White statuary symbolized a classical ideal that “depends highly on the greatest possible decontextualization,” writes James I. Porter, professor of Rhetoric and Classics at the University of California, Berkeley. “Only so can the values it cherishes be isolated: simplicity, tranquility, balanced proportions, restraint, purity of form… all of these are features that underscore the timeless quality of the highest possible expression of art, like a breath held indefinitely.” These ideals became inseparable from the development of racial theory.

Learning to see the past as it was requires us to put aside historically acquired blinders. This can be exceedingly difficult when our ideas about the past come from hundreds of years of inherited tradition, from every period of art history since the time of Michelangelo. But we must acknowledge this tradition as fabricated. Influential art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann, for example, extolled the value of classical sculpture because, in his opinion, “the whiter the body is, the more beautiful it is.”

Winckelmann also, Vox notes, “went out of his way to ignore obvious evidence of colored marble, and there was a lot of it.” He dismissed frescoes of colored statuary found in Pompeii and judged one painted sculpture discovered there as “too primitive” to have been made by ancient Romans. “Evidence wasn’t just ignored, some of it may have been destroyed” to enforce an ideal of whiteness. While many statues were denuded by the elements over hundreds of years, the first archaeologists to discover the Augustus of Prima Porta in the 1860s described its color scheme in detail.

Critiques of classical idealism don’t originate in a politically correct present. As Porter shows at length in his article “What Is ‘Classical’ About Classical Antiquity?,” they date back at least to 19th century philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach, who called Winckelmann’s ideas about Roman statues “an empty figment of the imagination.” But these ideas are “for the most part taken for granted rather than questioned,” Porter argues, “or else clung to for fear of losing a powerful cachet that, even in the beleaguered present, continues to translate into cultural prestige, authority, elitist satisfactions, and economic power.”

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2019.

Related Content:

Why Most Ancient Civilizations Had No Word for the Color Blue

Why Ancient Romans Paid a Fortune for the Color Purple — More Than Even Silver

Watch Art on Ancient Greek Vases Come to Life with 21st Century Animation

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC.