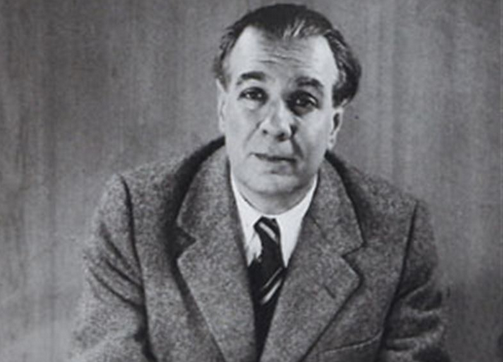

Image by Grete Stern, via Wikimedia Commons

I will admit it: I’m one of those oft-maligned non-sports people who becomes a football (okay, soccer) enthusiast every four years, seduced by the colorful pageantry, cosmopolitan air, nostalgia for a game I played as a kid, and an embarrassingly sentimental pride in my home country’s team. I don’t lose all my critical faculties, but I can’t help but love the World Cup even while recognizing the corruption, deepening poverty and exploitation, and host of other serious sociopolitical issues surrounding it. And as an American, it’s simply much easier to put some distance between the sport itself and the jingoistic bigotry and violence—“sentimental hooliganism,” to use Franklin Foer’s phrase—that very often attend the game in various parts of the world.

In Argentina, as in many soccer-mad countries with deep social divides, gang violence is a routine part of futbol, part of what Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges termed a horrible “idea of supremacy.” Borges found it impossible to separate the fan culture from the game itself, once declaring, “soccer is popular because stupidity is popular.” As Shaj Mathew writes in The New Republic, the author associated the mass mania of soccer fandom with the mass fervor of fascism or dogmatic nationalism. “Nationalism,” he wrote, “only allows for affirmations, and every doctrine that discards doubt, negation, is a form of fanaticism and stupidity.” As Mathews points out, national soccer teams and stars do often become the tools of authoritarian regimes that “take advantage of the bond that fans share with their national teams to drum up popular support [….] This is what Borges feared—and resented—about the sport.”

There is certainly a sense in which Borges’ hatred of soccer is also indicative of his well-known cultural elitism (despite his romanticizing of lower-class gaucho life and the once-demimonde tango). Outside of the hugely expensive World Cup, the class dynamics of soccer fandom in most every country but the U.S. are fairly uncomplicated. New Republic editor Foer summed it up succinctly in How Soccer Explains the World: “In every other part of the world, soccer’s sociology varies little: it is the province of the working class.” (The inversion of this soccer class divide in the U.S., Foer writes, explains Americans’ disdain for the game in general and for elitist soccer dilettantes in particular, though those attitudes are rapidly changing). If Borges had been a North, rather than South, American, I imagine he would have had similar things to say about the NFL, NBA, NHL, or NASCAR.

Nonetheless, being Jorge Luis Borges, the writer did not simply lodge cranky complaints, however politically astute, about the game. He wrote a speculative story about it with his close friend and sometime writing partner Adolfo Bioy Casares. In “Esse Est Percipi” (“to be is to be perceived”), we learn that soccer has “ceased to be a sport and entered the realm of spectacle,” writes Mathews: “representation of sport has replaced actual sport.” The physical stadiums crumble, while the games are performed by “a single man in a booth or by actors in jerseys before the TV cameras.” An easily duped populace follows “nonexistent games on TV and the radio without questioning a thing.”

The story effectively illustrates Borges’ critique of soccer as an intrinsic part of a mass culture that, Mathews says, “leaves itself open to demagoguery and manipulation.” Borges’ own snobberies aside, his resolute suspicion of mass media spectacle and the coopting of popular culture by political forces seems to me still, as it was in his day, a healthy attitude. You can read the full story here, and an excellent critical essay on Borges’ political philosophy here. For those interested in exploring Franklin Foer’s book, see How Soccer Explains the World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalization.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2014.

Related Content:

Video: Bob Marley Plays a Soccer Match in Brazil, 1980

Jorge Luis Borges’ 1967–8 Norton Lectures On Poetry (And Everything Else Literary)

Jorge Luis Borges Draws a Self-Portrait After Going Blind

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness